Editor’s Note: The following comprises the nineteenth chapter of The Holy Roman Empire, by James Bryce (published 1871). All spelling in the original.

(Continued from Part 18)

CHAPTER XIX

THE PEACE OF WESTPHALIA: LAST STAGE IN THE DECLINE OF THE EMPIRE

The Peace of Westphalia is the first, and, with the exception perhaps of the Treaties of Vienna in 1815, the most important of those attempts to reconstruct by diplomacy the European states-system which have played so large a part in modern history. It is important, however, not as marking the introduction of new principles, but as winding up the struggle which had convulsed Germany since the revolt of Luther, sealing its results, and closing definitively the period of the Reformation. Although the causes of disunion which the religious movement called into being had now been at work for more than a hundred years, their effects were not fully seen till it became necessary to establish a system which should represent the altered relations of the German states. It may thus be said of this famous peace, as of the other so-called ‘fundamental law of the Empire,’ the Golden Bull, that it did no more than legalize a condition of things already in existence, but which by being legalized acquired new importance. To all parties alike the result of the Thirty Years’ War was thoroughly unsatisfactory: to the Protestants, who had lost Bohemia, and still were obliged to hold an inferior place in the electoral college and in the Diet: to the Catholics, who were forced to permit the exercise of heretical worship, and leave the church lands in the grasp of sacrilegious spoilers: to the princes, who could not throw off the burden of imperial supremacy: to the Emperor, who could turn that supremacy to no practical account. No other conclusion was possible to a contest in which every one had been vanquished and no one victorious; which had ceased because while the reasons for war continued the means of war had failed. Nevertheless, the substantial advantage remained with the German princes, for they gained the formal recognition of that territorial independence whose origin may be placed as far back as the days of Frederick the Second, and the maturity of which had been hastened by the events of the last preceding century. It was, indeed, not only recognized but justified as rightful and necessary. For while the political situation, to use a current phrase, had changed within the last two hundred years, the eyes with which men regarded it had changed still more. Never by their fiercest enemies in earlier times, not once by the Popes or Lombard republicans in the heat of their strife with the Franconian and Swabian Cæsars, had the Emperors been reproached as mere German kings, or their claim to be the lawful heirs of Rome denied. The Protestant jurists of the sixteenth or rather of the seventeenth century were the first persons who ventured to scoff at the pretended lordship of the world, and declare their Empire to be nothing more than a German monarchy, in dealing with which no superstitious reverence need prevent its subjects from making the best terms they could for themselves, and controlling a sovereign whose religious predilections made him the friend of their enemies.

The treatise of Hippolytus a Lapide

It is very instructive to turn suddenly from Dante or Peter de Andlo to a book published shortly before A.D. 1648, under the name of Hippolytus a Lapide, and notice the matter-of-fact way, the almost contemptuous spirit in which, disregarding the traditional glories of the Empire, he comments on its actual condition and prospects. Hippolytus, the pseudonym which the jurist Chemnitz assumed, urges with violence almost superfluous, that the Germanic constitution must be treated entirely as a native growth: that the ‘lex regia’ (so much discussed and so often misunderstood) and the whole system of Justinianean absolutism which the Emperor had used so dexterously, were in their applications to Germany not merely incongruous but positively absurd. With eminent learning, Chemnitz examines the early history of the Empire, draws from the unceasing contests of the monarch with the nobility the unexpected moral that the power of the former has been always dangerous, and is now more dangerous than ever, and then launches out into a long invective against the policy of the Hapsburgs, an invective which the ambition and harshness of the late Emperor made only too plausible. The one real remedy for the evils that menace Germany he states concisely—‘domus Austriacæ extirpatio:’ but, failing this, he would have the Emperor’s prerogative restricted in every way, and provide means for resisting or dethroning him.

