Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Brave Men and Women: Their Struggles, Failures, and Triumphs, by O. E. Fuller (published 1884).

At the present writing (Summer of 1884), General Gordon, who has won the heart of the world by his brave deeds, is exciting a great deal of interest on account of his perilous position in Khartoum. A sketch of his career will be acceptable to not a few readers.

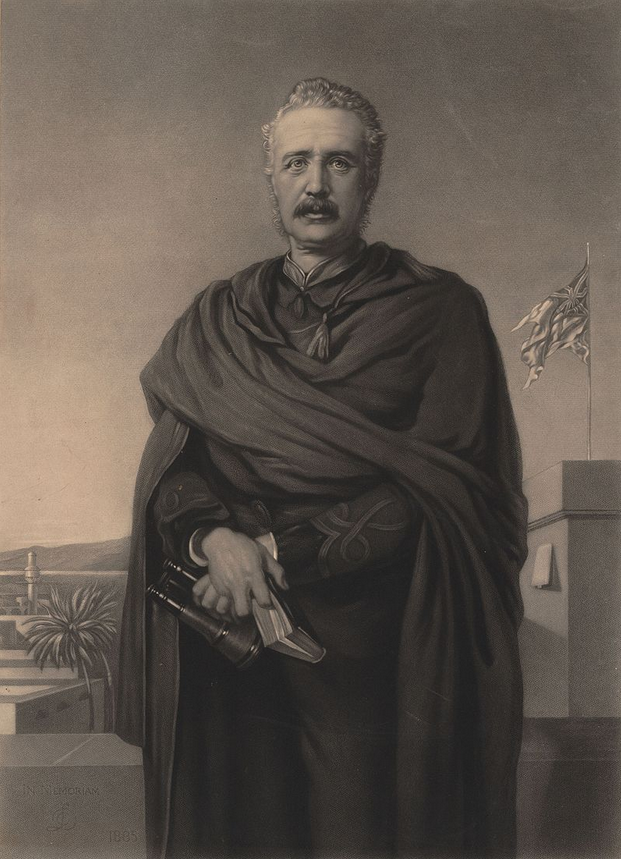

The likeness which accompanies this chapter is from a photograph taken not long ago at Southampton, England; but no portrait gives the expression of the man. His smile and his light-blue eyes can not be painted by the sun. The rather small physique, and mild and gentle look, would not lead the ordinary observer to recognize in General Gordon a ruler and leader of men; but a slight acquaintance shows him to be a man of unusual power and great force of character.

His religious fervor and boundless faith are proverbial–so much so that some men call him a fatalist; whilst others say, like Festus, “Thou art beside thyself.” Neither of these judgments is true, though it is certainly true that, from a desire to oblige others, Gordon has sometimes made errors in judgment that have led him into sad dilemmas. To say nothing of his second visit to the Soudan, to oblige Ismail Pasha, and his rash and most dangerous embassy to King John of Abyssinia, to oblige Tewfik Pasha, we need but allude to his unwise acceptance of the post of private secretary to Lord Ripon in India. He was overpersuaded, and to please others he sacrificed himself. To those who knew him, it was not surprising that almost the first thing he did on landing at Bombay was to throw up his appointment and rush off to China, where he was instrumental in preventing war between that country and Russia.

The active life of General Gordon, who is about fifty years old, may be divided into the following sections: the Crimea and Bessarabia; China (the suppression of the Taiping rebellion); Gravesend (the making of the defenses at Tilbury); and the Soudan. A later and shorter episode occurs in his visit to Mauritius and the Cape, the latter colony being the only place in which his great capabilities and high character were unappreciated.

