Editor’s Note: The following comprises the eighteenth chapter of The Holy Roman Empire, by James Bryce (published 1871). All spelling in the original.

(Continued from Part 17)

CHAPTER XVIII

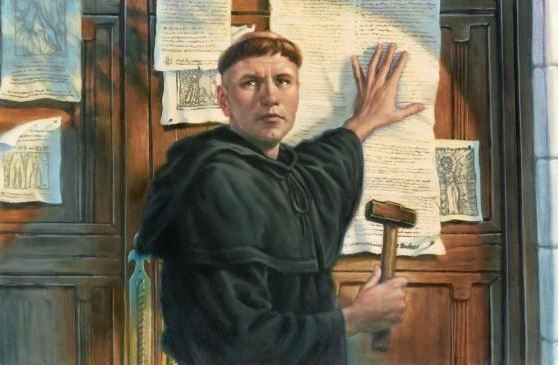

THE REFORMATION AND ITS EFFECTS UPON THE EMPIRE

The Reformation falls to be mentioned here, of course not as a religious movement, but as the cause of political changes, which still further rent the Empire, and struck at the root of the theory by which it had been created and upheld. Luther completed the work of Hildebrand. Hitherto it had seemed not impossible to strengthen the German state into a monarchy, compact if not despotic; the very Diet of Worms, where the monk of Wittenberg proclaimed to an astonished church and Emperor that the day of spiritual tyranny was past, had framed and presented a fresh scheme for the construction of a central council of government. The great religious schism put an end to all such hopes, for it became a source of political disunion far more serious and permanent than any that had existed before, and it taught the two factions into which Germany was henceforth divided to regard each other with feelings more bitter than those of hostile nations.

Accession of Charles V (1519-1558)

The breach came at the most unfortunate time possible. After an election, more memorable than any preceding, an election in which Francis the First of France and Henry the Eighth of England had been his competitors, a prince had just ascended the imperial throne who united dominions vaster than any Europe had seen since the days of his great namesake. Spain and Naples, Flanders, and other parts of the Burgundian lands, as well as large regions in Eastern Germany, obeyed Charles: he drew inexhaustible revenues from a new empire beyond the Atlantic. Such a power, directed by a mind more resolute and profound than that of Maximilian his grandfather, might have well been able, despite the stringency of his coronation engagements, and the watchfulness of the electors, to override their usurped privileges, and make himself practically as well as officially the head of the nation. Charles the Fifth, though from the coldness of his manner and his Flemish speech never a favourite among the Germans, was in point of fact far stronger than Maximilian or any other Emperor who had reigned for three centuries. In Italy he succeeded, after long struggles with the Pope and the French, in rendering himself supreme: England he knew how to lead, by flattering Henry and cajoling Wolsey: from no state but France had he serious opposition to fear. To this strength his imperial dignity was indeed a mere accident: its sources were the infantry of Spain, the looms of Flanders, the sierras of Peru. But the conquest once achieved, might could lose itself in right; and as an earlier Charles had veiled the terror of the Frankish sword under the mask of Roman election, so might his successor sway a hundred provinces with the sole name of Roman Emperor, and transmit to his race a dominion as wide and more enduring.

Attitude of Charles towards the religious movement

One is tempted to speculate as to what might have happened had Charles espoused the reforming cause. His reverence for the Pope’s person is sufficiently seen in the sack of Rome and the captivity of Clement; the traditions of his office might have led him to tread in the steps of the Henrys and the Fredericks, into which even the timid Lewis the Fourth and the unstable Sigismund had sometimes ventured; the awakening zeal of the German people, exasperated by the exactions of the Romish court, would have strengthened his hands, and enabled him, while moderating the excesses of change, to fix his throne on the deep foundations of national love. It may well be doubted—Englishmen at least have reason for the doubt—whether the Reformation would not have lost as much as it could have gained by being entangled in the meshes of royal patronage. But, setting aside Charles’s personal leaning to the old faith, and forgetting that he was king of the most bigoted race of Europe, his position as Emperor made him almost perforce the Pope’s ally. The Empire had been called into being by Rome, had vaunted the protection of the Apostolic See as its highest earthly privilege, had latterly been wont, especially in Hapsburg hands, to lean on the papacy for support. Itself founded entirely on prescription and the traditions of immemorial reverence, how could it abandon the cause which the longest prescription and the most solemn authority had combined to consecrate? With the German clergy, despite occasional quarrels, it had been on better terms than with the lay aristocracy; their heads had been the chief ministers of the crown; the advocacies of their abbeys were the last source of imperial revenue to disappear. To turn against them now, when furiously assailed by heretics; to abrogate claims hallowed by antiquity and a hundred laws, would be to pronounce its own sentence, and the fall of the eternal city’s spiritual dominion must involve the fall of what still professed to be her temporal. Charles would have been glad to see some abuses corrected; but a broad line of policy was called for, and he cast in his lot with the Catholics.

