Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Historical Essays, by J. B. Lightfoot (published 1896).

(Continued from Part 2)

On the two preceding Tuesdays I discussed the relations of the early Christian to the world without, first as a member of society, and secondly as a unit in the State. In this third and concluding lecture I shall consider his relations to the Church. We have watched him hitherto in the heat of the conflict with external powers; we shall see him now arming himself for the struggle in the privacy of the Christian brotherhood. My subject this evening will be Christian life within the Christian body, and more especially Christian worship as the soul of that life.

To the careless heathen bystander this inner life of the Christian was strangely anomalous and perplexing. Such glimpses as he might accidentally obtain revealed a state of things of which he had no experience, and to which he could attach no meaning. He found nothing on which the eye or the hand could fasten. It was all so vague, so unsubstantial, so intangible and elusive. There were no external emblems and no imposing rites, without which religion seemed to him to be an impossibility.

Again and again the heathen antagonists of Christianity give expression to their surprise in the same taunting language, “You have no images, no, altars, no temples.” The principal squares and streets of Rome or Athens were lined with sanctuaries and dotted with altars; public thoroughfares and private houses were thronged with statues of gods and demigods; the language of the common people bristled with invocations of deities; the air reeked from time to time with the fat of victims or the fumes of incense. When Caligula ascended the imperial throne the festivities extended over three whole months, and 160,000 victims were sacrificed in Rome alone. When during the reign of M. Aurelius a deadly pestilence broke out, the Emperor summoned to the metropolis the priests of all religions, national and foreign, and the city was given over to lustrations, sacrifices, and rites of every kind and every country. To all this the bald simplicity of Christian worship stood in marked contrast.

Even the Jews presented a religious problem which the heathen found it difficult to solve. He was perplexed to learn that they had no external object of worship. But at all events they had a temple rich with marble and gold; they had altars smoking with sacrifices; they had priests arrayed in priestly robes. Here was something which he could understand. But in Christianity he found nothing of the kind. A silent mysterious gathering at stated times in some obscure private dwelling seemed to exhaust the religion of this anomalous sect.

His inference, though strangely at fault, was not altogether unnatural. These Christians, he supposed, were Atheists. Under cover of religion they were hatching some vile conspiracy. He had stumbled on another of those secret clubs, those illegal associations, which his jealous suspicions were ever on the watch to detect.

This strange misconception he persistently maintained. Atheism was the indictment brought against Flavius Clemens, the cousin of Domitian, when he was condemned to death for his adhesion to the new faith. “Away with the Atheists!” was the common war-cry of the persecutor. In vain the Apologists attempted to explain. “What image can I make of God,” wrote one, “when rightly considered man himself is God’s image? What temple can I build to Him, when the whole world wrought by His handiwork cannot contain Him?… The offering acceptable to Him is an honest spirit and a pure mind and a sincere conscience. These are our sacrifices; these are God’s rites. Thus with us he is the better worshipper who is the more upright man. By this we believe that God is, because we can apprehend Him, though we cannot see Him.” To all such explanations the heathen had a ready answer, “Show us your God.” This seemed to put an end to the controversy. The Christian could not satisfy the test. He had nothing to show; nothing which in the eyes of the heathen counted for religion; nothing but a firm faith and a heroic courage and clean hands and a blameless life.

From these notices it is evident that during the early centuries the ritual of the Christians was very simple. One point at least seems clear, that they were not yet in the habit of erecting buildings devoted solely to divine worship.

This, however, was not a principle of their faith, but rather a necessity of their position. As a corporation they were not recognized by the law; it was therefore impossible for them to hold corporate property. Moreover, common prudence would deter them from any display which might arouse the fury of the populace, or invite the repression of the magistrates. Hence there is not, so far as I am aware, any explicit notice of a church erected either at Rome or in the provinces before the close of the second century. Beyond the limits of the Empire the case would be different. In Syria, for instance, where the kings of Edessa early embraced Christianity, no such restraints would be imposed upon the Christians. Accordingly, as early as the year 202, when a sudden inundation swept over the city of Edessa, destroying the royal palace, the city walls, and other important buildings, the “temple of the Church of the Christians” is mentioned among the edifices thus demolished. The expression points to a building of some pretensions. How long it had been standing we do not know; but there is no reason to suppose that it was either the first or the only erection of the kind. But meanwhile, in the Metropolis and in the great cities of the Empire, the meetings for public worship would be held in a commodious room attached to the residence of some private Christian. “Where do you assemble?” asks the Roman prefect of Justin Martyr, when brought before him for trial. “Where each man will and can; thinkest thou that we all meet in the same place?” is the reply. “Tell me,” the prefect urges again, “where do you assemble; in what place dost thou gather thy disciples together?” “I have lodged,” he replies, “over the house of Martin at the Timotine bath during the whole of my present stay. This is my second visit to the city of Rome; and I know no other place of meeting besides his house.” A period of a century and a quarter has now elapsed since those first gatherings of the Apostles after the Resurrection; yet still the disciples, as of old, meet in an upper room, for fear, not now of the Jews, but of the Gentiles.

