Editor’s note: The following comprises Chapter 5 of Children of Yesterday, by Jan Valtin (published 1946).

(Continued from Chapter 4: Banzai Night)

_______________________________________________________

It was a situation in which anything could happen….

(from the Division Record)

_______________________________________________________

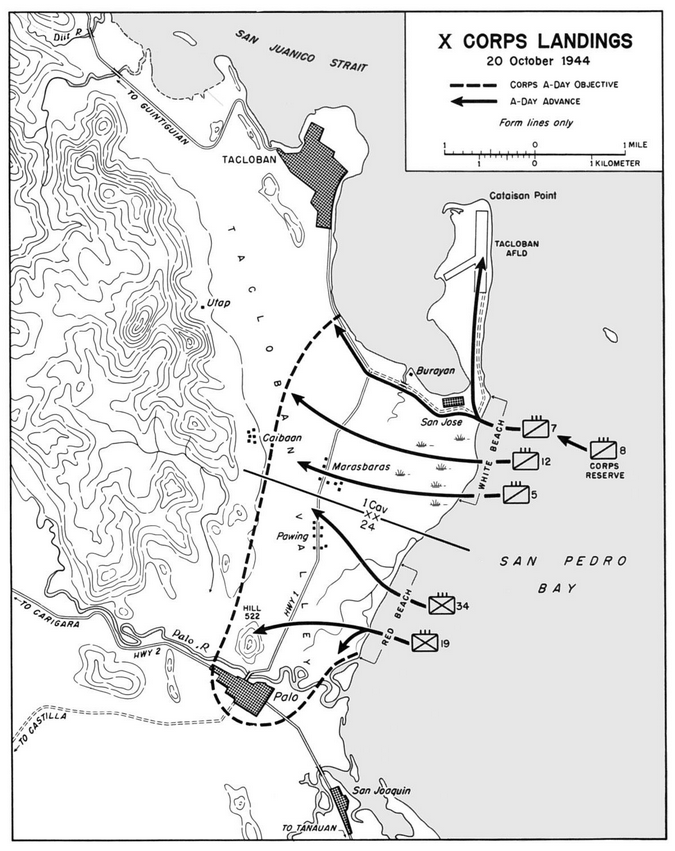

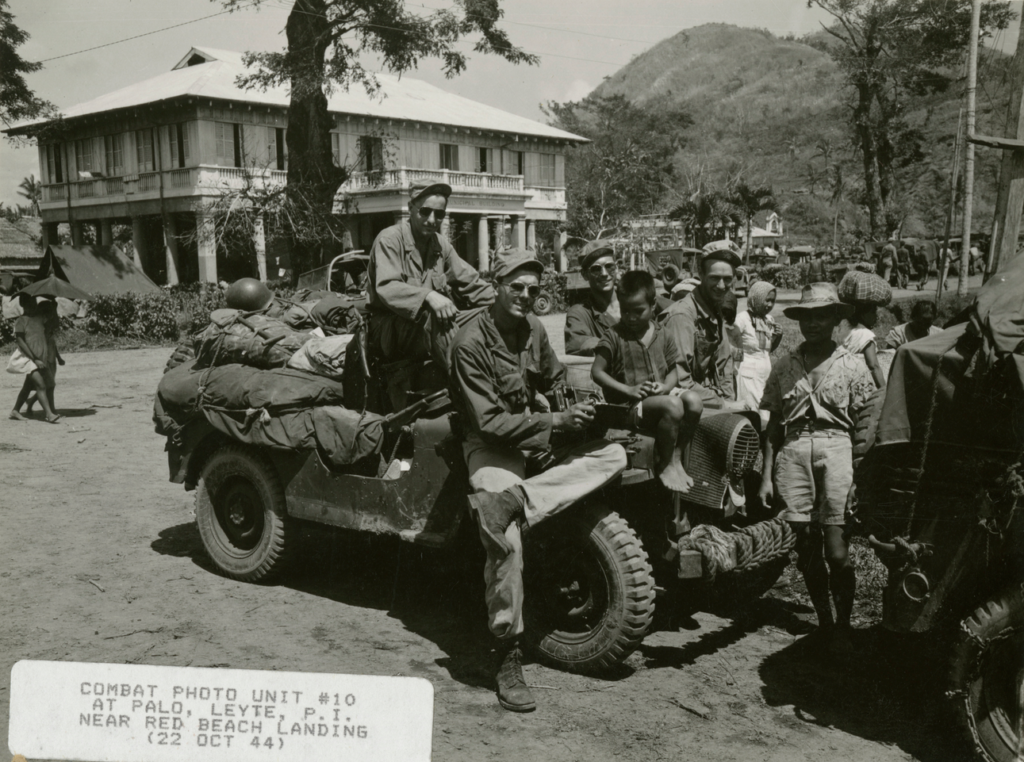

The push into the town of Palo was easy enough. The Nineteenth Infantry Regiment’s Second Battalion left the beachhead in battle formation shortly after daylight. It entered Palo at 3 p.m. and hardly a shot was fired. Infantrymen who had fought all through the previous day and all through the night relaxed. The entrance into lush Leyte Valley, seizure of which would cut the island in two, seemed wide open. That was on October 21.

But before dawn of October 26 all vials of wrath were poured about the vast old Spanish church of Palo. Palo River ran red with American blood. An ammunition dump burned and an American machine gun manned by Japs went berserk in the churchyard. Hostile demolition parties pierced the beachhead and forced artillerymen to close-quarter fighting. A wounded colonel made the church serve as prison and refuge for thousands; a baby was born under sniper fire; and the Division’s finance office “hit the dirt” when a pay clerk counting money saw the man at the next table fall from a rifle shot.[1]

Intelligence Sergeant Ernest Martin of Terre Haute was hunt ing on a map for the village of Alangalang. There was a sudden twang and the sergeant dived for cover. When he got up to retrieve his map he found a bullet puncture alongside elusive Alangalang.

