Editor’s note: The following comprises the third chapter of Seven Roman Statesmen of the Later Republic, by Sir Charles Oman (published 1902).

III. Caius Gracchus

In studying the career of Tiberius Gracchus we were investigating a very simple phenomenon. The great tribune was aiming at nothing more than the redress of social and economic evils, and had no thought of reconstructing the Roman constitution. When the provisions of that constitution stood in his way, he recklessly overrode them ; but when they chanced to suit his purpose, he utilised their most tiresome and absurd formalities to the utmost limit. It was characteristic of the short sighted Tiberius to press the tribunicial authority to its most exaggerated extension one month, by shutting up the law courts and the treasury, while in the next he struck at the very roots of that authority, and taught men to despise it, by illegally deposing a tribune by the vote of the Comitia. Whether such conduct was likely to strengthen the position of future tribunes, he does not seem for one moment to have reflected. But as a substitute for the old constitution, which he was so ruthlessly breaking up, Tiberius had nothing to put forward. When we examine his programme — the list of reforms that he intended to bring forward in his second tribunate — we find that it does not include any scheme for rearranging the machinery of the state, but only certain proposals to change points of detail, such as the composition of juries, the conditions of military service, and (perhaps) the limits of the franchise. There was no attempt to settle the great problems of sovereignty and imperial administration, which were the really pressing questions of the day. Apparently he was prepared to entrust the unwieldy Public Assembly with the details of the governance of the empire, for which it was even more unfitted than was the oligarchic Senate.

But, in spite of Tiberius’s short-sightedness, the aftereffects of his career were such as to make constitutional changes likely, and even necessary. He had broken up for ever the tacit agreement between Senate and People, by which alone the clumsy machinery of the Roman administration could be kept working. He had shown that the Comitia, if galvanised into activity by a reckless and restless tribune, was capable of reasserting its old theoretical powers, and of passing laws in defiance of the Senate, and in opposition to the Senate’s dearest interests. No state can contain two sovereigns, and it had now to be settled which was really supreme at Rome — the Senate, according to the practice of the last two centuries, or the People, as theory required. It was only necessary that a capable leader should again come forward to put himself at the head of the Democratic party, and then the struggle for sovereignty must force itself to the front as the main problem of the day.

Leaders of a sort were not long wanting, but at first they were mere noisy agitators, who only stirred the surface of things. C. Papirius Carbo and M. Fulvius Flaccus, the immediate successors of the elder Gracchus, were not men of mark or ability. Their doings had little practical importance. Carbo tried to pass a declaratory law, to the effect that tribunes might legally be re-elected year after year [B.C. 131]. He failed, fell away from his Democratic beliefs, and relapsed, for reasons obscure but probably discreditable, into the ranks of the Optimates. A few years later, however, the bill was passed by other hands. Flaccus, who was a genuine enthusiast, but fickle of purpose and lacking in perseverance, began to meddle with another and a much more important question — the enfranchisement of the Italian allies. He brought in a bill for this very just and wise purpose, saw it blocked by the tribunicial veto, and then, instead of persevering with it, suddenly left Rome, and plunged into a series of campaigns in Southern Gaul [B.C. 125]. The Senate deliberately threw the chance of military glory in his way by assigning him the Gallic province ; he could not resist the opportunity, and disappeared from home politics for two years. The only practical result of his agitation was the rebellion of one isolated Italian city, Fregellae, which was crushed with ease by the praetor Opimius [B.C. 125-4].

Ten years passed away from the death of Tiberius, and then there arose a man who knew his own mind, who accurately gauged the problems of the time, and saw that not only the social and economic difficulties of Rome, but also the question of sovereignty must be faced, if the Democratic party was to triumph.

Caius Gracchus was nine years younger than his brother Tiberius, and had been too young to aid him in his schemes, though not too young to be appointed one of the famous triumvirs of the Land Commission — that family party which had given so much offence to the Optimates. When the powers of the Commission were gradually whittled away, and its judicial duties assigned to the consuls (who simply refused to discharge them), Caius sank for a moment into obscurity. But it was not for long; like every other young Roman of good family and active spirit, he put himself in the regular political career, and sued for the quaestorship, as the first step in the cursus honorum. Once started he was bound to go far.

Caius was not a mere enthusiast and humanitarian like his brother: he was a clever, many-sided, wary man, who saw all the dangers of the task he was going to take in hand, and faced them, under the stimulus of ambition and revenge, rather than from benevolence and patriotism. We shall see that all his career was coloured by these motives, a fact which accounts for the many deliberately immoral measures that are to be found in his legislation.

For some years after his brother’s death he took no very prominent part in public affairs; yet he did not keep him self so secluded and obscure as Plutarch makes out. We know, for example, that he made an oration in favour of Carbo’s bill concerning re-election to the tribunate, and that he spoke against the detestable law of Junius Pennus [B.C. 126], which expelled Italian residents from Rome.

Caius took the quaestorship in the year of the law of Pennus, and was sent to serve in Sardinia under the proconsul Aurelius Orestes. He was kept in that unhealthy and uninteresting island for two years, as his office was prolonged for a second term, owing to the jealousy of the Senate, who were glad to keep away from the capital one who bore the dreaded name of Gracchus. Thus, as it chanced, Caius was absent from Italy during the franchise agitation of Fulvius Flaccus and the revolt of Fregellae. This fact did not prevent the Optimates from accusing him of having had a guilty knowledge of the intentions of the rebel city. He won golden opinions for his efficient financial administration in Sardinia, as well as for his personal integrity; he was the only quaestor — as he himself said — who went out with a full purse and came back with an empty one.

After returning from Sardinia in B.C. 124, Caius stood for the tribunate for the ensuing year, and obtained the office without much trouble, so popular was his name among the multitude. The only effect of a bitter opposition to him, started by the Optimates, was that he was returned fourth on the list, instead of at the head of the poll.

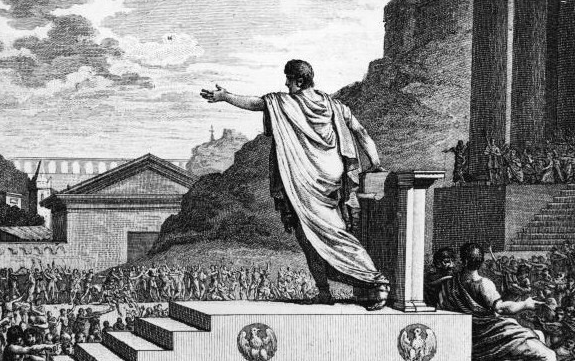

When once launched on the sea of domestic politics, Caius atoned by his unceasing activity for the long delay that he had made before plunging into the troubled waters. He was the most restless and eager of men: beside him, we are told, his brother Tiberius had always appeared mild, moderate, and conciliatory! These are hardly the epithets that we should apply to the author of the confiscation of the domain-land and the deposer of Octavius, but the comparison enables us to understand the terrible vehemence of his younger brother. Caius had no moments of rest or quiet after he had once put himself forward as the friend of the people. His activity was militant and aggressive, his eloquence bitter and vituperative. He was always working himself up into the fine fury that ends in hysterics. We are told that he was aware of the fact, and that when he came down to the Comitia to speak, he stationed a discreet retainer with a pitch-pipe behind him, whose duty was to give a warning note whenever the oration was tending to become a screech. Unfortunately — like the Archbishop of Granada in Lesage’s story — he did not invariably accept the criticism of his underling. He was always on the edge of over-emphasis. First of all Romans, as we read, he strode from one end of the rostra to another while speaking, and cast his toga from off his shoulders by the vehemence of his action. His enemies compared him to Cleon, the blustering demagogue of ancient Athens.