But when the first quarter of the third century had run out, their condition was much improved. The favour which Alexander Severus showed towards them could not fail to produce an immediate effect. The answer of this emperor, when a dispute arose between the Christians and the licensed victuallers about the possession of a certain piece of ground in Rome, is well known. “It is better,” he said, ” that God should be worshipped in the place in whatever manner, than that it should be given over to the victuallers.” Such a verdict from such lips would naturally give a great impulse to church-building. Yet notwithstanding, so long as they were unrecognized by the law, their tenure was altogether precarious. The disability, however, was soon removed. About the year 260 the Emperor Gallienus issued a rescript prohibiting any interference with the Christians, and expressly restoring to them their “places of worship.” By this rescript all obstacles to the multiplication of churches were at length removed.

Thus we find ourselves confronted by a broad fact, which cannot fail to suggest important reflections. During the first century and a half of its existence, Christianity in the Roman Empire had no churches, as we understand the term; while throughout the next half-century such buildings were rare and unobtrusive. Yet all this while its numbers were rapidly increasing, till it had invaded every part of the Empire, and counted its converts in every rank and department of life.

Living in an age when every church and every sect sets apart for divine worship buildings erected with some pretensions to architectural effect, when every considerable town in every Christian country bristles with the towers and spires of edifices consecrated to prayer-assembled, as we are this evening, under this glorious dome in a Cathedral which justly reckons among the masterpieces of creative genius, we cannot fail to be struck with the contrast between the present and the past. Can it be, we are led to ask, that these later forms of worship are a perversion of the simplicity of the Gospel? that we have entirely departed from the principles of primitive Christianity in the elaborate development of our architecture, our music, our ritual? A moment’s reflection will check this hasty inference which we might be tempted to draw from the contrast. I have already said that this feature in early Christianity was not a deliberate choice, but an enforced abstention. I would now urge (for this consideration is still more important) that it was also a necessary discipline, a providential design, in the early education of the Church. An example will serve to illustrate my meaning. To ourselves the stern prohibition, which some early Christian teachers placed upon the study of the ancient authors, may appear at once superfluous and illiberal. We can read our Homer or our Virgil without the slightest danger of being seduced into the worship of Zeus or Apollo; but when heathen mythology was still a living power, exercising a fatal fascination over the minds of men, the license, which we rightly claim for ourselves, might have been disastrous in the extreme. And similarly in the case before us. I pointed out in an earlier lecture how polytheism insinuated itself into every department of public duty and every corner of domestic life. But while thus ubiquitous and intrusive, it was essentially external. It made large demands on its worshippers; but these demands were confined to conformity in outward rites. It did not appeal to the heart, and it did not reform the life. The heathen did not understand religion as a moral and spiritual influence. His only conception of it was as an elaborate system of sacrifices, lustrations, auspices; a multiplication of shrines and a multiplication of deities. It was necessary, for the future of the Church, that the Christian should break once for all with the spirit of paganism. By the stern teaching of an imperious necessity, he was weaned from this false and low conception of religion. The external symbols and appliances—the buildings, the music, the paintings, and the sculptures—which may be innocent and useful to us, were denied, or almost denied, to him, that, thus thrown back upon his own spiritual resources, he might lay the foundations of a spiritual fabric. This training was to the infancy of the Church what the careful seclusion and the enforced simplicity of life is to the infancy of the individual—the necessary discipline of the child for the freedom and the development of manhood. Much that would have been injurious then, is useful—we might almost say, is indispensable—now. But ever and again in the history of the Church there have been epochs when ritual has run to excess, when the spiritual life of the Church has been threatened with suffocation from the pressure of external forms. Then a terrible reaction ensues. The iconoclast and the puritan break into the sanctuary, sweeping away in their indiscriminate zeal much that is beautiful and edifying and useful, leaving desolation in their train. Good and devout men mourn over the wholesale work of destruction; but it is God’s own chastisement, who will not allow His limits to be overstepped, and vindicates the spirituality of His Gospel at the cost of much individual pain and no little immediate loss.

