Editor’s note: The following comprises Chapter 12 of Children of Yesterday, by Jan Valtin (published 1946).

(Continued from Chapter 11: Ghosts of Guadalcanal)

________________________________________________________________________

“I have been driven many times to my knees by the overwhelming conviction that I had nowhere else to go. My own wisdom, and that of all about me, seemed insufficient for that day.”

Abraham Lincoln

________________________________________________________________________

In Tunga native children cut little stops of wood with which to plug the bullet holes in the village school. The war, for them, had passed.

In Palo grown-ups and children had a liberation fiesta. On the town square the children staged a pantomime: an unwashed urchin wearing a tophat paraded on the stage; around his neck hung a sign, “President of the Philippines.” A second urchin jumped to the stage. He was disguised as a Japanese and he proceeded diligently to rifle the “President’s” pockets. Then a third little boy, garbed as “Uncle Sam,” stormed upon the stage. His bare brown foot lashed to the seat of “Nippon’s” pants; “Nippon” fled. Whereupon the “President” shook “Uncle Sam’s” hand. In Palo, too, the war had passed.

In the town of Jaro the Division Quartermaster established a supply dump. Among his supplies there was a ton of mimeograph paper which had been damaged in a rain storm. Nevertheless, the quartermasters had carried this ton of useless paper with them from dump to dump. A little girl in Jaro saw the mass of paper. “May I have a few sheets?” asked she. They were given to her. And soon other children came and asked for paper. The children told their teachers and the teachers told the principal of their school, “There is paper free for the asking at the Army Dump.” For years the school had done without paper. Next morning three hundred children filed past the dump in silent formation. Away with them they carried a ton of paper. In Jaro the war had also become a thing of the past.

Twelve miles from Jaro General Frederick A. Irving, the Division’s commander, warned higher headquarters that the road from Carigara to Pinamopoan would not support a major offensive. Higher headquarters ordered that the offensive should proceed. The road dissolved and General Irving was relieved of his command.

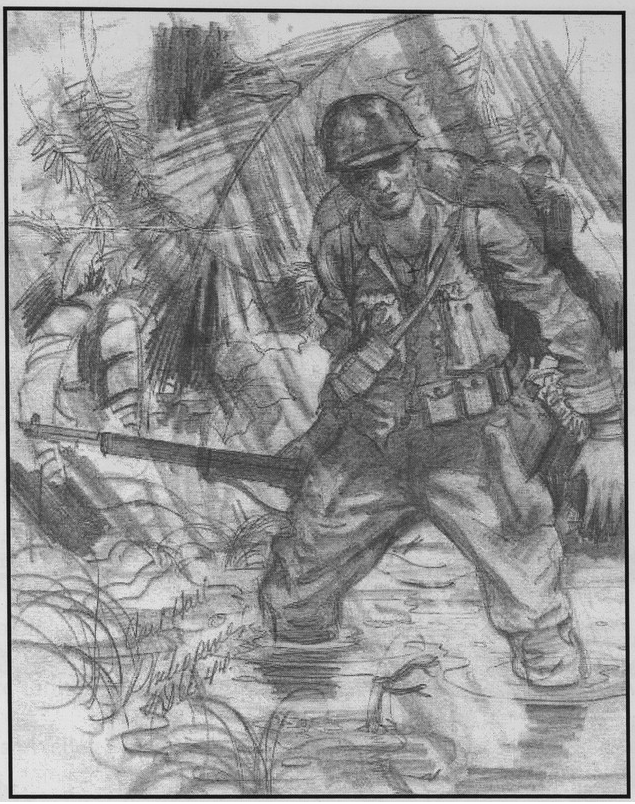

The offensive proceeded. Mud became as vicious a foe as the Japanese. Men huddled under ponchos wrote letters home; they wrote on the backs of ration boxes and of Japanese leaflets. Rain turned their letters into pulp before they could be censored. In the offensive men plunged ahead from clump to clump of swampy grass only to sink in morass up to their armpits; they were pulled out by ropes in the hands of their comrades. Each evening each man dug a hole in which to spend another miserable night. By midnight the holes had filled with water. There was lack of food, lack of dry clothing, and at times a shortage of ammunition. Supplies for the men on Breakneck Ridge bogged down in mud.

(Carl Hall Collection / Veterans History Project)

The road from Carigara to Pinamopoan, over which all supplies to the front must pass, was a blasted, mucky track. Five bridges along the road had been wrecked. The long bridge across the Carigara River had been set afire by saboteurs. Engineers bridged three streams with new wooden bridges. They bridged the Carigara River with pontoons. They also bridged the unruly Nauguisan River with pontoons. Bulldozers carved out by-passes for vehicles too heavy to negotiate the bridges. Bulldozers, too, filled craters caused by mines, and by enemy artillery firing from Breakneck Ridge. “All of this work,” explains the Division Record, “was complicated by rains which made the entire island a sea of mud.”

The Carigara-Pinamopoan road had been laid on swamp. It was no more than a rock fill which disintegrated under the pounding of heavy trucks, tanks, tractors and artillery columns. The weight of the vehicles cracked the crust of the road. Water seeped through the cracks from the swamp below. The following trucks and cannon then pressed whole patches of rock fill down into the swamp. Large holes in the road were the result. As succeeding vehicles crossed these holes, edges crumbled, and long stretches of road vanished in the swamp. Soon it became impassable even to tanks.

