Editor’s Note: The following comprises the ninth chapter of The Holy Roman Empire, by James Bryce (published 1871). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER IX

SAXON AND FRANCONIAN EMPERORS

He who begins to read the history of the Middle Ages is alternately amused and provoked by the seeming absurdities that meet him at every step. He finds writers proclaiming amidst universal assent magnificent theories which no one attempts to carry out. He sees men who are stained with every vice full of sincere devotion to a religion which, even when its doctrines were most obscured, never sullied the purity of its moral teaching. He is disposed to conclude that such people must have been either fools or hypocrites. Yet such a conclusion would be wholly erroneous. Every one knows how little a man’s actions conform to the general maxims which he would lay down for himself, and how many things there are which he believes without realizing: believes sufficiently to be influenced, yet not sufficiently to be governed by them. Now in the Middle Ages this perpetual opposition of theory and practice was peculiarly abrupt. Men’s impulses were more violent and their conduct more reckless than is often witnessed in modern society; while the absence of a criticizing and measuring spirit made them surrender their minds more unreservedly than they would now do to a complete and imposing theory. Therefore it was, that while everyone believed in the rights of the Empire as a part of divine truth, no one would yield to them where his own passions or interests interfered. Resistance to God’s Vicar might be and indeed was admitted to be a deadly sin, but it was one which nobody hesitated to commit. Hence, in order to give this unbounded imperial prerogative any practical efficiency, it was found necessary to prop it up by the limited but tangible authority of a feudal king. And the one spot in Otto’s empire on which feudality had never fixed its grasp, and where therefore he was forced to rule merely as emperor, and not also as king, was that in which he and his successors were never safe from insult and revolt. That spot was his capital. Accordingly an account of what befel the first Saxon emperor in Rome is a not unfitting comment on the theory expounded above, as well as a curious episode in the history of the Apostolic Chair.