Of the simple ritual which sufficed before the age of church-building began, a valuable notice is preserved in the Apologist Justin.

“On the day called Sunday,” he writes, “all those who live in the towns or in the country meet together; and the memoirs of the Apostles and the writings of the Prophets are read, as long as time allows. Then, when the reader has ended, the president addresses words of instruction and exhortation to imitate these good things. Then we all stand up together and offer prayers. And when prayer is ended, bread is brought and wine and water, and the president offers up alike prayers and thanksgivings with all his energy (or ability), and the people give their assent saying the Amen; and the distribution of the elements, over which the thanksgiving has been pronounced, is made so that each partakes; and to those who are absent they are sent by the hands of the deacons. And those who have the means and are so disposed give as much as they will, each according to his inclination; and the sum collected is placed in the hands of the president, who himself succours the orphans and widows, and those who through sickness or any other cause are in want, and the prisoners, and the foreigners who are staying in the place, and, in short, he provides for all who are in need.” Justin then goes on to explain why Sunday is selected for these assemblies, as the day at once of the Creation from chaos and of the Resurrection of Christ from the dead. And he adds in conclusion: “If these proceedings seem to you agreeable to reason and truth, pay respect to them; but if they seem to be foolishness, then treat them with contempt as foolish things, and do not condemn to death as enemies those who are guilty of no crime.”

This notice requires little or no comment. You will have observed that Justin’s description of primitive worship, written more than seventeen centuries ago, contains all those elements which to the present time are held requisite to the completeness of divine service: the reading of the Gospels and the Prophets, lessons from the Old and the New Testament; the words of exhortation, or sermon; the prayers and thanksgivings, the minister leading and the congregation responding; and lastly, as the climax to which all the previous service leads up, the Eucharistic celebration, the Holy Communion, which is the supreme act of Christian worship, at once the strongest pledge of brotherly love and the highest means of spiritual grace.

In some points we may trace divergences from the present usage of our own or other churches. Thus, for instance, the attitude of prayer is a standing position, following the common practice in ancient times. Thus, again, it is difficult to say how far the prayers and thanksgivings were written or extempore, but it seems that the latter was not altogether excluded. And again, the Eucharistic wine was diluted with water. It was commonly taken so in ancient banquets; and in the Christian festival a symbolic reference to the water and the blood would recommend the mixing for this sacred purpose. But these are minor details, not affecting the main character of the service. In all essentials we are struck with the continuity of Christian worship, when we compare its primitive form in this earliest record with its latest developments as we witness them ourselves.

But I cannot dismiss this subject without calling your attention to the practical measures which flowed immediately from these gatherings for worship. The collection of alms to be distributed to the orphan and the prisoner, to the sick and the stranger, is regarded by Justin as an inseparable part of divine service. His narrative seems to put in a working shape the Apostle’s maxim, “He that loveth not his brother whom he hath seen, how can he love God whom he hath not seen?” Without practical benevolence there can be no true worship. “He prayeth best who loveth best.”

How fully alive the early Christians were to this truth of truths, this notice at once suggests. It exemplifies that distinguishing feature of Christianity which we may call its chivalry. By chivalry I mean the temper which throws its shield over the weak, which looks upon inability as its special charge, which finds its highest satisfaction in helping those who cannot help themselves. If we cast an eye over any Christian country now, we find it dotted over with ragged schools, orphanages, reformatories, hospitals, convalescent homes, idiot asylums, charitable institutions of all kinds for the relief of misery and helplessness and want. Such appliances seem to us the indispensable accompaniments of an advanced stage of society; for without these compensations, imperfect as they are, the inequalities of social life, aggravated by a high state of civilization, would become intolerable. Yet when we look back to the great days of ancient Rome, before the example of the Christians had begun to tell upon the heathen, we can hardly see the faintest traces of any such institutions.

