Editor’s note: The following comprises the ninth, and final, chapter of Seven Roman Statesmen of the Later Republic, by Sir Charles Oman (published 1902).

IX. Caesar

Many and diverse have been the views taken of Caesar and his career during the nineteen hundred and forty-six years that have elapsed since his death. He did much to shape the future destinies of the world, more perhaps than any other single man that has ever lived, and even in the darkest times of the Middle Ages his story was not forgotten. It may be said that when we have ascertained the way in which Caesar was regarded in any particular century, we know at once the general character of that century’s outlook on history. From the days of Charlemagne down to the Renaissance the Holy Roman Empire was the great political ideal of Christendom. Caesar, as the founder of that empire, was regarded as a semi-divine figure; he lacked but Christianity to make him the patron saint of Europe. Certainly the nimbus would have sat upon his head with as good a grace as on that of Constantine, whose tardy baptism hid a multitude of sins and crimes from the eyes of the Middle Ages. But, pagan though he was, Caesar commanded the unquestioning respect of thirty generations of Christians. The best proof, perhaps, of the aspect that he presented to the men of mediaeval Europe is that Dante, in his vision of the midmost hell, where the worst of all sinners suffer the direst of all punishments, saw three figures only in the mouth of the arch-fiend — Judas Iscariot, Brutus, and Cassius. The traitors who murdered their master in the Senate-house found only one fit companion, the traitor who betrayed his Master in the Garden of Gethsemane. Astounding as such a view appears to us, we must recognise that it was entertained by the best minds of the Middle Ages. Dante was no ignorant chronicler, but a much-read man, a great political thinker, who looked out on a broad field of historical knowledge before he drew his conclusions.

Ere three centuries more had gone by, Brutus and Caesar had changed places in popular estimation. The scholars of the Renaissance, with their Plato and their Plutarch before them, had reconstructed the old republican ideas of the elder world. To them Brutus was the “last of the Romans,” the martyr of freedom, and Caesar’s murder was “tyrannicide,” the righteous slaughter of the enemy of the state. Instead of being the revered founder of the sacred empire, the dictator had become the splendid criminal who made an end of laws and liberty. His greatness could not be impeached, but he served as the type of reckless ambition which strides through battle and ruin to a bloody grave. This was the Caesar that Shakespeare knew; it needs but a glance through his tragedy to see that Brutus is the hero. Caesar, in spite of all his genius and his magnanimity, is at bottom the man in love with power, who cannot be happy till he has added the sceptre and the crown to the imperator’s purple robe. There is no hint that he desired to rule for others’ benefit, to reform the world, to reconstitute an empire that was falling into hopeless rottenness.

Yet another four hundred years have gone by, and now a third reading of Caesar’s career is presented to us. We are told to recognise in him the great “saviour of society”; the man who saw that the Republic had gone too far on the way to decay to be capable of restoration, and who resolved to save the citizens in spite of themselves, even if it were necessary in the process to sweep away all the old constitutional landmarks and to introduce autocracy. Mommsen, the most extreme advocate of this school, goes so far as to praise in Caesar the man who felt within his breast “true kingly greatness,” and therefore rightly felt that he must make himself a king. The doctrine seems dangerous. Of a thousand able and pushing young men who fancy themselves the chosen instruments of fate, nine hundred and ninety-nine turn out to be of the type of Alcibiades or Clodius or Rienzi, and only the thousandth is a Caesar. It does not seem wise to encourage the man of ability to regard laws and constitutions as trifles, which he may sweep away in the justifiable endeavour to assert his personality and live his life.

Everyone must grant that the Roman Republic, with its absurd and antiquated state machinery, had gradually sunk into a hopeless slough, from which it seemed impossible that it could ever be dragged out. There was even less hope of salvation from the Democratic party than from the Optimates; both factions, their ideals and their programmes, were hopelessly played out. But in spite of all, we refuse our moral sympathy to the affable, versatile, unscrupulous man of genius who made an end of the old order of things. Caesar had many aspects: as the manager of mobs and the puller of political wires — as the general — as the legislator — as the organiser of provinces, colonies, and municipalities — as the litterateur and the man of fashion, we know him well. But Caesar the altruist is a fiction of the nineteenth century. To read into his many-sided activity the ideals of a benevolent prophet, who wished to restore the Golden Age, is absurd. Rather was he a brilliant opportunist, dealing sanely and practically in turn with each problem that came before him. Enlightened ambition and the love of doing work well, if it has to be done at all, explain his career. Of real unselfishness or idealism there is not a trace; if he ever denied himself anything that he desired, it was because he saw that the result of indulgence would be dangerous to his political schemes. His self-restraint was strong enough to enable him to refuse even the crown itself, the dearest object of all his wishes, when he saw that the move would be unpopular. But it was policy and not conscience that kept him back on this and on many another occasion.

To represent Caesar, even in his later years, as a kind of saint and benefactor who had lived down his earlier foibles, is wholly untrue to the facts of his life. The man is consistent all through his career; the dictator of B.C. 45 was but the debauched young demagogue of B.C. 70 grown older, riper, and more wary. Those who represent him as a staid and divine figure replete with schemes for the benefit of humanity, need to be reminded that at the age of fifty-four, in the year of the victory of Pharsalus, he was ready to lapse into undignified amours with a clever and worthless little Egyptian princess. It is worse still that two years later, aged fifty-six, he could condescend to write and publish his “Anti-Cato.” To pen a satire — and a poor satire at that — on an honest and worthy enemy, whose ashes were hardly yet cold, was worthy of a second-rate society journalist. The monarch of the world was at bottom the same man as the clever young scamp whose epigrams and adulteries had scandalised Rome thirty years back.

To understand Caesar as a whole, we must look not merely at the wonderful military and administrative achievements of the last fifteen years of his life, but at the record of his chequered and turbulent political career from B.C. 70 to B.C. 58, when he was posing as the hereditary chief of the Democratic party, and winning his first start in political importance by his talent for self- advertisement and the management of mobs.

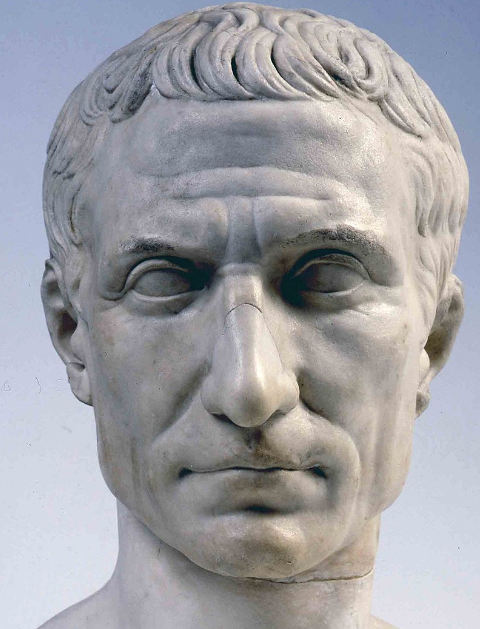

The Julii were among the most ancient — by their own showing they were far the most ancient — of all the old patrician houses. There had been consuls of their name in the first century of the Republic, and when it grew fashionable to construct an elaborate family-tree going back to the days before Romulus, the Julii connected themselves with Aeneas, asserting that lulus was an alias of Ascanius, the eldest son of the Trojan hero. They worshipped as their family patroness Venus Genetrix — a circumstance which may either have been the cause or the result of their claim to descend from Aeneas and his divine mother. Remembering that Virgil’s Aeneid was one of the remote consequences of the construction of this ambitious pedigree, we must be grateful to the domestic mythographer of the Julii. The name Caesar crops up for the first time in the third century before Christ: from B.C. 208 onward there had been a long and not undistinguished succession of consuls and praetors in the house. None of them won a reputation of the first class, but many had been well-known figures in their day: we may especially note Caius Caesar the orator, a contemporary of Sulla, and Lucius Caesar, who gave his name to the famous law which enfranchised the Italians in B.C. 90. The greatest of the house did not descend from either of these men, but came from a younger branch. His father was by no means a notable personage, though he attained the praetorship: of his grandfather nothing is known but his name. The Julii had for the most part adhered to the Optimate faction, as befitted a family of such ancient descent; three of them had perished in the massacres of Cinna, but Caius, the father of the dictator, would seem not to have shared the family views : we find him living quietly under the Democratic rigime of B.C. 87-84, and his sister Julia had been married to no less a person than Marius himself, a fact which may have gone far to determine her brother’s politics.