It is strange that a man of such a high-strung nature should have kept back from politics so long. His own explanation of the abstention was that he felt that he was well-nigh the last of his race: save himself and his young son, the male line of the Gracchi had died out, though his father, the consul, had left behind him no less than twelve children. Cicero used to tell a story that Caius had sworn after his brother’s disastrous end to hold aloof from the political life, but that his resolution was broken down by a vision. He thought, as he slept, that Tiberius stood before him, and cried, “Why this long lingering, Caius? There is no alternative. The fates have decreed the same career for each of us — to spend our lives and meet our deaths in vindicating the rights of the Roman people.” Dreams are often the reflection of the subjects on which the mind has been perpetually brooding in the waking hours, and the tale well expresses the blending of motives in the mind of Caius. He felt that it was his duty to avenge his brother, and he was deeply stirred by seeing the Democratic party mute and helpless, for lack of a leader and a programme, when he felt that he could so easily supply both these wants. Ambition and revenge were probably at the bottom of his resolve to a greater measure than he himself was aware.

Whatever was the spark that kindled this eager and susceptible temperament into a flame, there can be no doubt that, from the first moment of his election to the tribunate, Caius displayed the restless energy of a fanatic. He took in hand no less a scheme than the absorption into his own hands of the whole administration, foreign and domestic, of the Roman Empire. His plan was to overrule the Senate by the simple device of keeping perpetual possession of the tribunate, a thing which was now perfectly legal owing to the law which had been passed since his brother’s death. As tribune he would bring in an unending series of laws and decrees dealing directly with all the departments of state, so that the Senate should have no right to meddle with anything. If the sovereign people claimed and used its power to settle every detail of the governance of the empire, there would be no room for senatorial interference. Mommsen has maintained that this scheme was a deliberate anticipation of the monarchy of the Caesars, and that Caius, by proposing to hold perpetual office, as the sole guide and arbiter at whose fiat the assembly should pass laws, was practically intending to make himself tyrant of Rome. This, however, is unfair to Gracchus: it would be more true to say that he aimed at occupying at Rome somewhat the same position that Pericles had once held at Athens. The Athenian had been Strategos year after year, and had guided for half a lifetime the votes of the Ecclesia. Yet no one save comic poets called him a tyrant: he was monarchike tis ischus,[1] as the Greeks phrased it, but that is a very different thing from holding a tyranny. What Caius Gracchus craved was much the same position ; but he had not the calm wisdom of Pericles, and a man of his vehement and reckless temper was certain ere long to fall out with his supporters and wreck his career.

We have said that there was a strong element of revenge among the motives which stirred up Gracchus to put himself at the head of the Democratic party. His two first laws display it very clearly. One of them was a declaratory bill, which re-enacted the old constitutional principle that any magistrate who in his year of office had put to death or banished Roman citizens without a trial should be called to account before the Comitia. This measure was aimed at the Consul Popilius, who, though he had not been concerned in the riot where Tiberius met his end, had subsequently seized and executed many of the reformer’s partisans. The ex-magistrate recognised the intent of the law, and was perfectly conscious of the flagrant illegality of what he had done ten years before, and of the probability of his conviction for high treason. He fled out of Italy into exile, without waiting to be indicted. His fate was well deserved, for the conduct of his party had been abominable; after the death of Tiberius further executions had not been required ; and if they had been, there was no excuse for not proceeding according to proper legal forms of trial.

But the second law of Caius was by no means so righteous. It was aimed at the perfectly respectable and blameless tribune Octavius, who had opposed Tiberius on the question of the Agrarian Law, and had been deposed by him in such an illegal fashion. The bill now brought forward was to the effect that any magistrate whom the Roman people had removed from office, for any cause, was to be for the future incapable of holding office again. This was mere persecution, for Octavius had done nothing more than exercise a right, which he undoubtedly possessed, in a conscientious if somewhat obstinate fashion. All our authorities agree that there was no ground for believing that he had been actuated by spite or corrupt motives. It would appear that Caius found that public opinion was not with him when he attacked Octavius, or that he grew ashamed on second thoughts of this vindictive measure. At any rate, he dropped the bill, announcing that he did so in deference to the wishes of his mother Cornelia, at which (as we are told) the people showed themselves perfectly satisfied.

The other legislative proposals of the first tribunate of Caius Gracchus are of very various kinds, covering all sorts of different spheres of imperial and domestic administration. They plainly show that the vehement young tribune thought nothing too small or too great to be dealt with by the assembly, under his own superintendence as prime minister of the people. It is unfortunate that the historians on whom we have to rely for information do not enable us to make out the exact sequence in which the various laws were passed. We have to deal with them in classes rather than in strict order of time.

In some ways the most important of all was a bill which (in spite of all that the advocates of Caius can allege) appears to have been simply and solely intended to com mend him to the populace, as the true friend who had once and for all filled their stomachs. He proposed a lex frumentaria, which provided that corn — the tithe-corn of the Sicilian cities stored in the granaries of the state — should be sold to any citizen who applied for it at 6 1/3 asses per modius. Each man was allowed to buy five modii a month. In order to prevent swindling and speculation, the buyer had to visit the granary himself and receive the corn in person. Thus the bill profited the urban mob alone, since they were the only citizens who lived near enough to the fount of supply to be able to turn it to account.

Now, 6 1/3 asses per modius was, as it would appear, a rate which represented about one-half the normal price of corn in the Roman market during an average year. The measure was equivalent, therefore, to the free gift of half his daily loaf to every urban voter. The proletariat thought the bill a most admirable one, and its author was hailed, wherever he appeared, as the true friend of the people. He had appealed to them in a manner which even the simplest could understand, and their gratitude reminds us of the famous cry of the Portuguese army when it saluted its commander with the shout, ” Long live Marshal Beresford, who takes care of our bellies.”

The voters of the Suburra were blameless. They knew no better, when they aided their leader to carry through this most unhappy bill. But Caius must bear a very heavy burden of reproach for this miserable bid for popularity. Not only had he devised the surest means of demoralising the urban multitude, but he also dealt the last death-blow to Italian agriculture. More than any other single man, he was responsible for the growth of that mass of paupers asking for nothing but panem et circenses, which in a few generations was to represent the sovereign people of Rome. When once the indigent multitude had begun to expect food from the state at an artificial price, it was not likely that they would stop clamouring till they got it for nothing. The demagogues who pandered to them by continually increasing the dole were the legitimate offspring of Caius Gracchus.