Otto the Great in Rome

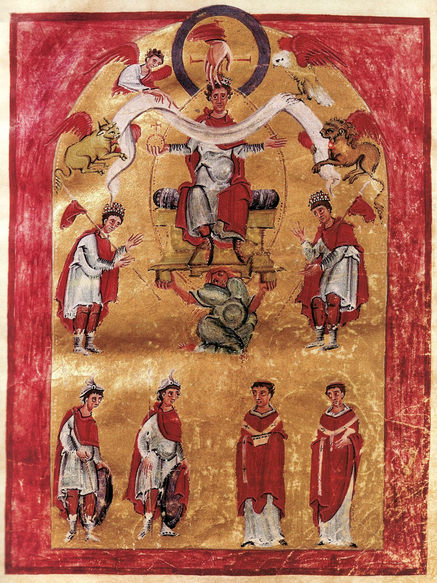

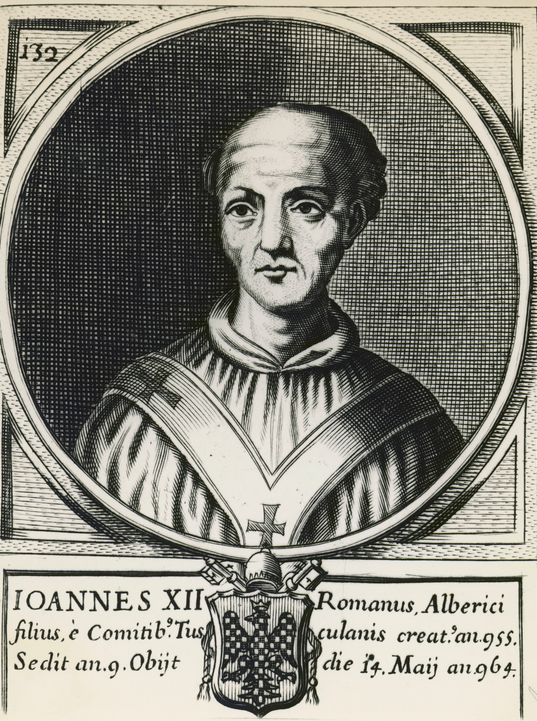

After his coronation Otto had returned to North Italy, where the partizans of Berengar and his son Adalbert still maintained themselves in arms. Scarcely was he gone when the restless John the Twelfth, who found too late that in seeking an ally he had given himself a master, renounced his allegiance, opened negotiations with Berengar, and even scrupled not to send envoys pressing the heathen Magyars to invade Germany. The Emperor was soon informed of these plots, as well as of the flagitious life of the pontiff, a youth of twenty-five, the most profligate if not the most guilty of all who have worn the tiara. But he affected to despise them, saying, with a sort of unconscious irony, ‘He is a boy, the example of good men may reform him.’ When, however, Otto returned with a strong force, he found the city gates shut, and a party within furious against him. John the Twelfth was not only Pope, but as the heir of Alberic, the head of a strong faction among the nobles, and a sort of temporal prince in the city. But neither he nor they had courage enough to stand a siege: John fled into the Campagna to join Adalbert, and Otto entering convoked a synod in St. Peter’s. Himself presiding as temporal head of the Church, he began by inquiring into the character and manners of the Pope. At once a tempest of accusations burst forth from the assembled clergy. Liudprand, a credible although a hostile witness, gives us a long list of them:—’Peter, cardinal-priest, rose and witnessed that he had seen the Pope celebrate mass and not himself communicate. John, bishop of Narnia, and John, cardinal-deacon, declared that they had seen him ordain a deacon in a stable, neglecting the proper formalities. They said further that he had defiled by shameless acts of vice the pontifical palace; that he had openly diverted himself with hunting; had put out the eyes of his spiritual father Benedict; had set fire to houses; had girt himself with a sword, and put on a helmet and hauberk. All present, laymen as well as priests, cried out that he had drunk to the devil’s health; that in throwing the dice he had invoked the help of Jupiter, Venus, and other demons; that he had celebrated matins at uncanonical hours, and had not fortified himself by making the sign of the cross. After these things the Emperor, who could not speak Latin, since the Romans could not understand his native, that is to say, the Saxon tongue, bade Liudprand bishop of Cremona interpret for him, and adjured the council to declare whether the charges they had brought were true, or sprang only of malice and envy. Then all the clergy and people cried with a loud voice, ‘If John the Pope hath not committed all the crimes which Benedict the deacon hath read over, and even greater crimes than these, then may the chief of the Apostles, the blessed Peter, who by his word closes heaven to the unworthy and opens it to the just, never absolve us from our sins, but may we be bound by the chain of anathema, and on the last day may we stand on the left hand along with those who have said to the Lord God, “Depart from us, for we will not know Thy ways.”‘

The solemnity of this answer seems to have satisfied Otto and the council: a letter was despatched to John, couched in respectful terms, recounting the charges brought against him, and asking him to appear to clear himself by his own oath and that of a sufficient number of compurgators. John’s reply was short and pithy.

‘John the bishop, the servant of the servants of God, to all the bishops. We have heard tell that you wish to set up another Pope: if you do this, by Almighty God I excommunicate you, so that you may not have power to perform mass or to ordain no one.’

Deposition of John XII

To this Otto and the synod replied by a letter of humorous expostulation, begging the Pope to reform both his morals and his Latin. But the messenger who bore it could not find John: he had repeated what seems to have been thought his most heinous sin, by going into the country with his bow and arrows; and after a search had been made in vain, the synod resolved to take a decisive step. Otto, who still led their deliberations, demanded the condemnation of the Pope; the assembly deposed him by acclamation, ‘because of his reprobate life,’ and having obtained the Emperor’s consent, proceeded in an equally hasty manner to raise Leo, the chief secretary and a layman, to the chair of the Apostle.