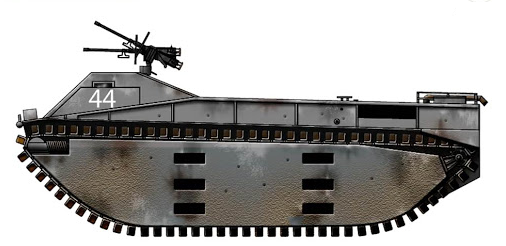

Leading a patrol on the outskirts of Palo was Sergeant Sam Needham, also of Terre Haute. He saw a smashed amphibious tank tilted on the bank of the road. “A mine did that,” Needham muttered. He switched his attention to the terrain ahead. However, the disabled “Alligator” opened fire on the American patrol. Needham approached the wrecked vehicle at a cautious crawl. A bullet hit him in the leg. By now he was too angry to give up. He maneuvered his patrol until the “Alligator” was surrounded. Then he dispatched a man for a bazooka. And when the weapon was brought to him, he sent a rocket crashing into the tank. Inside it, battered and silent, lay two Japs.

At the same time, on the beachhead, Lieutenant Coleman Freeman of Baltimore, an intelligence officer, received word that an enemy suicide squad was about to charge the nearby artillery command post. He grabbed a field telephone to speed a warning. But suddenly the artillery colonel heard a gasp at the other end of the line. There was the clatter of a falling telephone and the thud of a falling body. “Out,” thought the colonel. An instant later, he heard the lieutenant say evenly, “Pardon the interruption, Colonel— somebody just shot me through the ass.”

While one assault force pushed into Palo, other elements of the Division fought on three separate fronts. Colonel Zierath’s men on Hill 522 battled the enemy in a maze of dugouts and tunnels. Another taskforce tackled the roadblock astride the beach road to Palo. Battalions of the Thirty-Fourth fought tooth and nail for the possession of ridges flanking the coastal flats. The landscape separating these four spearheads was alive with Japanese. After the passage of the combat teams the enemy closed in again like water closing in the wake of a passing ship. A welter of clouds towered over distant summits, heralding rain.

Bypassing heavy concrete fortifications, the Palo attack force moved through sporadic sniper fire and reached the junction of the Palo-Tacloban highway with the fiercely contested beach road. The latter was no more than a muddy track, earmarked to become the main artery for the flow of Division supplies from Red Beach. At this point abrupt Jap mortar fire killed and wounded several men. Among the killed was the battalion’s sergeant-major. “Let’s go!” The assault force crossed the area of mortar bursts at a run.

A hostile strongpoint whose fire threatened to hold up the advance was liquidated by an Army mail clerk and his friend. With nothing more than a rifle and a submachine gun, the two volunteers crossed a soggy field exposed to the aimed fire of the Japs. They climbed atop the noisome emplacement and silenced it with a pointblank volley through its ports. The mail clerk was Angelo F. Derago of Camden, New Jersey.

A minute later scouts spotted a Japanese column moving down the highway from the direction of the beachhead. The detachment was a remnant of the enemy force which had killed Harold Moon during the small hours of morning.

The battalion halted and crouched low. Scouts prepared a hasty ambush. Machine gun fire raked the Jap column and the survivors sprinted for the shelter of a coconut grove. By radio the battalion commander requested Division artillery to pour shells into the grove. An ammunition truck speeding along the highway suddenly slammed on its brakes. Out of his cab leaned the helmeted driver, shouting,

“Goddam, I hate running over dead Nips.”

In open column to both sides of the highway, the task force resumed its march on Palo. The marchers eyed the flanking swamps and rice fields with suspicious disbelief. Makeshift mines studded the shoulders of the highway— wooden boxes filled with picric acid and armed with cocked grenades. The day was sultry and the men’s fatigues were black from perspiration. Rising to their right was the massive bulk of Hill 522. Without warning artillery shells fell among the marching column. American shells, fired in error. One man was killed, another wounded.

“Let’s get the hell out of here!”

The infantrymen quickened their pace. They rounded a bend in the road and ahead of them lay the bridge across the Palo River. Beyond the bridge the spire of the church stood outlined against a wall of clouds. Motionless, a man’s figure stood in an aperture of the bell tower. This watcher’s arms were outstretched like the arms of a man nailed to a cross. Fieldglasses showed that he was a white-haired Filipino.

The scouts peered at the bridge. They scanned the rows of nipa huts on the river’s far side. There was no sound, nor any sign of movement.

Was the bridge mined? The thickets along the river bank had all the requisites of a first-class trap. Did foul play skulk in yonder church and houses? The forward scouts crossed the bridge gingerly. The point followed. Nothing happened.

“Double time!”

The battalion double-timed across the bridge. It entered Palo without encountering opposition. The lone figure in the aperture of the bell tower had vanished. And then the sonorous voices of the bells rang out across the town.

The populace poured into the streets in a great welcoming surge. Ragged, dirty as they were from an almost three-year famine of clothing and soap, they danced and wept and shouted with jubilation. Even those who had lost members of their families in the fighting and bombardments of the past two days went wild with joy. Around the town square girls and women looted the hibiscus bushes of their flowers. Others came at a run, bearing palm wine in bamboo log containers. A happy crowd hoisted Lieutenant Joseph Maloy (who was later killed in action) to their shoulders and carried the grinning Yank in triumph through Palo. Children blurted what welcoming English they knew. Women screamed and laughed beneath the stone walls of the church. Riflemen, hunting for hidden Japs, took leave to measure the trimness of smiling girls. A skinny, barefooted priest clad in shorts dashed through the streets, exulting, “The bells, the bells, they are ringing again.”