Ultimate failure of the repressive policy of Charles

Of many momentous results only a few need be noticed here. The reconstruction of the old imperial system, upon the basis of Hapsburg power, proved in the end impossible. Yet for some years it had seemed actually accomplished. When the Smalkaldic league had been dissolved and its leaders captured, the whole country lay prostrate before Charles. He overawed the Diet at Augsburg by the Spanish soldiery: he forced formularies of doctrine upon the vanquished Protestants: he set up and pulled down whom he would throughout Germany, amid the muttered discontent of his own partisans. Then, as in the beginning of the year 1552, he lay at Innsbruck, fondly dreaming that his work was done, waiting the spring weather to cross to Trent, where the Catholic fathers had again met to settle the world’s faith for it, news was suddenly brought that North Germany was in arms, and that the revolted Maurice of Saxony had seized Donauwerth, and was hurrying through the Bavarian Alps to surprise his sovereign. Charles rose and fled southwards over the snows of the Brenner, then eastwards, under the blood-red cliffs of dolomite that wall in the Pusterthal, far away into the valleys of Carinthia: the council of Trent broke up in consternation: Europe saw and the Emperor acknowledged that in his fancied triumph over the spirit of revolution he had done no more than block up for the moment an irresistible torrent. When this last effort to produce religious uniformity by violence had failed as hopelessly as the previous devices of holding discussions of doctrine and calling a general council, a sort of armistice was agreed to in 1554, which lasted in mutual fear and suspicion for more than sixty years.

Ferdinand I, 1558-1564

Four years after this disappointment of the hopes and projects which had occupied his busy life, Charles, weighed down by cares and with the shadow of coming death already upon him, resigned the sovereignty of Spain and the Indies, of Flanders and Naples, into the hands of his son Philip the Second; while the imperial sceptre passed to his brother Ferdinand, who had been some time before chosen King of the Romans.

Maximilian II, 1564-1576

Destruction of the Germanic state-system

Ferdinand was content to leave things much as he found them, and the amiable Maximilian II, who succeeded him, though personally well inclined to the Protestants, found himself fettered by his position and his allies, and could do little or nothing to quench the flame of religious and political hatred. Germany remained divided into two omnipresent factions, and so further than ever from harmonious action, or a tightening of the long-loosened bond of feudal allegiance. The states of either creed being gathered into a league, there could no longer be a recognized centre of authority for judicial or administrative purposes. Least of all could a centre be sought in the Emperor, the leader of the papal party, the suspected foe of every Protestant. Too closely watched to do anything of his own authority, too much committed to one party to be accepted as a mediator by the other, he was driven to attain his own objects by falling in with the schemes and furthering the selfish ends of his adherents, by becoming the accomplice or the tool of the Jesuits. The Lutheran princes addressed themselves to reduce a power of which they had still an over-sensitive dread, and found when they exacted from each successive sovereign engagements more stringent than his predecessor’s, that in this, and this alone, their Catholic brethren were not unwilling to join them. Thus obliged to strip himself one by one of the ancient privileges of his crown, the Emperor came to have little influence on the government except that which his intrigues might exercise. Nay, it became almost impossible to maintain a government at all. For when the Reformers found themselves outvoted at the Diet, they declared that in matters of religion a majority ought not to bind a minority. As the measures were few which did not admit of being reduced to this category, for whatever benefited the Emperor or any other Catholic prince injured the Protestants, nothing could be done save by the assent of two bitterly hostile factions. Thus scarce anything was done; and even the courts of justice were stopped by the disputes that attended the appointment of every judge or assessor.