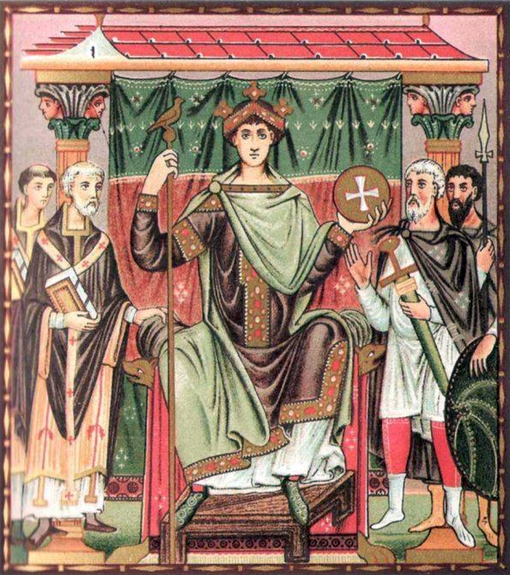

Otto might seem to have now reached a position loftier and firmer than that of any of his predecessors. Within little more than a year from his arrival in Rome, he had exercised powers greater than those of Charles himself, ordering the dethronement of one pontiff and the installation of another, forcing a reluctant people to bend themselves to his will. The submission involved in his oath to protect the Holy See was more than compensated by the oath of allegiance to his crown which the Pope and the Romans had taken, and by their solemn engagement not to elect nor ordain any future pontiff without the Emperor’s consent.

Revolt of the Romans

But he had yet to learn what this obedience and these oaths were worth. The Romans had eagerly joined in the expulsion of John; they soon began to regret him. They were mortified to see their streets filled by a foreign soldiery, the habitual licence of their manners sternly repressed, their most cherished privilege, the right of choosing the universal bishop, grasped by the strong hand of a master who used it for purposes in which they did not sympathize. In a fickle and turbulent people, disaffection quickly turned to rebellion. One night, Otto’s troops being most of them dispersed in their quarters at a distance, the Romans rose in arms, blocked up the Tiber bridges, and fell furiously upon the Emperor and his creature the new Pope. Superior valour and constancy triumphed over numbers, and the Romans were overthrown with terrible slaughter; yet this lesson did not prevent them from revolting a second time, after Otto’s departure in pursuit of Adalbert. John the Twelfth returned to the city, and when his pontifical career was speedily closed by the sword of an injured husband, the people chose a new Pope in defiance of the Emperor and his nominee. Otto again subdued and again forgave them, but when they rebelled for a third time, in A.D. 966, he resolved to shew them what imperial supremacy meant. Thirteen leaders, among them the twelve tribunes, were executed, the consuls were banished, republican forms entirely suppressed, the government of the city entrusted to Pope Leo as viceroy. He, too, must not presume on the sacredness of his person to set up any claims to independence. Otto regarded the pontiff as no more than the first of his subjects, the creature of his own will, the depositary of an authority which must be exercised according to the discretion of his sovereign. The citizens yielded to the Emperor an absolute veto on papal elections in A.D. 963. Otto obtained from his nominee, Leo VIII, a confirmation of this privilege, which it was afterwards supposed that Hadrian I had granted to Charles, in a decree which may yet be read in the collections of the canon law. The vigorous exercise of such a power might be expected to reform as well as to restrain the apostolic see; and it was for this purpose, and in noble honesty, that the Teutonic sovereigns employed it. But the fortunes of Otto in the city are a type of those which his successors were destined to experience. Notwithstanding their clear rights and the momentary enthusiasm with which they were greeted in Rome, not all the efforts of Emperor after Emperor could gain any firm hold on the capital they were so proud of. Visiting it only once or twice in their reigns, they must be supported among a fickle populace by a large army of strangers, which melted away with terrible rapidity under the sun of Italy amid the deadly hollows of the Campagna. Rome soon resumed her turbulent independence.