The Division’s engineers worked twenty-four hour shifts in a stubborn bid to keep the highway open. Long stretches of corduroy were laid. Masses of native laborers were put to work with shovels. Trucks hauled rocks from distant quarries to patch the road — instead of hauling supplies. But nothing could make the road hold up. Traffic became dependent on amphibious machines which could take to the water and skirt the beach.

But the offensive proceeded.[1]

Americans died under bullets from American machine guns which the Japanese had captured. As “Able” Company pushed up the Ormoc Trail its scouts discovered a group of wrecked American trucks whose drivers lay killed by the roadside. They thought it the work of snipers. But as they approached they saw empty ration tins littering the road for a hundred yards. The Japs had been eating American rations taken from the ambushed trucks. The scouts turned and flashed a warning. It was too late.

It was a perfect spot for a roadblock. There was an abyss on one side, a steep kunai-matted slope on the other. Out of the kunai fired American machine guns manned by Japanese. The nearest Americans were only fifteen feet away. First man to fall was the company commander; he died in the first minute of his first day in battle. Lieutenant Peter Babich of Morgantown, West Virginia, a platoon leader in the rear of the column, heard the shooting. He went forward to find out why the leading elements were falling back. He found machine gun fire coming from the front and the flank and he found many dead and others dying. The company withdrew. In the withdrawal Babich carried with him a wounded man, and then he retrieved his commanding officer’s body. Disengaged, he ordered mortar fire to reduce the roadblock.

“Able” Company battled on Breakneck Ridge through eleven consecutive days. On one day its mortar sections threw fourteen tons of shells on a single Japanese position. The pillbox, after it was stormed, was found large enough to hold seventy-five defenders. “Bloody Knob,” they called it.

A group sent out to reinforce a company which had been cut off on the slope of Suicide Hill crossed a bridge well behind the front and suddenly found itself attacked from the rear. There were Japs running and firing light machine guns as they ran. Out numbered, surrounded, the Americans dodged under the bridge. The Japanese hacked holes into the bridge and threw grenades through the openings. The men under the bridge replied by riddling the overhead planking with bullets. The weird encounter lasted three hours before the Japs gave up. They set the bridge afire before they disappeared into the flanking kunai.

“Baker” Company lost two-thirds of its effectives in fourteen days of fighting and steady rain. Its rations were hand-carried across two miles of sniper-infested terrain. “Dead Man’s Curve” the survivors renamed their sector of the Ormoc Trail.

“Charlie,” “Dog,” “Easy,” “Fox,” “George”— every company in the Twenty-First paid its blood price for the sodden wilderness of Breakneck Ridge….

November 7.

On the perimeters dug-in infantry repulsed two Banzai assaults before dawn. In the gray morning the Twenty-First Regiment attacked in a column of battalions. Its objective was a ridge four hundred yards to its front. “Easy” Company seized one section of the ridge at noon. “George” Company struck a force of Japanese while crossing a ravine. Tank destroyers were hauled forward through the mud. They pounded the ravine, without success. Then tanks joined the fight.

Around the tanks the enemy swarmed in yelling packs. A tank commander was tossing grenades out of the turret. As he was about to throw a grenade, a bullet pierced his hand. The grenade fell into the tank on top of a hundred rounds of 75 milli meter ammunition. The grenade was a dud. But a Jap jumped forward with a satchel full of dynamite and threw it against the rear of the turret. The tank was disabled.

Cooks and messengers, company clerks and musicians carried wounded men and fought in the front lines. A mess sergeant named James Nesbitt of Princeton, Arkansas, led a patrol which became scattered in an expanse of seven-foot-high grass. Nesbitt prowled in circles in an endeavor to gather the men of his group. He came face to face with an enemy sniper instead. The Arkansan fired first. At the same moment another sniper in the kunai fired at Nesbitt. The cook left the hit Jap squirming in the grass and went hunting for the second sniper. He rolled through the grass to get out of the sniper’s sights. A mortar shell exploded on the spot Nesbitt had just left. He lay still and rested a minute to shake off the effect of the concussion. Then he continued his hunt. He came upon the second sniper from the rear and shot him through the head.

When “Easy” Company was counter-attacked from the summit of the ridge, all members of an anti-tank gun crew were hit. There was now a breach in the company’s line. Private Francis Anderson of Drake, North Dakota, crawled into the gap and de fended it with nothing but his rifle. Anderson’s job was that of a messenger.

The leader of a hard-pressed platoon of riflemen was killed. The platoon had become disorganized in the melee and was in danger of annihilation. The second in command, Sergeant Schomaker of Ford, Kansas, was seriously wounded. Nevertheless, Schomaker overcame his pain and led the platoon into an organized retreat.

A Japanese raiding party charged a battalion command post. Woodrow W. Haskett, of Natrona, Wyoming, a cook, was first to spot the raiders. He rushed to a light machine gun and sprayed the oncoming Japs. Haskett continued to fire until the Japanese were less than twenty feet away. They fired, emitted wild screeches, hurled grenades. Haskett’s stand broke up the raid. But the soldier-cook from Wyoming lay dead at the side of his gun.