Alliance of the Protestants with France

In the foreign politics of Germany another result followed. Inferior in military force and organization, the Protestant princes at first provided for their safety by forming leagues among themselves. The device was an old one, and had been employed by the monarch himself before now, in despair at the effete and cumbrous forms of the imperial system. Soon they began to look beyond the Vosges, and found that France, burning heretics at home, was only too happy to smile on free opinions elsewhere. The alliance was easily struck; Henry the Second assumed in 1552 the title of ‘Protector of the Germanic liberties,’ and a pretext for interference was never wanting in future.

The Reformation spirit, and its influence upon the Empire

These were some of the visible political consequences of the great religious schism of the sixteenth century. But beyond and above them there was a change far more momentous than any of its immediate results. There is perhaps no event in history which has been represented in so great a variety of lights as the Reformation. It has been called a revolt of the laity against the clergy, or of the Teutonic races against the Italians, or of the kingdoms of Europe against the universal monarchy of the Popes. Some have seen in it only a burst of long-repressed anger at the luxury of the prelates and the manifold abuses of the ecclesiastical system; others a renewal of the youth of the church by a return to primitive forms of doctrine. All these indeed to some extent it was; but it was also something more profound, and fraught with mightier consequences than any of them. It was in its essence the assertion of the principle of individuality—that is to say, of true spiritual freedom. Hitherto the personal consciousness had been a faint and broken reflection of the universal; obedience had been held the first of religious duties; truth had been conceived as a something external and positive, which the priesthood who were its stewards were to communicate to the passive layman, and whose saving virtue lay not in its being felt and known by him to be truth, but in a purely formal and unreasoning acceptance. The great principles which mediæval Christianity still cherished were obscured by the limited, rigid, almost sensuous forms which had been forced on them in times of ignorance and barbarism. That which was in its nature abstract, had been able to survive only by taking a concrete expression. The universal consciousness became the Visible Church: the Visible Church hardened into a government and degenerated into a hierarchy. Holiness of heart and life was sought by outward works, by penances and pilgrimages, by gifts to the poor and to the clergy, wherein there dwelt often little enough of a charitable mind. The presence of divine truth among men was symbolized under one aspect by the existence on earth of an infallible Vicar of God, the Pope; under another, by the reception of the present Deity in the sacrifice of the mass; in a third, by the doctrine that the priest’s power to remit sins and administer the sacraments depended upon a transmission of miraculous gifts which can hardly be called other than physical. All this system of doctrine, which might, but for the position of the church as a worldly and therefore obstructive power, have expanded, renewed, and purified itself during the four centuries that had elapsed since its completion, and thus remained in harmony with the growing intelligence of mankind, was suddenly rent in pieces by the convulsion of the Reformation, and flung away by the more religious and more progressive peoples of Europe. That which was external and concrete, was in all things to be superseded by that which was inward and spiritual. It was proclaimed that the individual spirit, while it continued to mirror itself in the world-spirit, had nevertheless an independent existence as a centre of self-issuing force, and was to be in all things active rather than passive. Truth was no longer to be truth to the soul until it should have been by the soul recognized, and in some measure even created; but when so recognized and felt, it is able under the form of faith to transcend outward works and to transform the dogmas of the understanding; it becomes the living principle within each man’s breast, infinite itself, and expressing itself infinitely through his thoughts and acts. He who as a spiritual being was delivered from the priest, and brought into direct relation with the Divinity, needed not, as heretofore, to be enrolled a member of a visible congregation of his fellows, that he might live a pure and useful life among them.