Otto’s rule in Italy

Causes partly the same prevented the Saxon princes from gaining a firm footing throughout Italy. Since Charles the Bald had bartered away for the crown all that made it worth having, no Emperor had exercised substantial authority there. The missi dominici had ceased to traverse the country; the local governors had thrown off control, a crowd of petty potentates had established principalities by aggressions on their weaker neighbours. Only in the dominions of great nobles, like the marquises of Tuscany and Spoleto, and in some of the cities where the supremacy of the bishop was paving the way for a republican system, could traces of political order be found, or the arts of peace flourish. Otto, who, though he came as a conqueror, ruled legitimately as Italian king, found his feudal vassals less submissive than in Germany. While actually present he succeeded by progresses and edicts, and stern justice, in doing something to still the turmoil; on his departure Italy relapsed into that disorganization for which her natural features are not less answerable than the mixture of her races. Yet it was at this era, when the confusion was wildest, that there appeared the first rudiments of an Italian nationality, based partly on geographical position, partly on the use of a common language and the slow growth of peculiar customs and modes of thought. But though already jealous of the Tedescan, national feeling was still very far from disputing his sway. Pope, princes, and cities bowed to Otto as king and Emperor; nor did he bethink himself of crushing while it was weak a sentiment whose development threatened the existence of his empire. Holding Italy equally for his own with Germany, and ruling both on the same principles, he was content to keep it a separate kingdom, neither changing its institutions nor sending Saxons, as Charles had sent Franks, to represent his government.

Otto’s foreign policy

The lofty claims which Otto acquired with the Roman crown urged him to resume the plans of foreign conquest which had lain neglected since the days of Charles: the growing vigour of the Teutonic people, now definitely separating themselves from surrounding races (this is the era of the Marks—Brandenburg, Meissen, Schleswig), placed in his hands a force to execute those plans which his predecessors had wanted. In this, as in his other enterprises, the great Emperor was active, wise, successful.

Towards Byzantium

Retaining the extreme south of Italy, and unwilling to confess the loss of Rome, the Greeks had not ceased to annoy her German masters by intrigue, and might now, under the vigorous leadership of Nicephorus and Tzimiskes, hope again to menace them in arms. Policy, and the fascination which an ostentatiously legitimate court exercised over the Saxon stranger, made Otto, as Napoleon wooed Maria Louisa, seek for his heir the hand of the princess Theophano. Liudprand’s account of his embassy represents in an amusing manner the rival pretensions of the old and new Empires. The Greeks, who fancied that with the name they preserved the character and rights of Rome, held it almost as absurd as it was wicked that a Frank should insult their prerogative by reigning in Italy as Emperor. They refused him that title altogether; and when the Pope had, in a letter addressed ‘Imperatori Græcorum,’ asked Nicephorus to gratify the wishes of the Emperor of the Romans, the Eastern was furious. ‘You are no Romans,’ said he, ‘but wretched Lombards: what means this insolent Pope? With Constantine all Rome migrated hither.’ The wily bishop appeased him by abusing the Romans, while he insinuated that Byzantium could lay no claim to their name, and proceeded to vindicate the Francia and Saxonia of his master. ‘”Roman” is the most contemptuous name we can use—it conveys the reproach of every vice, cowardice, falsehood, avarice. But what can be expected from the descendants of the fratricide Romulus? To his asylum were gathered the offscourings of the nations: thence came these κοσμοκράτορες.’ [kosmokratores: world rulers – ed.]. Nicephorus demanded the ‘theme’ or province of Rome as the price of compliance; Tzimiskes was more moderate, and Theophano became the bride of Otto II.

Towards the West Franks

Holding the two capitals of Charles the Great, Otto might vindicate the suzerainty over the West Frankish kingdom which it had been meant that the imperial title should carry with it. Arnulf had asserted it by making Eudes, the first Capetian king, receive the crown as his feudatory: Henry the Fowler had been less successful. Otto pursued the same course, intriguing with the discontented nobles of Louis d’Outremer, and receiving their fealty as Superior of Roman Gaul. These pretensions, however, could have been made effective only by arms, and the feudal militia of the tenth century was no such instrument of conquest as the hosts of Clovis and Charles had been. The star of the Carolingian of Laon was paling before the rising greatness of the Parisian Capets: a Romano-Keltic nation had formed itself, distinct in tongue from the Franks, whom it was fast absorbing, and still less willing to submit to a Saxon stranger. Modern France dates from the accession of Hugh Capet, A.D. 987, and the claims of the Roman Empire were never afterwards formally admitted.