Meanwhile, “Love” Company carried out a wide flanking movement to the left. Its mission was to strike from the flank the ridge which “Easy” Company had been denied from the front. The maneuver failed. “Love” Company was thrown back by a vicious combination of mud, torrential rain, and a cliff-like mountainside manned by Japs. Night was near and the assault battalion was split in three ways: “Fox” Company grimly held on to the captured section of the ridge; “Easy” Company was embroiled at the rim of a canyon on the forward slope; “Love” Company dug its night defenses in the rear of the contested height. Masses of Japs held the intervening terrain.

Elsewhere on Breakneck Ridge things were not much better. Artillery fought thunderous duels. A group of artillery observers climbed 800-foot high Observation Hill. They found the Japanese fortifications empty. Happily they rigged up their radio and began to look for targets. Major Lemuel Blacker of Corvallis, Oregon, tested the radio.

“This is a wonderful spot,” he told the regimental commander. “The Japs seem to have pulled out. We’ll…”

There was a cry: “Look out!” Then there was a volley of firing and the radio went dead. Through kunai grass Japs were crawling to the edge of the trench system. An officer waving a sword leaped out of the grass, seven Japs at his heels. Submachine guns and carbines cut them down. Minutes later eight other Japs attempted to rush the trenches. All eight died. The radio came back to life. “Throw some stuff around this hill,” Major Blacker told his artillery. “In a hurry… Roger… out.”

At this time, too, the Nineteenth Infantry Regiment dispatched a company to find and seize a dominating height known as Hill 1525. A force had been sent there the previous day, but it had lost its way. Possession of Hill 1525 was vital because it could serve as a base from which artillery observers might direct fire on distant reaches of the Ormoc Trail. The task force, with native guides, struck out on a carefully plotted compass azimuth. But strong Japanese forces descending from an intermediate ridge pushed it out of its course. Again the Filipino guides lost their way in the labyrinth of ridges and ravines. Beleaguered by Japanese, the infantrymen dug their foxholes in a hillside which they thought to be in the vicinity of Hill 1525. Actually they were far to the east of their objective. In night and rain the enemy attacked.

On one company perimeter the Japanese killed a machine gun crew and seized the weapon. The company commander, Captain Robert Kilgo, was taken aback when he heard one of his own machine guns pour fire in a “wrong” direction. Though the night was irate with the whirr of bullets, Kilgo left his command post in the center of the perimeter to investigate. He found the danger spot in the flickering light of a pile of burning equipment.

Kilgo crouched low and ran back against a stream of bullets whipping from the Garands of his own riflemen. He went to a sector of the perimeter which was not under attack. There he grabbed a heavy machine gun, and with it he raced to the gap in his company’s defenses. The machine gun’s crew followed hard on their captain’s heels. Kilgo installed gun and crew in a matter of seconds. It saved the company from being cut to pieces in the dark.

In a simultaneous attack near the beach at Pinamopoan the Japs came silently, with machine guns, mortars, and bayonets fixed. Not far from the outposts they stood up and approached at a walk, chatting in English as they came. But following the rule that only the enemy moves in a tropical night, the outposts fired. Close combat followed. To create confusion, the Japs shouted in English. They shouted for aid men. They shouted names, “Charlie, come here quick, I’m in trouble.” And they shouted false fire directions. Fifteen enemies were killed before the others abandoned the game. Toward morning a few Japanese rushed in with land-mines strapped to their bellies. Tracer bullets from Garands exploded the mines.

November 8

A typhoon raged over Breakneck Ridge. From the angry immensity of the heavens floods raced in almost horizontal sheets. Palms bent low under the storm, their fronds flattened like streamers of wet silk. Trees crashed to earth. In the expanse of kunai grass the howling of the wind was like a thousandfold plaint of the unburied dead. The trickle of supplies was at a standstill. On Carigara Bay the obscured headlands moaned under the onslaught of the seas. Planes were grounded and ships became hunted things looking for refuge. Massed artillery hurling barrages to the summits of Breakneck Ridge sounded dim and hollow in the tempest. Trails were obliterated by the rain. The sky was black.

Through the typhoon infantry attacked.

At 0700 twelve hundred riflemen launched an assault. They overwhelmed and flowed around enemy positions which a day earlier had refused to yield. Mortar shells drove the Japs out of their emplacements, or deeper into their spider-holes and caves. Bullets and bayonets dealt with Japanese caught in the open. Flame throwers burned those who clung to the caves. “Fox” Company pushed to the southeastern crest of Breakneck Ridge; it dug in on Suicide and Arson Hills. By nightfall it was cut off and surrounded. “Easy” Company pushed up the Ormoc road until its advance was barred by a blasted bridge. Determined Japanese detachments flanked the bridge, and the terrain was dominated by hostile machine guns, mortars and artillery firing from farther ridges. The Jap was at his best. By nightfall, “Easy” Company had been repulsed to its starting point. Over the convulsions of battle pounded the storm.

The Second Battalion[2] struck out to find and capture mysterious Hill 1525. The battle teams left Colasion Point at dawn. All day they marched across trackless mountain country, through gale and driving rain. They met and killed a Japanese officer, and his patrol of ten. The equipment of these Japs was new and of a superior kind; documents found showed the dead to be members of the First Imperial Division. At 4 p.m. the battalion climbed the slopes of a towering height. Around them was a maze of other ridges and interlocking gullies. The jungle was dense and visibility near zero. Further exploration was halted by a force of Japs well equipped with mortars and automatic weapons. In pitch darkness and an eighty-mile wind the battalion dug in on the slopes of what its commander believed to be Hill 1525.