The case against him is made even worse by the fact that at the same moment when he began to distribute the tithe-corn at half-price, he also made a great parade of re-enacting his brother’s Agrarian Law. He declared that the restoration of the old yeoman class was as dear to his heart as it had been to that of Tiberius. He restored the full powers of the Land Commission, for the distribution of what remained of the public domains, and commenced once more to plant out farmers on small allotments.

This was sheer economic lunacy, for how could farming pay in Central Italy, if the state entered the field as a competitor against the local agriculturist, and swamped the Roman market with corn sold at half-price? If Caius really supposed that it was any use to send forth new farmers, at the moment when he was underbidding them by the institution of the corn-dole, he must have been an idiot. If he set the Land Commission to work with a full knowledge that all its efforts must be futile, he must have been a deliberate impostor. Knowing the cleverness of the man, we are forced to conclude that the latter alternative is the nearer to the truth. He probably re-enacted his brother’s law for purely political reasons, not because he thought that it would have any good effect, but because it looked well in the Democratic programme. His real scheme for relieving the economic pressure was of quite a different kind. He intended to despatch the ruined Italian farmers over-seas, to form new colonies in the provinces, where their efforts would not be sterilised by the unnatural condition of the local Roman market.

This was the true way of relieving the distress of the yeoman class: they could not hold their own in Italy without Protection, which it was certain that Caius’s friends in the urban multitude would never grant them. But on the fertile soil of Africa they might do well enough. Accordingly, Caius set his colleague, the tribune Rubrius, to introduce a bill for the founding of a colony on a very large scale — there were to be allotments for no less than 6000 citizens — on the deserted site of ancient Carthage. If the settlers failed to maintain themselves as agriculturists, they would have a good second chance of succeeding as traders, for it was inevitable that some great town must grow up again at a point of the Mediterranean so central and so well suited for maritime traffic. So far Caius was right: within two centuries the restored Carthage was to be one of the greatest cities of the empire, but it was not to call a Gracchus its founder.

Other colonies were to be planted in Italy itself: the places chosen were Tarentum and Capua. These new settlements can never have been intended to live on agriculture; they were clearly designed to become (what each of them had been in the past) great urban centres of trade. The old Capua and Tarentum had not died natural deaths. The one had come to a violent end because it had in the hour of danger deserted Rome during the Hannibalic War. The other, though not quite so harshly treated in a political sense, had been practically ruined by its protracted sieges and the forcible diversion of its commerce to the rival port of Brundisium. Now Capua was an open village without even a legal existence, and Tarentum a decayed fishing-haven. But Caius thought that there was an opening for a great market-town in the midst of the Campanian plain, and for a flourishing port on the Ionian Sea. If strengthened by a draft of Roman citizens, the cities might rise again, if only from the mere convenience of their sites.

For the colonial schemes of Caius, both in Italy and in Africa, we have nothing but praise. He had hit upon the true method of relieving the misery of the proletariat, and if he had been enabled to carry out his designs, there would have been an opening provided for every citizen who was willing to work, and disliked the miserable life of the dole-fed pauper. There are other laws to be placed to his credit which show that when his mind was not warped by revenge or ambition he was a true statesman of the first rank. One was destined to complete the road system of Italy, which had grown up very much at haphazard, and still left many regions practically isolated from the main arteries of communication. Admiring biographers describe to us the excellence of his roads, “drawn in a straight line throughout the country, wonderfully built, with a bed of binding gravel below and a paved chaussée above. When a ravine was met, it was filled up with rubble; when a watercourse, it was spanned by a bridge. Levelled and brought to a perfect parallel, the highroad presented a regular and even elegant prospect for mile after mile. There were pillars of stone to mark the distances and directions, and horse-blocks at convenient spots to enable the traveller to mount with ease.”

Another law that was obviously beneficial, and had been long called for, was one for relieving the rank and file of the army from the burden of providing themselves with clothing. In the old days, when the citizen-soldier spent a few months in the field, at no great distance from his home, and was disbanded at the coming of winter, the custom had been natural and reasonable. But to expect a conscript sent for six years to Spain to keep himself clothed from his modest pay was absurd. Not only was this boon secured to the soldiery, but other laws of Gracchus mitigated the severity of the conscription, securing that no man should be forced to serve before he had attained the legal age, and reducing the number of years for which he could be kept on continuous service. Less happily inspired was another bill, which seems to have given the soldiers at the wars the right to appeal against any sentence of death passed by their general. Such a provision would certainly prove detrimental to discipline. There are occasions when it is absolutely necessary that the commander should be able to punish mutiny or cowardice on the spot by the extreme penalty, and to allow an appeal against him is preposterous. As a matter of fact, the law was not always observed. There are cases known, long after this time, in which military executions took place on the largest scale. Crassus, in the Servile War, once decimated a whole cohort for gross cowardice in the field.

But the most important of all the legislative enactments of Caius Gracchus were those by which he set to work to modify the constitution, by cutting down the powers of the Senate. His chief device for this purpose was to raise up a new corporation in the state, with interests which should be so different from those of the Senate that it might be trusted to act as a check on that body. It was in the Equestrian Order that he found the materials for this counterpoise.

In early days the Equites were simply the cavalry of the Roman army; every man with the “equestrian census,” had to serve as a horse-soldier, whether he were senator, landholder, or capitalist. But by B.C. 123 the Equites had become a very anomalous body. They had practically ceased to have a military organisation; the last occasion on which we hear of them taking the field as a separate corps was at the siege of Numantia. The Roman burgess-cavalry had been entirely superseded by squadrons raised from among the allies. Nor did the Equites any longer number senators in their ranks; since B.C. 129 no senator could be a knight. The body now consisted of those men of wealth who had not been called up to sit in the senate. It was heterogeneous, containing two very different classes of members. The more reputable half of it comprised the larger landowners of non-senatorial rank throughout Roman Italy. The other half was composed of the great capitalists, merchants, and contractors of the city. The urban and the rural knights had few common privileges or functions. The only occasions when they had occasion to meet was when the censor called them up to his quinquennial review, or when the “equestrian centuries” had to give their vote in the Comitia Centuriata. They had very little cohesion or esprit de corps.

Caius resolved to make this wealthy but ill-compacted class into a corporation with common honorary rights and practical advantages. The part of it with which he had mainly to deal was the capitalist class in the city, for just as the urban proletariat, being always on the spot, came to style itself the Roman people, so the speculators and contractors of the capital came to speak of themselves as if they were the whole equestrian body.

