Editor’s Note: The following account is taken from Historical Tales, by Charles Morris (published 1896).

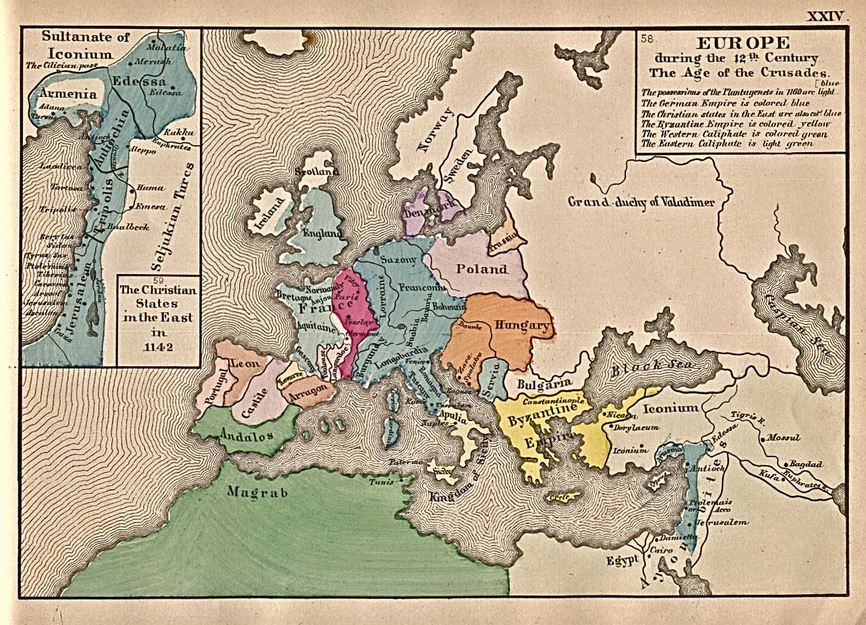

In the month of October, in the year of our Lord 1192, a pirate vessel touched land on the coast of Sclavonia, at the port of Yara. Those were days in which it was not easy to distinguish between pirates and true mariners, either in aspect or avocation, neither being afflicted with much inconvenient honesty, both being hungry for spoil. From this Vessel were landed a number of passengers,—knights, chaplains, and servants,—Crusaders on their way home from the Holy Land, and in need, for their overland journey, of a safe-conduct from the lord of the province.

He who seemed chief among the travellers sent a messenger to the ruler of Yara, to ask for this safe-conduct, and bearing a valuable ruby ring which he was commissioned to offer him as a present. The lord of Yara received this ring, which he gazed upon with eyes of doubt and curiosity. It was too valuable an offer for a small service, and, he had surely heard of this particular ruby before.

“Who are they that have sent thee to ask a free passage of me?” he asked the messenger.

“Some pilgrims returning from Jerusalem,” was the answer.

“And by what names call you these pilgrims?”

“One is called Baldwin de Bethune,” rejoined the messenger. “The other, he who sends you this ring, is named Hugh the merchant.”

The ruler fixed his eyes again upon the ring, which he examined with close attention. He at length replied,—

“You had better have told me the truth, for your ring reveals it. This man’s name is not Hugh, but Richard, king of England. His gift is a royal one, and, since he wished to honor me with it without knowing me, I return it to him, and leave him free to depart. Should I do as duty bids, I would hold him prisoner.”

It was indeed Richard Coeur de Lion, on his way home from the Crusade which he had headed, and in which his arbitrary and imperious temper had made enemies of the rulers of France and Austria, who accompanied him. He had concluded with Saladin a truce of three years, three months, three days, and three hours, and then, disregarding his oath that he would not leave the Holy Land while he had a horse left to feed on, he set sail in haste for home. He had need to, for his brother John was intriguing to seize the throne.