Another battalion under Colonel Spragins[3] toiled toward Hill 1525 to surprise the enemy from the flank. However, at dusk the colonel found that the hilltop he had seized overlooked the Leyte Valley rather than the Ormoc Trail. There lay an intervening ridge a thousand yards to the west. Hill 1525, plain and massive on the map, remained a phantom hidden in rain-filled wilderness.

A fourth battalion[4] was dispatched to the Mount Badian area, flanking the Ormoc Trail to the east, and miles in the rear of the Yamashita Line on Breakneck Ridge. This force fought over mountain paths and by mid-afternoon the column was mired by the typhoon. It did not reach its objective until the following day.

It was a hard day also for the artillery observers. Fogs, rain and jungle made visibility so bad that the observers were forced to crawl to within a hundred yards of enemy positions so that they might direct their shells into the targets. There were occasions when a whole platoon of Japanese combed an acre of jungle to hunt out and kill one hidden artillery observer.

Captain George F. Iwen of Watertown, Wisconsin, was wounded in a forward observation post and encircled by Jap patrols. The Japs did not find him. He remained among them for twenty-four hours, whispering target directions into a portable radio until he collapsed from lack of blood.

Every man in an artillery reconnaissance party on the left flank of Breakneck Ridge was killed or wounded except Sergeant Francis E. Hogg of Springfield, Ohio. Violent Japanese counter attacks were then in progress. Slowly the Americans were pressed back toward the beach. Under mortar fire and aimed snipers’ bullets, Hogg remained in no-man’s-land, radioing information of enemy maneuvers. With his carbine he killed a Japanese who blundered into his foxhole in the soggy kunai. The monstrous force of the wind blew artillery projectiles far off their intended course, and adjustment and correction became a most difficult task. The targets were not stationary. The targets were advancing concentrations of Japanese. At this time a message came to Hogg which told him that all members of an observer’s team on another part of the ridge had been disabled. Their radio, keyed to another battery of field artillery, lay idle. Radioman Hogg decided to retrieve the abandoned radio. Its possession would enable him to serve two batteries at the same time. He leaped out of his foxhole and ran toward the adjoining position. Japanese gunfire killed him.

In the storm a Japanese bomber crashed near the village of Capoocan. Intelligence officers were eager to salvage the crashed bomber’s sights, guns and radio equipment for a study of new wrinkles in enemy armament. But the roads between the coast and the wreck were solidly in Japanese hands. Lieutenant Frank Kennedy of Hinsdale, Illinois, an Air Corps-Infantry liaison officer, volunteered to go. Alone, cutting through jungle, he shot his way to the wreck. Fighting, he stripped the bomber of new ordnance items. A group of snipers a hundred and fifty yards away did their best to kill Frank Kennedy. When bullets failed, they brought mortars to bear. Bursting mortar shells set the wrecked bomber afire. But Kennedy hid the seized equipment in a thicket where it was later recovered. After that he shot his way out and reached a friendly amphibious tank unscathed.

On the windswept hillsides lay the wounded. About them were the torn earth, the mud, the dead, the dripping kunai, explosions, the stench of rottenness, and myriads of insects. Above them were the thunder and the lightning, the black sky, the whining gale and the snarl of bullets. The wounded waited for help. No wounded man was forgotten and left to die on Breakneck Ridge if there was a humanly possible way to save him.

Shortly before noon a company of riflemen working up a slope received machine gun and mortar fire from the crest. Four soldiers were wounded before they could seek cover. Private John Whitley of Iola, Texas, risked his life to crawl to the wounded and to drag them down the slope where aid men were at hand.

When a B.A.R. man crumpled in a fire fight, Private Frank Letzring of Grafton, North Dakota, ran to his aid and bandaged his wounds. A Jap bullet hit Letzring in the leg. But he took over the other’s automatic rifle and helped to repel a Banzai charge. In a later action, while tackling a Japanese machine gun nest, Frank Letzring was killed.

Following the sound of moans in rain and wind, Corpsman Howard R. Cutts, of Chicago, crawled through the kunai. He was unarmed. One bullet creased his helmet; another slugged through his canteen. Cutts crawled on. Near a Japanese strongpoint he found a soldier both of whose legs had been broken by artillery fire. Cutts used the other’s rifle and bayonet as splints. “Now we are ready to move back,” he told the soldier. But the man was unconscious. Cutts began to drag him gently to the rear. But then he gasped and fell sideways. A sniper’s bullet had gone through Aid Man Howard Cutts. He died in an instant.

At the same time “Fox” Company of the Twenty-First lay engaged in the second day of an eleven-day fight for a knob dubbed Arson Hill. They had battled through jungle and on the upper slopes they battled through grass seven feet high. The Japanese were rarely more than ten yards off. In the tall kunai visibility was less than one yard. Men heard bullets zip by in the grass and they could not see a thing. They fired blind volleys to clear the kunai. It was like spraying bullets into a fog. Many were killed or wounded. “Fox” Company lost 35 per cent of its men. In eight days it weathered sixteen Japanese counter attacks. There was an everlasting rain, and when the typhoon blew, it blew in the enemy’s favor. The Japs poured barrels of gasoline on the hillside. Then they set the kunai grass afire.