From a corner of the churchyard Lieutenant Colonel R. B. Spragins of Evanston, Illinois, the battalion commander, surveyed the riotous scene. He did not like it. He knew the Japs too well. What would happen to these masses of celebrating people, the colonel reasoned, if the enemy should elect to launch a Banzai charge into the streets of Palo?

Spragins sent runners to summon the mayor and the priests of the town. “Gentlemen,” he told them, “there will be fighting in Palo. Your church has thick walls. I must ask you to lead your people into the church and to keep them there.”

Again the bells of Palo tolled. The priests herded their flocks into the church to offer thanks for their town’s liberation. All went, except the white-haired sexton and guerillas armed with captured Japanese rifles. Guards were mounted and the population of Palo pitched camp in the church.

Meanwhile the companies fanned out. At the edge of town, where a highway runs west toward Santa Fe and into the broad Leyte Valley, they struck stinging resistance. The Japanese were solidly entrenched under an agglomeration of native dwellings. Their mortars, machine guns and rifles ended any further exploration for that day. Scouts reported a massing of Jap assault troops on the spread-out battalion’s left; and dusk reached over the mountains of Samar. Spragins ordered a withdrawal from the outskirts of the town. The Division Record tersely reports that “A tight perimeter was set up for the night around the Palo church square, and it proved a most prescient move.”

While the tempest brewed over Palo, the Third Battalion of the Nineteenth Infantry Regiment set out to reduce the formidable roadblock at a bend of the beach road to Palo. Enemy control of this road made impossible the passage of supply convoys to the isolated forward elements of the Division.

This roadblock was a powerful and self-contained position; a series of concrete forts heavily reinforced with logs and earth. The whole was cleverly camouflaged. Connecting these strongpoints was a network of interlacing trenches, snipers’ holes and machine gun emplacements. Naval gunfire and aerial rocket shells had done their work. But advancing tanks had been stopped by a fantastic tangle of jungle brush and ditches. It was a job for infantry.

The battalion attacked in the brooding heat of early afternoon. All infantry weapons came into play, from tank-destroyers, flame throwers, and bazookas to the silent bayonet. In bitter encounters the infantry captured a 75-millimeter gun position, anti-tank emplacements and a hornets’ nest of heavy machine guns. But at the rim of a clearing, two hundred yards from the road bend, they were stopped cold. Infantry weapons were not enough to break that wall of fire. The assault teams dug in.

The riflemen cursed the day and the heat. They cursed the prospect of spending the night under the noses of Japanese bunkers. In single file a platoon of tank-destroyers ground through dense thickets. Corporal Irving Duane of Sacramento, California, was in the lead of the lumbering column. He was first to reach the rim of the clearing.

Retreat was impossible. Duane rolled his armored mount into the clearing where the field of fire was good. Through mirror sights he watched his shells pound into the enemy position. One of the guns fell silent. Other Jap guns belched flames through their disguise. Duane fixed their position in his memory. Then his periscope was shot out and he saw nothing. The blinded tank-destroyer’s steel hide rang under a tattoo of bullets.

Duane maneuvered his mount into a bamboo thicket. He jumped out and borrowed a periscope from a rearward machine. Soon he was ready again for action. He led the other tank- destroyers into the clearing. His fire pointed out to them a cluster of hidden enemy nests. Before the destroyer men called it a day they had destroyed five gun emplacements and killed most of their crews. Survivors were seen fleeing through the kunai.

From then on the defenders of the roadblock were given no rest. Batteries of heavy mortars were packed forward at dusk. All through the night to October 22 they lobbed demolition shells onto the Jap fortifications. Ammunition carriers worked their hearts to pieces.

At sunrise the men of the Nineteenth Infantry fixed bayonets and stormed. Their assault overran the strongpoints. Two hundred and seventy-six killed enemies were counted. Sergeant Emanuel Weixelman of St. George, Kansas, led the bayonet charge.

On the heels of the infantry the Division’s Combat Engineers moved in to clear the beach road. Debris, mines, traps, log barricades and corpses were pushed out of the way. And soon the first supply convoy rolled inland in the wake of an armored bulldozer.

In the supply train was an amphibious tank manned by Rade Allen and “Andy” Sapp. Allen came from Ft. Worth, Sapp from Belleville, Illinois. As they crossed the Palo-Tacloban highway, an infantry officer jumped from a thicket and waved them to a halt. Would the “Alligator” be willing to rescue some wounded soldiers up front before they would be killed by the Japs?

“Sure,” said Sapp and Allen.

The wounded men, they were told, lay in an area covered by enemy fire. To get to the spot, the amphibious tank would have to travel more than a thousand yards along the Palo highway. Enemy troops still infested marshes to both sides of the road. Rade Allen and Andy Sapp looked at each other.

Their machine clambered to the highway. The Japs did their utmost to stop it. For a thousand yards the “Alligator” lumbered down the road as fast as its tracks would move, its gun spouting fire forward and right and left, “strafing ditches, native houses and machine gun positions parallel to the highway, killing untold numbers of the enemy and demoralizing more.”[2]

All went well until a lone Japanese leaped from a ditch and hurled a mine under the vehicle’s track. The tractor stopped.

In the wrecked “Alligator’s” belly the men were dazed from the explosion. Again Sapp and Allen looked at one another, and each saw that the other was wounded. They tried the engines. The tractor was dead. Through the narrow sight slots they saw the Japs close in. They tried the gun. It worked.

Three hundred yards away Lieutenant Haskel P. Miller of Wichita, Kansas, saw an amphibious tank blasted by a mine on the Palo road. He also saw a swarm of Japanese circling like wolves around an elk at bay.

Miller, leader of a machine gun platoon, acted speedily. First he directed the fire of his guns upon the Japs nearest to the crippled machine. Then he organized a party of ten men in a sortie to reach the beleaguered tractor. But sudden machine gun fire forced him to abandon the attempt.