The connection had, at any rate, a lasting influence on the career of Caesar himself. His fierce old uncle-by-marriage took an interest in the lad, and caused him to be made flamen dialis in the year of the great massacre, although (having been born in B.C. 102) he was at that time only fifteen years of age. The flamen’s cap came to him from the brows of the virtuous Cornelius Merula, one of the countless victims of Marius’s reign of terror.[1] It should surely have brought ill-luck to the boy; but Caesar, till he came to the fatal Ides of March, was the child of fortune. He escaped in the evil day when Sulla came back from Greece in B.C. 83 to avenge the murdered Optimates. His youth saved him : he was but nineteen, and though he was the nephew of Marius and had married the daughter of Cinna, Sulla let him live. This was all the more astounding because the lad had refused to divorce his wife, a course which had been dictated to him as necessary to propitiate the conqueror. Indeed, Caesar had to go into hiding for some time, till influential relatives begged him off. But we may probably dismiss as a fiction the tale that Sulla, while he spared him, muttered to his friends that “in this loose boy there were the makings of many Marii.” The story bears on its face every mark of having been forged long after, when Caesar had already grown to greatness. If Sulla had really supposed that the lad was dangerous, he was far too conscientious a party man to have spared him. All that Caesar suffered at the hands of the Reaction was the loss of his priesthood, and that of his wife’s large fortune; for the property of Cinna, like that of the other Democratic leaders, was forfeited to the treasury.

We know little of Caesar’s life for the next few years. He was still very young, and politics in the earlier days of the Sullan regime were dangerous. Indeed, he would seem to have left Rome in order to keep out of the dictator’s notice. We find him serving in B.C. 80-79 under Minucius Thermus at the siege of Mytilene, where he gained distinction by saving the life of one of his comrades, and was rewarded by a civic crown. If Suetonius, ever greedy after scandals, is to be believed, he also won attention in Asia, in another and a less creditable way, by his licentious private life. When Sulla died, Caesar returned to Rome; but it is noteworthy that he is not said to have taken any part in the agitation set on foot after the dictator’s death by the heady and incapable Lepidus. The rising was fatal to all of the surviving Democrats who were rash enough to entrust their fate to such an imbecile leader; but Caesar was not found among them.

We hear of him as taking his first steps in political life in the year after the fall of Lepidus, when he prosecuted the pro-consul Gnaeus Dolabella — one of the old Sullan gang — for maladministration in Macedonia. But the senatorial judges acquitted him, as they also did C. Antonius Hybrida, another and a more disreputable member of the same ring, when Caesar impeached him in the following year. This notorious ruffian was destined to survive, and to take a prominent part thirteen years later, first as the associate and then as the betrayer of Catiline. It was a good advertisement for a young man of decidedly Democratic antecedents to be able to accuse such persons, even if he could not get them convicted. In B.C. 77-76 the Optimates were still so much in the ascendant that it was something even to dare to attack them.

After the trial of Antonius, his young accuser went off again to the East. It is said that he had not been satisfied with his own speeches, and that he was determined, before resuming his political career, to learn all the tricks of the orator’s trade. With this object he sailed for Rhodes, where he intended to study under the celebrated rhetorician Apollonius Molon, who had also been one of the instructors of Cicero. But these years were the golden age of piracy in the Levant, and as Caesar sailed by the island of Pharmacusa, off the Ionian coast, his galley was captured by a Cilician corsair. The whole tale of his captivity, as told by Plutarch and Suetonius, is too full of characteristic traits of the young man to be omitted. The pirates, who were business-like persons, bent on ransom and not on massacre, took stock of their prisoner, and rated him at twenty talents — about £ 5000 of our money. Caesar professed to be deeply hurt at being valued at such a small sum, and said that he was well worth fifty talents. This was a kind of captive to whom the Cilicians were unaccustomed; they eagerly accepted him at his own valuation, and let his companions and freedmen depart to Miletus to raise the money. Caesar remained alone at their headquarters, accompanied only by his physician and two valets. “He lived among the pirates for thirty-eight days,” says Plutarch, “treating them as if they had been his body guard instead of his gaolers. He used to send out, whenever he wished to take his siesta, and order them to keep quiet. Fearless and secure, he joined in their diversions, and took his exercise among them. He wrote poems and orations, and rehearsed them to the gang, and when they expressed too little admiration, he called them blockheads and barbarians.” He would often tell them, in a jesting manner, that when he should be liberated, he intended to come back and crucify them all, a threat which they took as a piece of playful humour on the part of this affable young gentleman. But he was speaking in perfect candour. The moment that the fifty talents of ransom money had been paid, he hired a few galleys at Miletus and ran out to look for his late captors. He found them still at Pharmacusa, celebrating their stroke of luck by a great carouse. He surprised them, captured the whole gang, and recovered his money intact. He then took them to Pergamus, to hand them over for execution to Junius, the governor of Asia. But learning that the worthy magistrate had an itching palm, and would probably let off the Cilicians for a bribe, he proceeded to put them to death on his own responsibility. He crucified the whole of the late audience of his poems and orations, after having first, as a special favour, cut their throats before he affixed them to the cross.

Caesar then resumed his interrupted voyage to Rhodes, and studied rhetoric with Apollonius for some months. His stay in the island was brought to an end by the news that one of the generals of Mithradates had invaded proconsular Asia. He sailed to the mainland, raised some levies at his own expense, and soon expelled from the province the raiding cavalry of the Pontic king (B.C. 74). At this moment he received letters from Italy informing him that he had been elected a pontifex, in the place of his deceased uncle, C. Aurelius Cotta. He returned at once to Rome to take up this not unimportant religious office; how such a comparatively unknown young man came to be elected to it, and that too in his absence, our authorities do not tell us.

From his return to Rome (B.C. 73) down to the time of his praetorship in B.C. 62, Caesar was gradually working himself up from a position of comparative insignificance to that of the managing director of the Democratic party. How popularity with the urban multitude was achieved in the last days of the Roman Republic we know only too well. The days were long past when the favour of the citizens could be won by fluent oratory and noble sentiments alone. The would-be demagogue had not only to tickle the ear of the sovereign people with his harangues; he had to be continually slipping bribes into its eager palm, and filling its insatiable belly with doles and distributions of corn. The age of Tiberius Gracchus was long past; Saturninus and Sulpicius were the heroes and martyrs whom the Democratic party regretted. Clodius was looming in the not far distant future.

Dazzled by the magnificent career of Caesar in his middle age, many writers have striven to represent him as an enlightened statesman and a true lover of Rome (even of the world at large!) in his youth. It is difficult to support any such theory from the facts of his early years of political activity. It must be confessed that he appears as a demagogue of the usual type. If he had died in B.C. 62, he would be dimly remembered in history as a second Glaucia, whose wit was less vulgar than that of his model, as the legitimate successor of Sulpicius and the natural predecessor of Clodius. He fought with the common weapons and with the usual methods of other popular leaders of his day. We perpetually hear of him as organising and leading down to the Forum or the Campus Martius gangs of armed rabble. He broke up assemblies, or overawed them with the stones and bludgeons of his satellites. He swept the streets, and fought on equal terms with the hired bands of the Optimates. He was the ally and assistant of Gabinius and Manilius in all their turbulent proceedings in 67 and B.C. 66; it was his gangs which supported the stupid Metellus Nepos in B.C. 62, and bruised and battered the bellicose Cato. Worst of all, he was more than suspected of having been deeply engaged in the Catilinarian conspiracy, at least in its earlier stages. Not one, but many authors tell us that in the plot of B.C. 66 Caesar and Catiline had joined their bands for the coup d’etat which was to make Crassus Dictator and Caesar his Master of the Horse. Why the outbreak never took place is explained to us in half-a-dozen different versions, one of which says that it was Caesar, not Catiline, who failed at the critical moment to give the signal for the rioting to commence. Whatever may have been the exact truth at the bottom of the many floating rumours which have survived, it is certain that, rightly or wrongly, Caesar was regarded as having been even more deeply implicated than Crassus in the obscure plots of B.C. 66-63. We may guess that he ceased to be an active mover in them only when he discovered the full scope of Catiline’s designs, and realised that he was too reckless and violent to make a safe coadjutor. Those modern writers who urge that it is improbable that the two men could ever have acted in concert, use as their main arguments two very weak pleas. The first is that Caesar was too magnanimous and patriotic to have joined in a conspiracy which involved treason and massacre. The second is that Catiline was such a notorious criminal and ruffian, that no sensible man, with a career before him, would have compromised himself by taking such a partner. But the first argument is wanting in historical perspective. Caesar, the demagogue of B.C. 66, was a very different person from Caesar the dictator of B.C. 48. We must not argue back from his last stage to his first; an ambitious young man, with his way to make in the world, may well have contemplated things which would not have commended themselves to the statesman who, twenty years later, had fought his way to supreme power. The second argument — that Catiline was frankly impossible as a colleague — falls to the ground before the fact that the respectable Cicero was in B.C. 64 only too eager to secure him as a friend and ally. What Cicero desired may well have commended itself to the more adventurous Caesar. Evidence as to good or bad character is as useless in the one case as in the other. Caesar, as a popular demagogue, must have rubbed elbows with so many strange people between B.C. 73 and 60, that we shall not easily believe that he drew the line above Catiline’s name.

