Editor’s Note: The following comprises the fourteenth chapter of The Holy Roman Empire, by James Bryce (published 1871). All spelling in the original.

(Continued from Part 13)

CHAPTER XIV

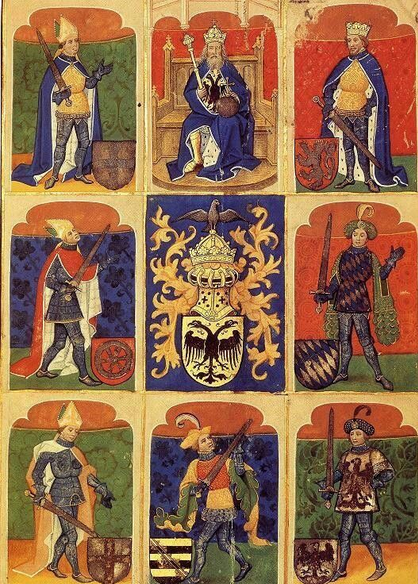

THE GERMANIC CONSTITUTION: THE SEVEN ELECTORS

Territorial Sovereignty of the Princes

Adolf, 1292-1298, Albert I, 1298-1308, Henry VII, 1308-1314, Lewis IV, 1314-1347

The reign of Frederick the Second was not less fatal to the domestic power of the German king than to the European supremacy of the Emperor. His two Pragmatic Sanctions had conferred rights that made the feudal aristocracy almost independent, and the long anarchy of the Interregnum had enabled them not only to use but to extend and fortify their power. Rudolf of Hapsburg had striven, not wholly in vain, to coerce their insolence, but the contest between his son Albert and Adolf of Nassau which followed his death, the short and troubled reign of Albert himself, the absence of Henry the Seventh in Italy, the civil war of Lewis of Bavaria and Frederick duke of Austria, rival claimants of the imperial throne, the difficulties in which Lewis, the successful competitor, found himself involved with the Pope—all these circumstances tended more and more to narrow the influence of the crown and complete the emancipation of the turbulent nobles. They now became virtually supreme in their own domains, enjoying full jurisdiction, certain appeals excepted, the right of legislation, privileges of coining money, of levying tolls and taxes: some were without even a feudal bond to remind them of their allegiance. The numbers of the immediate nobility—those who held directly of the crown—had increased prodigiously by the extinction of the dukedoms of Saxony, Franconia, and Swabia: along the Rhine the lord of a single tower was usually a sovereign prince. The petty tyrants whose boast it was that they owed fealty only to God and the Emperor, shewed themselves in practice equally regardless of both powers. Pre-eminent were the three great houses of Austria, Bavaria, and Luxemburg, this last having acquired Bohemia, A.D. 1309; next came the electors, already considered collectively more important than the Emperor, and forming for themselves the first considerable principalities. Brandenburg and the Rhenish Palatinate are strong independent states before the end of this period: Bohemia and the three archbishoprics almost from its beginning. The chief object of the magnates was to keep the monarch in his present state of helplessness. Till the expenses which the crown entailed were found ruinous to its wearer, their practice was to confer it on some petty prince, such as were Rudolf and Adolf of Nassau and Gunther of Schwartzburg, seeking when they could to keep it from settling in one family. They bound the newly-elected to respect all their present immunities, including those which they had just extorted as the price of their votes; they checked all his attempts to recover lost lands or rights: they ventured at last to depose their anointed head, Wenzel of Bohemia.

Policy of the Emperors

Thus fettered, the Emperor sought only to make the most of his short tenure, using his position to aggrandize his family and raise money by the sale of crown estates and privileges. His individual action and personal relation to the subject was replaced by a merely legal and formal one: he represented order and legitimate ownership, and so far was still necessary to the political system. But progresses through the country were abandoned: unlike his predecessors, who had resigned their patrimony when they assumed the sceptre, he lived mostly in his own states, often without the Empire’s bounds. Frederick III never entered it for twenty-seven years. How thoroughly the national character of the office was gone is shewn by the repeated attempts to bestow it on foreign potentates, who could not fill the place of a German king of the good old vigorous type. Not to speak of Richard and Alfonso, Charles of Valois was proposed against Henry VII, Edward III of England actually elected against Charles IV (his parliament forbade him to accept), George Podiebrad, king of Bohemia, against Frederick III. Sigismund was virtually a Hungarian king.