The most important of the laws by which Gracchus designed to sow discord between the Senate and the Equites was that by which the control of the law courts was transferred from the one to the other body. Hitherto senators alone were placed upon the album judicum, and allowed to serve as jurymen. The results had been discreditable of late years, and in particular the provincials complained that a senatorial jury would never convict a defaulting governor for embezzlement and oppression. There had been a particularly bad case of the sort just before Caius received the tribunate. M. Aquilius, governor of Asia, had been acquitted, in spite of the fact that the provincials proved against him a number of scandalous acts of mis-government. His acquittal had been secured by wholesale bribery, and the decision had been so iniquitous that the reputation of senatorial juries had sunk to a very low ebb. It was easy, therefore, to attack them on high moral grounds, and Caius’s talent for vituperative eloquence had free scope. His line of argument may be guessed from a fragment of one of his speeches against the Senate which has survived : — “No senator troubles himself about public affairs for nothing,” he observed, “and in the case before us (an arbitration concerning territories in Asia Minor) the honourable gentlemen may be divided into three classes. Those who voted aye have been bribed by one claimant, those who voted no by the other, and those who did not vote at all by both; and these last are the most cunning of all, for they have persuaded each party that they abstained in his interest, saying that if they had voted at all, they must have done so for the other side.”

The senatorial juries had undoubtedly been most unsatisfactory. But the equestrian juries which Caius substituted for them were even worse: there is no reason to believe that the tribune was unaware of this fact, for in reference to this law he is recorded to have remarked that “he had cast daggers into the Forum with which the two orders should lacerate each other.” Clearly his purpose was to brew mischief for the benefit of the Senate, rather than to secure any advantage for the citizens or the provincials. To put the control of the law courts into the hands of the urban knights (for the rural knights did not count) had the worst possible effect. The typical eques was a good deal more of a money-lender, speculator, and financial agent than of a mere merchant. His interests were as much opposed to those of the provincials as they were to those of the Senate. His main wish was to exploit the empire for the benefit of his own class. It is difficult to construct any parallel from modern times which can bring home to the reader the exact meaning of the surrender of justice into the hands of the Equites. Some faint adumbration of the results may be realised by imagining what might happen in England if all juries had to be chosen exclusively from members of the Stock Exchange. Whenever any financial question might be in dispute, there would be a tendency, even in honest men, to decide in favour of their own class interests. The Roman publicanus was little influenced either by delicacy or by regard for public opinion. The result of giving him judicial omnipotence was merely that he abused it for his own interest rather more than his senatorial predecessors had done. “The Equites,” says Appian, “soon adopted the senators’ system of bribery, and no sooner had they experienced the pleasures of unlimited gains, than they proceeded to strive after them far more shamelessly than had ever been done before. They used to set up suborned accusers against the senators; they not merely tyrannised over them in the law courts, but openly insulted them.” The old grievance had been that bad provincial governors escaped punishment for their misdeeds, owing to the misplaced tenderness of their friends on the jury. The new grievance was that any one who did not play into the hands of the Equites, and grant them whatever they asked, was prosecuted and condemned, however blameless his conduct might have been. It took some years for the system of blackmailing to reach its perfection, but what it grew to may be judged from the case of Rutilius Rufus. This virtuous administrator had set himself to protect the provincials of Asia from the extortions of the publicani. He came home bringing with him the blessings of the whole land; but on his return the financiers had him accused (of all things in the world) of embezzlement and extortion. He was promptly condemned, though he brought representatives of every class of the provincials to bear witness that he was the best friend they had ever known: and retired to live in honoured exile among the very people whom he was supposed to have oppressed.

Doubtless Caius did not foresee the full harvest of scandals which was destined to spring up from his treatment of the law courts. But he must have known that he was putting power into the hands of a class that could not be trusted. For the results, therefore, he must take the responsibility. Meanwhile he obtained the immediate profit that he had desired: “the Equites supported the tribune when votes were required, and received from him in return whatever they wished.”

How harmful to the state were these “things which they wished” may be seen from the case of the Asiatic taxes. Since their annexation in B.C. 133, or rather since their rescue from the hands of the rebel Aristonicus in B.C. 129, the cities of Asia had been paying to Rome a fixed tribute of moderate amount. But the knights loved the system of tax-farming, and suggested to Caius that it might be introduced into this wealthiest of all the provinces. He consented, and by his law de Provincia Asia censoribus locanda instituted a most detestable form of it. Not only was the tithe system imposed on Asia, and the administration of it farmed out, but it was ordained that the bidding for the tithes should take place before the censors at Rome — not at Pergamus or Ephesus — and that the whole revenue of the province should be contracted for en bloc. The object of this strange arrangement was that provincial competition for the contracts might be excluded, firstly, by the fact that the auction was held in Italy, and, secondly, by the enormous capital required. For only a syndicate of Roman millionaires could afford to contemplate the tremendous sums that had to be dealt with, when the land revenues of the whole of the two hundred cities of Asia were handled in a single contract.

By means of Caius’s law the old kingdom of Pergamus, the last region of the Hellenic East which had preserved its prosperity, was reduced in a single generation to a deplorable state of misery. The best commentary on the new system of government is that when, in the year B.C. 88, a foreign enemy entered Asia, the whole countryside rose like one man in his favour, and massacred in a single day the 80,000 Roman traders, officials, and tax-collectors who dwelt among them.

The great tribune was re-elected for a second term of office without any difficulty, and his work in B.C. 122 was a continuation of that of the previous twelve months. Several of the laws of which we have already spoken only came to full fruition in the latter year. Caius was now thoroughly well established in power as the people’s prime minister : he was commencing to add a whole bundle of standing offices to his main title of tribune, being triumvir on the agrarian board, chief commissioner of roads, and official superintendent of the new colonies that were to be founded. Plutarch, speaking in a somewhat exaggerated strain, asserts that he was occupying a quasi-royal position, that he had prostatis ton dimon.[2] But he forgets to point out that he was destitute of one most important element of power — he had no regular armed force at his back, only the fickle bands of the urban multitude. The Roman constitution, as time was to show, could only be overthrown by an imperator with legions at his heels: the orator, who had but his ready tongue and his chance mob of partisans, was really unequal to the task of up setting the old regime. But meanwhile his power and activity were very terrifying to the Senate. “Those who most feared the man were struck with his amazing industry, and the facility with which he despatched the most diverse kinds of business.” He lived in the centre of a sort of court, frequented equally by foreign ambassadors, architects, engineers, military men, and philosophers. He had business with all these classes, received them all with urbanity, and surprised them all by his interest in and mastery of their various provinces of knowledge. It was easy for his enemies to say that there was a royal court already established in Rome, with nothing wanting save the diadem.

During his second tribunate Caius was engaged both in completing his legislation in behalf of the Equites and in developing his great colonial schemes, especially that for the establishing of the new city that was to be called Junonia, on the site of Carthage. But he was also launching out on to the development of another item of the Democratic programme: he wished to carry out that liberal extension of the citizenship to the Italian allies which had been growing more and more of a necessity during the last fifty years. Tiberius Gracchus, if we may trust Velleius, had broached the idea in B.C. 133: Fulvius Flaccus had certainly brought it to the front in B.C. 125, with no result save the unfortunate revolt of Fregellae. But Caius had much more favourable opportunities than either his brother or Flaccus, for he had secured a much more complete hold over the Comitia than either of them had ever possessed.