Indeed, it would be useless to pretend that Caesar paid any particular attention during his early years to the reputation of his associates, or indeed to his own. His way of life did not resemble that of the blameless Tiberius Gracchus or the priggish Livius Drusus. He had rather borrowed his manners and morals from Sulla. He was anything rather than an austere fanatic or a model of all the virtues. Romans of the old school detested him for his absurd fastidiousness in dress; the long fringes of his toga, the breadth of his purple stripe, and the peculiar loose style in which he girt himself displeased them. They sneered at his exquisite care over his toilet; his barber not only shaved him, but finished him off with tongs and tweezers. When an early baldness came upon him, every art of the hairdresser was employed to hide the growing deformity. Cicero once observed that it had been long before he had taken seriously, or dreaded as an enemy of the state, the man who could spend so much time and thought over his personal appearance. In his latter days, it was remarked, nothing pleased him so much, of all the honours which were heaped upon him, as the grant of the laurel crown, which served to hide the disappearance of his once abundant locks. But Caesar was much more than an exquisite. It is doubtful whether his recklessness in money affairs or his promiscuous amours were the more displeasing to those of his contemporaries who still loved the old Roman virtues. Of all the rakes of Rome, he was by far the most notorious. His admirers who plead that “his life was perhaps lax according to our notions, but within the bounds set up by the age in which he lived,” are grossly understating his reputation. He was, so to speak, the inevitable co-respondent in every fashionable divorce; no household was sacred to him ; the elder Curio called him in one of his orations, “omnium mulierum virum.” When we look at the list of the ladies whose names are linked with his in the pages of Suetonius, we can only wonder at the state of society in Rome which permitted him to survive unscathed to middle age. The marvel is that he did not end in some dark corner, with a dagger between his ribs, long before he attained the age of thirty. The Romans did not fight duels, but they understood the use of the assassin for the righting of domestic scandals. It is strange that none of the injured husbands named by our historians took advantage of the fact that bravos were to be hired on moderate terms in every court of the Suburra. But Caesar lived on, and his reputation seems to have been a source of peculiar pride to his satellites. When he entered Rome in triumph, his veterans sang behind him a lewd song with the burden —

“Urbani, servate uxores! Calvum moechum adducimus!”[2]

These were certainly odd beginnings for a saviour of society. Unfortunately the end was even as the commencement; there were scandals in Gaul, and even Cleopatra had a successor in the last years of the old dictator’s life — Eunoe, the wife of Bogud the Moor. It is grotesque to have to remember that in spite of his own career he was the author of the famous dictum that “Caesar’s wife must be above suspicion.”

If there was any other point of Caesar’s character even more strongly marked than his licentiousness, it was his power of getting through money — especially other people’s money. There was only one thing in which he was economical, his eating and drinking, for he was free from the very common Roman vice of gluttony.[3] But on everything else his expenditure was reckless. He did not, like Crassus, merely spend money on politics with the definite aim of getting on in the world. Much of his waste was on mere personal luxury; furniture, plate, gems, jewellery, pictures, slaves of distinguished appearance or accomplishments, he never could resist. He once (but this was in his later days) gave a lady friend a pearl which he had bought for 6,000,000 sesterces — .£60,000 of our money. As an example of his recklessness, we are told that long before he had got to the front in politics, and while he was still overwhelmed with debts, he built himself a villa at Aricia at great cost. When it was finished, he found that there was something about its architecture that he did not like, and had it pulled down to the very foundation stone.

But it was, after all, on politics that Caesar threw away the greater part of his money. He had worked through all his private fortune before he had reached the age of twenty-four. When he entered on his quaestorship he was already 1300 talents in debt, and it was not till more than ten years after that he was in a position to begin to pay off what he owed. By that time he had exhausted other lenders, and was depending on the inexhaustible purse of Crassus alone. The millionaire had picked him out from among all the other young demagogues of Rome, and had been so much struck with his ready ability and boundless self-confidence, that he was prepared, in return for political services, to finance him to any extent. The greater part of the money which Caesar ran through was lavished on the most useless and extravagant bribes to the multitude. He was determined to surpass all who had ever lived before him in self-advertisement. When he held the aedileship, three hundred and twenty pairs of gladiators died for the amusement of the mob. He spent countless sums in theatrical exhibitions, processions, and entertainments of the public at free dinners, which cast into the shade even Crassus’s great open-air banquets of B.C. 70. The more useless and extrayagant was his outlay, the better the urban multitude was pleased. After this, one begins to understand the freaks of Caligula and other descendants of the Caesarian family. But the wild extravagance caught the popular eye, and was much more admired than the magnificent porticos which he built to the Capitol, or the great Basilica Julia which he erected for the improvement of the sittings of the law courts.

The art of self-advertisement, in short, Caesar possessed to the highest degree. Even when he had the misfortune to lose near relatives, their funerals served him as a means for providing the people with a splendid show. When his aged aunt Julia, the widow of Marius, died, he took the opportunity of startling the assembled multitude by parading before them the long forbidden effigy of the old lady’s deceased husband, to the joy of all Democrats. A fragment of Caesar’s funeral oration over Julia has been preserved by Suetonius; it is very characteristic, as showing that the affectionate nephew knew how to speak one word for his respected aunt and two for himself. “On the mother’s side,” he said, “Julia descended from the ancient kings, on the father’s from the immortal gods themselves. For her mother and my grandmother, Marcia, descended from Ancus Marcius, the fourth king of Rome; while we of the Julian house trace back our origin to Venus herself. In our family, therefore, we combine the divine right of kings, who are the greatest among men, and the worship of the gods, to whose power even kings must bow.” What could be more flattering to the sovereign people than to see a gentleman of such illustrious descent courting their approval? The mob, it is said, “loves a lord.” How much more must it love a suitor who was, as he carefully pointed out to them, not merely of noble, but of divine descent! Another funeral oration of this same sort was made by Caesar over his second wife, Cornelia. In earlier days, we are told, only ancient matrons were honoured with a public funeral and a laudation from the rostra. He first broke through the custom, by celebrating the show for a spouse who had not yet passed her prime. “This contributed,” says Plutarch, “to fix him in the affections of the people, who sympathised with him, and considered him as a man of feeling, and one who had his social duties at heart.” They must have been disappointed when he divorced instead of burying his third wife, Pompeia, after the scandal concerning the mysteries of the Bona Dea.

Caesar, then, was, from his earliest entrance into politics, working for the definite end of achieving greatness, but what sort of greatness he can hardly himself have realised. Certainly we may be excused from holding, with Mommsen, that he had recognised within his breast the promptings of a kingly heart, and was determined to be a king. That development belongs to a much later date. Yet there can be no doubt that his aim was always to get to the front. Everyone knows how he wept when he looked upon the statue of Alexander the Great, and muttered that the Macedonian had conquered the whole East before reaching the age at which he himself had merely obtained the quaestorship. It was a few years later that passing, on his journey to Spain, through a miserable village in the Alps, he exclaimed to his travelling companions that he would rather be the first man there than the second man in Rome.