Effect of the Reformation on the doctrines regarding the Visible Church

Thus by the Reformation the Visible Church as well as the priesthood lost that paramount importance which had hitherto belonged to it, and sank from being the depositary of all religious tradition, the source and centre of religious life, the arbiter of eternal happiness or misery, into a mere association of Christian men, for the expression of mutual sympathy and the better attainment of certain common ends. Like those other doctrines which were now assailed by the Reformation, this mediæval view of the nature of the Visible Church had been naturally, and so, it may be said, necessarily developed between the third and the twelfth century, and must therefore have represented the thoughts and satisfied the wants of those times. By the Visible Church the flickering lamp of knowledge and literary culture, as well as of religion, had been fed and tended through the long night of the Dark Ages. But, like the whole theological fabric of which it formed a part, it was now hard and unfruitful, identified with its own worst abuses, capable apparently of no further development, and unable to satisfy minds which in growing stronger had grown more conscious of their strength. Before the awakened zeal of the northern nations it stood a cold and lifeless system, whose organization as a hierarchy checked the free activity of thought, whose bestowal of worldly power and wealth on spiritual pastors drew them away from their proper duties, and which by maintaining alongside of the civil magistracy a co-ordinate and rival government, maintained also that separation of the spiritual element in man from the secular, which had been so complete and so pernicious during the Middle Ages, which debases life, and severs religion from morality.

Consequent effect upon the Empire

The Reformation, it may be said, was a religious movement: and it is the Empire, not the Church, that we have here to consider. The distinction is only apparent. The Holy Empire is but another name for the Visible Church. It has been shewn already how mediæval theory constructed the State on the model of the Church; how the Roman Empire was the shadow of the Popedom—designed to rule men’s bodies as the pontiff ruled their souls. Both alike claimed obedience on the ground that Truth is One, and that where there is One faith there must be One government. And, therefore, since it was this very principle of Formal Unity that the Reformation overthrew, it became a revolt against despotism of every kind; it erected the standard of civil as well as of religious liberty, since both of them are needed, though needed in a different measure, for the worthy development of the individual spirit. The Empire had never been conspicuously the antagonist of popular freedom, and was, even under Charles the Fifth, far less formidable to the commonalty than were the petty princes of Germany. But submission, and submission on the ground of indefeasible transmitted right, upon the ground of Catholic traditions and the duty of the Christian magistrate to suffer heresy and schism as little as the parallel sins of treason and rebellion, had been its constant claim and watchword. Since the days of Julius Cæsar it had passed through many phases, but in none of them had it ever been a constitutional monarchy, pledged to the recognition of popular rights. And hence the indirect tendency of the Reformation to narrow the province of government and exalt the privileges of the subject was as plainly adverse to the Empire as the Protestant claim of the right of private judgment was to the pretensions of the Papacy and the priesthood.

Immediate influence of the Reformation on political and religious liberty

The remark must not be omitted in passing, how much less than might have been expected the religious movement did at first actually effect in the way of promoting either political progress or freedom of conscience. The habits of centuries were not to be unlearnt in a few years, and it was natural that ideas struggling into existence and activity should work erringly and imperfectly for a time. By a few inflammable minds liberty was carried into antinomianism, and produced the wildest excesses of life and doctrine. Several fantastic sects arose, refusing to conform to the ordinary rules without which human society could not subsist. But these commotions neither spread widely nor lasted long.