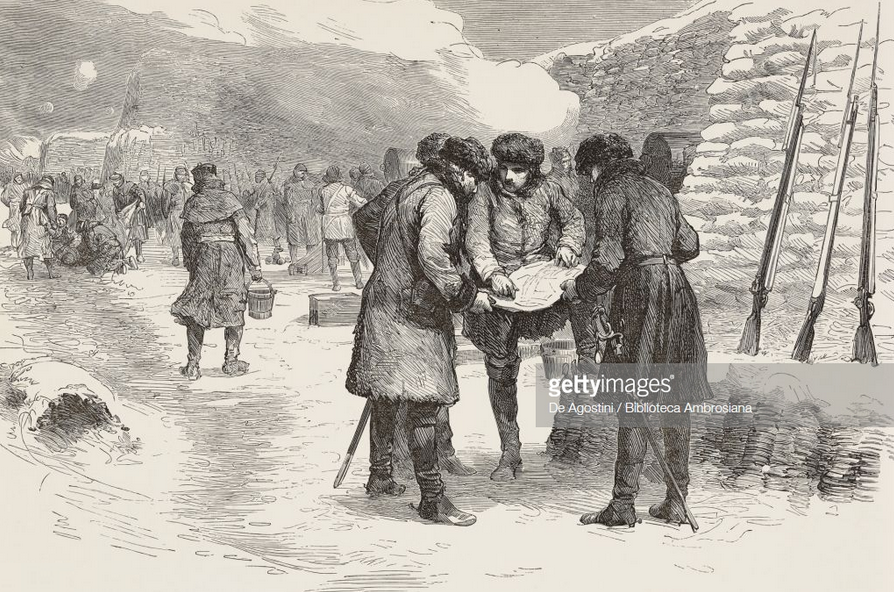

In the Crimea General Gordon worked steadily in the trenches, and won the praise of his superior officers for his skill in detecting the movements of the Russians. Indeed, he was specially told off for this dangerous duty. Lord Wolseley, then a captain, was a fellow-worker with Gordon before Sebastopol.

In 1856 Gordon was occupied in laying down the boundaries of Russia, in Turkey and Roumania, for which work he was in a peculiar manner well fitted, and he resided in the East, principally in Armenia, until the end of 1858. During this time he ascended both Little and Great Ararat.

In 1860 he was ordered to China, and assisted at the taking of Pekin and the sacking and burning of the Summer Palace. This work did not seem to be much to his taste.

China was the country destined to give to the young engineer the sobriquet by which he is now best known – “Chinese” Gordon. Here he first developed that marvelous power, which he still holds above all other men, of engaging the confidence, respect, and love of wild and irregular soldiery.

The great Taiping rebellion, which was commenced soon after 1842 by a sort of Chinese Mahdi – a fanatical village schoolmaster – had attained such dimensions that it had overrun and desolated a great portion of Southern China, and threatened to drive the foreigners into the sea. Nanking, with its porcelain tower, had been taken, and was made the capital of the Heavenly King, as the rebel chieftain, Hung, now called himself. His army numbered some hundreds of thousands, divided under five Wangs, or kings, and the Imperialists were driven closer and closer to the cities of the seacoast.