Lorraine and Burgundy

Of that France, however, Aquitaine was virtually independent. Lotharingia and Burgundy belonged to it as little as did England. The former of these kingdoms had adhered to the West Frankish king, Charles the Simple, against the East Frankish Conrad: but now, as mostly German in blood and speech, threw itself into the arms of Otto, and was thenceforth an integral part of the Empire. Burgundy, a separate kingdom, had, by seeking from Charles the Fat a ratification of Boso’s election, by admitting, in the person of Rudolf the first Transjurane king, the feudal superiority of Arnulf, acknowledged itself to be dependent on the German crown. Otto governed it for thirty years, nominally as the guardian of the young king Conrad (son of Rudolf II).

Denmark and the Slavs

Otto’s conquests to the North and East approved him a worthy successor of the first Emperor. He penetrated far into Jutland, annexed Schleswig, made Harold the Blue-toothed his vassal. The Slavic tribes were obliged to submit, to follow the German host in war, to allow the free preaching of the Gospel in their borders. The Hungarians he forced to forsake their nomad life, and delivered Europe from the fear of Asiatic invasions by strengthening the frontier of Austria.

England

Over more distant lands, Spain and England, it was not possible to recover the commanding position of Charles. Henry, as head of the Saxon name, may have wished to unite its branches on both sides the sea, and it was perhaps partly with this intent that he gained for Otto the hand of Edith, sister of the English Athelstan. But the claim of supremacy, if any there was, was repudiated by Edgar, when, exaggerating the lofty style assumed by some of his predecessors, he called himself ‘Basileus and imperator of Britain,’ thereby seeming to pretend to a sovereignty over all the nations of the island similar to that which the Roman Emperor claimed over the states of Christendom.

Extent of Otto’s Empire

This restored Empire, which professed itself a continuation of the Carolingian, was in many respects different. It was less wide, including, if we reckon strictly, only Germany proper and two-thirds of Italy; or counting in subject but separate kingdoms, Burgundy, Bohemia, Moravia, Poland, Denmark, perhaps Hungary.

Comparison between it and that of Charles

Its character was less ecclesiastical. Otto exalted indeed the spiritual potentates of his realm, and was earnest in spreading Christianity among the heathen: he was master of the Pope and Defender of the Holy Roman Church. But religion held a less important place in his mind and his administration: he made fewer wars for its sake, held no councils, and did not, like his predecessor, criticize the discourses of bishops. It was also less Roman. We do not know whether Otto associated with that name anything more than the right to universal dominion and a certain oversight of matters spiritual, nor how far he believed himself to be treading in the steps of the Cæsars. He could not speak Latin, he had few learned men around him, he cannot have possessed the varied cultivation which had been so fruitful in the mind of Charles. Moreover, the conditions of his time were different, and did not permit similar attempts at wide organization. The local potentates would have submitted to no missi dominici; separate laws and jurisdictions would not have yielded to imperial capitularies; the placita at which those laws were framed or published would not have been crowded, as of yore, by armed freemen. But what Otto could he did, and did it to good purpose. Constantly traversing his dominions, he introduced a peace and prosperity before unknown, and left everywhere the impress of an heroic character. Under him the Germans became not only a united nation, but were at once raised on a pinnacle among European peoples as the imperial race, the possessors of Rome and Rome’s authority. While the political connection with Italy stirred their spirit, it brought with it a knowledge and culture hitherto unknown, and gave the newly-kindled energy an object. Germany became in her turn the instructress of the neighbouring tribes, who trembled at Otto’s sceptre; Poland and Bohemia received from her their arts and their learning with their religion. If the revived Romano-Germanic Empire was less splendid than the Empire of the West had been under Charles, it was, within narrower limits, firmer and more lasting, since based on a social force which the other had wanted. It perpetuated the name, the language, the literature, such as it then was, of Rome; it extended her spiritual sway; it strove to represent that concentration for which men cried, and became a power to unite and civilize Europe.