He called for mortar fire to neutralize the Jap machine gun nest. He also called for another amphibious tank to rescue the still battling crew of its disabled brother. As the second “Alligator” clattered down the highway, the lieutenant’s machine guns protected its advance. The rescue became a success, and the road was cleared.

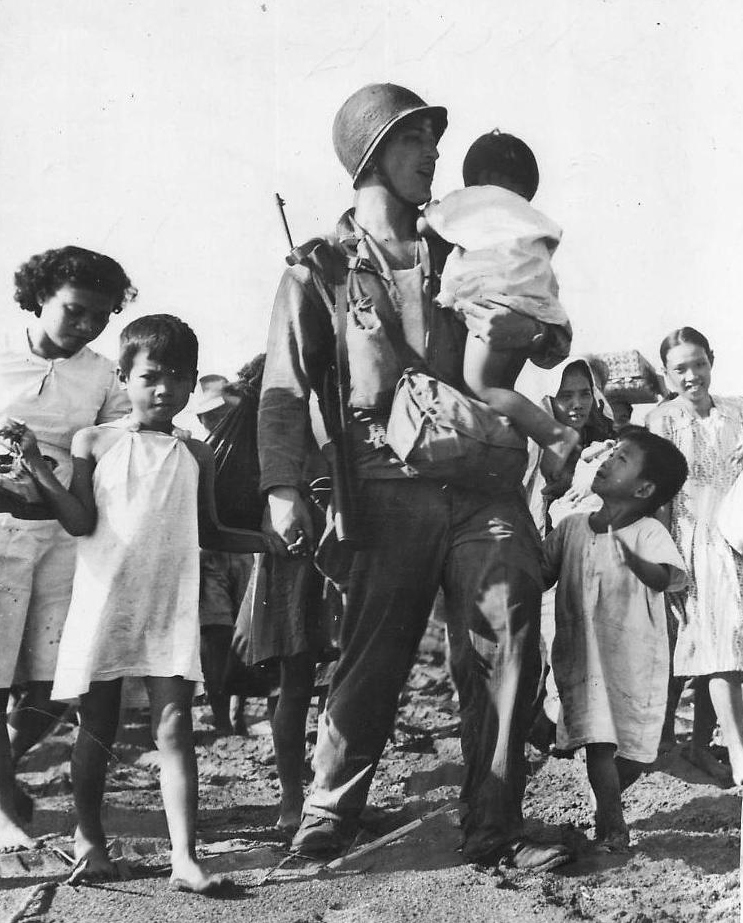

But soon another column was treading the restless highway to Palo. This time it was a ragged procession of thousands of brown men, women and children. Flanking it were silent Yanks who cleared the way by potting snipers as the caravan trod on.

On crowded Red Beach the new problem was created by the steady influx of civilian refugees. When the invasion began, the native populace had fled to the hills, away from bombs and naval cannonade. This migration was reversed as the fighting moved in land. Refuge on the still sniper-ridden beachhead seemed a smaller evil than existence among artillery barrages and mobs of exasperated Japanese.

The first civilians had begun to filter through the fighting lines onto the beachhead shortly after noon of the day of the invasion. On the morning of October 21 their number grew by leaps and bounds. They arrived in decrepit hordes, denizens of drowsing barrios suddenly overtaken by the juggernaut of war, led by a bare-legged patriarch. Many were ill with the afflictions of the tropics, with malaria, skin sores and wounds that had long refused to heal. Ever since the Japanese had come these people had been without medicines.

Most of the refugees carried all their possessions on their backs, or in bulging bundles atop their heads. Their expressions were a mixture of fear, fatalism and smiles. By nightfall there were thousands. A child was born on the beach in the shelter of a bulldozer blade— a husky boy.

To Colonel Alva C. Carpenter of Ft. Wayne, Indiana, the Division’s judge advocate, fell the task of caring for the charivari throng. He procured and distributed rations. He formed the men into labor gangs and set them to building an enclosure, to digging fresh water wells and latrines, and to burying the enemy dead in shallow common graves. He also set up an emergency dispensary to care for the sick. He corraled stray children and made efforts to locate their parents. He listened to countless anxious questions concerning wives, daughters, babies, and grandmothers lost in the melee of battle.

By October 22— the third day of the invasion— the crowds on the weirdly congested beach became so dense that any Japanese artillery or air attack would have resulted in hideous slaughter. Rumors were at large that Nippon’s navy had come out of hiding to fight, that battleships and cruisers had been seen prowling in the Sibuyan and Sulu seas, that the Japs were steaming on in full force to blast the Americans off the Philippines. Colonel Carpenter decided to move the refugees off the beach and into Palo.

Squads of riflemen took the lead. Following them was an almost naked ten-year-old boy singing “God Bless America.” Then came the silent procession of the homeless. Nearly all were bare-footed. Many of the women wore camisoles made of coconut fiber. Others wore pieces of uniform they had found on the beach. One slender young woman was decked out in flashing Spanish finery, her other valuables balanced on her head, the hem of her flowing red silk skirt trailing about small and muddy ankles. Bundles of Army rations dangled from bobbing bamboo poles. Most of the men carried bolo knives in wooden sheaths tucked in the waistbands of their shorts.

Interspersed with men from the Division’s finance section, who acted as guides, the caravan trudged up the rutted beach road. As the head of the column passed the junction of this track with the Palo highway, Jap snipers opened fire. The threat of panic was quickly quelled. The refugees dispersed and huddled in the ditches. Flanking patrols destroyed the snipers.

Infantrymen had a hard time preventing natives from picking up Jap uniforms and equipment strewn along the highway. These baits had been wired, and the wires led to mines. The procession entered Palo and assembled under the statue of Christ on the town square where the mayor relayed instructions. Young Filipino volunteers were sent off to spy behind enemy lines. All others were locked into the church. The gnarled sexton ascended the tower and again the bells rang over Palo.