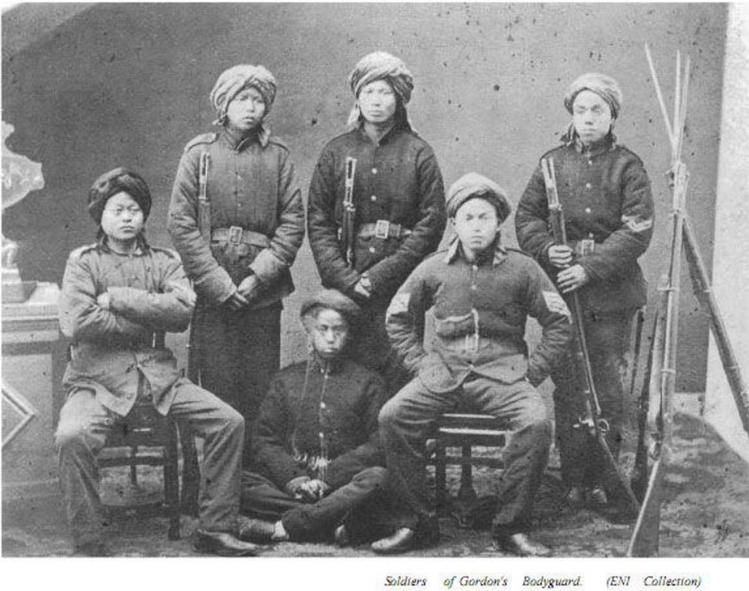

In 1863 the British Government was applied to for assistance, and Captain Gordon was selected to take command of the Imperial forces in the place of an American adventurer named Burgevine, who had been cashiered for corrupt practices. The Ever-victorious Army, as it was called, numbered 4,000 men, when the young engineer took the command. Carefully and gradually he organized and increased it, and as he always led his men himself, and ever sought the post of danger, he soon obtained their fullest confidence, and never failed to rally them to his support.

He wore no arms, but always carried a small cane, with which he waved on his men, and as stockade after stockade fell before him, and city after city was taken, that little cane was looked upon as Gordon’s magic wand of victory. He seemed to have a charmed life, and was never disconcerted by a hailstorm of bullets. Occasionally, when the Chinese officers flinched and fell back before the terrible fusillade, he would quietly take one by the arm and lead him into the thickest of the enemy’s fire, as calmly as though he were taking him in to dinner. Once, when his men wavered under a hail of bullets, Gordon coolly lighted his cigar, and waved his magic wand; his soldiers accepted the omen, came on with a rush, and stormed the defense. He was wounded once only, by a shot in the leg, but even then he stood giving his orders till he nearly fainted, and had to be carried away.

Out of 100 officers he lost almost one-half in his terrible campaign, besides nearly one-third of his men. But he crushed the rebellion, and rescued China from the grasp of the most cruel and ruthless of spoilers. His own estimate was that his victories had saved the lives of 100,000 human beings.

Then he left China without taking one penny of reward. Honors and wealth were poured at his feet, but he accepted only such as were merely honorary. He was made a Ti-Tu–the highest title to which a subject can attain–and he received the Orders of the Star, the Yellow Jacket, and the Peacock’s Feather. When, however, the Imperial messengers brought into his room great boxes containing £10,000 in coin, he drove them out in anger. The money he divided amongst his troops. And yet he might well have taken even a larger sum. One who knew how deeply the empire was indebted to him, wrote, “Can China tell how much she is indebted to Colonel Gordon? Would 20,000,000 taels repay the actual service he has rendered to the empire?”

Gordon returned home to England, and, avoiding all the flattering notice that was continually thrust upon him, he retired to his work at Gravesend, where, from 1865 to 1871, he labored at the construction of the Thames Defenses.

Here he passed six of the happiest years of his life–in active work, in deep seclusion from the world of wealth and fashion, but in a state of happiness and peace. His house was school, hospital, and almshouse, and he lived entirely for others. “The poor, the sick, the unfortunate were welcome, and never did supplicant knock vainly at his door.”

Gutter children were his especial care. These he cleansed and clothed, and the boys he trained for a life at sea. His evening classes were his delight, and he read and taught his children with the same ardor with which he had led the Chinese troops into battle. For the boys he found suitable places on board vessels respectably owned, and he never lost sight of his proteges. A large map of the world, stuck over with pins, showed him at a glance where he had last heard from one of these rescued waifs. “God bless the Kernel,” was chalked upon many a wall in Gravesend; and well might the poor bless the man who personified to them the life and daily walk of one who “had been with Jesus.” To them he was the “Good Samaritan,” pouring in oil and wine; and they blessed and reverenced him, and gave him a love which he valued more than royal gifts.