Otto II, A.D. 973-983 / Otto III, A.D. 983-1002

The time of Otto the Great has required a fuller treatment, as the era of the Holy Empire’s foundation: succeeding rulers may be more quickly dismissed. Yet Otto III’s reign cannot pass unnoticed: short, sad, full of bright promise never fulfilled.

His ideas. Fascination exercised over him by the name of Rome.

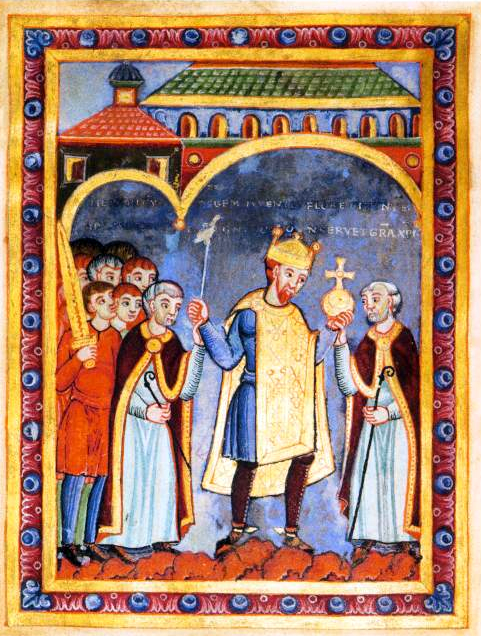

His mother was the Greek princess Theophano; his preceptor, the illustrious Gerbert: through the one he felt himself connected with the old Empire, and had imbibed the absolutism of Byzantium; by the other he had been reared in the dream of a renovated Rome, with her memories turned to realities. To accomplish that renovation, who so fit as he who with the vigorous blood of the Teutonic conqueror inherited the venerable rights of Constantinople? It was his design, now that the solemn millennial era of the founding of Christianity had arrived, to renew the majesty of the city and make her again the capital of a world-embracing Empire, victorious as Trajan’s, despotic as Justinian’s, holy as Constantine’s. His young and visionary mind was too much dazzled by the gorgeous fancies it created to see the world as it was: Germany rude, Italy unquiet, Rome corrupt and faithless. In A.D. 994, at the age of sixteen, he took from his mother’s hands the reins of government, and entered Italy to receive his crown, and quell the turbulence of Rome. There he put to death the rebel Crescentius, in whom modern enthusiasm has seen a patriotic republican, who, reviving the institutions of Alberic, had ruled as consul or senator, sometimes entitling himself Emperor.

Pope Sylvester II, A.D. 1000

The young monarch reclaimed, perhaps extended, the privilege of Charles and Otto the Great, by nominating successive pontiffs: first Bruno his cousin (Gregory V), then Gerbert, whose name of Sylvester II recalled significantly the ally of Constantine: Gerbert, to his contemporaries a marvel of piety and learning, in later legend the magician who, at the price of his own soul, purchased preferment from the Enemy, and by him was at last carried off in the body. With the substitution of these men for the profligate priests of Italy, began that Teutonic reform of the Papacy which raised it from the abyss of the tenth century to the point where Hildebrand found it. The Emperors were working the ruin of their power by their most disinterested acts.