Rights of the Emperor and the Diet, as settled in A.D. 1648

It was by these views, which seem to have made a profound impression in Germany, that the states, or rather France and Sweden acting on their behalf, were guided in the negotiations of Osnabrück and Münster. By extorting a full recognition of the sovereignty of all the princes, Catholics and Protestants alike, in their respective territories, they bound the Emperor from any direct interference with the administration, either in particular districts or throughout the Empire. All affairs of public importance, including the rights of making war or peace, of levying contributions, raising troops, building fortresses, passing or interpreting laws, were henceforth to be left entirely in the hands of the Diet. The Aulic Council, which had been sometimes the engine of imperial oppression, and always of imperial intrigue, was so restricted as to be harmless for the future. The ‘reservata’ of the Emperor were confined to the rights of granting titles and confirming tolls. In matters of religion, an exact though not perfectly reciprocal equality was established between the two chief ecclesiastical bodies, and the right of ‘Itio in partes,’ that is to say, of deciding questions in which religion was involved by amicable negotiations between the Protestant and Catholic states, instead of by a majority of votes in the Diet, was definitely conceded. Both Lutherans and Calvinists were declared free from all jurisdiction of the Pope or any Catholic prelate. Thus the last link which bound Germany to Rome was snapped, the last of the principles by virtue of which the Empire had existed was abandoned. For the Empire now contained and recognized as its members persons who formed a visible body at open war with the Holy Roman Church; and its constitution admitted schismatics to a full share in all those civil rights which, according to the doctrines of the early Middle Age, could be enjoyed by no one who was out of the communion of the Catholic Church. The Peace of Westphalia was therefore an abrogation of the sovereignty of Rome, and of the theory of Church and State with which the name of Rome was associated. And in this light was it regarded by Pope Innocent the Tenth, who commanded his legate to protest against it, and subsequently declared it void by the bull ‘Zelo domus Dei.’