Their foundations were laid in those quiet little prayer meetings held every seventh day in a retired upper chamber of some humble quarter like the Trastevere, in the careless, magnificent, pleasure-seeking city.

But before the age of church-building began, Christian worship had been localized in an unexpected quarter, dictated partly by a sentiment of piety and partly by the force of circumstances. The scene now changes from the vacant room in a private dwelling to the dark passages and chambers of an underground cemetery.

While the Roman law strictly prohibited the erection of churches by the Christians, it offered no impediment to the foundation of cemeteries. The honours paid to the dead were a main element in the religion of the Roman. He scrupulously respected the rights of sepulture in the case of others, as he valued them in his own.

A Roman of the middle classes would, almost as a matter of course, belong to some burial-club or guild or confraternity, which provided for the due performance of the last offices over him on his decease. These guilds were recognized and enrolled by the government. The bond of union was various; the members would belong to the same family or the same locality or the same trade. Sometimes the link of connexion would be purely sentimental, or even altogether arbitrary. Each guild had its own burial-place, which was duly surveyed and registered by the State.

The Christians would have no more difficulty than any other body in forming such associations. The Romans, indeed, were accustomed to burn their dead at this time; while Christian sentiment dictated burial as the right mode of sepulture, reproducing, as it does, the Apostolic image of the seed sown in the ground, to spring up hereafter into a new and luxuriant life. But this fact presented no obstacle to their recognition, and indeed would hardly provoke a remark. The Jews also buried their dead, and yet they were freely recognized. Indeed, this had till very lately been the common practice with the Romans themselves. The ancient usage still lingered in some places. It was still recognized by an old law—perhaps disused, though not repealed—which directed that, when a body was burned, one limb should be cut off and buried in the earth.

Of this privilege, which the Roman law of sepulture extended to them, the Christians gladly availed themselves. If they were refused recognition collectively as Christians, they might obtain it sectionally as burial-clubs. Their religion was prohibited, but their sepulture was free. The first occasion on which a Roman bishop appears in any official relation to the government is in the earliest years of the third century, when Callistus, then Archdeacon of Rome, as president of one of these guilds, takes charge of the catacomb which still bears his name. This was not the earliest, but it is the most famous of the catacombs.

But what is a catacomb? Before answering this question, I will ask you to accompany me on visit to the great Appian Way which spans the Campagna southward from Rome. The Romans were the great road – makers of the world, and the Appian is confessedly the queen of roads. You will remember Milton’s description of the pageantry which thronged this great thoroughfare of nations—

“The conflux issuing forth, or entering in:

Prætors, proconsuls to their provinces

Hasting, or on return, in robes of state;

Lictors and rods, the ensigns of their power;

Legions and cohorts, turms of horse and wings;

Or embassies from regions far remote,

In various habits.“

Far away this road stretches in one long straight unbroken line, across the plain, up the hill slope which bars the horizon, till dipping below the summit it is lost to the eye. On either side, for a distance of ten or twelve miles at least, it is lined with splendid monuments of various designs—some so huge that they served as fortresses in the middle ages, others smaller in size, but all alike, or almost all, betokening lavish expenditure or artistic skill. I am speaking of the time with which we are immediately concerned—the second and third centuries of the Christian era; but even now, if you visit this famous Way, as I have visited it, on some fine bright winter afternoon, when the sun is low in the west, and these dismantled wrecks of the past, rising up gaunt and spectre-like, fling across the ancient pavement their long shadows jagged by the ancient kerbstones, which still fence it in—even now, in its forlorn and rueful state, faded and stripped, it impresses the imagination with a sense of past magnificence and beauty, which I dare not hope by any description of mine to reproduce. And these are the sepulchres of the mighty dead of Rome—the Scipios, the Servilii, the Metelli, men who won for themselves an undying name in the records of their country.