Schemes of Otto III: Changes of style and usage

With his tutor on Peter’s chair to second or direct him, Otto laboured on his great project in a spirit almost mystic. He had an intense religious belief in the Emperor’s duties to the world—in his proclamations he calls himself ‘Servant of the Apostles,’ ‘Servant of Jesus Christ’—together with the ambitious antiquarianism of a fiery imagination, kindled by the memorials of the glory and power he represented. Even the wording of his laws witnesses to the strange mixture of notions that filled his eager brain. ‘We have ordained this,’ says an edict, ‘in order that, the church of God being freely and firmly stablished, our Empire may be advanced and the crown of our knighthood triumph; that the power of the Roman people may be extended and the commonwealth be restored; so may we be found worthy after living righteously in the tabernacle of this world, to fly away from the prison of this life and reign most righteously with the Lord.’ To exclude the claims of the Greeks he used the title ‘Romanorum Imperator‘ instead of the simple ‘Imperator‘ of his predecessors. His seals bear a legend resembling that used by Charles, ‘Renovatio Imperii Romanorum;’ even the ‘commonwealth,’ despite the results that name had produced under Alberic and Crescentius, was to be re-established. He built a palace on the Aventine, then the most healthy and beautiful quarter of the city; he devised a regular administrative system of government for his capital—naming a patrician, a prefect, and a body of judges, who were commanded to recognize no law but Justinian’s. The formula of their appointment has been preserved to us: in it the Emperor delivering to the judge a copy of the code bids him ‘with this code judge Rome and the Leonine city and the whole world.’ He introduced into the simple German court the ceremonious magnificence of Byzantium, not without giving offence to many of his followers. His father’s wish to draw Italy and Germany more closely together, he followed up by giving the chancellorship of both countries to the same churchman, by maintaining a strong force of Germans in Italy, and by taking his Italian retinue with him through the Transalpine lands. How far these brilliant and far-reaching plans were capable of realization, had their author lived to attempt it, can be but guessed at. It is reasonable to suppose that whatever power he might have gained in the South he would have lost in the North. Dwelling rarely in Germany, and in sympathies more a Greek than a Teuton, he reined in the fierce barons with no such tight hand as his grandfather had been wont to do; he neglected the schemes of northern conquest; he released the Polish dukes from the obligation of tribute. But all, save that those plans were his, is now no more than conjecture, for Otto III, ‘the wonder of the world,’ as his own generation called him, died childless on the threshold of manhood; the victim, if we may trust a story of the time, of the revenge of Stephania, widow of Crescentius, who ensnared him by her beauty, and slew him by a lingering poison. They carried him across the Alps with laments whose echoes sound faintly yet from the pages of monkish chroniclers, and buried him in the choir of the basilica at Aachen some fifty paces from the tomb of Charles beneath the central dome. Two years had not passed since, setting out on his last journey to Rome, he had opened that tomb, had gazed on the great Emperor, sitting on a marble throne, robed and crowned, with the Gospel-book open before him; and there, touching the dead hand, unclasping from the neck its golden cross, had taken, as it were, an investiture of Empire from his Frankish forerunner. Short as was his life and few his acts, Otto III is in one respect more memorable than any who went before or came after him. None save he desired to make the seven-hilled city again the seat of dominion, reducing Germany and Lombardy and Greece to their rightful place of subject provinces. No one else so forgot the present to live in the light of the ancient order; no other soul was so possessed by that fervid mysticism and that reverence for the glories of the past, whereon rested the idea of the mediæval Empire.

Italy independent

The direct line of Otto the Great had now ended, and though the Franks might elect and the Saxons accept Henry II, Italy was nowise affected by their acts. Neither the Empire nor the Lombard kingdom could as yet be of right claimed by the German king. Her princes placed Ardoin, marquis of Ivrea, on the vacant throne of Pavia, moved partly by the growing aversion to a Transalpine power, still more by the desire of impunity under a monarch feebler than any since Berengar. But the selfishness that had exalted Ardoin soon overthrew him.

