Editor’s Note: The following comprises the sixth chapter of The Holy Roman Empire, by James Bryce (published 1871). All spelling in the original.

(Continued from Part 5)

CHAPTER VI

CAROLINGIAN AND ITALIAN EMPERORS

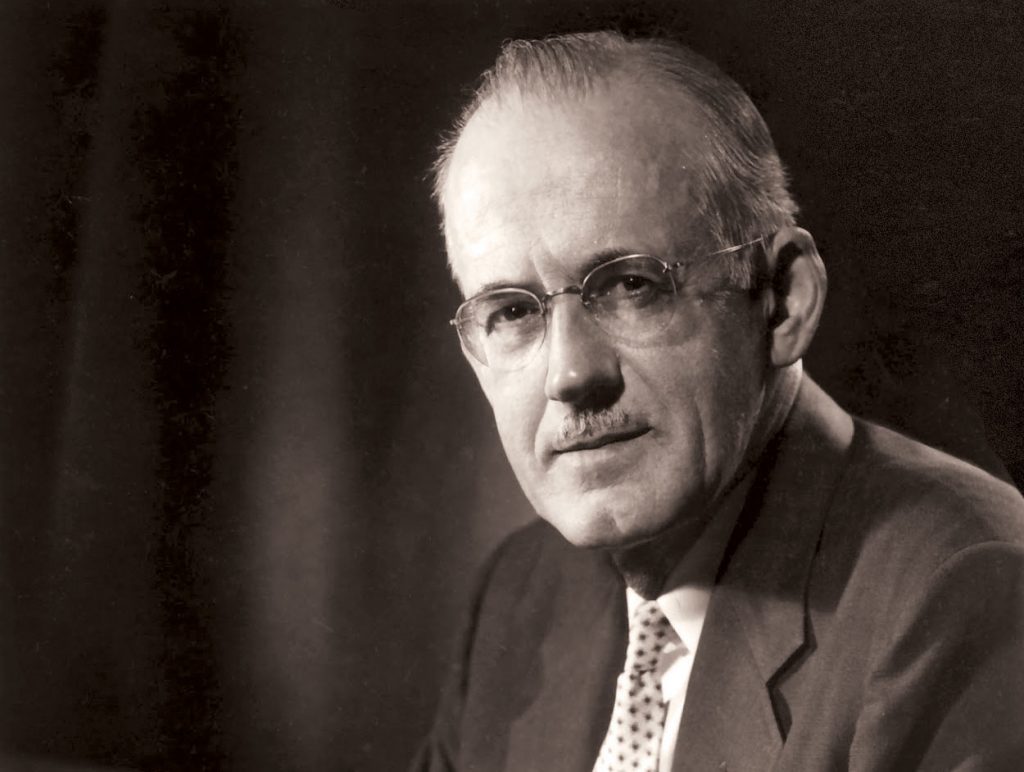

Lewis the Pious

Lewis the Pious, left by Charles’s death sole heir, had been some years before associated with his father in the Empire, and had been crowned by his own hands in a way which, intentionally or not, appeared to deny the need of Papal sanction. But it was soon seen that the strength to grasp the sceptre had not passed with it. Too mild to restrain his turbulent nobles, and thrown by over-conscientiousness into the hands of the clergy, he had reigned few years when dissensions broke out on all sides. Charles had wished the Empire to continue one, under the supremacy of a single Emperor, but with its several parts, Lombardy, Aquitaine, Austrasia, Bavaria, each a kingdom held by a scion of the reigning house. A scheme dangerous in itself, and rendered more so by the absence or neglect of regular rules of succession, could with difficulty have been managed by a wise and firm monarch. Lewis tried in vain to satisfy his sons (Lothar, Lewis, and Charles) by dividing and redividing: they rebelled; he was deposed, and forced by the bishops to do penance; again restored, but without power, a tool in the hands of contending factions. On his death the sons flew to arms, and the first of the dynastic quarrels of modern Europe was fought out on the field of Fontenay.