The project was one which was eminently deserving of support. In former days the Roman people had been fairly generous with the franchise; not only had all the Latin and Etruscan districts around the city been granted the full citizenship one after another, but there were ways provided in which individual members of allied states further afield might become incorporated in the body of Roman burgesses. But this wise liberality had gradually gone out of fashion. Just as Roman citizenship grew more and more valuable, owing to the ever-increasing profits of empire, it became more and more difficult to obtain. No new territory in Latium or Etruria had been taken into the state boundary since B.C. 188, and it was growing much harder for the individual citizen of an allied community to slip into the burgess body. The fact was that the Romans in ancient days, when fighting for existence, had been eager to strengthen themselves by multiplying their numbers: now that they had acquired an empire, they were less eager to share their advantages with others. The knowledge that discontent at their niggardliness was ever growing more lively among the Italian states, had not yet begun to alarm the ordinary Roman, whether Optimate or Democrat. The city rabble were just as unconcerned about it as the most purblind reactionary in the Senate.

Caius Gracchus, therefore, had to convert his own party to the policy of liberal treatment for the allies. It was true that his brother may have advocated their cause, and that others among the leaders of the party, notably the energetic but unstable Fulvius Flaccus, were convinced of its righteousness. But the weapon with which Caius had to win his victories was the urban multitude, the one constant element in the composition of the Comitia. He thought that he could carry it with him, even when he was advocating measures which were not directly and obviously profitable to itself. Indeed, he imagined that he had bought it for ever, belly and soul, by the gift of the corn-dole. He was so far right that a great portion of the populace was ready to stick to him through thick and thin, and to vote for whatever bill he might chose to bring forward. Unfortunately for himself and for Rome, he was to discover that the whole body was not so loyal, and that men who could be bribed once to vote for the Democratic side, might be influenced on another occasion by equally corrupt inducements held out by the enemy. Caius was always styling the urban multitude “the people.” He was destined to find that it might be truer to call it “the rabble.”

The very moderate and statesmanlike form in which Caius proposed to deal with the franchise question was to bestow the full citizenship on the Latins, and the rights hitherto held by the Latins on the remainder of the Italian allies. The “Latins” now represented not the old thirty cities of the Latin League, which had long been taken into the Roman state, but the numerous colonies with “Latin rights,” i.e. the jus connubii and jus commercii, which were scattered all over Italy. They only wanted the power to vote in the Comitia to make them full citizens; the practical as opposed to the political advantages of the status were already in their possession. On the other hand, the main body of the Italian allies were to receive the commercial and civil privileges hitherto confined to the Latins, but were not to be introduced into the tribes, or permitted to swamp the public assembly by their enormous numbers. No doubt Caius contemplated the arrival of the day when they too might become Romans. But he had no wish to hurry matters, and intended to bring about the complete Romanisation of Italy by gradual emancipation; only after a longer or shorter training as Latins would the multitudes of Central and Southern Italy be permitted to obtain the full franchise.

All this was prudent, moderate, and far-sighted; but unfortunately there was little in the scheme to rouse enthusiasm among the more sordid members of the Democratic party — the mass of demoralised urban voters who formed the habitual majority in ordinary meetings of the Comitia. In their ignorant selfishness, they looked upon the matter from a very narrow point of view. The individual Roman citizen, they thought, would suffer if the number of his equals were increased. There would be more hands among which the bribes of the would-be consul and praetor, and the public distribution of money and food made by the state, would have to be divided. The Consul Fannius, though he had been elected by the assistance of Gracchus himself, led the opposition. He put the question in a nutshell when he asked the multitude whether they had reflected that by passing such a bill they would soon have the Latins elbowing them out of their places in the Comitia, crowding them out of the circus and theatre, and eating up their corn. This sordid and cynical appeal went to the heart of the plebeians, and the majority of them soon showed that they were ready to refuse support in this matter to the leader who vainly believed that he had purchased their perpetual allegiance.

While the franchise question was still in an early stage, a new figure appeared upon the scene, to the great perplexity of Gracchus. This was a certain Marcus Livius Drusus, a tribune of whom little had hitherto been known. He did not attempt to resist Caius by the method of mere stolid opposition, which Octavius had used ten years before against the reformer’s elder brother. His plan was one which had often been tried in Greek politics. The counter-demagogue had been a well-known figure at Athens, though he was as yet unfamiliar at Rome. Drusus professed to be even more devoted to the people than his colleague, and to be ready to go yet farther in the paths of innovation. Only on two questions — that of the founding of colonies beyond the sea, and that of granting the franchise to the Italians — did he profess to differ from him. Of both these measures he disapproved, but he had his own substitutes ready, both for propitiating the allies and for providing land for the would-be colonists.

With the object, then, of showing that he was a truer and more liberal friend of the people than Caius himself, Livius Drusus announced his intention of bringing forward a whole series of popular measures. Perhaps the most prominent of these was a huge scheme for colonisation inside Italy. Instead of choosing only two places with particularly favourable sites, as Gracchus had done, he announced that he would establish no less than twelve colonies in the peninsula, each of them to hold no less than three thousand citizens. The scheme was wholly impracticable, for these were to be agricultural and not trading centres, and agriculture, as we have already seen, was ruined beyond redemption. But the populace had not yet grasped the fact, and the plan seemed to them far more attractive than anything that Caius had proposed. Equally popular and equally futile was another bill, which was to turn all the farms which had already been distributed by the Land Commission into the private property of their occupiers. Tiberius Gracchus had made a great point of imposing a rent upon them, in order to remind the farmers that they were the tenants of the state and not full freeholders. He had also prohibited them from selling their land, for he had feared that they would be prone to dispose of their holdings at the first bad season, if they were given the chance, so that the latifundia would in a short time be reconstituted. It is probable that ten years of unprofitable farming had already disgusted great numbers of the settlers of B.C. 133-132, and that they were now wishing to throw up the holdings for which they had once clamoured so loudly. At any rate, there is no doubt that Drusus’s proposal to make the land alienable, and to abolish the modest rent imposed by Tiberius, acquired a certain cheap popularity. There were other bills brought forward at the same time of which we have no accurate details. One was intended to propitiate the allies for being refused the franchise; it provided that Latin soldiers should no longer be liable to the punishment of scourging by Roman officers — and probably their status in other ways was to be brought nearer to that of their comrades who possessed the full citizenship.

In proposing each of his laws, Drusus took great care to point out to the people that he was acting with the full consent and approbation of the Senate. He wished to produce the impression that popular legislation could be procured from other sources than the Democratic party, and succeeded in his aim. The majority of the urban multitude were too stupid to see that when the competition was ended by the removal or death of Gracchus, their noble friends would relapse into their former state of apathy as to the needs of the people. It has been suggested by some historians that Drusus was not a deliberate charlatan playing a part, but a real, though misguided, enthusiast, who was unconsciously made the tool of the Senate. It has been pointed out that several of the laws which he proposed in B.C. 122 were reintroduced a generation later by his son, who was a genuine Democrat of the most enthusiastic sort; and it is suggested that the elder Drusus believed in his own panacea, and passed it on as a sacred secret to his son and heir. But on the whole it is safer to believe the Roman historians when they tell us that the colleague of Gracchus was well aware of what he was doing, and had no more worthy aim than to undermine his rival’s position by out-bidding him in the market of popular favour.