The tall grass blazed like all hell. A multitude of screeching birds arose to escape the flames. Wounded men cried as they burned to death. There were masses of hissing steam. Wind and rain pressed clouds of smoke close to the ground and the crackling of the burning hillside was louder than the rat-a-tat of machine guns firing from adjoining heights. “Fox” Company’s men fired back through smoke and flames. Some men ran when the fire reached them. Others dug deeper into their holes and let the fire burn over and beyond their holes. All suffered hunger. The company supplies were in a nearby gully, and the jungle-filled gully was infested with snipers. But the fires cleared Arson Hill. After that the shooting was no longer blind.

Out on a flanking patrol to ferret out enemy positions was Sergeant Leroy F. Hanse and two fellow soldiers. Hanse was a farmer from Spencer, Iowa. They circled the hillside in single file, Hanse in the lead. When they found Japs, the Japs were two yards distant. Hanse whipped up his sub-machinegun and fired. He killed six. His companions killed four. The patrol moved on. There was much firing about them from Arisaka rifles. The Japanese were talking to one another in English to confuse and trap the patrol. But the patrol returned intact. The information it brought enabled the company commander to order artillery fire on enemy strongholds.

That night Hanse was on guard near a machine gun on the perimeter. At 10 p.m. he heard a rustling on the charred hillside below. Japs creeping through darkness. There was a slight click as the machine gunner brought his gun into the direction of the rustling. Out of the blackness a voice said in English, “Don’t shoot, buddies— it’s Clem.”

“Clem — hell,” growled Hanse. “Fire.”

At dawn, almost within arm’s reach of the machine gun’s muzzle, they found eleven dead Japanese.

That same night, at 2 A.M., a Jap jumped into Hanse’s foxhole. Hanse hit him in the face with both fists, grappled with him, threw him out. Then he dashed out after the fleeing Jap, overtook him and bashed his brains out with a shovel.

The Division Record summed up this day:

The enemy was stubborn and resisted the advance of all elements. Enemy fire was continuous at the front, flanks and rear of all positions.

November 9

At 4 A.M. the Division’s artillery unleashed a barrage against the ridges on both sides of the Ormoc Trail. To observers it appeared that the explosions left not a square yard of jungle and kunai uncovered. Heavy mortars joined the hard concert at dawn. Punctually at 7 A.M. the guns fell silent. Then fifteen hundred infantrymen arose from the morass of their foxholes to force the ramparts of Breakneck Ridge.

Through quagmire, over fallen trees and up slippery hillsides men panted and fought to break the defense. It was raining hard. The clatter of heavy machine guns supported the attack. Grenades, rifles, bayonets and flamethrowers came into play. Men were running in short, rapid rushes. Men lying in the grass, behind the trunks of trees, in boggy holes, firing. Men threw grenades and on their mud-stained faces were the expressions of bitterness, of a murderous resentment, and of excruciating pain. In battle, words become as scarce as a saint’s curses. Here and there a shout, a warning, a command, a snarl that goes with killing, a roar of utter fear. Some groups were halted by the spiteful chatter of enemy guns. Others pierced through enemy roosts and forged on, slower now, as if the bodies of the slain had added their weight upon the shoulders of the living. There is little a soldier in battle can see; he sees the enemy facing him, and he sees three or four comrades firing and rushing forward at his right or left. But of the outcome of the day’s endeavor he knows nothing until the day is done.

“Item” Company reached the top of Breakneck Ridge at noon; it was cut off and fought for its life. “George” Company took Observation Hill, but was pressed back by a counter assault. “Easy” Company reached its objective, dug in there, and hung on. “Item” Company skirmished in support of “Love,” which at dusk was forced to fall back. In the retreat the company was split.

Private Francis Zines of Red Lake Falls, Minnesota, volunteered to cover the withdrawal. He lay behind a machine gun on the rain-lashed crest and fired. His fire prevented the Japanese from pressing into the rear of his company as it disengaged downhill. Zines was alone, and wounded, but he gave his last so that “Love” Company might live.

A platoon commanded by Sergeant Orian Youngblood of Roswell, New Mexico, was isolated on the central crest of Breakneck Ridge. The crest was shrouded in fog and dusk approached. From above them and from both flanks Japanese assault detachments closed in. Sergeant Youngblood remembered a cardinal rule in any good soldier’s creed: “Never retreat until you receive the order to do so.” But where was his company? It was nowhere in sight. Jap mortar shells came in with malevolent crashing. Jap machine guns hammered an eager tattoo. Their crossfire to the rear of the marooned platoon was designed to cut off the only route of escape. Jap riflemen approached in leaps and bounds. Youngblood heard their hoarse yells. A Jap near enough to toss grenades leaped up in the grass and swung his rifle aloft. Youngblood drilled him between the eyes. Then the sergeant from New Mexico made a decision: give way. There was no gain in letting his comrades die in this manner. He concentrated the fire of his men on the machine guns. As the hostile crossfire wavered and became intermittent, Youngblood led his platoon through the ephemeral gap. He led his platoon along wild ravines and winding stream beds, back through Japanese lines.

That same day the First Battalion of the Twenty-First Regiment slugged its way through to the slopes of mysterious Hill 1525. This force was then ordered by radio to cut through to the Ormoc Trail in the rear of the Yamashita Line. The purpose of this maneuver was to prevent the escape of Japanese troops fighting on Breakneck Ridge.