Henry II Emperor

Ere long a party among the nobles, seconded by the Pope, invited Henry; his strong army made opposition hopeless, and at Rome he received the imperial crown, A.D. 1014. It is, perhaps, more singular that the Transalpine kings should have clung so pertinaciously to Italian sovereignty than that the Lombards should have so frequently attempted to recover their independence. For the former had often little or no hereditary claim, they were not secure in their seat at home, they crossed a huge mountain barrier into a land of treachery and hatred. But Rome’s glittering lure was irresistible, and the disunion of Italy promised an easy conquest. Surrounded by martial vassals, these Emperors were generally for the moment supreme: once their pennons had disappeared in the gorges of Tyrol, things reverted to their former condition, and Tuscany was little more dependent than France.

Southern Italy

In Southern Italy the Greek viceroy ruled from Bari, and Rome was an outpost instead of the centre of Teutonic power. A curious evidence of the wavering politics of the time is furnished by the Annals of Benevento, the Lombard town which on the confines of the Greek and Roman realms gave steady obedience to neither. They usually date by and recognize the princes of Constantinople, seldom mentioning the Franks, till the reign of Conrad II; after him the Western becomes Imperator, the Greek, appearing more rarely, is Imperator Constantinopolitanus. Assailed by the Saracens, masters already of Sicily, these regions seemed on the eve of being lost to Christendom, and the Romans sometimes bethought themselves of returning under the Byzantine sceptre. As the weakness of the Greeks in the South favoured the rise of the Norman kingdom, so did the liberties of the northern cities shoot up in the absence of the Emperors and the feuds of the princes. Milan, Pavia, Cremona, were only the foremost among many populous centres of industry, some of them self-governing, all quickly absorbing or repelling the rural nobility, and not afraid to display by tumults their aversion to the Germans.

Conrad II

The reign of Conrad II, the first monarch of the great Franconian line, is remarkable for the accession to the Empire of Burgundy, or, as it is after this time more often called, the kingdom of Arles. Rudolf III, the last king, had proposed to bequeath it to Henry II, and the states were at length persuaded to consent to its reunion to the crown from which it had been separated, though to some extent dependent, since the death of Lothar I (son of Lewis the Pious). On Rudolf’s death in 1032, Eudes, count of Champagne, endeavoured to seize it, and entered the north-western districts, from which he was dislodged by Conrad with some difficulty. Unlike Italy, it became an integral member of the Germanic realm: its prelates and nobles sat in imperial diets, and retained till recently the style and title of Princes of the Holy Empire. The central government was, however, seldom effective in these outlying territories, exposed always to the intrigues, finally to the aggressions, of Capetian France.

Henry III

Under Conrad’s son Henry the Third the Empire attained the meridian of its power. At home Otto the Great’s prerogative had not stood so high. The duchies, always the chief source of fear, were allowed to remain vacant or filled by the relatives of the monarch, who himself retained, contrary to usual practice, those of Franconia and (for some years) Swabia. Abbeys and sees lay entirely in his gift. Intestine feuds were repressed by the proclamation of a public peace. Abroad, the feudal superiority over Hungary, which Henry II had gained by conferring the title of King with the hand of his sister Gisela, was enforced by war, the country made almost a province, and compelled to pay tribute.

His reform of the Popedom

In Rome no German sovereign had ever been so absolute. A disgraceful contest between three claimants of the papal chair had shocked even the reckless apathy of Italy. Henry deposed them all, and appointed their successor: he became hereditary patrician, and wore constantly the green mantle and circlet of gold which were the badges of that office, seeming, one might think, to find in it some further authority than that which the imperial name conferred. The synod passed a decree granting to Henry the right of nominating the supreme pontiff; and the Roman priesthood, who had forfeited the respect of the world even more by habitual simony than by the flagrant corruption of their manners, were forced to receive German after German as their bishop, at the bidding of a ruler so powerful, so severe, and so pious.

Henry IV, A.D. 1056-1106

But Henry’s encroachments alarmed his own nobles no less than the Italians, and the reaction, which might have been dangerous to himself, was fatal to his successor. A mere chance, as some might call it, determined the course of history. The great Emperor died suddenly in A.D. 1056, and a child was left at the helm, while storms were gathering that might have demanded the wisest hand.