But it seems clear that Caesar in his early days was set on reaching political greatness rather by the dusty and dirty path through the Forum, than by the road through the battlefield, by which he was ultimately destined to come to the front. He was determined to be the first man in Rome, but till he discovered, late in life, that he chanced to be a military genius, he intended to rise by the aid of the reeking multitude of the Suburra. The Democratic party had hitherto been led by a dynasty of failures; he would provide it with a chief who had none of the weak points of his predecessors: he would be a Gracchus who should be neither austere nor impracticable; a Drusus destitute of priggishness; a Glaucia whose jokes should always be in good taste; a Saturninus whose riots should always be interesting, so as not to end in boring the public opinion of the streets by mere commonplace repetitions of club-law and arson. All this he became: yet he felt, when he had achieved this particular form of greatness, that there was still some thing wanting. It was unsatisfactory to remember that all his largesses had to come out of the pocket of Crassus, and that he might at any moment be given some dirty job by the stolid millionaire and be unable to refuse it. Still more tiresome must it have been to realise, as Caesar did realise without a doubt, that an end might be put to all his games on the day when Pompey should be provoked to throw his sword into the balance. None knew better the powerlessness of a mob against an army; one of the most striking recollections of his boyhood must have been that of the bloody day when Sulla’s legions cleared the gangs of Sulpicius Rufus out of the streets, and came, first of all Roman soldiers, armed and triumphant to the Forum and the Capitol. There must have been a moment, its date we cannot dare to fix, when Caesar finally came to the conclusion that the domination which he had achieved in the streets would avail him nothing if ever swords were drawn. When once he had realised the fact, his mind must have been turned to the only possible alternative. Had he within himself the makings of a great general? That he had a soldier’s courage and readiness he had proved at Mytilene in B.C. 79, and in Asia in B.C. 74. That he could assert a personal ascendency over his followers he knew well, from his experiences during ten years of mob-management. But a man may be a good fighter and an inspiring leader, and yet lack the main qualities of generalship. Caesar, like other young Romans of his class, had undoubtedly studied the theory of the art of war from the popular Greek manuals then in vogue. But so had many an incapable Optimate who had disgraced himself on the battlefield: it yet remained to be seen whether he possessed real military ability. This could only be learnt by making the experiment. The first occasion on which Caesar had the opportunity of trying his hand at the game of war upon a considerable scale was when he went to Spain as propraetor in B.C. 61. This governorship was the turning-point in his whole career: his contemporaries supposed that it was important to him merely because it gave him the chance of paying off the enormous debts which hung round his neck like a mill-stone, and had made him the tool of Crassus. This no doubt had some weight in Caesar’s eyes: it is certain that by some wonderful tour de force he wrung vast sums out of Spain without earning a specially bad name for rapacity. But a Roman governor of those days had to emulate the exploits of Verres and Antonius if he wished to shock the public opinion of his contemporaries. There can be no doubt that Caesar must have shorn the Spaniards close, to raise the money that paid off his debts; but, probably (as the Irish wit wrote of Lord Carteret), “he had a more genteel manner of binding their chains than most of his predecessors.” A considerable part of the sum, too, was secured by the selling as slaves of his numerous prisoners of war, an obvious method of money-making on which the successful commander could always rely.

But the financial importance of Caesar’s Spanish governorship was nothing in comparison with its military importance. For the first time he found himself at the head of a considerable army — he took over two legions and raised a third — and able to deal with it as he pleased. Nor were enemies wanting; never, since the Spanish provinces had been formed, had border warfare ceased on their north-western frontiers. The Galaeci and Cantabrians still maintained their freedom in their hills, and many of the northern Lusitanians were practically independent, though nominally included within the borders of the empire. Even if Caesar had not been wishing to try his fortune as a soldier, he would have been compelled to chastise these fierce hillmen for their perpetual raids into the more settled districts. But he was only too eager to discover his own possibilities in the military sphere. He carried out a long and difficult campaign in the valleys of the Lower Douro, the Mondego, and the Minho with complete success, showing an untiring watchfulness and a wary skill that must have surprised his soldiery, who knew him only as the hero of the Roman streets. It must have been in this Galician and Lusitanian campaign of B.C. 61 that Caesar came to know himself, and to recognise that he was capable of the highest things in the field. It must have been a stirring moment, for it changed the whole of the outlook of his life. He need no longer make it his loftiest aim to be the king of the Suburra and the hero and model of the young rakes of Rome. He might now aspire to beat Pompey on his own lines. If he could obtain a great military province and raise a large army, he might hope to achieve a more splendid reputation than that of the conqueror of the Pirates and of Mithradates. There would be no need to shed futile tears again before the statue of Alexander the Great; he might, after all, make up for the years lost in demagogy and in evil living. At forty-one years of age it is still not too late to start on the soldier’s trade, though there is hardly another case in history, save Oliver Cromwell, of a general who discovered his avocation when so far advanced in middle life. Endowed with a splendid physique, which had not been ruined even by the twenty ill-spent years of his Roman career, Caesar was still wiry, alert, and untiring. Probably the one virtue of his youth, his contempt for the delights of the cup and the platter, now stood him in good stead. He could march and starve with the sturdiest of his own legionaries. There seemed to be no danger that his body would fail him, and his mind was at its best. The readiness and ingenuity which he had always displayed in the tactics of the Forum were easily transferred to the tactics of the field. The power of inspiring confidence, which had enabled him to discipline even the demoralised city mob, served him still better with the simple soldiery. Indeed it must have been a comparatively easy task to manage the conscripts of the Spanish or the Cisalpine province after managing the unruly and untrustworthy denizens of the Roman slums.

We cannot doubt that Caesar returned to Rome in B.C. 60 with one desire before his eyes, that of obtaining first the consulate, and then, as proconsul, a military province of the first class — the Gauls for choice, since, there he would both remain comparatively near to Italy, and also have a splendid field for operations and a great recruiting ground. It was fortunate for him that the change in his outlook on life, which had resulted from his Spanish campaign, was not apparent to his contemporaries. To Pompey and Crassus, no less than to Cicero and Cato, he was still the rakish demagogue of the past twenty years. Had Crassus guessed that his late debtor, the manager for many a day of his hirelings, was aspiring to climb to greatness over the pile of his money-bags — had Pompey known that the man who offered to deliver him from the insults of the Senate, was intending to supersede him in the position of Rome’s greatest general, there would have been no First Triumvirate. But the change in Caesar’s character and designs was hidden from them: they allied themselves, as they supposed, with a mob-manager of genius, who undertook to clear the streets for them and to work the machinery of the Comitia. There was little in Caesar’s conduct in B.C. 60-59 to make them suspect that they were giving themselves a master, when they acquiesced in the bargain. He was to secure them what they desired, and they, in return, were to concede to him the consulship and the Gallic Provinces.

The combination of Caesar’s management and Crassus’s money carried all before it, and the consulate was duly secured to the Democratic candidate. In older days it would have been a serious drawback that he failed to carry the election of L. Lucceius, the obscure person who ran with him, and that he was saddled with Bibulus, the most obstinate of Optimates, as his colleague. But in Caesar’s year of office it did not matter much whether he had a colleague or not. His consulship was a sort of carnival of illegality and mob law, which made a fitting close to the whole of his demagogic career. He violated every rule of the constitution with a cheerful nonchalance that surprised even his own lieutenants. He openly displayed armed men in the Comitia; he not only drove away the partisans of the Senatorial party by force — that was now the ordinary rule in domestic politics — but arrested and hurried off in custody every one who dared to speak against his proposals — even the respectable Cato himself. His crowning act of illegality took place at the passing of his Agrarian Law; when Bibulus put up three tribunes to veto it, Caesar quietly disregarded them, and proceeded with his business. The Optimate consul sprang to his feet, and began declaiming to the people that the whole proceedings were null and void, and that his colleague was violating the most fundamental laws of the constitution. Caesar had him seized by his lictors, bundled him off the rostra, and told the attendants to see that no harm happened to him, and to turn him loose in some quiet street. Cato and the three dissentient tribunes were treated in the same unceremonious fashion. Then Caesar bade the proceedings go on, and passed his law! If ever majestas, the open and deliberate commission of high treason, took place at Rome, this was the occasion. A magistrate had disregarded the veto of his own colleague and of three tribunes, and had finally laid violent hands on their sacrosanct persons and expelled them from the Assembly. The Optimates wondered that the sky did not fall then and there. But nothing happened, and Caesar declared his bill to be law, and carried out its provisions. Bibulus formally summoned the Senate next day, narrated the indignities that he had suffered, and called upon the Fathers to support him in open resistance, and to declare all his colleague’s doings invalid. He was met with a mournful silence: the days of Nasica and Opimius were over; no one offered to arm his clients and go forth to save the state. The veterans of Pompey and the mob of Caesar seemed too formidable.