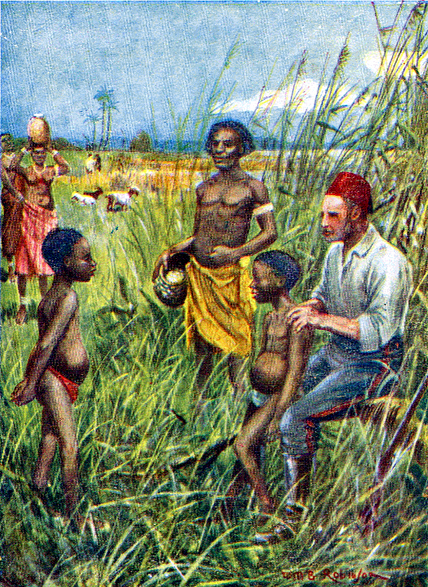

We must, however, hasten on, and see him transferred from Gravesend to the Danube, and thence to the Soudan. He succeeded Sir Samuel Baker in the government of these distant territories in Egypt in 1873. The Khedive Ismail offered him £10,000 a year, but he would only accept £2,000, as he knew the money would have to be extorted from the wretched fellaheen. His principal work was to conquer the insurgent slave-dealers who had taken possession of the country and enslaved the inhabitants. The lands south of Khartoum had long been occupied by European traders, who dealt in ivory, and had thus “opened up the country.” This opening up was a terrible scourge to the natives, because these European traffickers soon began to find out that “black ivory” was more valuable than white. So they formed fortified posts, called sceribas, and garrisoned them with Arab ruffians, who harried the country and organized manhunts on a gigantic scale. The profits were enormous, but the “bitter cry” of Africa began to make itself heard in distant Europe, and the so-called Christian slave-dealers found it more prudent to withdraw. This they did without loss, for they sold their stations to Arabs, and the trade in human beings went on as merrily as ever. Dr. Schweinfurth, the African explorer and botanist, visited one of these slave-dealing princes in 1871, and found him surrounded by an almost regal court, and possessed of more than vice-regal power. He was lord of thirty stations, all strongly fortified, and stretching like a chain into the very heart of Africa. Thus his armies of fierce soldiery, Arab and black, were able to make raids over whole provinces, and gather in the great human harvest to supply the demands of Egypt, Turkey, and Arabia. This famous man was named Sebehr Rahma; and although he was defeated by Colonel Gordon and sent down to Cairo, he never quite lost favor at the Egyptian Court, and was not long since appointed commander in chief of the Soudan, to uphold the power of Egypt against the Mahdi! The scandals of the slave-trade, combined with the lust of conquest, were the causes out of which grew the famous expedition of Sir Samuel Baker to the Soudan. The love of conquest made it pleasing in the eyes of the Khedive Ismail, and the desire to uproot the infamous slave-trade obtained for the enterprise the warm approval of the Prince of Wales, and the hearty co-operation of Sir Samuel Baker, who displayed the greatest courage and energy in the conduct of the enterprise.

From this first expedition the two succeeding ones of Colonel Gordon may be said to have arisen. The struggle against the slave-hunters had developed into a war, and the Khedive began to fear that their power would grow until his own position at Cairo might become endangered. The slave-king Sebehr must be destroyed, together with his numerous followers and satellites.

Gordon was not long in perceiving why he was selected for the office of governor; for we find him writing home, “I think I can see the true motive of the expedition, and believe it to be a sham to catch the attention of the English people.” With him, however, it was no sham. He was determined to do what he was professedly sent to do, viz.: put down the slave-trade. “I will do it,” he said, “for I value my life as naught, and should only leave much weariness for perfect peace.”

How hard he found his task to ameliorate the condition of the wretched inhabitants, we perceive from such an outburst as this, amongst many similar: “What a mystery, is it not? Why are they created? A life of fear and misery, night and day! One does not wonder at their not fearing death. No one can conceive the utter misery of these lands–heat and mosquitoes day and night all the year round. But I like the work, for I believe I can do a great deal to ameliorate the lot of the people.”

This spirit of unselfishness and of a sublime charity runs through all his work. Every man, black or white, was “neighbor” to him, and he ever fulfilled the command of his Lord, to “love his neighbor as himself.” Against oppression he could, however, be stern and severe. Not a few ruffians whom he caught red-handed in flagrant acts of cruelty were executed without mercy. So that the same man who, by the down-trodden people, was called the “Good Pasha,” was to the robber and murderer a terror and avenger.