Around the tight churchyard perimeter the men were tense. There was continuous sniping in the streets and alleys of Palo during the early part of the night to October 22. The purpose of this harassing fire was to keep the Americans from resting; to have them drowsy with fatigue when the hour of the night surprise assault would be at hand.

On the verandah of the stone-and-tile municipal building stood Colonel Spragins. With him was Captain Bridgforth, of Yazoo City, Mississippi; short, slim, a hundredweight of human dynamite. On the wall behind them hung tattered Japanese posters announcing a “victory” dance to be held on the Palo town square that very night. It was 11 p.m. The sky was covered with clouds. The night was sultry and pitch black. Over the radio Bridgforth called the Thirteenth Field Artillery Battalion on the beach. He asked for artillery fire on all principal roads leading into town. Three hundred and fifty shells pounded the roads to Santa Fe and San Joaquin in the course of the night, blocking their use to enemy reinforcements.

Exactly at midnight the earth trembled from the blast of a major explosion. A pillar of flames mushroomed over the west section of Palo. Someone— Jap or guerilla— had set fire to a house full of Japanese ammunition. A flood of prancing glows and weaving shadows filled the outlying streets. The waiting men on the perimeter were content. The blaze cast bizarre yet helpful light into the irregular complex of buildings facing the battalion’s outposts. Hours passed and nothing happened.

The enemy struck at 0330. He carried machine guns in his most forward echelons. He also carried mortars, grenades, mines and fixed bayonets. His assault groups moved boldly toward the church of Palo. At a rapid pace the Japanese advanced along the streets, hugging the decrepit houses, rushing through alleys and back yards, silent, still holding their fire.

From the shelter of their shallow foxholes Louis Diaz of Amarillo, Texas, and his two companions saw them come. There was a group of five, very close, lunging out of a clump of banana trees. Diaz fired. The Japanese returned the fire as they rushed. Between shots from the hip they tossed grenades. One of Diaz’ companions was killed. He died swiftly. The other was seriously wounded. Three of the attackers had fallen.

Diaz pushed aside the body of his comrade and stood upright in the foxhole. In the reddish glow of the burning ammunition dump he saw two remaining Japs pounce forward. Diaz squeezed the trigger in lightning succession. The yelling became a gurgle and a sob. The Japs tumbled. They kicked wildly at the edge of the foxhole. Diaz fired until their kicking stopped.

The whole town was in an uproar. The battalion outposts met the raiders with a murderous volume of fire. At one corner of the church square two machine guns led by Sergeant Vernon Drake of Fletcher, North Carolina, sprayed bullets down streets where Japs swarmed like harpies on a rampage. The snarling shower of lead did not deflect the attackers from their purpose. They mounted mortars on an intersection two blocks distant. Soon the high explosive “pears” plummeted out of the night. Drake’s gunners were compelled to seek cover. The Japanese assault teams had vanished and Vernon Drake saw that the street ahead lay empty.

Somewhere in the row of native dwellings a dog barked. The barking turned into agonized yelps. Drake realized that the Japanese had darted into the buildings. They were making their way to the churchyard in house-to-house dashes. The clamor of a machine gun proved his guess correct. The nearest dwellings, less than thirty feet away, seethed with Japs.

Drake felt as if someone had struck him on the head with a hammer. A machine gun slug had found its mark. Dazed, and blinded by blood, he rallied his section. “Fire,” he shouted. “For Christ’s sake, fire.” Now his own machine guns roared, ripping into the houses across the dusty lane. Their muzzle blasts close to his head all but tore his ears away.

The Japanese attempted a headlong rush across the street. Drake’s crew threw them back. With morning, thirty-odd Japanese corpses lay within a radius of ten yards from Drake’s position.

Forward artillery observers working from the roofs and windows of buildings drew in the curtain of fire laid by the Division’s Field Artillery to within a hundred yards of the town square perimeter. This wrought havoc among concentrations of Japanese under orders to break the American hold on Palo; but the violence of the concussions jolted the battalion’s forward elements from their niches. In the vault-like gloom of the church the explosions reverberated like thunder rolling beneath the surface of the earth. Few slept, among the thousands. Bullets shattered the stained-glass windows. In the stench of cooped-up and fearful humanity children cried, a woman went insane, and another baby was born. Under the effigies of the saints couples mated, heedless of the storm. Their sighs mingled with the sounds of many mumbled prayers and the clatter of machine guns, and a priest’s somber voice read mass in the tomblike darkness.

A bare hundred yards from the church, a platoon of Japanese charged a machine gun manned by Jerry Lanik. Jerry’s fire drove one section of his assailants to the cover of a pile of boxes. From there they fired and flung grenades. Lanik knew that the boxes contained ammunition. Unable to reach the enemy, he poured tracer bullets into the pile until the whole thing erupted into flames. With a cloud of debris Jap heads, arms and legs were hurtled into the brilliantly illuminated night. Then Lanik doubled up under the impact of a sniper’s bullet.

The house under which his machine gun was mounted caught fire. The flames threatened to engulf Jerry Lanik. Scorched and wounded he fought on until a Jap sprang from a window and threw a grenade. Lanik was mortally wounded.

Nearby lay Private James B. Bagley, the assistant gunner. He, too, had been wounded by rifle fire and grenades. At home, in Kokomo, Indiana, his wife Rosalie prayed for his return. Amid devastation, fire and death he remained with his gun. About him the remnants of the Jap platoon darted like frenzied gnomes. Bagley fired until he became too weak from loss of blood to manage the machine gun’s mechanism. He crawled a little way off and continued to defend his gun with his rifle.