So Bibulus shut himself up in his house, and contented himself with posting a daily placard, to the effect that he was “observing the heavens,” and that it was therefore impossible that any legal meeting of the Comitia could take place. By the letter of the law he was undoubtedly right, and every bill that passed during the remainder of the year B.C. 59 was null and void. But what was to be done if the bills were not only carried but obeyed? The wits of Rome called the time “the consulship of Julius and of Caesar,” in derision of the unfortunate Bibulus. It would have been more correct to call it not a consulship at all, but a fine specimen of a tyranny.

Caesar meanwhile went on in his reckless career, passing bills good, bad, and indifferent. Some of them were excellent administrative measures; others — such as the ratification of Pompey’s Asiatic acta — were eminently proper and justifiable. Others again were shameless bribes to the mob or the Equites. The one which struck contemporary opinion as the most objectionable was that which made a plebeian of Publius Clodius. That detestable young man had given Caesar good cause of offence by the scandal at the mysteries of the Bona Dea, and had forced him (not without reason) to divorce his wife. But the consul bore him no grudge; indeed he seems to have regarded him with a sort of parental affection, as the destined successor who was about to repeat his own early career of political riot and private debauchery. Clodius wished to become a plebeian, in order to qualify for the tribunate. Caesar indulged him, and proposed himself the lex curiata by which the adoption of the young man into a plebeian family was managed. The ceremony was carried out in an irregular, not to say a farcical, fashion. No sanction was procured from the Pontifices, the legal notice of three nundinae before the meeting of the Curies was not given. The adopter who undertook to make Clodius his son was a lad of nineteen, one P. Fonteius, who was far younger than Clodius, and unmarried. Yet he was made to profess his want of issue, and the necessity of his adopting a son to continue his race! (As a matter of fact he married not long after, and had many children.) Caesar carried through the scandalous show, and left Clodius behind him as his agent for the due maintenance of mob law and anarchy during his absence in Gaul.

Early in B.C. 58, the moment that his turbulent consulship was over, Caesar hurried off to take over charge of the Gallic provinces and their legions. He had secured himself no mere annual governorship, but a long term of five years of command. Such had been the purport of the Vatinian Law, which was drafted on the same lines as the Gabinian and Manilian Laws that had been passed for Pompey’s benefit nearly ten years before. Clearly Caesar thought that five years would be required to enable him to make his name and to frame his army. What he was to do when his term ran out, we may doubt whether he had yet determined. His Spanish command had been a great experiment — his Gaulish one would be an even greater. As yet he cannot have framed any other intention than that of being the greatest man in Rome. Of what sort his predominance was to be, he had probably formed no fixed plan. All would depend on how affairs went in the land of the Celts.

That Caesar went to Gaul with a fixed intention of carrying the boundaries of the empire to the Rhine and the Ocean there is no reason to doubt. The existing frontier of the Transalpine province was drawn in an illogical and haphazard fashion; beyond it lay tribes in various ill-defined relations of vassalship and amity to Rome. Ever since the Cimbric campaign of Marius, the province had been needing, and always failing to obtain, the hand of a master. But even if Caesar had arrived with the most pacific intentions, he would have been forced to fight before his governorship was six months old. There were troubles brewing on the eastern frontier of Gaul which were already becoming dangerous, not only to the independent tribes, but to the Transalpine dominions of Rome. The Suevian king Ariovistus with a miscellaneous horde of migratory Germans, compacted from many races, had crossed the Rhine, as the Cimbri had crossed it fifty years before, and was threatening to overrun all Central Gaul. At the same moment the warlike Helvetii were deserting their narrow and mountainous home in Switzerland, with the object of conquering for themselves a more spacious and fertile abode in the valley of the Rhone. No proconsul, however slack and indolent, could have avoided interference in both these movements; to Caesar they were an absolute godsend, as they provided him with the best possible reasons for enlarging his army and engaging in active hostilities the very moment that he reached his province.