The waning power of Caius over the multitude was shown most clearly by the fate of his bill for the enfranchisement of the Latins. When it was brought forward, Drusus announced that he should veto it. There was no explosion of popular wrath, for the fact was that the majority of the multitude was apathetic on the point, or even held that the good things of empire had better be distributed among a few than among many Roman citizens. Caius saw no opportunity of assailing his colleague; he made no attempt to demolish him, as his brother of old had demolished Octavius; public feeling would have been against him if he had tried. Instead of starting a furious agitation on behalf of the Italians, as his friend and colleague Fulvius Flaccus proposed, he went off to Africa to superintend the foundation of his new colony of Junonia. Thus the Democratic party in the city was left in the temporary charge of Flaccus; this was unfortunate, for the ex-consul was a man equally devoid of tact and of prudence, and prone to plunge into profitless violence when freed from the restraints imposed by his more statesman-like friend.

Caius probably supposed that nothing would commend him more surely to the people than the sight of the new Carthaginian colony inaugurated with all possible pomp and splendour, and flourishing from the first, as it was bound to do, if only it obtained a fair start. He marked out the site on an even larger scale than the Rubrian law had named, and made a great parade of assembling colonists from all over Italy, apparently permitting Latins as well as Romans to send in their names. All the proper ceremonies were carried out: the flag was planted, the furrow driven round an enormous space of ground, and the boundary stones set up.

When, however, Gracchus returned from Africa to Rome, he found that his demonstration had completely missed fire. The most absurd rumours had been put about by his opponents: a legend had cropped up that Scipio had solemnly cursed the site of Carthage when he captured it in B.C. 146, and that nothing could prosper on such unlucky ground. It was said that a gale had torn down the standard which Gracchus had erected — a fact quite possible in itself, but rendered less likely by the additional garnishment of the story, which said that the boundary stones of the new colony had been dug up at night by wolves. If wolves there were, they must clearly have been two-legged Roman wolves of the Optimate breed. Nevertheless these silly tales seem to have had their effect, and to have loosened the hold of Caius on the Comitia. When the tribunicial elections came on, and he stood for the third time, he failed to be chosen. It is said that he had really a majority of votes, but that Drusus or some other tribune who presided at the poll made a fraudulent and unjust return. That such a thing should have been possible shows that at least the suffrages of the people must have been much divided, for if Caius had possessed his former ascendency, no one would have dared to juggle with the votes.

Gracchus was appalled with this misadventure. “He bore the disappointment with great impatience, and when he saw his adversaries laughing, told them with an air of insolence that they should soon be laughing on the wrong side of their mouths.” Meanwhile he had only a short time left in which the invaluable tribunicial position was still his own: on the 10th of December B.C. 122, he would become a private person again, and would not only lose his power of legislation, but become liable to prosecution for any illegal acts which his enemies might choose to allege against him. The last months of his office seem to have been spent in a bitter personal struggle with Drusus. Each produced strings of popular laws to tempt the appetite of the people, and Caius had the disappointment of seeing himself outbid by a rival whose main advantage was that he was prepared to bring forward projects, possible or impossible, with no thought of the consequences. As a good Greek scholar, Gracchus must have recognised that he had fallen into the unenviable position of Cleon in the Knights of Aristophanes. His stewardship was about to be taken from him, and he would soon be obliged to give an account of all his doings.

At last the fatal day came round, and Caius ceased to be the sacrosanct representative of the Roman people, and became once more a private citizen. It is probable that, even if he had kept quiet, his adversaries would now have found some excuse for falling upon him: like his brother Tiberius twelve years before, he had made too many enemies. But he did not give them the opportunity of leaving him alone; within a few days of the coming of the new year, B.C. 121, he was engaged in bitter civil strife with them. For he had still plenty of partisans at his back: the better men of the Democratic party still believed in him, and among the multitude there were many whose profound hatred for the Senate and all its works had led them to distrust the gifts of Drusus. Most important of all, there was a lively agitation outside Rome: the Latins were bitterly vexed that the citizenship, which had been dangled before them for the second time, had now been again withdrawn from their reach. Their old friend, Pulvius Maccus, got into communication with them, and assured them that he had not forgotten them, and still hoped to defend their cause. But organisation was needed to bring their forces to bear, and of organising power there seems to have been little or none on the Democratic side.

The moment that the new magistrates of B.C. 121 were installed in office, an effort was made by the Optimates to rescind as much as they dared of the Gracchan legislation. The Equites were too strong to be lightly meddled with, and the laws passed in their favour were left alone. It was still necessary to keep the urban multitude divided, so no attempt was made to touch the corn-dole. Any hint of such a design would have thrown the whole mass back into the arms of Gracchus. It was accordingly against the colonial scheme that the Optimates opened their batteries. Formal representations were made to the augurs that the omens at the foundation of Junonia had been unfavourable, and all the stories about the gale, the broken flag-staff, and the uprooted boundary stones, were brought forward. The augurs made the reply that was required: “The auspices of Junonia had been most unfavourable, and clearly showed the anger of the gods at the unhallowed attempt to build upon the cursed soil.” Accordingly the Consul Opimius, who assumed the lead in all the proceedings against Gracchus, took the opinion of the Senate on the question whether it would not be right to annul the Rubrian law and disestablish the new colony. The Fathers fell in with his design, and granted him an auctoritas for the introduction of an act of repeal. It was accordingly brought before the people by the tribune, M. Minucius.

This brought Caius to the front. The scheme for transmarine colonisation was very dear to him. In it, as he believed, lay the true remedy for the economic distress of the Roman people. “When Gracchus and Fulvius Flaccus,” says Appian, “discerned that their great project was to be thwarted, they became like madmen, and ran about declaring that all the stories about the evil omens were lies invented by the Senate.” They announced their intention of opposing the Act of Repeal by every means in their power, and began, when it was too late, to organise their partisans for the fray. This was precisely what their enemies had hoped. If they could be goaded into any act of violence, they could be accused of treason, and doomed to suffer the same lot that had fallen on Tiberius Gracchus and his followers twelve years before. Neither party made any attempt to disguise their intention of using force if it should become necessary. The Optimates secretly armed their clients and slaves. On the other hand, Flaccus sent the word round rural Italy that strong arms were needed at Rome. It is said that hundreds of his partisans, disguised as labourers, came up to the city on the day when the Bill was to be brought forward, and that there were more allies than citizens among these able-bodied visitors. Caius appears to have disliked this open appeal to violence. He felt that the Democrats would be putting themselves in the wrong if they began the fray, and seems to have discouraged his followers by his fervid appeals to them not to take the offensive. But the die was cast. The more enthusiastic Democrats were determined to fight, and came down to the assembly armed with daggers and staves as if a conflict was absolutely certain. They were so far right, and their leader so far wrong, that in the present strained situation of affairs there was no hope of a peaceful issue.