The night fracas for Palo lasted through almost four hours. One repulse did not daunt the suicidal obsession of the attackers. Three times they rushed the town from the south and west, and one Banzai assault struck from the direction of the beachhead against the Palo River bridge. Japs popped in and out of houses fronting the church. They swirled in shouting eddies about the courthouse which served as a hospital for the many wounded. From a window Colonel Spragins directed the battle. In the glow of fires and the flashes of bursting mortar shells his unruffled presence and his close-cropped mustache remained a reassuring landmark. He disappeared from the window when shrapnel slashed his forehead. But minutes later, bandaged, he was back again on the job.

Somewhere in the square below the colonel a B.A.R. gunner emptied magazine after magazine into the Japanese onslaught. And suddenly the gunner’s automatic rifle jammed. The men of his squad were falling back. A burly Jap came in, lunging in the van of the attackers, howling “Banzai,” a saber in one fist, a grenade in the other.

The gunner slipped his hands down the barrel of his jammed automatic rifle. He, too, was howling, for the red-hot barrel of the weapon badly seared his hands. All the same, he rushed out of the perimeter and pounded the howling Jap to death. This was the high-water mark of the attack.

This gunner’s name?— Private First Class Jesse W. Martin of Dunbar, Kentucky.

The streets of Palo seemed peaceful enough during the hours of daylight, not counting occasional snipers. More refugees arrived. There were now more than five thousand crammed into the church. On street corners and in the shelter of trucks soldiers sat, digging food from ration cans, their rifles within reach and ready for instant action. Others, not on guard or on patrol, stripped in abandoned houses and doused themselves with helmets full of water. Still others slept in and under vehicles, in doorways and backyards, and in the shade of banana and hibiscus.

In the church square a dumpy guerilla counted a fistful of Japanese ears. Aid men made the rounds, distributing atabrine and tablets for the purification of water used for drinking. The wounded were evacuated to the beach. Around a broken water main Filipino women squatted, washing uniforms in exchange for soap. Gangs of native laborers were put to work, clearing away the debris of battle and burying the dead. From the streets and alleys of Palo they collected more than one hundred Japanese corpses, and there was evidence that many others had been dragged away. Thin columns of smoke rose in the distance to the west, where the Japs cremated their salvaged dead.

(Funerals are the only religious ceremonies known to Jap soldiers in the field. They dig a large hole and fill it with kindling. They place their dead on this bed of kindling and heap more wood around them and on top of them. Then a Japanese officer makes a speech. He addresses the corpses as though they were still alive. He praises their courage and promotes them to a higher rank. When he is finished he bows to the killed. Soldiers soak the pyre with gasoline and then stand at attention, bayonets fixed. The officer throws a torch onto the pile of wood, and when the flames spring up each soldier silently files by and bows.)

Artillery growled in the surrounding hills. The dull crack of grenades punctuated the afternoon. An officer walking alone through the outskirts to meet a supply convoy rolling in from Red Beach spotted two Japs prowling by the roadside. They had cut through the trunk of a large tree and they were about to stretch a wire from this tree to a point across the highway. Any truck colliding with this wire would cause the tree to fall. The officer whipped up his carbine. He shot one Jap, and the other surrendered. The American took no chances: he forced the captured Jap to strip, then marched him naked into Palo.

Night fell.

When the Division’s 52nd Field Artillery Battalion moved into Palo and set up its guns, its men thought that they had come unobserved by the foe. But suddenly a shell burst to their immediate front, another to their rear. They knew then that an enemy observer could not be far away. “Bracketing” the cannoneers’ positions with one short and one long round was his method of marking the spot for the benefit of Jap gunners. As a result the artillery battalion did not fire that night, but moved away under cover of darkness.

A half hour before midnight Sergeant Charles Taylor of Desha, Arkansas, in charge of a tank-destroyer, saw a squad of Japanese dart across a road into the shelter of a group of bamboo huts. Somehow this enemy team had managed to filter through the outer defenses. The sergeant waited. Soon he heard the Japs emerge from the shacks. He saw them advance in a low- crouched run. Some carried bulky bundles on their backs. Their job was demolition.

Taylor opened fire with a submachine gun. Two of the marauders fell, the rest scattered. But soon snipers’ bullets whined past him, and other Japs who had wriggled in under cover of an adjacent first aid station lobbed grenades. The sergeant ducked the fragments. Presently a lone Jap dashed toward the self-propelled gun. This enemy carried something that looked like a heavy box.

There were three tons of ammunition and one hundred and eighty gallons of gasoline aboard the tank-destroyer. The Arkansan rushed to protect his weapon. He overtook the Jap less than three feet from his cannon and killed him. The box, he found, contained dynamite fused with a hand grenade.

A number of native huts were then burned down to open lanes of fire and to deprive the enemy of concealment. Although the Filipino populace was kept secure in the church, packed there as tight as herrings in a barrel, refugees continued to stream into town, and there was no way of stopping them. But two figures in women’s clothes dodging past guards at the Palo River bridge turned out to be Japanese soldiers; both were shot to death. An enemy bombing raid set an ammunition dump ablaze. Rain fell in intermittent showers and soon became a steady torrent. Four days went by before the town and its link to Red Beach could be completely secured.

On a dark, wet night Private Charles Scott of Marengo, Iowa, on guard near the center of the beach perimeter, heard a steady tapping sound in a nearby palm grove. To the right of him was a field hospital, to his left the kitchen of the 13th Field Artillery. The strange tapping continued. The soldier investigated. He found a lone figure beating a palm trunk with a stick.

“Hey!” shouted the guard. “Crazy?”

The murky figure continued its tapping. Against an opening in the foliage the soldier saw the outline of a Japanese helmet. He raised his rifle and fired. The Jap fell.

Then all was quiet again.