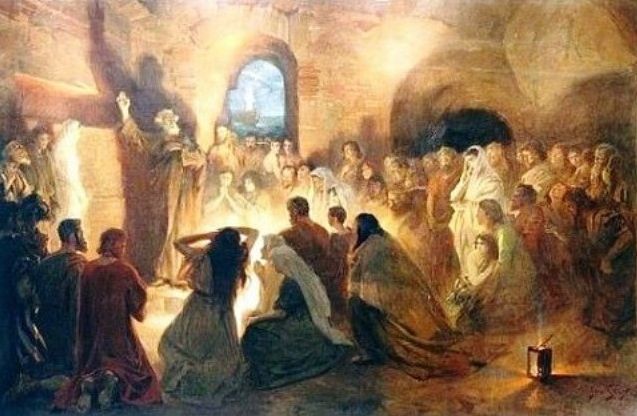

I will now ask you to visit a very different scene. You are still on this same road, and about a mile and a half from the city gate you diverge. Then, passing through a narrow doorway and down a steep flight of steps, you find yourself in a catacomb. The contrast is as great as could well be imagined. You have suddenly exchanged the light and splendour of a great Roman thoroughfare, its architectural beauty and its lavish magnificence, for an interminable warren of dark subterranean vaults and passages. This is the Christian place of sepulture, as the other was the heathen. You examine it more narrowly. You find that it is an endless labyrinth of long narrow galleries, intersecting each other nearly at right angles, and extending you know not how far. Here and there (but these are rare exceptions) they open out into small chambers. As you grope your way by the uncertain aid of a torch or a candle (for there is no light from the upper air), you see that these passages are lined on both sides from the floor to the roof with long, low, horizontal niches excavated in the native rock, rising one above another in tiers, like the shelves in a wardrobe or the berths in a ship’s cabin. There will generally be five or six of these tiers, sometimes as many as twelve. Each contains a dead body. They are hermetically sealed, and the slab which covers them is inscribed with a name. But this investigation has not exhausted the extent of the catacomb. As yet you are only traversing its first floor; there is yet another story arranged in the same way, to which you descend by another flight of steps; and again another and another. In the catacomb of St. Callistus, which apparently dives deepest into the bowels of the earth, not less than six successive floors are found. Now read the inscriptions: you will find them ill-composed, ill-written, not infrequently ill-spelt, half Latin, half Greek. Or look at the paintings (for there are paintings here and there in the chambers): they are very rude for the most part, inartistic in design and clumsy in execution, showing neither a cultivated imagination nor a practised hand.

I have introduced you to one catacomb, which will serve as a type of all. If you extend your search you will find that these subterranean cemeteries encircle Rome with a vast girdle, which, roughly speaking, passes between the second and third milestone from the gates, intersecting the great roads which radiate from the city like spokes of a wheel, and from which access is gained to these several lodging-houses of the dead. In this zone the ground is honeycombed with their labyrinthine corridors and chambers, hollowed out in the soft tufa stone, the deposit of extinct volcanoes in prehistoric ages. Wherever this tufa is neither too hard to be easily and inexpensively worked, nor too soft to sustain when excavated the superincumbent weight, a catacomb is almost sure to be found. It has been estimated that the united length of all these galleries would amount to three hundred and fifty, to six hundred, even to eight hundred or nine hundred miles. All such estimates must be regarded only as very rough conjectures, as their wide difference shows; but they will enable us in some degree to realize the enormous number of bodies which are congregated in this vast city of the dead.

We have visited in succession the necropolis of the heathen and the cemetery of the Christian, the Appian Way above ground, and the Appian Way beneath the soil; and we have marked the startling contrast. This contrast, one might say, is in all respects unfavourable to the Christians. On the one hand you have the free air, the bright sunshine, the blue sky, the lavish expenditure of wealth, the display of constructive and decorative skill—in short, all the advantages of nature and all the appliances of art combined. All here is intelligence and beauty and brightness and magnificence. Can we add, all is cheerfulness? On the other hand, when you dive into the Christian cemetery, you have none of these things; all the accompaniments of the place are utterly depressing, you would say: illiterate inscriptions, rude paintings, a damp close atmosphere, an impenetrable prison-like gloom. All is monotony, confinement, darkness—and you might be tempted to add, all is despair. But your curiosity is aroused, and you study and compare the sepulchral inscriptions of these two cities of the dead. The epitaphs of a people or an age are no treacherous indications of its mind. And here a study of these voices from the past entirely reverses your first crude impression. With all its light and splendour, the utterance of the above-ground necropolis is one long wail of despair: there are touching expressions of natural affection, beautiful in themselves, but not one ray of glory pierces the dark cold shadow of death. Hopelessness, utter hopelessness, is traced in every line. The external magnificence is like the jewels and the finery which render more ghastly by contrast the bloodless features of the corpse which they bedeck. Turn to the Christian inscriptions, and all is changed. Neither bad grammar nor defective orthography, nor rude art nor cramped space, nor damp nor darkness can dim or distort the light with which the consciousness of an immortality floods and glorifies these subterranean vaults. All here is joy and brightness and hope. The often-repeated inscription “In peace” tells its own tale. The paintings are all conceived in the same spirit. Now it is the dove or the palm branch, emblems of love, of innocence, and of victory. Now it is the Good Shepherd, tenderly bearing on his shoulders the feeble or the maimed one of the flock. And now again it is a heathen subject adopted and transfigured by a Christian baptism. Orpheus, thrilling, entrancing, dissolving the souls of men with the ecstasies of his unearthly music—not failing now to “quite set free His half-regained” spouse, but presenting her, ransomed and sanctified without spot or wrinkle before the Eternal throne, triumphing over death on His cross and in His grave, and thus in a new and a higher sense