On the day of voting the Optimates and the Democrats faced each other more like two armies than two orderly political factions. On each side the lethal weapons were barely disguised beneath the broad folds of the togas. The only doubt was whether the enemies or the partisans of Gracchus would strike the first blow. As a matter of fact, the Democrats put themselves in the wrong by opening the battle by a wanton murder.

The Consul Opimius had opened the proceedings by the usual sacrifice in the porch of the Capitoline temple. When he had done, one of his servants — a certain Q. Antullius — who was carrying away the entrails of the victim, rudely pushed through the front rank of the Democrats, crying, “Stand off, ye bad citizens, and make way for honest men.” It is said that he emphasised his insulting words by making a gesture of contempt in the very face of Gracchus. At this Caius gave him a fierce look, whereupon an over-zealous follower stepped forward and stabbed the man through and through with a dagger. Antullius fell dead between the two parties, with the sacred entrails still in his hand.

Prepared for strife as all those present had been, they were yet shocked by this sacrilegious murder. No melee followed, but the enemies stood gazing upon each other, and no one dared to strike a second blow. At this moment a sudden thunderstorm burst over the Capitol, and, awed by the manifest wrath of Jupiter, the whole armed multitude melted homeward in the drenching rain.

The day ended without the expected battle, but blood had been shed, and the Optimates were able to cast the responsibility for the commencement of civil strife upon their adversaries. It is certain that if Antullius had been left alone, the contest would merely have broken out a few minutes later, for both crowds were bent on mischief, and the most trivial incident would have sufficed to set them by the ears. Morally speaking, the guilt may be equally divided between them, for each had come down prepared to fight, and if the Democrats had not struck the first blow, the Optimates would have done so a little later. Both the Consul Opimius and the headstrong Fulvius Flaccus had deliberately got ready for battle, and whatever may have been the private feelings of Caius, it is certain that he came down armed to support his friends. His admirers have alleged that he was precipitated into civil war against his will; his detractors have quite as much to say for their view when they assert that he lost his opportunity for carrying out a coup d’etat because a reckless fool struck too soon, and placed his whole party at a moral disadvantage.

There can be no doubt that the dagger-thrust dealt by this over-zealous Democrat ruined his party. It was to little purpose that Caius went down to the Forum that same afternoon, and tried to explain away what had happened as a deplorable accident, for which he was not responsible. Many who might otherwise have supported him had been profoundly shocked, and it is impossible for the man who has placed himself at the head of an armed mob to disavow any connection with its atrocities. Just as Robert Emmett was responsible for the murder of Lord Kilwarden, though he may not himself have thrust a pike into the old judge, so was Caius Gracchus responsible for the murder of Antullius. It is useless in such cases to plead blameless character and patriotic intentions. Moreover, the friends of Caius did not even take the trouble to excuse themselves. Fulvius Flaccus, when the assembly had broken up, called together a mob of his supporters, harangued them, and armed them with a store of weapons which lay in his house, for he possessed a complete arsenal of Gallic broadswords and lances, the trophies of his successful campaign of B.C. 125. He and his reckless satellites passed the night in noise, riot, and carousing; the ex-consul himself, it is said, was the first man drunk, and in his cups uttered many obiter dicta most unbecoming in one who was about to plunge the city into war next morning. The behaviour of Caius was very different; he burst into tears on leaving the Forum and shut himself up in his room, gloomily pondering over the end to which two years of civic power had brought him. But though he did not commit himself to any overt course of action, a great mob of his partisans gathered round his house, and encamped about it all night. Another mass collected in the Capitol before dawn, to occupy the points of vantage for the struggle which was expected to break out in the morning.

Meanwhile Opimius and the other foes of the Democratic party had been making much more practical preparations. The consul had ordered every senator and every knight of the Optimate party to provide two fully armed men; he had taken command of a body of Cretan mercenaries who chanced to be passing through the city, and had ordered a general muster of the clients and retainers of his friends. They were a formidable band, and, with the magistrates at their head, they had the inestimable advantage of appearing to represent law and order.

Protected by this mass of special constables the Senate met next morning. The consul began to lay before them the desperate state of affairs, and the necessity for outlawing the Democratic leaders. At this moment, by a preconcerted arrangement, the bier of Antullius, followed by his mourning friends, was borne past the doors of the Senate-house. The Fathers rushed out and burst forth into exaggerated demonstrations of horror and sympathy. Then flocking back to their seats they passed the senatus consultum ultimum, which empowered the consuls, in the usual terms, “to take care that the republic might receive no harm.” Rome was thus put under martial law, and as a last formality messengers were sent to Gracchus and to Fulvius Flaccus, bidding them repair in person to the Curia in order to give an account of their doings.

Frightened at the great armed force around the Senate-house, the Democrats had begun to concentrate on the Aventine. They were almost destitute of guidance, for Caius was sunk in a melancholy apathy, and Flaccus was barely recovered from the effects of last night’s debauch; it was with difficulty that he could be roused at all that morning. The only intention displayed was to stand at bay on the old plebeian stronghold; no offensive action seems even to have been contemplated. But the temple of Diana and the neighbouring streets were barricaded, and emissaries ran round the city calling the multitude to arms, and even promising freedom to any slaves who should join them. This last anarchic proposal must have disposed of any chance that Caius might gain support among his old allies of the equestrian order. The very name of a slave-rising was enough to make an Optimate of every man of independent means.

It was probably the perception of the fact that the number of their partisans on the Aventine was much smaller than they had expected, which led the Democratic leaders to negotiate before opening hostilities. When they received the message from the Senate, which bade them come down and justify their actions, Caius, it is said, seriously proposed to take his life in his hands and obey the summons. But Flaccus objected to put himself in the power of the enemy. He would only consent to send his son Quintus with a reply, in which the garrison of the Aventine offered to lay down its arms and disperse, if a complete amnesty was offered to every citizen, small or great. It is said that many of the senators were not indisposed to accept these terms: except to fanatics, anything is better than civil war. But Opimius carried a majority with him when he declared that traitors could not send ambassadors, but should come in person to surrender themselves to justice before they sued for mercy. The young Flaccus was sent back to his father, and told not to come again, unless he brought with him an offer of unconditional surrender.

After some futile debating between the leaders of the Democrats, the proposal to capitulate without terms was negatived, and the son of Flaccus was once more despatched to the Senate with a second set of offers. Opimius told him that he had been warned not to return, and that he had forfeited any claims to be considered an ambassador. He cast the young man into prison, and ordered his armed bands to converge upon the Aventine. Then he published a notice that any one who laid down his arms before fighting began should be granted an amnesty, but that Gracchus and Fulvius were public enemies, and that whoever brought their heads to the consuls should be paid for them their actual weight in gold.