Partition of Verdun, A.D. 843

In the partition treaty of Verdun which followed, the Teutonic principle of equal division among heirs triumphed over the Roman one of the transmission of an indivisible Empire: the practical sovereignty of all three brothers was admitted in their respective territories, a barren precedence only reserved to Lothar, with the imperial title which he, as the eldest, already enjoyed. A more important result was the separation of the Gaulish and German nationalities. Their difference of feeling, shewn already in the support of Lewis the Pious by the Germans against the Gallo-Franks and the Church, took now a permanent shape: modern Germany proclaims the era of A.D. 843 the beginning of her national existence, and celebrated its thousandth anniversary twenty-seven years ago. To Charles the Bald was given Francia Occidentalis, that is to say, Neustria and Aquitaine; to Lothar, who as Emperor must possess the two capitals, Rome and Aachen, a long and narrow kingdom stretching from the North Sea to the Mediterranean, and including the northern half of Italy: Lewis (surnamed, from his kingdom, the German) received all east of the Rhine, Franks, Saxons, Bavarians, Austria, Carinthia, with possible supremacies over Czechs and Moravians beyond. Throughout these regions German was spoken; through Charles’s kingdom a corrupt tongue, equally removed from Latin and from modern French. Lothar’s, being mixed and 78 having no national basis, was the weakest of the three, and soon dissolved into the separate sovereignties of Italy, Burgundy, and Lotharingia, or, as we call it, Lorraine.

End of the Carolingian Empire of the West, A.D. 888

On the tangled history of the period that follows it is not possible to do more than touch. After passing from one branch of the Carolingian line to another, the imperial sceptre was at last possessed and disgraced by Charles the Fat, who united all the dominions of his great-grandfather. This unworthy heir could not avail himself of recovered territory to strengthen or defend the expiring monarchy. He was driven out of Italy in A.D. 887, and his death in 888 has been usually taken as the date of the extinction of the Carolingian Empire of the West. The Germans, still attached to the ancient line, chose Arnulf, an illegitimate Carolingian, for their king: he entered Italy and was crowned Emperor by his partizan Pope Formosus, in 894. But Germany, divided and helpless, was in no condition to maintain her power over the southern lands: Arnulf retreated in haste, leaving Rome and Italy to sixty years of stormy independence.

That time was indeed the nadir of order and civilization. From all sides the torrent of barbarism which Charles the Great had stemmed was rushing down upon his empire. The Saracen wasted the Mediterranean coasts, and sacked Rome herself. The Dane and Norseman swept the Atlantic and the North Sea, pierced France and Germany by their rivers, burning, slaying, carrying off into captivity: pouring through the Straits of Gibraltar, they fell upon Provence and Italy. By land, while Wends and Czechs and Obotrites threw off the German yoke and threatened the borders, the wild Hungarian bands, pressing in from the steppes of the Caspian, dashed over Germany like the flying spray of a new wave of barbarism, and carried the terror of their battleaxes to the Apennines and the ocean. Under such strokes the already loosened fabric swiftly dissolved. No one thought of common defence or wide organization: the strong built castles, the weak became their bondsmen, or took shelter under the cowl: the governor—count, abbot, or bishop—tightened his grasp, turned a delegated into an independent, a personal into a territorial authority, and hardly owned a distant and feeble suzerain. The grand vision of a universal Christian empire was utterly lost in the isolation, the antagonism, the increasing localization of all powers: it might seem to have been but a passing gleam from an older and better world.

The German Kingdom

In Germany, the greatness of the evil worked at last its cure. When the male line of the eastern branch of the Carolingians had ended in Lewis (surnamed the Child), son of Arnulf, the chieftains chose and the people accepted Conrad the Franconian, and after him Henry the Saxon duke, both representing the female line of Charles.