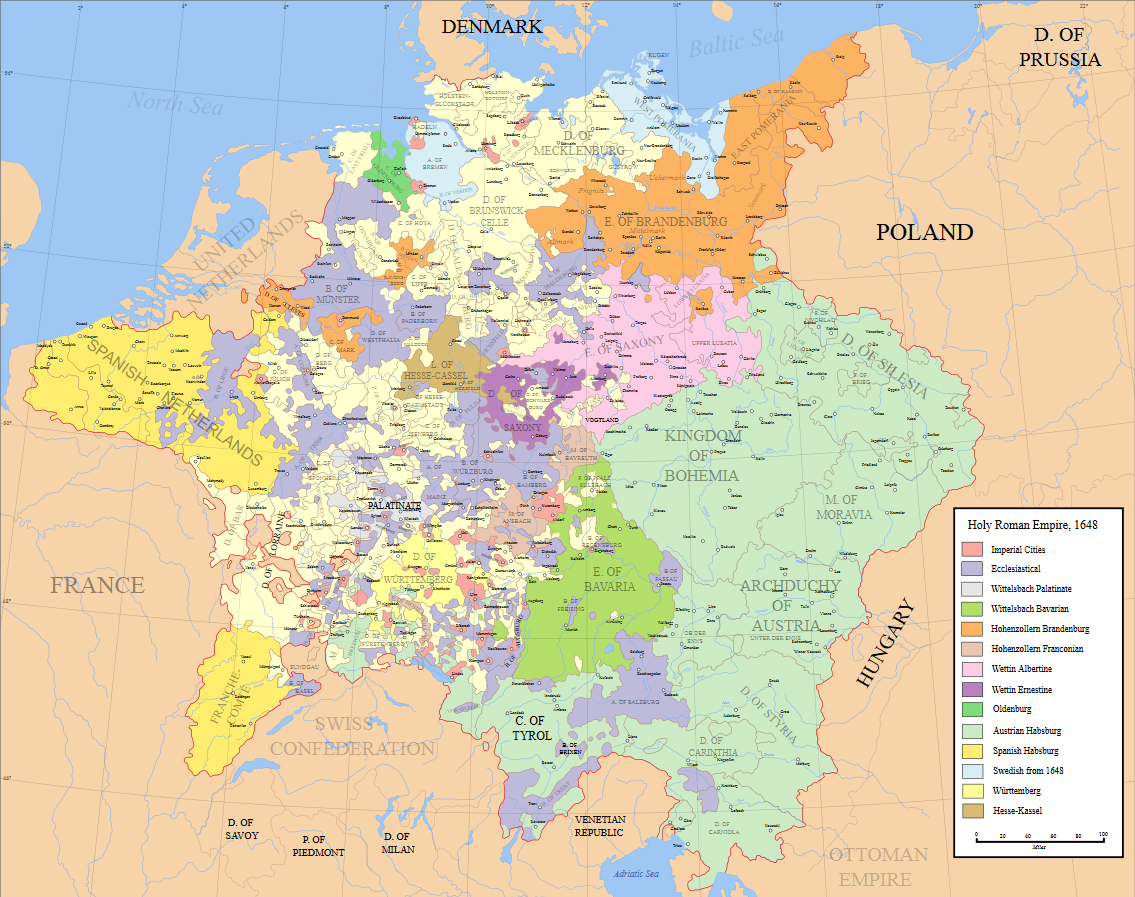

Loss of imperial territories

The transference of power within the Empire, from its head to its members, was a small matter compared with the losses which the Empire suffered as a whole. The real gainers by the treaties of Westphalia were those who had borne the brunt of the battle against Ferdinand the Second and his son. To France were ceded Brisac, the Austrian part of Alsace, and the lands of the three bishoprics in Lorraine—Metz, Toul, and Verdun, which her armies had seized in A.D. 1552: to Sweden, northern Pomerania, Bremen, and Verden. There was, however, this difference between the position of the two, that whereas Sweden became a member of the German Diet for what she received (as the king of Holland was, until 1866-7, a member for Dutch Luxemburg, and as the kings of Denmark, up till the accession of the present sovereign, were for Holstein), the acquisitions of France were delivered over to her in full sovereignty, and for ever severed from the Germanic body. And as it was by their aid that the liberties of the Protestants had been won, these two states obtained at the same time what was more valuable than territorial accessions—the right of interfering at imperial elections, and generally whenever the provisions of the treaties of Osnabrück and Münster, which they had guaranteed, might be supposed to be endangered. The bounds of the Empire were further narrowed by the final separation of two countries, once integral parts of Germany, and up to this time legally members of her body. Holland and Switzerland were, in A.D. 1648, declared independent.

Germany after the Peace

The Peace of Westphalia is an era in imperial history not less clearly marked than the coronation of Otto the Great, or the death of Frederick the Second. As from the days of Maximilian it had borne a mixed or transitional character, well expressed by the name Romano-Germanic, so henceforth it is in everything but title purely and solely a German Empire. Properly, indeed, it was no longer an Empire at all, but a Confederation, and that of the loosest sort. For it had no common treasury, no efficient common tribunals, no means of coercing a refractory member; its states were of different religions, were governed according to different forms, were administered judicially and financially without any regard to each other.