Rifles cracked at 0130. An infiltration party had broken into the kitchen and hospital area. Their tree-tapping comrade’s job had been to reveal the location of the guards. A cannoneer asleep in a trailer was killed. Another American groping his way through darkness and confusion met sudden death. Several wounded men in the field hospital were hit by Jap bullets. The raiders then leaped on a truck parked near the kitchen tent and ran amuck in the dark. Mounted on the truck was a heavy American machine gun. For an hour the Japs sprayed the artillery bivouac with American bullets. From all sides the surprised artillerymen returned the fire with pistols and carbines. Little could be seen in the pitch-blackness except a chaos of red muzzle flashes. Aid man Angelo Volpe, a native of Australia, crossed and re-crossed the firing zone on hands and knees, helping the wounded. Finally the machine gun jammed. The raiders dispersed and vanished in the swamps. Five dead Japanese were found at dawn, their eyes staring blind into the rain. In the artillery kitchen the cooks found every pot and pan riddled by bullets. And an officer commented drily that henceforth the cannoneers should fix bayonets on their cannon.

The finale of Nippon’s farewell to Palo came in a bold and wily thrust.

Colonel Spragins’ battalion had been relieved by the Third Battalion of the Nineteenth Regiment in the occupation and defense of Palo. “King” Company’s riflemen had pushed southward two miles to San Joaquin.[3]

There they had encountered wicked resistance from concrete strongpoints, anti-tank cannon and log barricades; behind a cur tain of naval gunfire they had withdrawn to Palo. Sentinels were posted at approaches and intersections. Weary soldiers curled up to sleep along the church walls, beneath verandahs and on floors of abandoned shacks. For the first time in five days these men took off their boots. The password was “Lullaby.”[4]

Along trails winding through kunai grass and down brush- covered hillsides Japanese patrols lurked silently. Refugee families treading the dark trails in their endeavor to reach the security of American lines found themselves waylaid. Japs jumped from the undergrowth and halted the pilgrims. Women wailed and children whimpered.

“Keep quiet,” they were told. “Come with us.”

Here and there a man drew his bolo knife to defend his women. He was quickly bayoneted. Here and there a Filipino mother stepped forward intent on saving her daughter from hurt ‘Take me, Japanese, if you must.”

The Japs laughed.

“This way!” they said. “We kill you if you make one sound.”

At bayonet point the natives were herded downhill. They reached a jungle-clad gully. Many more natives were there. All around them, hovering in compact groups, were Japanese soldiers. The Japs sat in the darkness, their arms clasped around their knees and hugging their long-barreled rifles. At times there was the faint scraping of a helmet rim against a rifle barrel, and then there was a hiss demanding silence. Officers moving among the huddled groups whispered instructions. The sheaths of their sabers swished in the wet grass.

What did they whisper?

“We shall penetrate the town of Palo as a spear penetrates a stomach. We shall carry mines, grenades and demolition charges. We shall fire the buildings and the vehicles. We shall kill the guards and slice into the town square. We shall slice through the town until we come to the bridge. We shall blow this bridge to block the Americans’ supplies. Then we shall disperse. Each squad will seek to return on its own.”

Then a captain addressed the Filipinos cowering there in frightened clusters:

“We have good use for you. You shall be our advance guard and our shield. You shall lead us into Palo, a cushion against Yankee bullets.”

The captain in charge of the assault team was a swarthy man with short legs and powerful shoulders. His Samurai sword had a pearl-and-ivory handle and a sheath of delicately carved leather —fishes, flowers, and a geisha with a smile and a fan. He tapped his sword. It was the signal to proceed. Kicks and bayonets prodded the civilians into the lead.

At 3 a.m. the Division’s guards heard a mass of people approach them from the southwest. A flare swished toward the clouds, fleetingly illuminating the scene.

“Holy smoke,” a gunner muttered, “look at that.”

What he saw was a mass of unarmed people, men, women and children crowding the road, shoulder to shoulder. In the white glare of the flare their faces were like masks. Their arms hung limply and their feet lagged as if with great fatigue. Then the flare went out and it was darker than before.

Indistinct cries drifted through the night: ‘The Japanese have driven us away from San Joaquin.”

“Don’t shoot, please…. Filipinos.”

And a hoarse bark:

“Me guerilla…. Me guerilla.”

The guards held their fire. A thin shape detached itself from the steadily advancing crowd. It sprinted frenziedly toward the American outposts. The guards sent up another flare. They saw that the runner was a native boy, his face distorted with fear and exertion. His thin voice cried piercingly, “Shoot, shoot, Japs, Japs.”

Still the gunners held their fire. God damn it to hell, could they massacre a miserable lot of civilians? The native boy sprinted through the outpost line, shouting, “Shoot! Japs,” until he fell in an exhausted heap. Then it was too late. Like phantoms from a nether-world the Japanese broke through their mask. A squat, short-legged fellow in their van swung a Samurai sword. They killed all the guards except one. This lone survivor rushed through the town to alert the sleepers and the units stationed around the Palo River bridge.

Boldly the raiders broke into the town square. They overran a section of heavy machine guns in front of the courthouse. They captured an anti-tank cannon. They attached a mine to a tank-destroyer and blew it up. Two soldiers guarding a quartermaster supply dump were overpowered and killed. The raiders poured gasoline into the dump and set it ablaze. Men awaking from sleep were baffled by the absence of the familiar “Banzai” yelling.

The Japanese worked with a cold and ferocious efficiency.

They swept across the town toward the Palo River bridge, spreading havoc on the way. They mounted captured machine guns on captured trucks and sent sprays of bullets across the town square. A Jap squatting under the statue of Christ sent tracer bullets ripping into buildings from the muzzle of an American gun. An ammunition dump burst into flames, a loaded truck was burning, a jeep was blown to bits, a dozen other vehicles were mauled by flying lead. Japs surged around an emergency hospital full of wounded men. A squad of raiders armed with knives raced from truck to truck, slashing tires. Of twelve men guarding the approaches to the bridge all but three were killed or wounded. A drawn-out moan of despair arose from the crowded church. The bells of Palo rang as if in a storm of pain.