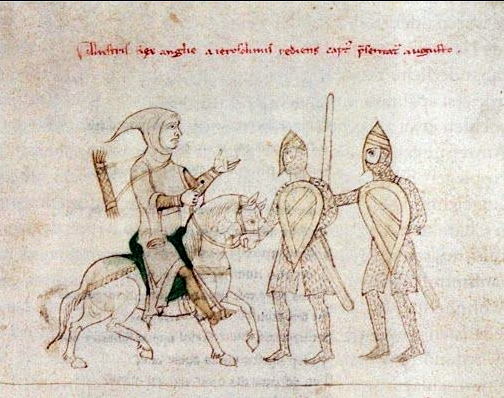

On his way home, finding that he must land and proceed part of the way overland, he dismissed all his suite but a few attendants, fearing to be recognized and detained. The single vessel which he now possessed was attacked by pirates, but the fight, singularly enough, ended in a truce, and was followed by so close a friendship between Richard and the pirate captain that he left his vessel for theirs, and was borne by them to Yara.

The ruler of Yara was a relative of the marquis of Montferrat, whose death in Palestine had without warrant been imputed to Richard’s influence. The king had, therefore, unwittingly revealed himself to an enemy and was in imminent danger of arrest. On receiving the message sent him he set out at once, not caring to linger in so doubtful a neighborhood. No attempt was made to stop him. The lord of Yara was in so far faithful to his word. But he had not promised to keep the king’s secret, and at once sent a message to his brother, lord of s neighboring town, that King Richard of England was in the country, and would probably pass through his town.

There was a chance that he might pass undiscovered; pilgrims from Palestine were numerous; Richard reached the town, where no one knew him, and obtained lodging with one of its householders as Hugh, a merchant from the East.

As it happened, the lord of the town had in his service a Norman named Roger, formerly from Argenton. To him he sent, and asked him if he knew the king of England.

“No; I never saw him,” said Roger.

“But you know his language—the Norman French, there may be some token by which you can recognize him; go seek him in the inns where pilgrims lodge, or elsewhere. He is a prize well worth taking. If you put him in my hands I will give you the government of half my domain”

Roger set out upon his quest, and continued it for several days, first visiting the inns, and then going from house to house of the town, keenly inspecting every stranger. The king was really there, and at last was discovered by the eager searcher. Though in disguise, Roger suspected him. That mighty bulk, those muscular limbs, that imperious face, could belong to none but him who had swept through the Saracen hosts with a battle-axe which no other of the Crusaders could wield. Roger questioned him so closely that the king, after seeking to conceal his identity, was at length forced to reveal who he really was.

“I am not your foe, but your friend,” cried Roger, bursting into tears. “You are in imminent danger here, my liege, and must fly at once. My best horse is at your service. Make your escape, without delay, out of German territory.”

Waiting until he saw the king safely horsed, Roger returned to his master, and told him that the report was a false one. The only Crusader he had found in the town was Baldwin de Bethune, a Norman knight, on his way home from Palestine. The lord, furious at his disappointment, at once had Baldwin arrested and imprisoned. But Richard had escaped.

The flying king hurried onward through the German lands, his only companions now being William de l’Etang, his intimate friend, and a valet who could speak the language of the country, and who acted as their interpreter. For three days and three nights the travellers pursued their course, without food or shelter, not daring to stop or accost any of the inhabitants. At length they arrived at Vienna, completely worn out with hunger and fatigue.

The fugitive king could have sought no more dangerous place of shelter. Vienna was the capitol of Duke Leopold of Austria, whom Richard had mortally offended in Palestine, by tearing down his banner and planting the standard of England in its place. Yet all might have gone well but for the servant, who, while not a traitor, was as dangerous a thing, a fool. He was sent out from the inn to change the gold byzantines of the travellers for Austrian coin, and took occasion to make such display of his money, and assume so dignified and courtier like an air, that the citizens grew suspicious of him and took him before a magistrate to learn who he was. He declared that he was the servant of a rich merchant who was on his way to Vienna, and would be there in three days. This reply quieted the suspicions of the people, and the foolish fellow was released.