Conduct of the Protestant States

Far more pervading and more remarkable was the other error, if that can be called an error which was the almost unavoidable result of the circumstances of the time. The principles which had led the Protestants to sever themselves from the Roman Church, should have taught them to bear with the opinions of others, and warned them from the attempt to connect agreement in doctrine or manner of worship with the necessary forms of civil government. Still less ought they to have enforced that agreement by civil penalties; for faith, upon their own shewing, had no value save when it was freely given. A church which does not claim to be infallible is bound to allow that some part of the truth may possibly be with its adversaries: a church which permits or encourages human reason to apply itself to revelation has no right first to argue with people and then to punish them if they are not convinced. But whether it was that men only half saw what they had done, or that finding it hard enough to unrivet priestly fetters, they welcomed all the aid a temporal prince could give, the result was that religion, or rather religious creeds, began to be involved with politics more closely than had ever been the case before. Through the greater part of Christendom wars of religion raged for a century or more, and down to our own days feelings of theological antipathy continue to affect the relations of the powers of Europe. In almost every country the form of doctrine which triumphed associated itself with the state, and maintained the despotic system of the Middle Ages, while it forsook the grounds on which that system had been based. It was thus that there arose National Churches, which were to be to the several countries of Europe that which the Church Catholic had been to the world at large; churches, that is to say, each of which was to be co-extensive with its respective state, was to enjoy landed wealth and exclusive political privilege, and was to be armed with coercive powers against recusants. It was not altogether easy to find a set of theoretical principles on which such churches might be made to rest, for they could not, like the old church, point to the historical transmission of their doctrines; they could not claim to have in any one man or body of men an infallible organ of divine truth; they could not even fall back upon general councils, or the argument, whatever it may be worth, ‘Securus iudicat orbis terrarum.’ But in practice these difficulties were soon got over, for the dominant party in each state, if it was not infallible, was at any rate quite sure that it was right, and could attribute the resistance of other sects to nothing but moral obliquity. The will of the sovereign, as in England, or the will of the majority, as in Holland, Scandinavia, and Scotland, imposed upon each country a peculiar form of worship, and kept up the practices of mediæval intolerance without their justification. Persecution, which might be at least excused in an infallible Catholic and Apostolic Church, was peculiarly odious when practised by those who were not catholic, who were no more apostolic than their neighbours, and who had just revolted from the most ancient and venerable authority in the name of rights which they now denied to others. If union with the visible church by participation in a material sacrament be necessary to eternal life, persecution may be held a duty, a kindness to perishing souls. But if the kingdom of heaven be in every sense a kingdom of the spirit, if saving faith be possible out of one visible body and under a diversity of external forms, persecution becomes at once a crime and a folly. Therefore the intolerance of Protestants, if the forms it took were less cruel than those practised by the Roman Catholics, was also far less defensible; for it had seldom anything better to allege on its behalf than motives of political expediency, or, more often, the mere headstrong passion of a ruler or a faction to silence the expressions of any opinions but their own. To enlarge upon this theme, did space permit it, would not be to digress from the proper subject of this narrative. For the Empire, as has been said more than once already, was far less an institution than a theory or doctrine. And hence it is not too much to say, that the ideas which have but recently ceased to prevail regarding the duty of the magistrate to compel uniformity in doctrine and worship by the civil arm, may all be traced to the relation which that doctrine established between the Roman Church and the Roman Empire; to the conception, in fact, of an Empire Church itself.

Influence of the Reformation on the name and associations of the Empire

Two of the ways in which the Reformation affected the Empire have been now described: its immediate political results, and its far more profound doctrinal importance, as implanting new ideas regarding the nature of freedom and the province of government. A third, though apparently almost superficial, cannot be omitted. Its name and its traditions, little as they retained of their former magic power, were still such as to excite the antipathy of the German reformers. The form which the doctrine of the supreme importance of one faith and one body of the faithful had taken was the dominion of the ancient capital of the world through her spiritual head, the Roman bishop, and her temporal head, the Emperor. As the names of Roman and Christian had been once convertible, so long afterwards were those of Roman and Catholic. The Reformation, separating into its parts what had hitherto been one conception, attacked Romanism but not Catholicity, and formed religious communities which, while continuing to call themselves Christian, repudiated the form with which Christianity had been so long identified in the West. As the Empire was founded upon the assumption that the limits of Church and State are exactly co-extensive, a change which withdrew half of its subjects from the one body while they remained members of the other, transformed it utterly, destroyed the meaning and value of its old arrangements, and forced the Emperor into a strange and incongruous position. To his Protestant subjects he was merely the head of the administration, to the Catholics he was also the Defender and Advocate of their church. Thus from being chief of the whole state he became the chief of a party within it, the Corpus Catholicorum, as opposed to the Corpus Evangelicorum; he lost what had been hitherto his most holy claim to the obedience of the subject; the awakened feeling of German nationality was driven into hostility to an institution whose title and history bound it to the centre of foreign tyranny. After exulting for seven centuries in the heritage of Roman rule, the Teutonic nations cherished again the feelings with which their ancestors had resisted Julius Cæsar and Germanicus. Two mutually repugnant systems could not exist side by side without striving to destroy one another. The instincts of theological sympathy overcame the duties of political allegiance, and men who were subjects both of the Empire and of their local prince, gave all their loyalty to him who espoused their doctrines and protected their worship. For in North Germany, princes as well as people were mostly Lutheran: in the southern and especially the south-eastern lands, where the magnates held to the old faith, Protestants were scarcely to be found except in the free cities. The same causes which injured the Emperor’s position in Germany swept away the last semblance of his authority through other countries. In the great struggle which followed, the Protestants of England and France, of Holland and Sweden, thought of him only as the ally of Spain, of the Vatican, of the Jesuits; and he of whom it had been believed a century before that by nothing but his existence was the coming of Antichrist on earth delayed, was in the eyes of the northern divines either Antichrist himself or Antichrist’s foremost champion. The earthquake that opened a chasm in Germany was felt through Europe; its states and peoples marshalled themselves under two hostile banners, and with the Empire’s expiring power vanished that united Christendom it had been created to lead.