Number of petty independent states: effects of such a system on Germany

The traveller in Central Germany now is amused to find, every hour or two, by the change in the soldiers’ uniforms, and the colour of the stripes on the railway fences, that he has passed out of one and into another of its miniature kingdoms. Much more surprised and embarrassed would he have been a century ago, when, instead of the present thirty-two there were three hundred petty principalities between the Alps and the Baltic, each with its own laws, its own courts (in which the ceremonious pomp of Versailles was faintly reproduced), its little armies, its separate coinage, its tolls and custom-houses on the frontier, its crowd of meddlesome and pedantic officials, presided over by a prime minister who was generally the unworthy favourite of his prince and the pensioner of some foreign court. This vicious system, which paralyzed the trade, the literature, and the political thought of Germany, had been forming itself for some time, but did not become fully established until the Peace of Westphalia, by emancipating the princes from imperial control, had made them despots in their own territories. The impoverishment of the inferior nobility and the decline of the commercial cities caused by a war that had lasted a whole generation, removed every counterpoise to the power of the electors and princes, and made absolutism supreme just where absolutism wants all its justification, in states too small to have any public opinion, states in which everything depends on the monarch, and the monarch depends on his favourites. After A.D. 1648 the provincial estates or parliaments became obsolete in most of these principalities, and powerless in the rest. Germany was forced to drink to its very dregs the cup of feudalism, feudalism from which all the feelings that once ennobled it had departed.

Feudalism in France, England, Germany

It is instructive to compare the results of the system of feudality in the three chief countries of modern Europe. In France, the feudal head absorbed all the powers of the state, and left to the aristocracy only a few privileges, odious indeed, but politically worthless. In England, the mediæval system expanded into a constitutional monarchy, where the oligarchy was still strong, but the commons had won the full recognition of equal civil rights. In Germany, everything was taken from the sovereign, and nothing given to the people; the representatives of those who had been fief-holders of the first and second rank before the Great Interregnum were now independent potentates; and what had been once a monarchy was now an aristocratic federation. The Diet, originally an assembly of magnates meeting from time to time like our early English Parliaments, became in A.D. 1654 a permanent body, at which the electors, princes, and cities were represented by their envoys. In other words, it was now not a national council, but an international congress of diplomatists.

Causes of the continuance of the Empire

Where the sacrifice of imperial, or rather federal, rights to state rights was so complete, we may wonder that the farce of an Empire should have been retained at all. A mere German Empire would probably have perished; but the Teutonic people could not bring itself to abandon the venerable heritage of Rome. Moreover, the Germans were of all European peoples the most slow-moving and long-suffering; and as, if the Empire had fallen, something must have been erected in its place, they preferred to work on with the clumsy machine so long as it would work at all. Properly speaking, it has no history after this; and the history of the particular states of Germany which takes its place is one of the dreariest chapters in the annals of mankind. It would be hard to find, from the Peace of Westphalia to the French Revolution, a single grand character or a single noble enterprise; a single sacrifice made to great public interests, a single instance in which the welfare of nations was preferred to the selfish passions of their princes. The military history of those times will always be read with interest; but free and progressive countries have a history of peace not less rich and varied than that of war; and when we ask for an account of the political life of Germany in the eighteenth century, we hear nothing but the scandals of buzzing courts, and the wrangling of diplomatists at never-ending congresses.

The Empire and the Balance of power

Useless and helpless as the Empire had become, it was not without its importance to the neighbouring countries, with whose fortunes it had been linked by the Peace of Westphalia. It was the pivot on which the political system of Europe was to revolve: the scales, so to speak, which marked the equipoise of power that had become the grand object of the policy of all states. This modern caricature of the plan by which the theorists of the fourteenth century had proposed to keep the world at peace, used means less noble and attained its end no better than theirs had done. No one will deny that it was and is desirable to prevent a universal monarchy in Europe. But it may be asked whether a system can be considered successful which allowed Frederick of Prussia to seize Silesia, which did not check the aggressions of Russia and France upon their neighbours, which was for ever bartering and exchanging lands in every part of Europe without thought of the inhabitants, which permitted and has never been able to redress that greatest of public misfortunes, the partitionment of Poland. And if it be said that bad as things have been under this system, they would have been worse without it, it is hard to refrain from asking whether any evils could have been greater than those which the people of Europe have suffered through constant wars with each other, and through the withdrawal, even in time of peace, of so large a part of their population from useful labour to be wasted in maintaining a standing army.