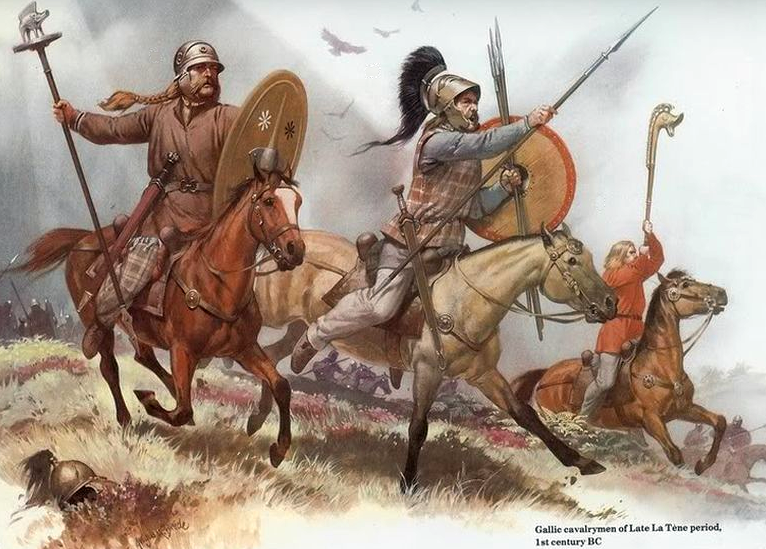

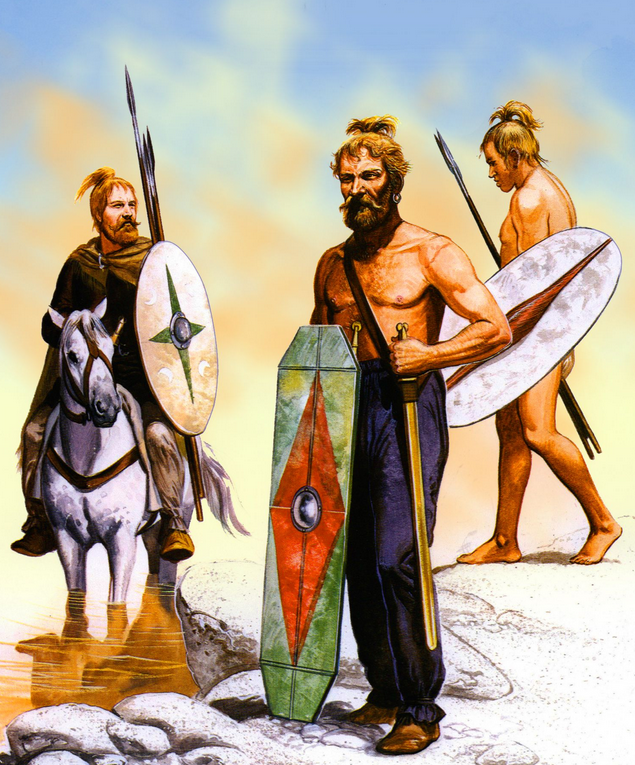

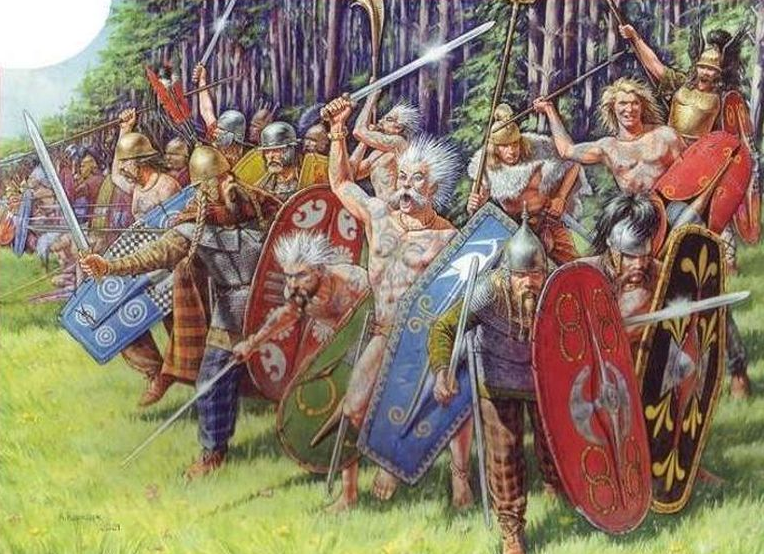

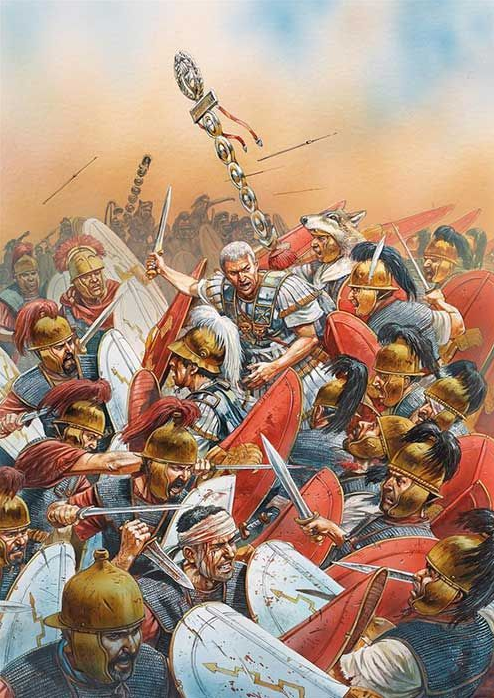

The Gaul and German were enemies well known to the Roman soldier. In marching against them Caesar had none of the disadvantages which Crassus had suffered when he went forth to meet the unknown tactics of the Parthians. The Gaul, indeed, was one of the most familiar foes of the state; the bands whom Caesar fought in B.C. 58-51 were precisely similar to those with whom Camillus or Marcellus had contended two or three centuries before. Their gallant but unstable hordes, “more than men at the first onslaught, less than women after a severe repulse,” were precisely the sort of troops against whom the steady and untiring legion was most effective. The only really dangerous part of their hosts was the cavalry, formed of the chiefs and their sworn henchmen, who were far superior to any mounted troops of whom Caesar could dispose when first he went to Gaul. To withstand them he had to enlist “friendlies” of their own nationality, and Spanish mercenaries: a little later Germans also, for the latter were found to be superior to the Gauls themselves in the cavalry arm. As to the tribal levies of infantry, they were difficult to check at their first rush, but when it was spent the individual swordsman with his immense claymore and big shield was not fit to cope, either in a single-handed fencing match or in a large body, with the well-trained legionary. The rank and file understood this as well as Caesar himself, and their knowledge of the fact was no mean help to their general.

With the Germans it was at first otherwise. The Roman army remembered Arausio quite as well as it remembered Vercellae, and had an exaggerated respect for the “giants” of the northern forests, and their indomitable pluck. At his first encounter with Ariovistus, Caesar had many anxious moments. There was a doubt whether the legions could be trusted to do their best: their general acknowledges that when he marched against the German many of his officers showed signs of malingering, and the rank and file began to make their wills — as if they were going forward to certain death. It required a wonderful mixture of tact and firmness on the part of Caesar to induce his troops to make their first attack on Ariovistus. But when the feat was accomplished the legionary discovered that the Teuton was, if bigger and fiercer, yet even more undisciplined and clumsy than the Celt, and far worse armed. The German tribes, even a century later, had hardly got to the stage of wearing armour or forming an orderly battle array.

Yet both Gaul and German were enemies not to be despised, and it was no ordinary general who could have set out with a light heart for the deliberate purpose of attacking them in order to win a great military reputation at their expense. Nothing but an ever-pressing, unconquerable ambition could have driven Caesar to the taking up of such a formidable task.

To give a detailed account of the eight marvellous campaigns, which laid Gaul at the feet of the great proconsul, does not fall within the scope of our task. We are concerned with the character of Caesar as man and as general, rather than with the annals of his battles and sieges. In the main we must draw our conception of his work in Gaul from his own Commentaries; what information we get from other sources is comparatively unimportant. The book was published with a political object — probably it was written in haste during the year B.C. 50 as a vindication and advertisement of the author’s doings before the eyes of the Roman public. Yet it compares favourably with most works issued with such a purpose: it is reticent and business-like; there is little self-laudation; the greatness of the author’s achievements is not dinned into the reader’s ears, but allowed to speak for itself. Moreover, it is difficult to detect in the Commentaries any very serious tampering with facts. They give, of course, Caesar’s own view of his wars, but they seem as little marred by a desire to hide reverses or to exaggerate successes as those of any other commander who has ever written the narrative of his own campaigns. The general result of the war speaks for itself. It is sufficient to look at the Roman boundary in B.C. 58 and to compare it with that of B.C. 50, in order to see that the main result of Caesar’s activity was much what he claimed. If minor checks are sometimes glazed over, the final triumph was indubitably complete. It can have been no ordinary conqueror who not merely subdued Gaul, but left it behind him so thoroughly tamed that, during the subsequent Civil War, the once turbulent tribes made no serious attempt to rise, and to rid themselves of the wholly inadequate garrison which had been left to hold them down.

There were many things which combined to make the conquest of Gaul a less formidable undertaking than it appeared at the first glance. If numerous and warlike, the Celtic tribes were fickle and faction-ridden. A real national sentiment existed, but there were other sentiments which were stronger. Wherever Caesar went, he found communities which were ready to join him in suppressing their neighbours, either because of ancestral feuds, or because of the self-interest of the moment. Gaul, in the first century before Christ, was much like the Highlands of Scotland in the seventeenth or eighteenth century after Christ. It sufficed that one clan should espouse one rival cause, and its neighbour out of ancient jealousy would take up the other. A power intervening from outside would be certain of support from all the enemies of the dominant tribe or chief of the moment. It has been truly said that Caesar subdued Gaul by the arms of Gauls, just as Clive or Wellesley subdued India by the arms of Indians. In each case the conqueror had a strong nucleus of national troops in his host, but they would not have sufficed for his task if they had not been supported by thousands of local auxiliaries. Moreover, in each case powerful native states backed the invader. The Aedui and the Remi stood to Caesar in Gaul much as the Nawabs of Oude and the Carnatic stood to the British in India. Nor was it merely inter-tribal feuds that made the foreigner’s work easy. The factions within the several communities were almost as fiercely opposed, and as disloyal to the common weal, as the states in general were disloyal to the national cause of Gaul. A great proportion of the clans were torn to pieces by feuds between some predominant chief who aimed at regal power, and the rest of the local oligarchy. If the would-be tyrant was a nationalist, the lesser chiefs called in Caesar to help them — if the oligarchs were nationalists, it was their ambitious rival who made the appeal.

Hence came the futility of the resistance of the Gauls to the great proconsul. They were always betraying each other, the individual sacrificing the tribe, the tribe the nation. So much we gather from Caesar’s own works: to the numerous instances which he gives there must have been many more to be added, of which we have no knowledge. Every one of Caesar’s victories, military or diplomatic, was probably aided by local feuds and jealousies, which an intelligent Gallic witness could easily have explained, but which are omitted in the pages of the Commentaries, whose author could only give the situation as it appeared to himself, not as it appeared to his foes. This is the reason why Vercingetorix, a man of real genius, failed to hold together the patriotic confederacy which he had taken such pains to build up. An appeal to Gallic national feeling might rouse the tribes for a moment, but after a few months particularism resumed its sway. Each one of the confederates suspected the rest of doing less than their share, and then, in sulky resentment, resolved not to be exploited for the benefit of the neighbouring states.

It is certain, moreover, that the Gauls, even when they came together in the largest force, cannot have put in line the enormous armies of which the Commentaries speak. It is always hard to calculate with accuracy the numbers of a tribal levée-en-masse. No doubt Caesar often doubled or trebled the real figures of the hosts that were opposed to him. The ancients had an even smaller power of estimating or realising large numbers than the men of the present age. If we note the tendency among generals of today to swell the figures of savage hordes with whom they have had to deal, we need not doubt that Caesar was liable to the same failing. Every commander in such wars states his own resources at a minimum, and sees those of the foe through a magnifying glass. No doubt the 200,000 swords of the Belgic army at the battle on the Aisne in B.C. 57, and the 250,000 men whom Vercassivelaunus is said to have led to the relief of Alesia are wild and reckless estimates. Yet probably they represent the numbers which the Gauls believed that they had raised, and which the Romans believed that they had faced. There is no reason to think that Caesar invented them, or added extra thousands to the figures which were reported to him. The hordes were enormous; there was no certain method of counting them. The conqueror cannot be much blamed for reproducing the current estimate. Nor can we expect him to point out another fact which was certainly a great advantage to him. Of the wild masses which formed the Gallic tribal levies, only a certain proportion were really formidable fighting men. The horse was excellent: the chiefs and their bands of sworn henchmen and “debtors” were gallant and desperate foes. But the main body of a levée-en-masse must have consisted of half-armed husbandmen, like the English fyrd at Hastings. When the pugnacious and well-armed nobility and their retainers had been killed off in the forefront of the battle, there must have been little power to resist among the ill-equipped horde which formed the bulk of the tribal host.