In great affright he hastened to the king, told him what had happened, and begged him to leave the town at once. The advice was good, but a three days’ journey without food or shelter called for some repose, and Richard decided to remain some days longer in the town, confident that, if they kept quiet, no further suspicion would arise.

Meanwhile, the news of the incident at Yara had spread through the country and reached Vienna. Duke Leopold heard it with a double sentiment of enmity and avarice. Richard had insulted him; here was a chance for revenge; and the ransom of such a prisoner would enrich his treasury, then, presumably, none too full. Spies and men-at-arms were sent out in search of travellers who might answer to the description of the burly English monarch. For days they traversed the country, but no trace of him could be found. Leopold did not dream that his mortal foe was in his own city, comfortably lodged within a mile of his palace.

Richard’s servant, who had imperilled him before, now succeeded in finishing his work of folly. One day he appeared in the market to purchase provisions, foolishly bearing in his girdle a pair of richly embroidered gloves, such as only great lords wore when in court attire. The fellow was arrested again, and this time, suspicion being increased, was put to the torture. Very little of this sharp discipline sufficed him. He confessed whom he served, and told the magistrate at what inn King Richard might be found.

Within an hour afterwards the inn was surrounded by soldiers of the duke, and Richard, taken by surprise, was forced to surrender. He was brought before the duke, who recognized him at a glance, accosted him with great show of courtesy, with every display of respect ordered him to be taken to prison, where picked soldiers with drawn swords guarded him day and night.

The news that King Richard was a prisoner in an Austrian fortress spread through Europe, and everywhere gave joy to the rulers of the various realms. Brave soldier as he was, he of the lion heart had succeeded in offending all his kingly comrades in the Crusade, and they rejoiced over his captivity as one might over the caging of a captured lion. The emperor called upon his vassal, Duke Leopold, to deliver the prisoner to him, saying that none but an emperor had the right to imprison a king. The duke assented, and the emperor, filled with glee, sent word of his good fortune to the king of France, who returned answer that the news was more agreeable to him than a present of gold or topaz. As for John, the brother of the imprisoned king, he made overtures for an alliance with Philip of France, redoubled his intrigues in England and Normandy, and secretly instigated the emperor to hold on firmly to his royal prize. All Europe seemed to be leagued against the unlucky king, who lay in bondage within the stern walls of a German prison.

And now we feel tempted to leave awhile the domain of sober history, and enter that of romance, which tells one of its prettiest stories about King Richard’s captivity. The story goes that the people of England knew not what had become of their king. That he was held in durance vile somewhere in Germany they had been told, but Germany was a broad land and had many prisons, and none knew which held the lion-hearted king. Before he could be rescued he must be found, and how should this be done?

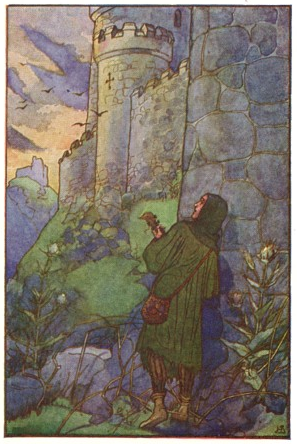

Those were the days of the troubadours, who sang their lively lays not only in Provence but in other lands. Richard himself composed lays and sang them to the harp, and Blondel, a troubadour of renown, was his favorite minstrel, accompanying him wherever he went. This faithful singer mourned bitterly the captivity of his king, and at length, bent on finding him, went wandering through foreign lands, singing under the walls of fortresses and prisons a lay which Richard well knew. Many weary days he wandered without response, almost without hope; yet still faithful Blondel roamed on, heedless of the palaces of the land, seeking only its prisons and strongholds.