Position of the Empire in Europe

The result of the extended relations in which Germany now found herself to Europe, with two foreign kings never wanting an occasion, one of them never the wish, to interfere, was that a spark from her set the Continent ablaze, while flames kindled elsewhere were sure to spread hither. Matters grew worse as her princes inherited or created so many thrones abroad. The Duke of Holstein acquired Denmark, the Count Palatine Sweden, the Elector of Saxony Poland, the Elector of Hanover England, the Archduke of Austria Hungary and Bohemia, while the Elector (originally Margrave) of Brandenburg obtained, on the strength of non-imperial territories to the north-eastward which had come into his hands, the style and title of King of Prussia. Thus the Empire seemed again about to embrace Europe; but in a sense far different from that which those words would have expressed under Charles and Otto. Its history for a century and a half is a dismal list of losses and disgraces. The chief external danger was from French influence, for a time supreme, always menacing. For though Lewis the Fourteenth, on whom, in A.D. 1658, half the electoral college wished to confer the imperial crown, was before the end of his life an object of intense hatred, officially entitled ‘Hereditary enemy of the Holy Empire,’ France had nevertheless a strong party among the princes always at her beck. The Rhenish and Bavarian electors were her favourite tools. The ‘réunions‘ begun in A.D. 1680, a pleasant euphemism for robbery in time of peace, added Strasburg and other places in Alsace, Lorraine, and Franche Comté to the monarchy of Lewis, and brought him nearer the heart of the Empire; his ambition and cruelty were witnessed to by repeated wars, and by the devastation of the Rhine countries; the ultimate though short-lived triumph of his policy was attained when Marshal Belleisle dictated the election of Charles VII in A.D. 1742. In the Turkish wars, when the princes left Vienna to be saved by the Polish Sobieski, the Empire’s weakness appeared in a still more pitiable light.

Weakness and stagnation of Germany

There was, indeed, a complete loss of hope and interest in the old system. The princes had been so long accustomed to consider themselves the natural foes of a central government, that a request made by it was sure to be disregarded; they aped in their petty courts the pomp and etiquette of Vienna or Paris, grumbling that they should be required to garrison the great frontier fortresses which alone protected them from an encroaching neighbour. The Free Cities had never recovered the famines and sieges of the Thirty Years’ War: Hanseatic greatness had waned, and the southern towns had sunk into languid oligarchies. All the vigour of the people in a somewhat stagnant age either found its sphere in rising states like the Prussia of Frederick the Great, or turned away from politics altogether into other channels. The Diet had become contemptible from the slowness with which it moved, and its tedious squabbles on matters the most frivolous. Many sittings were consumed in the discussion of a question regarding the time of keeping Easter, more ridiculous than that which had distracted the Western churches in the seventh century, the Protestants refusing to reckon by the reformed calendar because it was the work of a Pope. Collective action through the old organs was confessed impossible, when the common object of defence against France was sought by forming a league under the Emperor’s presidency, and when at European congresses the Empire was not represented at all. No change could come from the Emperor, whom the capitulation of A.D. 1658 deposed ipso facto if he violated its provisions. As Dohm said, to keep him from doing harm, he was kept from doing anything.

Leopold I, 1658-1705, Joseph I, 1705-1711, Charles VI, 1711-1742

Yet little was lost by his inactivity, for what could have been hoped from his action? From the election of Albert the Second, A.D. 1437, to the death of Charles the Sixth, A.D. 1742, the sceptre had remained in the hands of one family. So far from being fit subjects for undistinguishing invective, the Hapsburg Emperors may be contrasted favourably with the contemporary dynasties of France, Spain, or England. Their policy, viewed as a whole from the days of Rudolf downwards, had been neither conspicuously tyrannical, nor faltering, nor dishonest. But it had been always selfish. Entrusted with an office which might, if there be any power in those memories of the past to which the champions of hereditary monarchy so constantly appeal, have stirred their sluggish souls with some enthusiasm for the heroes on whose throne they sat, some wish to advance the glory and the happiness of Germany, they had cared for nothing, sought nothing, used the Empire as an instrument for nothing but the attainment of their own personal or dynastic ends.