The rumour of this proclamation, and the sight of the Optimate bands working upwards among the streets that lead to the summit of the Aventine, was too much for the resolution of most of the Democrats. A great many slunk off to their houses while yet it was time. But enough remained to defend the barricades, and for some little space there was sharp fighting between the two parties. But the Cretan archers so galled the Democrats that ere long they gave back from their position, and the assailants stormed the hill-top and burst in among them. Then followed a massacre; no less than three thousand persons are said to have been slain, and their bodies cast into the Tiber. Pnlvius Flaccus and his elder son Marcus hid themselves in the house of a client, but when their pursuers threatened to burn down the whole street unless they were given up, an informer was promptly forthcoming. They were beheaded on the spot without form of trial. Caius Gracchus was not found upon the Aventine. No one had seen him during the fighting: he had shut himself up in the temple of Diana, and proposed to commit suicide when the barricades were forced. But two of his friends, the knights Pomponius and Laetorius, took his dagger from him, and persuaded him to fly before it was yet too late there was still a way of escape by the Porta Trigemina and the Sublician bridge. Before leaving the temple, Caius is said to have fallen upon his knees, and with upraised hands to have prayed to the goddess “that the people of Rome, for their ingratitude and base desertion of their friend, might be slaves for ever.” If the story is true, it well explains the mood of sullen despair which had lain heavy on his soul for the last twenty-four hours. He had pushed things to extremity, and then his party had melted away from him. All his plans, as he now saw, had been futile from the first, because he had mistaken the urban rabble of to-day for the ancient citizens of Rome.

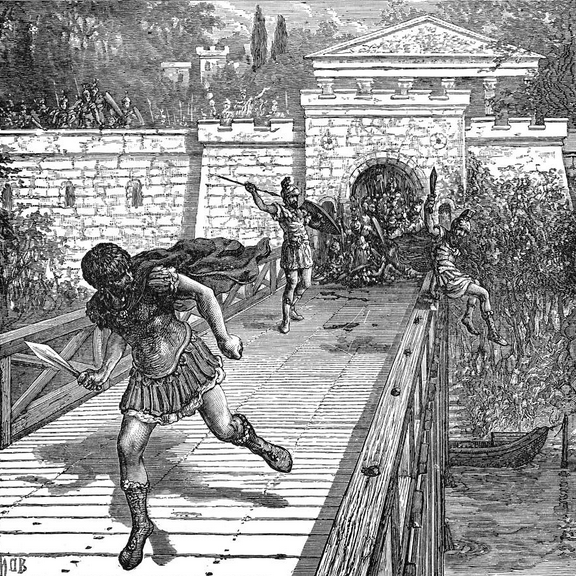

Caius and his two friends were sighted by some of the victorious Optimates as they fled down towards the Tiber. They made what speed they could, but the reformer presently stumbled and fell, spraining his ankle so that he could no longer move with ease. By the river gate the pursuers were nearing them; thereupon Pomponius bravely turned to bay, and held them back for a moment at the cost of his life. Laetorius did as much on the Sublician bridge, and by their sacrifice Caius, now accompanied only by a single slave, reached the suburb under the Janiculum beyond the water. As he hobbled on, supported by his retainer, the streets were full of idle spectators, who shouted to him to run his best, as if he were a competitor in the circus. But no one gave him the least assistance, though he kept calling for a horse as he went. Before the Optimates came up, he had got beyond the last houses, and reached the Grove of Furina, just outside the city. He was seen to enter it, but when the pursuers burst in after him, they found both him and his companion lying dead. At his master’s orders the slave had stabbed him to the heart, and had then turned his weapon against himself. The head of the reformer was cut off and carried to the Consul: his body was cast into the Tiber Opimius carried out his promise, and gave the bearer of the head its weight in gold — seventeen pounds eight ounces, as tradition recorded.

Thus miserably ended the career of the younger Gracchus, a man who, both as a politician and as an individual, was strangely compacted of strength and weakness. Clearly he was no single-minded enthusiast like his brother. He had studied statecraft, and had learnt not to be over-scrupulous in his methods. If, indeed, he was set on regenerating the people of Rome, he chose the strangest allies and employed the most doubtful means. He must have been perfectly well aware of what he was doing, when he purchased the support of the urban rabble by the gift of the corn-dole, and that of the greedy Equites by surrendering to them the unhappy province of Asia. When the means are so obviously immoral, one is driven into doubting the purity of the end which they are intended to subserve. Was Gracchus really set on saving Rome from the economic and constitutional perils which were sapping her strength? Or was he rather an ambitious politician yearning for power at all costs, and eager to revenge on the Senate his brother’s death? It is easy to read his career in either light, yet each reading must be full of contradictions. If we hold, with Mommsen, that Caius was deliberately trying to make himself tyrant of Rome, we can easily understand all the less worthy episodes of his career. The man with such an idea in his head would not have shrunk from using unworthy tools or practising any sort of political charlatanry. To purchase the aid of the rabble or the knights by bribes, to flatter the hopes of the Italians who desired the franchise, would be appropriate moves for one who aimed at repeating the career of Cypselus or Peisistratus. But this theory leaves unexplained the reluctance which Caius manifested at the end to engage in actual civil war, the want of energy which he displayed in organising his party for the final conflict, and the melancholy apathy which he showed during the last twenty-four hours of his life. If he had really aimed at supreme power, such conduct could be explained by physical cowardice alone, and of that not even his enemies dared to accuse him. A would-be tyrant would have armed and organised bravos, have attacked the Senate instead of assuming the defensive, and have thrown himself into the battle with frantic energy. All the doings of Caius, on the other hand, are those of a man forced into violence against his will, and obviously doubting whether death was not preferable to the guilt of stirring up civil war. They are not the acts of one who wishes to grasp at supreme power and cares not how it is attained.

On the other hand, as we have already seen, it is still more impossible to explain his career by representing him as a single-hearted friend of the people, who thought nothing of himself, and only aimed at regenerating the Roman state. Ambition, revenge, the reckless use of unworthy methods, are too easily discernible in many of his actions.

Probably the true way of reconciling the contradictions of the life of Caius is to realise that though he possessed many of the instincts of the tyrant and the demagogue, there was also latent in him much of the ancient Roman civic virtue. He loved to rule, he was unscrupulous in his methods, he hated fiercely the Optimates and all their works; but at the same time he had a genuine wish to serve the state; he showed it by persisting in his schemes for transmarine colonisation and the enfranchisement of the Italians long after they had become unpopular. A mere self-seeker would have dropped them the moment that he was certain that they failed to please the rabble of the Comitia. When at last he found himself borne on irresistibly toward civil war, Caius was deeply grieved. He faced it with reluctance, and finally had it thrust upon him, against his will, by the reckless folly of his subordinates. The responsibility, no doubt, must ultimately rest upon his shoulders: he might have retired to bide his time instead of fighting. But to do so was almost impossible: he was surrounded by excited partisans whom he could not control, and if he had gone back, he would have seemed to be betraying them to his and their enemies. The outburst of actual war and the reformer’s dreadful end were melancholy but inevitable.

______________________________

[1]

![]()

[2]

![]()

(Go back to previous chapter)

(Continue to next chapter)