Gradually the defenders found their bearings. A platoon of engineers took charge of the far end of the bridge. Negro quartermasters, angered by their rude awakening and the burning of their trucks, reached for pistols and pitched in. Infantrymen stumbled from their resting places, half dressed and fighting mad. Lt. Col. George H. Chapman, the regimental commander, found his command post in the municipal building raked by machine gun fire. He stepped to a window and saw a bevy of Japs attacking twenty yards away. He summoned the headquarters clerks and messengers and linemen and transformed the building into a fortress. Firing from windows, the colonel and his crew accounted for twenty of the attackers.

Private Denoff, a quartermaster, awoke and smelled smoke. He soaked his blanket in a water bag, and ran to smother the fire. On the way he clubbed a Jap to death with his carbine. Wladyslaw Swarter of Wilmington, Delaware, protected Colonel Chapman who strode through the melee to investigate the situation at the bridge. A sniper made the colonel his target. Swarter saw a comrade shot at the river’s edge; rushing forward he saw a Jap leap up and vanish behind a wall. Heedless of other enemies nearby, Swarter hurdled the wall in pursuit of the sniper. The Jap suddenly stopped, faced his pursuer with a snarl. Swarter shot him through the head.

Sergeant George Nieman of Detroit, and Corporal Eugene Holdeness of Noxapater, Mississippi, were blinded with sweat while they defended their self-propelled howitzer against assaults which struck them simultaneously from several sides. Their weapon was mounted in front of a wooden building which served as an emergency hospital. Down the street some eighty Japanese attacked with grenades and fire from a captured American gun. As they approached in house-to-house dashes they hurled jugs filled with gasoline. Flames enveloped the howitzer and Sergeant Nieman was wounded. Forced to abandon their mount, the two Americans dodged into a muddy alley. “Look!” said Holdeness. The Japs were about to set the hospital afire. “Let’s go,” said Nieman.

They climbed into an adjoining house and reached the up stairs windows. Nieman carried a carbine, Holdeness a Tommy gun. The raiders saw them and broke into a weird howl. The rat-a-tat of machine gun slugs splintered the window frames. Holdeness and Nieman did not budge. Through the rippling of the Tommy gun sounded the quick crack of the carbine. The Japs gave it up as a bad job. They roved on down the street to ward the bridge, leaving eight of their comrades in a bloody tangle at the hospital threshold.

Home-bred initiative of individual Americans was the decisive factor in the repulse of this last foray into Palo. The monstrous intermingling of skirmishers allowed for no co-ordinated defense. You fought, and your comrade, making your own decisions, or you died. When an ammunition dump exploded fifty yards from his position, Artilleryman Charles Mott of Wichita, Kansas, rushed into the heat and carried a wounded comrade out of enemy reach. (The Japs gave wounded men the bayonet and a kick in the face, just to make sure.) Or take Corporal Nickerson of Mercer, Maine, another cannoneer. When the stores of ex plosives caught fire, he withdrew his section a hundred yards; but immediately after the explosion he rushed his men back into their old positions to meet the Jap onset.

Their toughest antagonist the Japs found in Frank Wisnieuski. They had scattered and pushed to the rear the riflemen assigned to protect an American machine gun emplacement. They had badly wounded the gunner, and the gunner had dragged himself to cover. There remained only Wisnieuski, the assistant gunner.

On they came, with light machine guns, rifles, grenades and bayonets, thirty against one. They were almost on top of him. Wisnieuski said later that he did not expect to come out of it alive. He stayed there and fired. Two grenades fell directly in front of his hole. A third grenade plopped inside.

Wisnieuski jumped out of his hole as the grenade exploded. He dived back into his hole, struggled to lighten his battered gun. Would the thing still fire? He did not know.

Above him, sinewy silhouettes against a gloomy sky, two enemies, bayonets down, plunged in for the kill. Wisnieuski pressed the trigger of his upset gun. It fired. His assailants tumbled like ripe fruit.

At dawn the lone gunner counted. There were twenty dead Japanese in front of his foxhole. A little way off, not far from the portals of the church, lay the body of a Jap captain. He had a swarthy face, short legs and powerful shoulders. Beneath him the ground was purplish-black. “The ugliest Nip I ever saw,” a passing soldier said, and spat.

In a room of the municipal building a young man stood up, stretched, yawned, then crawled under a table and fell asleep. He was the headquarters telephone operator. While the tattoo of machine gun slugs knocked plaster from walls and ceilings, Private Bill Malzahn of Flint, Michigan, had stayed at his switchboard. During the hours of the raid he had received eight requests for artillery support from other areas of the disconnected front.

So, peace came to Palo. Throngs emerged from the church. People blinked as though they had never before set eyes on their town. Soldiers leisurely searched the pockets of enemy killed for loot and there was the smell of fresh coffee mingling with the foul smell of death. Children begged for chewing gum and grown-ups for cigarettes. Here and there an intelligence man rummaged for documents. And a tawny policeman nailed up two signs which said,

“The Chief of Police of Palo wishes all People to know that the Police Station is not a Morgue. Cadavers are NOT to be deposited There”;

and,

“Ceiling Prices for G I Laundry:

Pants, 25 centavos

Shirts, 15 centavos

Socks, 5 centavos

Violators will be punished.”

(Continue to Chapter 6: Commotion in the Hills)

__________________________________________

[1] The pay clerk was Sergeant Peter F. Sullivan, of New York City, one time cashier of Sterling National Bank & Trust Company.

[2] Quoted from a field report.

[3] Purpose of fierce Jap resistance at San Joaquin was to prevent the 24th Division from joining contact with the XXIV Corps which had invaded Leyte Island farther to the south. At that time the 24th Division had already estab lished contact with the 1st Cavalry Division which had landed to the north, near Tacloban.

[4] Many Japanese are able to speak English but are unable to pronounce the Anglo-American “L.”