All this we state to explain Caesar’s triumphs, not to diminish them. If these antecedent advantages had not existed, his task would have been impossible, considering the very modest resources that were at his disposition. Even when all is conceded, the achievement remains marvellous. It was an intellectual and diplomatic triumph quite as much as a mere series of successful campaigns; for it required even something more than a soldier of genius to carry the business through. Caesar fought with his brains, utilising the unrivalled knowledge of human weakness and vanity which he had acquired during twenty years of political intrigue at Rome, no less than his military skill. He discovered how to turn to account all the personal and tribal rivalries and jealousies of the Gauls. He knew how to buy and how to retain allies and auxiliaries. He could be a powerful and a liberal friend; but he was also an awe-inspiring enemy. For nothing is more striking in all his career than the way in which this affable and easy-going conqueror had recourse to massacre on the most vast and ruthless scale when he desired to strike terror into his adversaries. The reader of the Commentaries shudders at the callous fashion in which their author narrates his deeds of bloodshed, done not from any feeling of honest resentment but out of cold-blooded policy. The Veneti had placed in bonds (not murdered or tortured) some Roman officers whom Caesar had sent into their territory. For this offence, when they had been attacked and conquered, their whole Senate was put to death, and the rest of the tribe sold as slaves. This was not the worst; there are cases where Caesar puts it on record that his army slew not only the fighting men of a conquered enemy, but the aged, the women, the infants, every living soul.[4] On other occasions he mutilated many thousands of prisoners by cutting off their right hands.[5] Of the case of the Usipetes and Tencteri, whose fate moved horror and compassion even among Romans, we have already had occasion to speak, while dealing with the life of Cato. Nothing can give a more sinister effect than Caesar’s own confession, that he received their ambassadors, who came to explain and apologise for a breach of truce, put them in confinement, and then marched without giving further notice against the unfortunate Germans, whom he surprised unarmed, and cut to pieces — to the number of 430,000 souls, according to the account in the Commentaries. But the most repulsive of all Caesar’s acts of ruthlessness was one which has no parallel for long-delayed and deliberate cruelty, even in the dismal annals of the Later Republic. When the gallant rebel Vercingetorix freely surrendered himself at Alesia to save the lives of his comrades, Caesar would have done nothing strange or improper if he had ordered him to be put to death on the spot. The Arvernian himself expected no less. But for the conqueror to commit him to prison for six years, and then to bring him out at his triumph, parade him through the streets of Rome, and duly execute him in the Tullianum, shows a mixture of callousness and vanity for which no words of reproof are sufficiently hard.

After this, Caesar’s admirers persist in telling us that he was naturally clement;[6] they point to the fact that during the Civil War he very rarely put to death one of his captives,[7] and show that he pardoned some of his most irritating opponents when they fell into his hands. Remembering his awful doings in Gaul, we are driven to believe that his clemency was but a policy or a pose.

Sulla had tried the method of Proscriptions, and it had been a failure. Warned by his experience, Caesar may have made up his mind to adopt the opposite policy in its most complete form. The Ides of March bear witness that this experiment also had its disadvantages. Augustus reverted to the methods of Sulla, but had the art to throw most of the odium on his colleague, Mark Antony.

In the actual details of Caesar’s strategy and tactics in Gaul there is much that is interesting; at first sight they seem to involve some curious puzzles and contradictions. On the one hand he was, of all the great generals whom the world has seen, the one who made the greatest use of the spade. In a single campaign he would throw up more field entrenchments than Napoleon or Hannibal constructed in the whole of their military careers. This tendency is usually the mark of a cautious commander, and has for the most part gone along with slow movements, small risks, and a preference for the defensive. But this same Caesar, who on some occasions stockaded himself up to the eyes, and fortified every inch of ground that he covered, blossomed out at other times into the most reckless ventures. He would fly across the land with marches of almost incredible rapidity, risk undertakings that combined the maximum of danger with the minimum of profit, and stake his whole career on the most audacious strokes, all in the style of Charles XII of Sweden. There is, however, no real incongruity in his actions. It has only to be remembered that his final object was not so much the conquest of Gaul, as the building up for himself of an unrivalled military reputation and a devoted army. His methods differed according to the necessities of the moment, political as well as military, and he was not the slave of any one system of tactics. One does not associate him with any particular order of battle, as we associate Alexander with the advance in échelon with the cavalry leading, or Frederic the Great with his famous “oblique order,” or Napoleon with the intense artillery preparation followed by a blow with heavy columns at one critical point of the adversaries’ line. Caesar was the least monotonous in his tactics of all the great generals whom the world has seen. There is probably in this a trace of the fact that he was essentially an amateur of genius, who had taken to war late in life, and not a soldier steeped from his youth upwards in the study of the drill-book and the manoeuvres of the barrack yard. He worked by the inspiration of the moment, rather than by the aid of the maxims of experience and the traditions of Roman military art.

But, speaking generally, we may say that before he had thoroughly come to know the exact strength and value of his enemy, and when no stake of vital importance was in question, Caesar was usually cautious. In B.C. 58, while he was still new to his legions, and while Gaul and German were still known to him by repute only, he used the spade with untiring energy, and risked as little as he possibly could. His first military act in Gaul was to fortify lines of enormous length against the Helvetii. When he first met Ariovistus he would not stir far from his camp, and entrenched every point that he seized. It was much the same when he made his earliest acquaintance with the Belgae on the Aisne. He checkmated them by his impregnable position, and held them at bay till they dispersed. In the campaign about Alesia, in a similar way, he executed field-works of enormous length and magnitude, making ditch and palisade serve in place of the numbers that were insufficient, because he had not really the force required to perform the double operation of holding Vercingetorix blockaded and of keeping back the army of relief. But even the Alesian circumvallation and contravallation seem small things compared with the interminable lines which Caesar erected along the hills above Dyrrhachium during the campaign of B.C. 48.

When, however, Caesar was driven into a corner, or when he was forced to choose between compromising his reputation and career by a retreat and running a grave risk, he repeatedly staked everything on a single blow. There often arises a moment in war when a commander has to decide between a movement which will be ruinous if it fails, but decisive of the whole campaign if it succeeds, and another which is safe but indecisive. A general who is fighting merely to defend a frontier, or to hold an enemy in check, naturally chooses the latter course. But Caesar, who was aiming at establishing a reputation and winning a dominant position among his fellow-countrymen, often chose to accept the risk; a thoroughly unsuccessful campaign, even if accompanied with no crushing defeat, would have lowered his prestige so much that his career would have been blighted. He preferred rather to hazard everything on a bold stroke: if he had failed, he would probably have chosen not to survive the day. But fortune was ever his friend, and the possible disaster never came, though it was often deserved. Caesar did not talk of his “star” (though his friends invented one for him after his death), but he had more reason to be grateful for unearned pieces of luck than any other great general in the world’s history. He might well have seen his career wrecked when he was surprised by the Nervii on the Sambre, or when he was beset by overwhelming numbers on his march to Samarobriva in B.C. 54, or when the lines of Alesia were all but pierced by the army of Vercassivelaunus. Still nearer was the risk at Dyrrhachium, when, before the arrival of his reinforcements, he seemed doomed to inevitable destruction. At Alexandria the peril was quite as great, and far more gratuitously incurred: indeed the whole Egyptian expedition was reckless almost beyond the bounds of sanity. But fortune never failed Caesar on the battlefield. It seemed that he could not perish by the sword: the dagger was his appointed doom.

In B.C. 50 Gaul lay completely prostrate before the victor’s feet. For the first time he could turn his complete attention to Roman politics, without the fear of being distracted by some dangerous rebellion within his province. This was the greatest of all Caesar’s strokes of luck, for the breach with Pompey and the Senate was clearly at hand, and every man of whom he could dispose would be wanted on the Rubicon. It passes our conception to guess what might have happened if Vercingetorix had but delayed his great rising for two years, and the general revolt of the Gauls had occurred in B.C. 50 instead of in B.C. 52. The declaration of open war by the Optimate party might have reached Caesar at the moment of some check, like that which he suffered before Gergovia, or in the midst of a long protracted siege like that of Alesia. He could never have concentrated his army to march on Italy: it would have been completely tied up in the difficult Gallic operations. Apparently the whole course of the world’s history would have been changed if the Arvernian chief had been a little more dilatory in his organisation of the great national league.