Henry the Fowler

Henry laid the foundations of a firm monarchy, driving back the Magyars and Wends, recovering Lotharingia, founding towns to be centres of orderly life and strongholds against Hungarian irruptions. He had meant to claim at Rome his kingdom’s rights, rights which Conrad’s weakness had at least asserted by the demand of tribute; but death overtook him, and the plan was left to be fulfilled by Otto his son.

Otto the Great

The Holy Roman Empire, taking the name in the sense which it commonly bore in later centuries, as denoting the sovereignty of Germany and Italy vested in a Germanic prince, is the creation of Otto the Great. Substantially, it is true, as well as technically, it was a prolongation of the Empire of Charles; and it rested (as will be shewn in the sequel) upon ideas essentially the same as those which brought about the coronation of A.D. 800. But a revival is always more or less a revolution: the one hundred and fifty years that had passed since the death of Charles had brought with them changes which made Otto’s position in Germany and Europe less commanding and less autocratic than his predecessor’s. With narrower geographical limits, his Empire had a less plausible claim to be the heir of Rome’s universal dominion; and there were also differences in its inner character and structure sufficient to justify us in considering Otto (as he is usually considered by his countrymen) not a mere successor after an interregnum, but rather a second founder of the imperial throne in the West.

Before Otto’s descent into Italy is described, something must be said of the condition of that country, where circumstances had again made possible the plan of Theodoric, permitted it to become an independent kingdom, and attached the imperial title to its sovereign.