The Hapsburg Emperors and their policy

Placed on the eastern verge of Germany, the Hapsburgs had added to their ancient lands in Austria proper and Tyrol, non-German territories far more extensive, and had thus become the chiefs of a separate and independent state. They endeavoured to reconcile its interests with the interests of the Empire, so long as it seemed possible to recover part of the old imperial prerogative. But when such hopes were dashed by the defeats of the Thirty Years’ War, they hesitated no longer between an elective crown and the rule of their hereditary states, and comported themselves thenceforth in European politics not as the representatives of Germany, but as heads of the great Austrian monarchy. There would have been nothing culpable in this had they not at the same time continued to entangle Germany in wars with which she had no concern: to waste her strength in tedious combats with the Turks, or plunge her into a new struggle with France, not to defend her frontiers or recover the lands she had lost, but that some scion of the house of Hapsburg might reign in Spain or Italy. Watching the whole course of their foreign policy, marking how in A.D. 1736 they had bartered away Lorraine for Tuscany, a German for a non-German territory, and seeing how at home they opposed every scheme of reform which could in the least degree trench upon their own prerogative, how they strove to obstruct the imperial chamber lest it should interfere with their own Aulic council, men were driven to separate the body of the Empire from the imperial office and its possessors, and when plans for reinvigorating the one failed, to leave the others to their fate.

Causes of the long retention of the throne by Austria

Still the old line clung to the crown with that Hapsburg gripe which has almost passed into a proverb. Odious as Austria was, no one could despise her, or fancy it easy to shake her commanding position in Europe. Her alliances were fortunate: her designs were steadily pursued: her dismembered territories always returned to her. Though the throne continued strictly elective, it was impossible not to be influenced by long prescription. Projects were repeatedly formed to set the Hapsburgs aside by electing a prince of some other line, or by passing a law that there should never be more than two, or four, successive Emperors of the same house. France ever and anon renewed her warnings to the electors, that their freedom was passing from them, and the sceptre becoming hereditary in one haughty family. But it was felt that a change would be difficult and disagreeable, and that the heavy expense and scanty revenues of the Empire required to be supported by larger patrimonial domains than most German princes possessed. The heads of states like Prussia and Hanover, states whose size and wealth would have made them suitable candidates, were Protestants, and so excluded both by the connexion of the imperial office with the Church, and by the majority of Roman Catholics in the electoral college, who, however jealous they might be of Austria, were led both by habit and sympathy to rally round her in moments of peril. The one occasion on which these considerations were disregarded shewed their force.

Charles VII, 1742-1745

On the extinction of the male line of Hapsburg in the person of Charles the Sixth, the intrigues of the French envoy, Marshal Belleisle, procured the election of Charles Albert of Bavaria, who stood first among the Catholic princes. His reign was a succession of misfortunes and ignominies. Driven from Munich by the Austrians, the head of the Holy Empire lived in Frankfort on the bounty of France, cursed by the country on which his ambition had brought the miseries of a protracted war.

Francis I, 1745-1765

The choice in 1745 of Duke Francis of Lorraine, husband of the archduchess of Austria and queen of Hungary, Maria Theresa, was meant to restore the crown to the only power capable of wearing it with dignity: in Joseph the Second, her son, it again rested on the brow of a Hapsburg.

Seven Years’ War

In the war of the Austrian succession, which followed on the death of Charles the Sixth, the Empire as a body took no part; in the Seven Years’ War its whole might broke in vain against one resolute member. Under Frederick the Great Prussia approved herself at least a match for France and Austria leagued against her, and the semblance of unity which the predominance of a single power had hitherto given to the Empire was replaced by the avowed rivalry of two military monarchies.