Troubles of Germany

Rudolf II, 1576-1612, Matthias, 1612-1619

Some of the effects thus sketched began to shew themselves as early as that famous Diet of Worms, from Luther’s appearance at which, in A.D. 1521, we may date the beginning of the Reformation. But just as the end of the religious conflict in England can hardly be placed earlier than the Revolution of 1688, nor in France than the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, so it was not till after more than a century of doubtful strife that the new order of things was fully and finally established in Germany. The arrangements of Augsburg, like most treaties on the basis of uti possidetis, were no better than a hollow truce, satisfying no one, and consciously made to be broken. The church lands which Protestants had seized, and Jesuit confessors urged the Catholic princes to reclaim, furnished an unceasing ground of quarrel: neither party yet knew the strength of its antagonists sufficiently to abstain from insulting or persecuting their modes of worship, and the smouldering hate of half a century was kindled by the troubles of Bohemia into the Thirty Years’ War.

Thirty Years’ War, 1618-1648

Ferdinand II, A.D. 1619-37

The imperial sceptre had now passed from the indolent and vacillating Rudolf II (1576-1612), the corrupt and reckless policy of whose ministers had done much to exasperate the already suspicious minds of the Protestants, into the firmer grasp of Ferdinand the Second. Jealous, bigoted, implacable, skilful in forming and concealing his plans, resolute to obstinacy in carrying them out in action, the house of Hapsburg could have had no abler and no more unpopular leader in their second attempt to turn the German Empire into an Austrian military monarchy. They seemed for a time as near to the accomplishment of the project as Charles the Fifth had been.

Plans of Ferdinand II

Leagued with Spain, backed by the Catholics of Germany, served by such a leader as Wallenstein, Ferdinand proposed nothing less than the extension of the Empire to its old limits, and the recovery of his crown’s full prerogative over all its vassals. Denmark and Holland were to be attacked by sea and land: Italy to be reconquered with the help of Spain: Maximilian of Bavaria and Wallenstein to be rewarded with principalities in Pomerania and Mecklenburg. The latter general was all but master of Northern Germany when the successful resistance of Stralsund turned the wavering balance of the war.

Gustavus Adolphus

Soon after (A.D. 1630), Gustavus Adolphus crossed the Baltic, and saved Europe from an impending reign of the Jesuits. Ferdinand’s high-handed proceedings had already alarmed even the Catholic princes. Of his own authority he had put the Elector Palatine and other magnates to the ban of the Empire: he had transferred an electoral vote to Bavaria; had treated the districts overrun by his generals as spoil of war, to be portioned out at his pleasure; had unsettled all possession by requiring the restitution of church property occupied since A.D. 1555. The Protestants were helpless; the Catholics, though they complained of the flagrant illegality of such conduct, did not dare to oppose it: the rescue of Germany was the work of the Swedish king. In four campaigns he destroyed the armies and the prestige of the Emperor; devastated his lands, emptied his treasury, and left him at last so enfeebled that no subsequent successes could make him again formidable.

Ferdinand III, 1637-1658

The peace of Westphalia

Such, nevertheless, was the selfishness and apathy of the Protestant princes, divided by the mutual jealousy of the Lutheran and the Calvinist party—some, like the Saxon elector, most inglorious of his inglorious house, bribed by the cunning Austrian; others afraid to stir lest a reverse should expose them unprotected to his vengeance—that the issue of the long protracted contest would have gone against them but for the interference of France. It was the leading principle of Richelieu’s policy to depress the house of Hapsburg and keep Germany disunited: hence he fostered Protestantism abroad while trampling it down at home. The triumph he did not live to see was sealed in A.D. 1648, on the utter exhaustion of all the combatants, and the treaties of Münster and Osnabrück were thenceforward the basis of the Germanic constitution.