“Able” Company was left to guard Hill 1525. “Baker” and “Charlie” Companies struck out in the Japanese rear. “Dog” Company, a force of machine gunners and mortarmen, was divided to reinforce the other three. Toward noon the battalion commander radioed that he was within sight of the Ormoc Trail. But a little later came the message that the force was meeting heavy enemy fire; then that it was being attacked by superior numbers of Japanese from the front and both flanks. Two hours later came another report: the force was engaged in a fighting withdrawal in a northwesterly direction.

Meanwhile, on Hill 1525, “Able” Company was attacked from all sides.

Withdrawal is an easy word. But a withdrawal after a day of fighting means that the day’s wounded must be found and carried along in the retreat: helpless men with holes torn by fragments from mortar and artillery shells, men with bullet-lacerated arms and legs, men shot through the face, the belly, the lungs, men with hip-bones smashed or testicles shot away, blinded men, burned men, men with machine gun slugs in both their feet. Litter bearers scrambling over tortuous mountain trails. Machete men in front, hacking away through the thickets. On slippery hillsides, bearers fall and wounded roll into the mud; litters are then passed from hand to hand, down the cruel inclines, up along the sides of canyons, across streams and the carcasses of fallen trees. At times an enemy machine gun cuts loose and everyone lies glued to the ground until the escort of riflemen has found and killed the gunners. At times snipers’ rifles crack in treetops or in the dense kunai. More men are wounded before the snipers can be found and killed. Then the procession moves on — wordless and competent and grim beyond words.

Let it be said to the everlasting honor of our Army that never has a wounded man been knowingly left to die in the jungle. And in that looms the towering summit of men’s unwilling comradeship in war. It is greater than all monuments, greater than the highest mountains, greater than the finest speeches of generals and presidents.

An infantry private named Monroe McGee of Houston, Mississippi, went forward under machine gun fire and dragged a wounded comrade out of blood-stained mud.

An infantry sergeant named David Mumper of Joplin, Missouri, saw a wounded comrade squirming at the base of a tree stump, and he saw a sniper in a treetop fire again to take the wounded man’s life. Mumper dashed forward under the sniper’s sights and carried the soldier down the slope, to safety.

An infantry private named Ara Kaljian of Fowler, California, knew that three wounded soldiers sprawled on a trail would receive more wounds or be killed unless they were moved. Three times he advanced under aimed enemy fire. Each time he dragged one of the fallen men to cover.

Robert Heinig of New Haven, Connecticut, “Dog” Company’s first sergeant, risked death to drag a fellow soldier out of the reach of bursting Japanese grenades.

Corpsman Wilbert Kufhal of Wausau, Wisconsin, crept through enemy lines to save the life of a soldier cut down by bullets while on reconnaissance patrol. The rescued soldier reported that two other members of the patrol lay wounded behind the Japanese lines. They lay at the edge of a dense jungle area on the far slope of the hill, and they were completely surrounded by the Japs.

There was a call for twenty-five volunteers to pierce the enemy front and to bring back the wounded. In less than a minute, twenty-five soldiers volunteered. Leading this rescue force was Lieutenant Edward S. Farmer of Berkeley, California. In a close diamond formation they pushed into the jungle; twenty-six pledging their lives to save the lives of two.

After they had wedged twenty yards through jungle, snipers’ rifles cracked to their left. Bullets zipped through the tangle of vines. The riflemen swung around to challenge the snipers. “Never mind the damn snipers, let’s keep going,” Farmer said. They pushed on and soon there sprang up a stormy clatter to their front. Machine guns fired at the rescue party. Two soldiers sagged into the jungle, wounded. The hammering of a nearby machine gun became continuous. Lieutenant Farmer pulled the pin of a grenade. He plunged through the thickets in the direction of the firing gun. He found the emplacement and he pitched the grenade. The grenade roared and the gun fell silent. The soldiers they had come to rescue were found. Carrying four wounded, the patrol then fought its way back to its own lines.

Sergeant Reinhardt Bock of Tripoli, Iowa, found a wounded comrade from another unit in the path of a Japanese advance. The wounded man was trying to crawl to the rear on elbows and knees, and was hit again. The sergeant halted and picked up the dying man and lugged him toward a ravine. They almost reached cover. Reinhardt Bock died in a burst of Japanese machine gun fire.

In a little clearing mortars thumped in support of foot troops. A Japanese suicide squad dispatched to silence the mortars sneaked in from the flank. Staff Sergeant William Keating of Kansas City, Kansas, led his mortarmen in the repulse of the raiders. The mortars continued their thumping until observers reported that the fighting had shifted to a part of the ridge which could not be reached by the mortars from their present position. Sergeant Keating went forward to find a new position for his mortars. Mortar shells, hurled steeply into the air, need “mast clearance” not easily found in dense jungle. Keating knew that the jungle teemed with snipers — but he was determined to keep his mortars thumping.

He found another clearing, barely thirty feet wide. He ordered his section to move. Concentrated on his task, he did not see two Japanese lurking in the shade of an aranga tree. The Japs fired. Keating leveled his carbine and fired back. One of the snipers threshed the ground. The other dodged behind the tree and continued to fire. Bill Keating died, his face turned toward his men who just then were moving up their weapons to the new position.