At length arrived a day in which, from a fortress window above his head, came an echo of the strain he had just sung. He listened in ecstasy. Those were Norman words; that was a well-known voice; it could be but the captive king.

“O Richard! O my king!” sang the minstrel again, in a song of his own devising.

From above came again the sound of familiar song. Filled with joy, the faithful minstrel sought England’s shores, told the nobles where the king could be found, and made strenuous exertions to obtain his ransom, efforts which were at length crowned with success.

Through the alluring avenues of romance the voice of Blondel still comes to us, singing his signal lay of “O Richard! O my king!” but history has made no record of the pretty tale, and back to history we must turn.

The imprisoned king was placed on trial before the German Diet at Worms, charged with—no one knows what. Whatever the charge, the sentence was that he should pay a ransom of one hundred thousand pounds of silver, and acknowledge himself vassal of the emperor. The latter, a mere formality, was gone through with as much pomp and Ceremony as though it was likely to have any binding force upon English kings. The former, the raising of the money, was more difficult. Two years passed, and still it was not all paid. The royal prisoner, weary of his long captivity, complained bitterly of the neglect of his people and friends, singing his woes in a song composed in the polished dialect of Provence, the land of the troubadours.

“There is no man, however base, whom for want of money I would let lie in a prison cell,” he sang. “I do not say it as a reproach, but I am still a prisoner.”

A part of the ransom at length reached Germany, whose emperor sent a third of it to the duke of Austria as his share of the prize, and consented to the liberation of his captive in the third week after Christmas if he would leave hostages to guarantee the remaining payment.

Richard agreed to everything, glad to escape from prison on any terms. But the news of this agreement spread until it reached the ears of Philip of France and his ally, John. Dread filled their hearts at the tidings. Their plans for seizing on England and Normandy were not yet complete. In great haste Philip sent messengers to the emperor, offering him seventy thousand marks of silver if he would hold his prisoner for one year longer, or, if he preferred, a thousand pounds of silver for each month of captivity. If he would give the prisoner into the custody of Philip and his ally, they would pay a hundred and fifty thousand marks for the prize.

The offer was a tempting one. It dazzled the mind of the emperor, whose ideas of honor were not very deeply planted. But the members of the Diet would not suffer him to break his faith. Their power was great, even over the emperor’s will, and the royal prisoner, after his many weary months of captivity, was set free.

Word of the failure of his plans came quickly to Philip’s knavish ears, and he wrote in haste to his confederate, “the devil is loose; take care of yourself,” an admonition which John was quite likely to obey. His hope of seizing the crown vanished. There remained to meet his placable brother with a show of fraternal loyalty.

But Richard was delayed in his purpose of reaching England, and danger again threatened him. He had been set free near the end of January, 1194. He dared not enter France, and Normandy, then invaded by the French, was not safe for him. His best course was to take ship at a German port and sail for England. But it was the season of storms; he lay a month at Anvers imprecating the weather; meanwhile, avarice overcame both fear and honor in the emperor’s heart, the large sum offered him out weighed the opposition of the lords of the Diet, and he resolved to seize the prisoner again and profit by the French king’s golden bribe.

Fortunately for Richard, the perfidious emperor allowed the secret of his design to get adrift; one of the hostages left in his hands heard of it and found means to warn the king. Richard, at this tidings, stayed not for storm, but at once took passage in the galliot of a Norman trader named Alain Franchemer, narrowly escaping the men-at-arms sent to take him prisoner. Not many days afterwards he landed at the English port of Sandwich, once more a free man and a king.

What followed in Richard’s life we design not to tell, other than the story of his life’s ending with its romantic incidents. The liberated king had not been long on his native soil before he succeeded in securing Normandy against the invading French, building on its borders a powerful fortress, which he called his “Saucy Castle,” and the ruins of whose sturdy walls still remain. Philip was wrathful when he saw its ramparts growing.

“I will take it were its walls of iron,” he declared.