Joseph II, 1765-1790

The Emperor Joseph the Second, a sort of philosopher-king, than whom few have more narrowly missed greatness, made a desperate effort to set things right, striving to restore the disordered finances, to purge and vivify the Imperial Chamber. Nay, he renounced the intolerant policy of his ancestors, quarrelled with the Pope, and presumed to visit Rome, whose streets heard once more the shout that had been silent for three centuries, ‘Evviva il nostro imperatore! Siete a casa vostra: siete il padrone.’ But his indiscreet haste was met by a sullen resistance, and he died disappointed in plans for which the time was not yet ripe, leaving no result save the league of princes which Frederick the Great had formed to oppose his designs on Bavaria.

Leopold II, 1790-1792. Last phase of the Empire

His successor, Leopold the Second, abandoned the projected reforms, and a calm, the calm before the hurricane, settled down again upon Germany. The existence of the Empire was almost forgotten by its subjects: there was nothing to remind them of it but a feudal investiture now and then at Vienna (real feudal rights were obsolete); a concourse of solemn old lawyers at Wetzlar puzzling over interminable suits; and some thirty diplomatists at Regensburg, the relics of that Imperial Diet where once a hero-king, a Frederick or a Henry, enthroned amid mitred prelates and steel-clad barons, had issued laws for every tribe from the Mediterranean to the Baltic.

The Diet

The solemn triflings of this so-called ‘Diet of Deputation’ have probably never been equalled elsewhere. Questions of precedence and title, questions whether the envoys of princes should have chairs of red cloth like those of the electors, or only of the less honourable green, whether they should be served on gold or on silver, how many hawthorn boughs should be hung up before the door of each on May-day; these, and such as these, it was their chief employment not to settle but to discuss. The pedantic formalism of old Germany passed that of Spaniards or Turks; it had now crushed under a mountain of rubbish whatever meaning or force its old institutions had contained. It is the penalty of greatness that its form should outlive its substance: that gilding and trappings should remain when that which they were meant to deck and clothe has departed. So our sloth or our timidity, not seeing that whatever is false must be also bad, maintains in being what once was good long after it has become helpless and hopeless: so now at the close of the eighteenth century, strings of sounding titles were all that was left of the Empire which Charles had founded, and Frederick adorned, and Dante sung.

Feelings of the German people

The German mind, just beginning to put forth the blossoms of its wondrous literature, turned away in disgust from the spectacle of ceremonious imbecility more than Byzantine. National feeling seemed gone from princes and people alike. Lessing, who did more than any one else to create the German literary spirit, says, ‘Of the love of country I have no conception: it appears to me at best a heroic weakness which I am right glad to be without.’ The Emperor Joseph II writes to his brother of France: ‘You must know that the annihilation of German nationality is a necessary leading principle of my policy.’ There were nevertheless persons who saw how fatal such a system was, lying like a nightmare on the people’s soul. Speaking of the union of princes formed by Frederick of Prussia to preserve the existing condition of things, Johannes von Müller writes: ‘If the German Union serves for nothing better than to maintain the status quo, it is against the eternal order of God, by which neither the physical nor the moral world remains for a moment in the status quo, but all is life and motion and progress. To exist without law or justice, without security from arbitrary imposts, doubtful whether we can preserve from day to day our honours, our liberties, our rights, our lives, helpless before superior force, without a beneficial connexion between our states, without a national spirit at all, this is the status quo of our nation. And it was this that the Union was meant to confirm. If it be this and nothing more, then bethink you how when Israel saw that Rehoboam would not hearken, the people gave answer to the king and spake, “What portion have we in David, or what inheritance in the son of Jesse? to your tents, O Israel: David, see to thine own house.” See then to your own houses, ye princes.’

Nevertheless, though the Empire stood like a corpse brought forth from some Egyptian sepulchre, ready to crumble at a touch, there seemed no reason why it should not stand so for centuries more. Fate was kind, and slew it in the light.