Italian Emperors

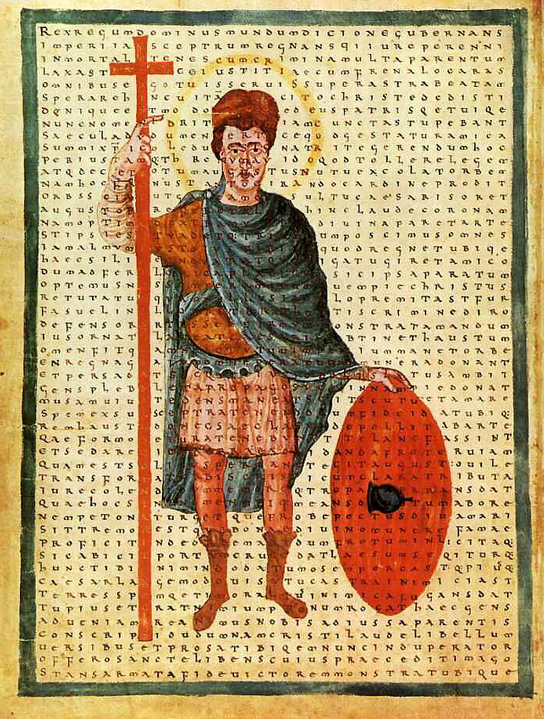

The bestowal of the purple on Charles the Great was not really that ‘translation of the Empire from the Greeks to the Franks,’ which it was afterwards described as having been. It was not meant to settle the office in one nation or one dynasty: there was but an extension of that principle of the equality of all Romans which had made Trajan and Maximin Emperors. The ‘arcanum imperii,’ whereof Tacitus speaks, ‘posse principem alibi quam Romæ fieri,’ had long before become alium quam Romanum; and now, the names of Roman and Christian having grown co-extensive, a barbarian chieftain was, as a Roman citizen, eligible to the office of Roman Emperor. Treating him as such, the people and pontiff of the capital had in the vacancy of the Eastern throne asserted their ancient rights of election, and while attempting to reverse the act of Constantine, had re-established the division of Valentinian. The dignity was therefore in strictness personal to Charles; in point of fact, and by consent, hereditarily transmissible, just as it had formerly become in the families of Constantine and Theodosius. To the Frankish crown or nation it was by no means legally attached, though they might think it so; it had passed to their king only because he was the greatest European potentate, and might equally well pass to some stronger race, if any such appeared. Hence, when the line of Carolingian Emperors ended in Charles the Fat, the rights of Rome and Italy might be taken to revive, and there was nothing to prevent the citizens from choosing whom they would. At that memorable era (A.D. 888) the four kingdoms which this prince had united fell asunder; West France, where Odo or Eudes then began to reign, was never again united to Germany; East France (Germany) chose Arnulf; Burgundy split up into two principalities, in one of which (Transjurane) Rudolf proclaimed himself king, while the other (Cisjurane with Provence) submitted to Boso; while Italy was divided between the parties of Berengar of Friuli and Guido of Spoleto. The former was chosen king by the estates of Lombardy; the latter, and on his speedy death his son Lambert, was crowned Emperor by the Pope. Arnulf’s descent chased them away and vindicated the claims of the Franks, but on his flight Italy and the anti-German faction at Rome became again free. Berengar was made king of Italy, and afterwards Emperor. Lewis of Burgundy, son of Boso, renounced his fealty to Arnulf, and procured the imperial dignity, whose vain title he retained through years of misery and exile, till A.D. 928. None of these Emperors were strong enough to rule well even in Italy; beyond it they were not so much as recognized. The crown had become a bauble with which unscrupulous Popes dazzled the vanity of princes whom they summoned to their aid, and soothed the credulity of their more honest supporters. The demoralization and confusion of Italy, the shameless profligacy of Rome and her pontiffs during this period, were enough to prevent a true Italian kingdom from being built up on the basis of Roman choice and national unity. Italian indeed it can scarcely be called, for these Emperors were still in blood and manners Teutonic, and akin rather to their Transalpine enemies than their Romanic subjects. But Italian it might soon have become under a vigorous rule which should have organized it within and knit it together to resist attacks from without. And therefore the attempt to establish such a kingdom is remarkable, for it might have had great consequences; might, if it had prospered, have spared Italy much suffering and Germany endless waste of strength and blood. He who from the summit of Milan cathedral sees across the misty plain the gleaming turrets of its icy wall sweep in a great arc from North to West, may well wonder that a land which nature has so severed from its neighbours should, since history begins, have been always the victim of their intrusive tyranny.

Adelheid Queen of Italy

In A.D. 924 died Berengar, the last of these phantom Emperors. After him Hugh of Burgundy, and Lothar his son, reigned as kings of Italy, if puppets in the hands of a riotous aristocracy can be so called. Rome was meanwhile ruled by the consul or senator Alberic, who had renewed her never quite extinct republican institutions, and in the degradation of the papacy was almost absolute in the city. Lothar dying, his widow Adelheid was sought in marriage by Adalbert son of Berengar II, the new Italian monarch. A gleam of romance is shed on the Empire’s revival by her beauty and her adventures. Rejecting the odious alliance, she was seized by Berengar, escaped with difficulty from the loathsome prison where his barbarity had confined her, and appealed to Otto the German king, the model of that knightly virtue which was beginning to shew itself after the fierce brutality of the last age.

Otto’s first expedition into Italy, A.D. 951 / Invitation sent by the Pope to Otto

He listened, descended into Lombardy by the Adige valley, espoused the injured queen, and forced Berengar to hold his kingdom as a vassal of the East Frankish crown. That prince was turbulent and faithless; new complaints reached ere long his liege lord, and envoys from the Pope offered Otto the imperial title if he would re-visit and pacify Italy.

Motives for reviving the Empire

The proposal was well-timed. Men still thought, as they had thought in the centuries before the Carolingians, that the Empire was suspended, not extinct; and the desire to see its effective power restored, the belief that without it the world could never be right, might seem better grounded than it had been before the coronation of Charles. Then the imperial name had recalled only the faint memories of Roman majesty and order; now it was also associated with the golden age of the first Frankish Emperor, when a single firm and just hand had guided the state, reformed the church, repressed the excesses of local power: when Christianity had advanced against heathendom, civilizing as she went, fearing neither Hun nor Paynim. One annalist tells us that Charles was elected ‘lest the pagans should insult the Christians, if the name of Emperor should have ceased among the Christians.’ The motive would be bitterly enforced by the calamities of the last fifty years. In a time of disintegration, confusion, strife, all the longings of every wiser and better soul for unity, for peace and law, for some bond to bring Christian men and Christian states together against the common enemy of the faith, were but so many cries for the restoration of the Roman Empire. These were the feelings that on the field of Merseburg broke forth in the shout of ‘Henry the Emperor:’ these the hopes of the Teutonic host when after the great deliverance of the Lechfeld they greeted Otto, conqueror of the Magyars, as ‘Imperator Augustus, Pater Patriæ.’