The death of their leader did not deflect the mortarmen from their mission. The fighting team carried on. Sergeant Vernon Shipley of Moro, Oregon, sprang into the breach. He got the mortars mounted and he kept them thumping.

The Japanese counter attack on Breakneck Ridge was at its height. Behind a fallen tree on the hillside three soldiers lay in shallow holes. About them shells burst with tearing violence. Bullets struck line-like patterns into the mud. The hillside was alive with Japanese. Close to the left of the three soldiers a friendly machine gun fired in frenzied bursts. The gunner sagged, wounded. The assistant gunner took over the gun. Suddenly three Japanese jumped up six yards away and threw grenades. All three were killed by the machine gun’s spears. But the grenades roared. They killed the wounded gunner and they killed the assistant gunner. An ammunition bearer was hit by fragments. The wounded ammunition bearer now took over the gun. He fired four long bursts before he, too, was killed. The gun was silent.

Behind the fallen tree the three soldiers saw the silent gun. They also saw the Nips rush in, hurling grenades, shouting, shooting from under fixed bayonets. One of three yelled: “Don’t let the bastards get that gun.”

Private John Bresnahen of Detroit, Michigan, crawled toward the unmanned gun. With him came his two companions, Private Dewayne Nixon of Sioux Rapids, Iowa, and Private John Wingertsman of Willimantic, Connecticut. They reached the gun. The enemy understood their intention. Bullets came their way.

The three soldiers clutched the machine gun and dragged it rearward behind the tree. Nixon brought the ammunition. Wingertsman loaded the gun. Bresnahen fired until the barrel steamed in the downpour from the skies. The assault was repulsed.

Sergeant George Smith of Page, North Dakota, chose a name of his own for the height known as Suicide Hill. He called it “Pick-off Hump” because he picked off fourteen Japanese without once changing his position on the hillside.

He had his machine gun mounted at the rim of a half concealed hollow and overlooking a tree-filled canyon. Two hundred yards away and below him a dim trail wound through the under growth. The trail was used by enemy parties carrying ammunition to the front.

Somewhere across this trail lay a huge tree felled by the typhoon. At this spot the Japanese had to leave the hidden path to circle the fallen tree. Sergeant Smith aimed his gun at the base of the fallen tree and waited. Through thirty-six hours he did not move from his position. Every little while a Jap came ducking along the path, and when the Jap circled the tree, Smith unleashed a burst from his machine gun. He was loath to leave the spot after his ammunition had given out. About to depart, he spotted a Jap who was scrambling across the fallen tree. Smith picked up a captured rifle. He dropped the Jap with a single shot.

At nightfall Breakneck Ridge still loomed unconquered. The men who dug their foxholes on the rain-soaked slopes dug with the feeling of castaways forgotten in a cesspool. The battalion which had been sent out to cut the Ormoc Trail in the rear of the Yamashita Line was forced to fall back. A battalion sent out to rescue the surrounded force on Hill 1525 was pressed back 3,500 yards and finally dug in just short of the beach east of Pinamopoan. Another battalion whose mission it was to secure Hill 1525 was delayed by hurricane and morass. They camped in the jungle, but during the night a radio message told them that Hill 1525 had been lost to the Japanese.

November 10

At 7 A.M., through heavy rains, all battalions of the Twenty-First Infantry moved against Breakneck Ridge in a frontal assault. Battalions from the Division’s other regiments fanned out to strike the enemy’s flanks.

By 10 A.M. Observation Hill was captured after two hours of heavy fighting.

An Ormoc Trail bridge three hundred yards east of Observation Hill was stormed an hour later. The bridge was found wrecked beyond use.

By noon Arson and Suicide Hills were in American hands.

At 2 P.M. the battalions gathered for the attack on the remainder of Breakneck Ridge. They thrust forward under cover of gullies and ravines, but on the vile mountainsides they were pressed back to the summits they had attained at noon.

Among “George” Company’s killed and wounded was the company commander. Seymour Smigrod of New York City, a platoon leader, took over. Though wounded himself, he valiantly led his battle team through the day’s fighting.

“Fox” Company on Arson Hill repulsed three suicidal counter attacks. Through fog and smoke the Japanese waves penetrated to within a stone’s throw of the crest. They killed the crew of a machine gun defending the company’s flank. A messenger named William Phipps, of Payette, Idaho, hastened to the threatened spot. He manned the gun and fired. A Jap rose from the mud in front and hurled a grenade. Phipps sat up, shook his head and regained his balance. He crawled back to the gun and fired. Eventually the assault collapsed.

In the confusion of battle a team of automatic rifle gunners were pressed down the slope of the hill. As they fought their way back to the top, one of their number fell wounded. In the midst of heavy firing Private Jancie Castle of Dirchester, Texas, crawled down the slope and saved the soldier’s life.

Corpsman Merle Lemkuhl of Agar, South Dakota, rescued a wounded comrade under fire. Lemkuhl was hit by a bullet as he carried the wounded man to cover. Nevertheless, he rushed out again to give aid to another soldier who cried for help. He calmed the wounded man and then he bandaged his wounds. “All set,” the corpsman shouted through the uproar of the guns. “Relax so I can drag you back.” An instant later Merle Lemkuhl fell mortally wounded.