“Making Hell grant what Love did seek.”

And even when subjects of a more painful interest are chosen, and the Christian is reminded of the persecutions which he may be called at any moment to endure, they are still treated in a manner which suggests the anticipation of victory. The favourite themes are Daniel praying fearlessly among the hungry lions, and the Three Children singing the song of praise in the flames of the heated furnace. The catacombs signally vindicate the Apostolic law of “strength made perfect in weakness.”

It has often been assumed that these underground cemeteries were the common places of assembly for the Christians. This seems to be a mistake. The space is too confined and the arrangement too inconvenient for any large gathering of people. Nor indeed was it necessary in ordinary times to resort to such obscure hiding-places. If he were only careful not to provoke interference, the Christian might generally hold his meetings unmolested in the upper air. But in seasons of trouble and danger the catacomb was at once the asylum of the fugitive and the church of the worshipper. A Roman’s respect for the dead would generally secure these cemeteries from molestation. But when the fury of the populace was aroused, even these sanctuaries were invaded. It was a new aggravation of wrong when, in the Valerian persecution, these cemeteries were invaded by authority, and the Christians hunted down in their hiding places. But cruelties which the government was slow to adopt were often anticipated by the violence of the people. An inscription from a catacomb, purporting to belong to the reign of Antoninus, gives a lively picture of these moments of terror. “Alexander,” so it runs, “is not dead, but lives beyond the stars, though his body rests in this tomb. Bending his knees to offer sacrifice to the true God, he is led away to execution. O unhappy times, when amidst worship and prayer we cannot be safe even in caves. What is more wretched than life; yet what is more wretched in death than to be denied burial by friends and parents?” At such times the fugitives would secure their hiding-places by walling off corridors and blocking up entrances, while they provided an egress by piercing some new passage into the upper air.

But the Christian was drawn to the catacombs not less by the sentiment of piety than by the instinct of self-preservation. For here were the graves of the martyrs. It is painful to think how very soon the reverence for the heroism and saintliness of those who had suffered for the faith degenerated into a mere worship of relics. But I speak now of a time when a healthier tone prevailed. The memory of their sufferings was yet too fresh, and the sympathy of the living with the dead too real, for any very gross corruption of a sentiment so pure and noble. As the survivors met in some underground chamber over the grave of a martyred friend, and consecrated the eucharistic elements on the very slab which covered his remains, carrying their own lives in their hands, and eating their Christian passover, as of old, in haste and trembling, their loins girt and their feet shod, expecting at any moment the alarm which should summon them forth on their last long journey, they could not but feel themselves one with those who had gone before, one in their sympathies, one in their struggles, one in their hopes. The barrier between death and life dissolves before a great crisis which reveals the Eternal Presence. At such moments the continuity of existence is felt. The Christian realizes his communion with the past and the future; and feeling that he is no more an isolated unit floating in a boundless void, he nerves himself with that strength of purpose and that assurance of hope which the sense of association alone can give.

With this thought, which though old is ever new, I will conclude. If I have succeeded in exciting in any one member of this congregation a desire for a more familiar acquaintance with the records of his spiritual ancestry in primitive times; if I have struck out in one intelligent heart a fresh spark of sympathy with the grand historic past; if only a single hearer has carried away from these lectures, into the fretting cares and distractions and trials of daily life, one cheering memory or one heroic resolve or one ennobling thought, then the task which I set to myself has been more than accomplished. I could have desired nothing more.