“I would hold it were the walls of butter,” Richard defiantly replied.

It was church land, and the archbishop placed Normandy under an interdict. Richard laughed at his wrath, and persuaded the pope to withdraw the curse. A “rain of blood” fell, which scared his courtiers, but Richard laughed at it as he had at the bishop’s wrath. “Had an angel from heaven bid him abandon his work, he would have answered with a curse,” says one writer.

“How pretty a child is mine, this child of but a year old!” said Richard, gladly, as he saw the walls proudly rise.

He needed money to finish it. His kingdom had been drained to pay his ransom. But a rumor reached him that a treasure had been found at Limousin, twelve knights of gold seated round a golden table, said the story. Richard claimed it. The lord of Limoges refused to surrender it. Richard assailed his castle. It was stubbornly defended. In savage wrath he swore he would hang every soul within its walls.

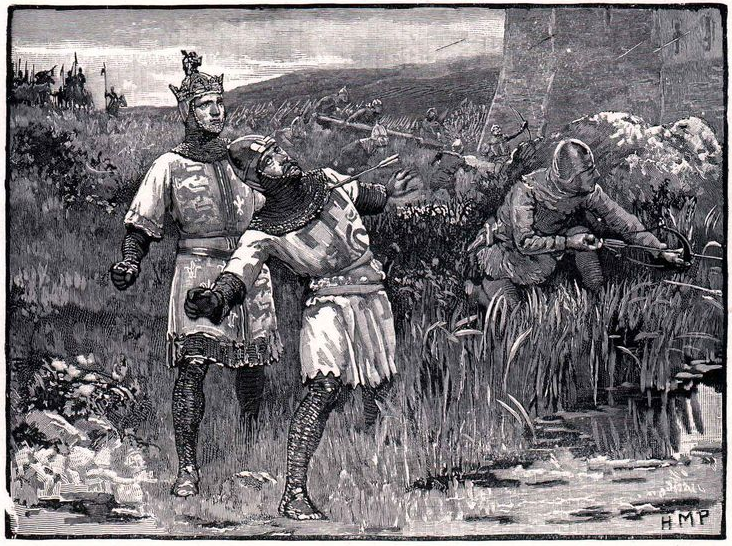

There was an old song which said that an arrow would be made in Limoges by which King Richard would die. The song proved a true prediction. One night, as the king surveyed the walls, a young soldier, Bertrand de Gourdon by name, drew an arrow to its head, and saying, “Now I pray God speed thee well!” let fly.

The shaft struck the king in the left shoulder. The wound might have been healed, but unskilful treatment made it mortal. The castle was taken while Richard lay dying, and every soul in it hanged, as the king had sworn, except Bertrand de Gourdon. He was brought into the king’s tent, heavily chained.

“Knave!” cried Richard, “what have I done to you that you should take my life?”

“You have killed my father and my two brothers,” answered the youth. “You would have hanged me. Let me die now, by any torture you will. My comfort is that no torture to me can save you. You, too, must die; and through me the world is quit of you.”

The king looked at him steadily, and with a gleam of clemency in his eyes.

“Youth,” he said, “I forgive you. Go unhurt.” Then turning to his chief captain, he said, “Take off his chains, give him a hundred shillings, and let him depart.”

He fell back on his couch, and in a few minutes was dead, having signalized his last moments with an act of clemency which had had few counterparts in his life. His clemency was not matched by his piety. The priests who were present at his dying bed exhorted him to repentance and restitution, but he drove them away with bitter mockery, and died as hardened a sinner as he had lived. It should, however, be said that this statement of the character of Richard’s death, given by the historian Green, does not accord with that of Lingard, who says that Richard sent for his confessor and received the sacraments with sentiments of compunction.

As for Bertrand, the chronicles say that he failed to profit by the kindness of the king. A dead monarch’s voice has no weight in the land. The pardoned youth was put to death.

[…] Source link […]

4.5