Leading an isolated platoon of riflemen was Lieutenant Benjamin Rosenblatt of Chicago. Casualties ran high and many of his men suffered from exhaustion. When Rosenblatt received an order to withdraw his group, many of those who had not been hit by bullets or grenades were unable to move. Men lay in the mud, glassy-eyed, beyond all care and all fear of death. In desperation Rosenblatt hastened along the skirmish line, urging, crying, toiling to help his men out of their holes. At the time they did not know that their lieutenant was hit and bleeding. But they rallied. With them they carried their wounded. Ben Rosenblatt was killed in action.

Rations had not reached the front at noon. Ammunition parties were stopped by swarms of snipers constantly crawling through the lines to the American rear. After a platoon leader in quest of ammunition was cut down, Sergeant John Lacy of Wilsboro, New York, assumed command. He solved the scarcity of rounds by collecting ammunition from the dead and wounded. He moved from man to man, distributing the ammunition and with it courage and cheer — “Don’t give up, boys… make ’em count… shoot only at what you can see.”

Every man of a machine gun section commanded by Sergeant Louis Kepler of Deferiet, Missouri, had been killed or wounded — and the Japs pressed in. The last shot had been fired and there was no more. Kepler attempted to drag away the gun. Hostile machine gun fire pinned him down. He was determined that the enemy should not capture his weapon. He took his last grenade and pulled the pin. He placed the grenade under his machine gun and wriggled away, digging a furrow through the slime with both hands. The grenade roared. The gun was destroyed. Kepler then crept back to help the wounded members of his squad to cover.

With “Able” Company, fighting in a canyon at the base of Hill 1525, Private George Diehl of Saint Joseph, Missouri, worked his way through mortar blasts to three wounded men marooned on an exposed bluff. In relays he helped them to reach the protection of the canyon. A radio operator from “George” Company crossed the fire-swept crest of Observation Hill to aid a wounded soldier who was then vainly struggling to stop the escape of blood with a mud-encrusted bandage. The radio operator was Private Frank Shaw, of Sherman, Texas. A bullet struck him while he dragged his buddy to safety.

Toward evening tanks advanced along the Ormoc Trail to take the terrain between the captured heights and the ridges still bitterly defended by the foe. The tanks drew fire from all sides. Their progress was halted by the blasted bridge which had been captured earlier during the day. The bridge originally spanned a deep ravine. The sides of the ravine were too steep to be negotiated by the tracked giants. No by-pass was possible. Intermittent artillery and mortar fire fell on the ravine. Japanese snipers were busy in the walls of vegetation bordering the roadside. Machine guns chattered from a densely wooded ridge immediately in front. The tanks withdrew. “Item” Company’s riflemen, who were dug in around the bridge, promptly found a name for the ravine. They christened it “Dead End Gulch.”

The night around Dead End Gulch was filled with sound and motion. All night the Division’s field artillery and mortars placed interdicting fires in front of the captured heights. Enemy night attacks in force were thus prevented. Private Mario DeMarco, of Chicago, strung a wire line under Japanese gunfire from the battalion command post to the detachments guarding the blasted bridge. Combat engineers went forward to see what could be done about Dead End Gulch.

Engineer Lieutenant Harry R. Hack of San Francisco, and Staff Sergeant Anthony DeMello of Hilo, Hawaii, took the measurements of Dead End Gulch. Hack had been a logger in civilian life. DeMello had been an iceplant mechanic. Since the landings on Red Beach they and their company of engineers had built twelve bridges to make possible the advance of the Division’s motorized strength. To them, this was just bridge job number thirteen.

Hack and DeMello jumped into their jeep. A sign on the jeep bore the legend, “Hardway Construction Co.,” and the added comment, “Silence! Genius at Work.” They drove to a palm plantation two miles to the rear and mobilized their men.

They cut a quantity of palm logs for trestles and stringers. An other crew of soldier-engineers went out to procure a load of heavy planking. A courier was dispatched to Pinamopoan for three boxes of long spikes. Private First Class James Johnson of Helena, Alabama, then trucked the materials through sniper fire to Dead End Gulch.

The firing there was as lively as ever. Muzzle flashes glared intermittently in the night. Rain fell. Curses were muted to whispers. The engineers hauled the logs across the gulch. They worked in knee-deep mud. They built trestles and solid supports. Then they tied palm logs together to a rugged bed of stringers. After that they lugged the heavy planks out over the gulch and nailed them one after another onto the coconut log span. At times the work was interrupted by gusts of firing from the ridge two hundred yards in front. The Japs heard the hammering and they did not like it. By 3 A.M. the bridge was completed. The engineers relaxed in the muck and slept under ponchos, oblivious of the steady thunder of artillery fire falling on Breakneck Ridge.

During the night Japanese patrols cut telephone lines from regimental headquarters to all battalions.

(Continue to Chapter 13: The Breaking of Breakneck Ridge)

______________________________________________

[1] At this time the 19th Infantry Regiment was charged with the defense of the shores of Carigara Bay, the 34th Regiment guarded the Division’s extended and thinly held lines of communication: while the 21st Regiment carried out the frontal attack against Breakneck Ridge.

[2] Second Battalion, Twenty-First Infantry Regiment.

[3] Second Battalion, Nineteenth Infantry Regiment.

[4] Second Battalion, Thirty-Fourth Infantry Regiment.