But as things actually went, Caesar was as well prepared for the struggle as he could ever hope to be when the final crisis came. His adversaries had even been good enough to supply him with a plausible casus belli, and to refuse with contumely the many specious proposals for a pacification which he made to them. That he had ever seriously intended that these proposals should be accepted it is hard to believe. In return for a mere permission to stand in his absence for the consulship of B.C. 48, he had offered to give up the Transalpine province and eight of his legions. If the Optimates had accepted the terms, he must either have found some excuse for drawing back from his plighted word, or have been ruined by keeping it. The only possible deduction seems to be that he was well aware that his enemies would refuse every offer, however moderate, which he might make to them. His proposals, therefore, were only intended to influence public opinion, and to cause Cato, Pompey, and their friends to appear in the character of the foes of a reasonable peace. This was the actual result of the negotiations: he was able to pose as a well-meaning citizen, driven into war against his will, and to claim that the passage of the Rubicon was a mere act of self-defence. His ingenious pleas will not stand examination — least of all his solemn complaint that the Optimates had violated the constitution by disregarding the vetoes of his friends, the tribunes Antony and Cassius. To any one who remembers how Caesar himself had treated tribunes and their vetoes during his consulship in B.C. 59, it must appear ludicrous that he should urge this particular grievance against his adversaries.

We have already, when dealing with the life of Pompey, explained the meaning of Caesar’s short and brilliant Italian campaign. He had seen that at this particular moment rapidity was the one chance of success. Without waiting even for his own main body to come up, he had charged down into Italy with headlong speed, and struck his blow before the enemy could mobilise. Not only was he himself in his happiest vein, but fortune was even more propitious than usual, and his adversaries played into his hands. The folly of Domitius wrecked the last chance of the Optimates, and in the short nine weeks between December 16, B.C. 50, and February 20, B.C. 49, he had cleared the enemy out of the whole peninsula. He had seized Rome, whose possession conferred a false air of legality on its master, and at the same time he had occupied the whole recruiting ground where Pompey had intended to raise those legions which were “to start from the earth when he stamped his foot.”

Yet this was but the first act of the drama. Caesar’s position was most precarious: there was a widespread impression that his first success would be followed by massacres, in the style of those by which Marius and Sulla had celebrated their capture of Rome. No one had forgotten that Caesar’s name had once been linked with that of Catiline. To cast a glance around the circle of his lieutenants was anything but reassuring. Assembled around him were all the notorious profligates and bankrupts of the day, Mark Antony and Curio, Caelius and Dolabella, Vatinius and the rest. They were a sinister crowd: Cicero called them the nekyia, the troop of vampires. That any conqueror with such a past as Caesar, surrounded by such a gang of reprobates, could be intending less than wholesale murder and confiscation seemed hardly possible. It took a long time to convince the Romans that they were not to expect “red ruin and the breaking up of laws,” and meanwhile public opinion would have welcomed the return of the respectable Pompey, even though his Optimate friends were certain to make a clean sweep of the Caesarians when they came back victorious.

It was necessary to strike a second blow, as hard as the first had been, if Caesar was to retain what he had won. If he lingered at Rome the seven Pompeian legions from Spain would soon be heard of in the valley of the Po, and Pompey himself, the moment that he had collected a respectable army in Epirus, might descend from his ships on some unexpected point of the Italian seaboard. Caesar had but two advantages — the central position, and the fact that he had a veteran army already mobilised, while his foes were but drawing their levies together. More than most generals he appreciated the value of time. His one chance was to beat his adversaries in detail before they could combine, — even before they could get into communication and settle on a common plan of campaign. It was certain that Pompey could not be ready for many months; on the other hand, the army in Spain was fit to move at once, but was commanded by men whose measure Caesar had taken long before — commonplace soldiers without a stroke of genius. Hence came the dictator’s determination to make a dash at Spain in the spring, with the hope of destroying, or at least of defeating and disabling, Afranius and Petreius, before Pompey could assemble an army in Epirus with which a general of his cautious character would dare to assault Italy.

It was a most hazardous plan, for if Pompey had but risen to the occasion and cast off his methodical ways, he would have found Rome and Italy weakly garrisoned against an attack. But fortune was, as usual, in Caesar’s camp. Afranius and Petreius advanced almost to the foot of the Pyrenees to meet him, and allowed themselves to be out-manoevered, beaten, and taken prisoners at Ilerda (July 2, 49). The Pompeian army of Spain was almost annihilated: only in remote corners of the Iberian peninsula did resistance linger on. Completely freed from the fear of an attack upon his rear by the Pompeians of the West, Caesar could hurry back to Italy to face the Optimate army in Epirus, which was at last growing formidable in numbers, and beginning to acquire a certain military value. It mattered little to him that, while he was victorious at Ilerda, his lieutenant Curio had lost his life and his army while executing a daring but unlucky attack on the Pompeians in Africa.

The Spanish business had been hazardous, for all might have gone wrong for Caesar if only his opponents had refused to fight him, and had adopted guerilla tactics after the fashion of Sertorius. Had they refused battle, and withdrawn into the mountains with their forces intact, Caesar would have been left in a quandary. If he pursued them and was drawn into a long campaign, Italy might well have been lost behind his back. If, on the other hand, he had refused to commit himself to operations in the interior of Spain, and had gone back to Italy with his reserves, he could not have spared an army sufficient to hold back the Pompeian generals. They would have driven in any covering force that he might leave behind, and have once more begun to threaten his rear. But they fought and were annihilated. Again Caesar had been granted the one stroke of fortune that could save him.

Yet he had to hurry from risk to risk. If there had been dangerous possibilities in Spain, those which followed in Epirus were still more threatening. Some of the dangers were of his own making; nothing can excuse the recklessness with which he flung his troops across the sea before he had transports enough to carry them all at one voyage. It was, no doubt, an advantage to be able to cross the straits before Pompey’s admirals, who fancied that all armies must necessarily go into winter quarters in November, had begun to suspect him of any such intention. But the compensating disadvantage of being obliged to leave behind nearly half his army for want of shipping was greater. The second division could not follow him, when the Optimate fleet proceeded to blockade Brundisium. Caesar had to maintain himself in Epirus, with seven weak legions and a handful of cavalry, for nearly three months. By land the superior forces of Pompey held him in check. On the side of the sea he was watched by the squadron which cut his communication with Italy. It was a miracle that he was not destroyed; it required all his good luck to aid his consummate generalship. Once he thought that even his luck had failed him; this was on the occasion when he made his celebrated attempt to run across to Italy in a small open boat, in order to hurry up his reserves at any risk and at all costs. He got out to sea, but his sailors could not face the storm, in spite of his well-known adjuration to them to “fear nothing, for they carried Caesar and his fortunes.” The vessel was beaten back to shore, and the great general had to stave off apparently inevitable disaster for some weeks more, till, in the middle of February, Antony at last succeeded in eluding the Pompeian fleet, and came over to Epirus. How nearly the squadron of the future triumvir came to disaster we have told in an earlier chapter. But after suffering the extreme of peril he reached Epirus and joined his master. Even then the game was not won. There followed the long and well-contested struggle at the lines in front of Dyrrhachium, the most wonderful piece of spade-work in the wars of the ancient world. Modern history has nothing to compare to it except the long contest in 1864-65 between Grant and Lee, in their interminable entrenchments around Richmond and Petersburg, which stretched out to even greater length than those of Caesar and Pompey. But the struggle in Epirus differed in one extraordinary point from the struggle in Virginia; here it was the general with the smaller veteran army who tried to enclose his opponent by running field-works round his flanks and reducing him to starvation. Even Caesar could not carry out such an astonishing plan. He failed with heavy loss, and Pompey broke loose, and seemed for a moment victorious. It was perhaps the greatest of all Caesar’s military achievements that he succeeded in drawing off from his shattered lines without a fatal disaster. But the moment must have been a bitter one to him; it was his first defeat on a large scale, and it was hard to see how it could be retrieved. He had no base on which to retreat, he had no large reinforcements to expect, he was still cut off from Italy by the Pompeian fleet. The sudden march into Thessaly with which he ended the campaign round Dyrrhachium must have been the council of despair. If Pompey failed to follow him into the interior, and chose instead to ship himself over into undefended Italy, the game was lost. Caesar had no fleet in which to follow his rival, and it would have profited him little to take Thessalonica or to ravage Greece.

But once more fortune came to the aid of the great adventurer. Pompey refused to make the bold stroke and to sail for Italy; he followed his enemy across the mountains and offered him battle at Pharsalus. Ruined by the misbehaviour of his numerous cavalry, with which he had hoped to ride down the Gallic legions, he saw his army break and fly, and rode off the field a ruined man.