Condition of Italy

The anarchy which an Emperor was needed to heal was at its worst in Italy, desolated by the feuds of a crowd of petty princes. A succession of infamous Popes, raised by means yet more infamous, the lovers and sons of Theodora and Marozia, had disgraced the chair of the Apostle, and though Rome herself might be lost to decency, Western Christendom was roused to anger and alarm. Men had not yet learned to satisfy their consciences by separating the person from the office. The rule of Alberic had been succeeded by the wildest confusion, and demands were raised for the renewal of that imperial authority which all admitted in theory, and which nothing but the resolute opposition of Alberic himself had prevented Otto from claiming in 951. From the Byzantine Empire, whither Italy was more than once tempted to turn, nothing could be hoped; its dangers from foreign enemies were aggravated by the plots of the court and the seditions of the capital; it was becoming more and more alienated from the West by the Photian schism and the question regarding the Procession of the Holy Ghost, which that quarrel had started. Germany was extending and consolidating herself, had escaped domestic perils, and might think of reviving ancient claims. No one could be more willing to revive them than Otto the Great. His ardent spirit, after waging a bold and successful struggle against the turbulent magnates of his German realm, had engaged him in wars with the surrounding nations, and was now captivated by the vision of a wider sway and a loftier world-embracing dignity. Nor was the prospect which the papal offer opened up less welcome to his people. Aachen, their capital, was the ancestral home of the house of Pipin: their sovereign, although himself a Saxon by race, titled himself king of the Franks, in opposition to the Frankish rulers of the Western branch, whose Teutonic character was disappearing among the Romans of Gaul; they held themselves in every way the true representatives of the Carolingian power, and accounted the period since Arnulf’s death nothing but an interregnum which had suspended but not impaired their rights over Rome. ‘For so long,’ says a writer of the time, ‘as there remain kings of the Franks, so long will the dignity of the Roman Empire not wholly perish, seeing that it will abide in its kings.’ The recovery of Italy was therefore to German eyes a righteous as well as a glorious design: approved by the Teutonic Church which had lately been negotiating with Rome on the subject of missions to the heathen; embraced by the people, who saw in it an accession of strength to their young kingdom. Everything smiled on Otto’s enterprise, and the connection which was destined to bring so much strife and woe to Germany and to Italy was welcomed by the wisest of both countries as the beginning of a better era.

Descent of Otto the Great into Italy

Whatever were Otto’s own feelings, whether or not he felt that he was sacrificing, as modern writers have thought that he did sacrifice, the greatness of his German kingdom to the lust of universal dominion, he shewed no hesitation in his acts. Descending from the Alps with an overpowering force, he was acknowledged as king of Italy at Pavia; and, having first taken an oath to protect the Holy See and respect the liberties of the city, advanced to Rome.

His coronation at Rome, A.D. 962

There, with Adelheid his queen, he was crowned by John XII, on the day of the Purification, the second of February, A.D. 962. The details of his election and coronation are unfortunately still more scanty than in the case of his great predecessor. Most of our authorities represent the act as of the Pope’s favour, yet it is plain that the consent of the people was still thought an essential part of the ceremony, and that Otto rested after all on his host of conquering Saxons. Be this as it may, there was neither question raised nor opposition made in Rome; the usual courtesies and promises were exchanged between Emperor and Pope, the latter owning himself a subject, and the citizens swore for the future to elect no pontiff without Otto’s consent.