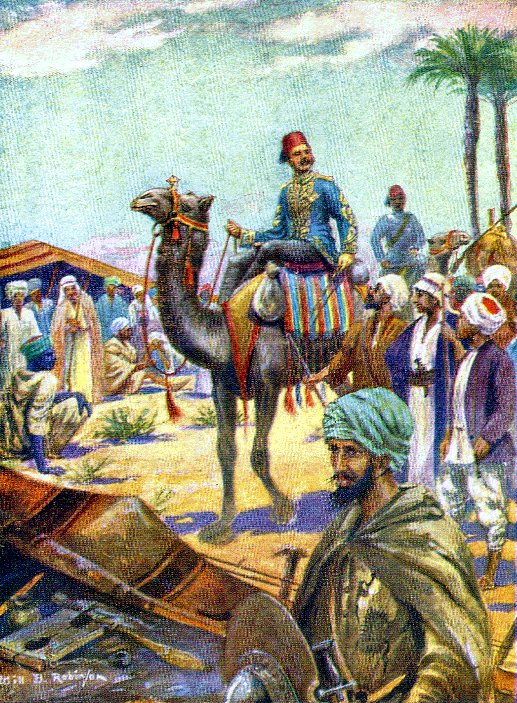

When at Khartoum he was on one occasion installed with a royal salute, and an address was presented, and in return he was expected to make a speech. His speech was as follows: “With the help of God, I will hold the balance level.” The people were delighted, for a level balance was to them an unknown boon. And he held it level all through his long and glorious reign, which lasted, with small break, from February, 1874, until August, 1879.

During those five years and a half he had traveled over every portion of the huge territory which was placed under him–provinces extending all the way to the Equatorial Lakes. Besides riding through the deserts on camels and mules 8,490 miles in three years, he made long journeys by river. He conveyed a large steamer up the Nile as far as Lake Albert Nyanza, and succeeded in floating her safely on the waters of that inland sea. He had established posts all the way from Khartoum to Gondokora, and reduced that enormous journey from fifteen months to only a few weeks. He writes respecting these posts in January, 1879: “I am putting in all the frontier posts European Vakeels, to see that no slave caravans come through the frontier. I do not think that any now try to pass; but the least neglect of vigilance would bring it on again in no time.”

This is only one out of hundreds of instances of the hawk-eyed vigilance of the governor-general. The vast provinces under his sway had never been ruled in this fashion before.

One strain runs through all his numerous letters written during the five years he remained in the Soudan, and that is the heart-rending condition of the thousands of slaves who were driven through the country, and the cruelty of the slave-hunters. Were we to begin quoting from those letters, we should outrun the limits of this sketch. He had broken the neck of the piratical army of man-stealers, and their forces were scattered and comparatively powerless. So many slaves were set free that they became a serious inconvenience, as they had to be fed and provided for.

And yet there was no shout of joy at the capital, whence he had set out years before, armed with the firman of the khedive to put an end to the slave trade. On the contrary, We find him saying: “What I complain of in Cairo is the complete callousness with which they treat all these questions, while they worry me for money, knowing by my budgets that I can not make my revenue meet my expenses by £90,000 a year. The destruction of Sebehr’s gang is the turning-point of the slave-trade question, and yet, never do I get one word from Cairo to support me.”

One more extract:

“Why should I, at every mile, be stared at by the grinning skulls of those who are at rest?

“I said to Yussef Bey, who is a noted slave-dealer, ‘The inmate of that ball has told Allah what you and your people have done to him and his.’

“Yussef Bey says, ‘I did not do it!’ and I say, ‘Your nation did, and the curse of God will be on your land till this traffic ceases.'”

This man, Yussef Bey, was one of the most cruel of the slave-hunters, and renowned for the manner in which he tortured his victims, more especially the young boys. He also cruelly murdered the interesting and peaceful king of the Monbuttos, so graphically described in Schweinfurth’s “Heart of Africa.”

