Peter Thiel says the voters’ bull has a long way to run:

Investor Peter Thiel— who stumped for President Donald Trump at the Republican National Convention and has remained close to the president … is beginning to agree with a colleague on this thesis: “We’re now in a bull market in politics,” he said.

“I’m not sure this is a good thing,” said Thiel. “But it is a fact that maybe politics is becoming more important, it’s becoming more intense, the range of outcomes is becoming greater, and that we’re in a world in which there’s a bull market in politics that’s getting started.”

While I agree that politics are becoming more intense and that the range of possible outcomes is growing, count me as one who thinks those facts imply we are a lot closer to the end of a bull market in politics than the beginning.

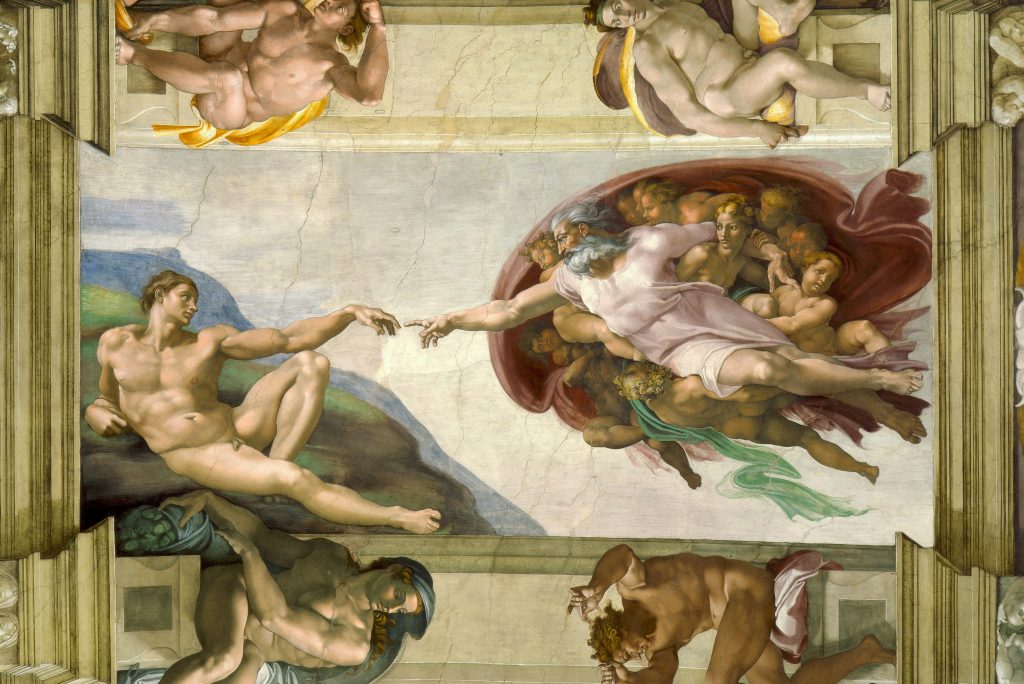

It’s always interesting to watch larval historians come to grips with the ubiquity of religion in the Late Middle Ages. In some ways it’s completely out of their experience. You had mandated feast days and fast days and tithes and special diets and all manner of demands on the people to do this and pay that and go see this and support this vagrant. And few questioned the system’s legitimacy even as they loathed or mocked the corruption of nearly everyone involved in running the system. But then you have them compare it to democracy and the lights come on.

That religious superstructure of authority grew and grew and grew until we reached what might be called “Peak Church” a couple decades before Luther. Finally, it broke out in heresy trials, subjugation, complete economic and social control, and then finally all out war that devastated whole nations. Its peak marked the point where the range of outcomes became greater – i.e. where a break in its steadiness and consistency became evident – and Europe got a few centuries of religious persecutions and wars, and the Pilgrims got Plymouth Rock and the Indians got casinos. Ubiquity marked the end of the bull market in religion and the beginning of a bloody bear.

That religious superstructure of authority grew and grew and grew until we reached what might be called “Peak Church” a couple decades before Luther. Finally, it broke out in heresy trials, subjugation, complete economic and social control, and then finally all out war that devastated whole nations. Its peak marked the point where the range of outcomes became greater – i.e. where a break in its steadiness and consistency became evident – and Europe got a few centuries of religious persecutions and wars, and the Pilgrims got Plymouth Rock and the Indians got casinos. Ubiquity marked the end of the bull market in religion and the beginning of a bloody bear.

Today we find ourselves scratching our heads over how our Catholic next door neighbors would have ever burned us at the stake for not smearing ashes on our foreheads the fortieth day before the first Sunday after the first full moon occurring on or after the March equinox*. I suspect that in a few centuries, people will wonder the same thing about our democratic politics.

Politics in the modern sense – the expectation that we must collectively do something about everything – really got rolling in the Progressive Era of the late 1800s. It was then that we as a nation consciously decided that we were going to mold ourselves and our environment into something new through legal incentive and coercion. We were going to professionalize our barber shops and de-worm the Southrons and civilize the Irish**. We were going to quite forcibly apply the principles of genetic science to society***. We would make children go to approved schools for 186 days a year from the ages of 7 to 16. And we have been growing the beast, tax by tax and regulation by regulation, ever since.

We spend hours every day thinking and talking and arguing about what we ought to collectively do about this problem or that. Though we laugh at the idea that theologians might have argued over how many angels could dance on the head of a pin, today’s computer programmers sit around a lunch table and in all earnest argue about what to do about North Korea’s nuclear weapons****. Unemployed, indebted Millennials sipping $8 lattes from styrofoam cups argue about how to keep the polar ice caps from melting.

Replace ‘tithes’ with ‘taxes’ and ‘priests’ with ‘lobbyists’ and it becomes obvious that our modern society is as saturated with politics as the Middle Ages ever was with religion. Our nation’s richest counties all lie around our national capital. Our companies pay billions of dollars to hire people to beg indulgences, or fund the campaigns of those who can grant them directly. We don’t make pilgrimages to Rome to hear the Pope, but our hairdressers must make annual pilgrimages to the state capital to hear some social work graduate drone on about diversity — which we call continuing education — lest they be legally forbidden to practice their art. Our tithes are legally withheld from our paychecks.

Our government – the voracious product of our politics – has bankrupted our nation, our people, even our money. Still it announces grandiose plans to make us even greater than before using money created from nothing but upon which our children will make perpetual interest payments to those who did nothing to earn them because the law, passed by representatives of the people, says they must.

That sounds a lot like the bell ringing at the top to me.

* The actual calculation of Ash Wednesday. It has nothing on our modern legal requirements for school lunches.

** and use a few dozen poor black men for syphilis experiments.

*** Progressives are understandably loath to claim eugenics as their baby, but in the first third of the 20th century, eugenics was a Progressive idea with intellectual cachet.

**** even as they forget we “did something” about them 20 years ago..

4

4.5

[…] post Calling the Top appeared first on Men Of The […]

An apt comparison. You got chili!

5