In June, 1882, Yussef Bey met his deserts, for going out with an army of Egyptian troops to meet the Mahdi, he and all his men were cut to pieces, scarcely one surviving.

Much of Gordon’s time, during his first expedition, had been occupied in strengthening the Egyptian posts south of Gondokoro, stretching away toward the country of King M’tesa. So badly were they organized that it took him twenty-one months to travel from Gondokoro to Foweira and Mrooli, his southernmost points. There he found that it would be impossible to interfere with the rival kings of that region without becoming involved in a war, and he returned from the lake districts “with the sad conviction that no good could be done in those parts, and that it would have been better had no expedition ever been sent.”

We conclude our imperfect sketch with the following quotation, describing General Gordon’s resignation:

“I am neither a Napoleon nor a Colbert,” was his reply to some one who spoke to him in praise of his beneficent rule in the Soudan; “I do not profess either to have been a great ruler or a great financier; but I can say this: I have bearded the slave-dealers in their strongholds, and I made the people love me.”

What Gordon had done was to justify Ismail’s description of him eight months before. “They say I do not trust Englishmen; do I mistrust Gordon Pasha? That is an honest man; an administrator, not a diplomatist!”

Apart from the difficulties of serving the new khedive, Gordon longed for rest. The first year of his rule, during which he had done his own and other men’s work, the long marches, the terrible climate, the perpetual anxieties, had all told upon him. Since then he had had three years of desperate labor, and had ridden some 8,500 miles. Who can wonder that he resented the impertinences of the pashas, whose interference was not for the good of his government or of his people, but solely for their own?

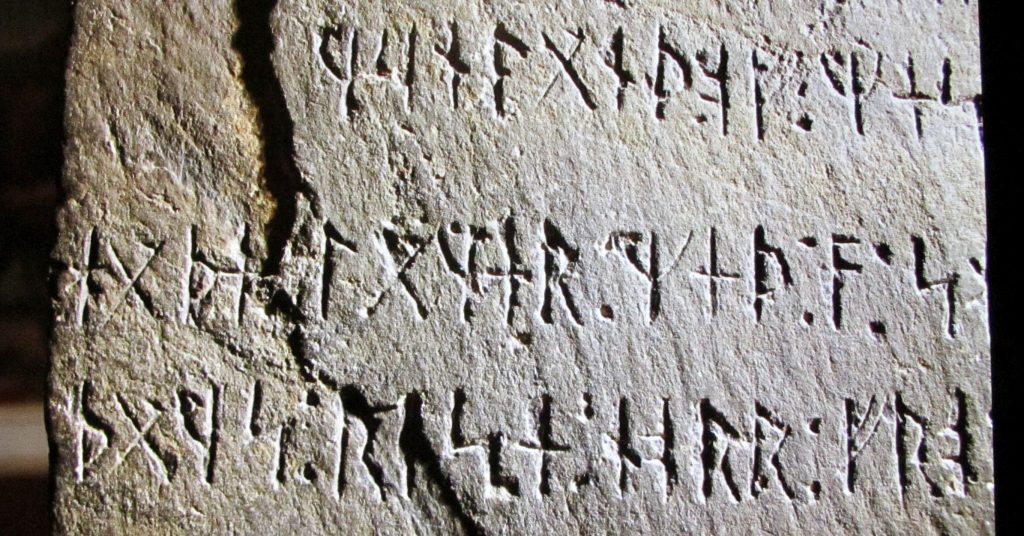

But it was not for him to stay on and complain. To one of the worst of these pashas he sent a telegram which ran, “Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin.” Then he sailed for England, bearing with him the memory of the enthusiastic crowd of friends who bade him farewell at Cairo. It is said that his name sends a thrill of love and admiration through the Soudan even yet. A hand so strong and so beneficent had never before been laid on the people of that unhappy land.

5

This is how it’s done.

A nation is its people. Men like Gordon are the true glory of a nation. The nation’s glory is determined by whether and how it uses people like this well.