Power of the cities

The Emperor’s only hope would have been in the support of the cities. During the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries they had increased wonderfully in population, wealth, and boldness: the Hanseatic confederacy was the mightiest power of the North, and cowed the Scandinavian kings: the towns of Swabia and the Rhine formed great commercial leagues, maintained regular wars against the counter-associations of the nobility, and seemed at one time, by an alliance with the Swiss, on the point of turning West Germany into a federation of free municipalities.

Financial distress

Feudalism, however, was still too strong; the cavalry of the nobles was irresistible in the field, and the thoughtless Wenzel let slip a golden opportunity of repairing the losses of two centuries. After all, the Empire was perhaps past redemption, for one fatal ailment paralyzed all its efforts. The Empire was poor. The crown lands, which had suffered heavily under Frederick II, were further usurped during the confusion that followed; till at last, through the reckless prodigality of sovereigns who sought only their immediate interest, little was left of the vast and fertile domains along the Rhine from which the Saxon and Franconian Emperors had drawn the chief part of their revenue. Regalian rights, the second fiscal resource, had fared no better—tolls, customs, mines, rights of coining, of harbouring Jews, and so forth, were either seized or granted away: even the advowsons of churches had been sold or mortgaged; and the imperial treasury depended mainly on an inglorious traffic in honours and exemptions. Things were so bad under Rudolf that the electors refused to make his son Albert king of the Romans, declaring that, while Rudolf lived, the public revenue which with difficulty supported one monarch, could much less maintain two at the same time. Sigismund told his Diet, ‘Nihil esse imperio spoliatius, nihil egentius, adeo ut qui sibi ex Germaniæ principibus successurus esset, qui præter patrimonium nihil aliud habuerit, apud eum non imperium sed potius servitium sit futurum.’ Patritius, the secretary of Frederick III, declared that the revenues of the Empire scarcely covered the expenses of its ambassadors. Poverty such as these expressions point to, a poverty which became greater after each election, not only involved the failure of the attempts which were sometimes made to recover usurped rights, but put every project of reform within or war without at the mercy of a jealous Diet. The three orders of which that Diet consisted, electors, princes, and cities, were mutually hostile, and by consequence selfish; their niggardly grants did no more than keep the Empire from dying of inanition.

Charles IV (A.D. 1347-1378), and his electoral constitution

The changes thus briefly described were in progress when Charles the Fourth, king of Bohemia, son of that blind king John of Bohemia who fell at Cressy, and grandson of the Emperor Henry VII, was chosen to ascend the throne. His skilful and consistent policy aimed at settling what he perhaps despaired of reforming, and the famous instrument which, under the name of the Golden Bull, became the corner-stone of the Germanic constitution, confessed and legalized the independence of the electors and the powerlessness of the crown. The most conspicuous defect of the existing system was the uncertainty of the elections, followed as they usually were by a civil war. It was this which Charles set himself to redress.

German kingdom not originally elective

The kingdoms founded on the ruins of the Roman Empire by the Teutonic invaders presented in their original form a rude combination of the elective with the hereditary principle. One family in each tribe had, as the offspring of the gods, an indefeasible claim to rule, but from among the members of such a family the warriors were free to choose the bravest or the most popular as king. That the German crown came to be purely elective, while in France, Castile, Aragon, England, and most other European states, the principle of strict hereditary succession established itself, was due to the failure of heirs male in three successive dynasties; to the restless ambition of the nobles, who, since they were not, like the French, strong enough to disregard the royal power, did their best to weaken it; to the intrigues of the churchmen, zealous for a method of appointment prescribed by their own law and observed in capitular elections; to the wish of the Popes to gain an opening for their own influence and make effective the veto which they claimed; above all, to the conception of the imperial office as one too holy to be, in the same manner as the regal, transmissible by blood. Had the German, like other feudal kingdoms, remained merely local, feudal, and national, it would without doubt have ended by becoming a hereditary monarchy. Transformed as it was by the Roman Empire, this could not be. The headship of the human race being, like the Papacy, the common inheritance of all mankind, could not be confined to any family, nor pass like a private estate by the ordinary rules of descent.

Electoral body in primitive times

The right to choose the war-chief belonged, in the earliest ages, to the whole body of freemen. Their suffrage, which must have been very irregularly exercised, became by degrees vested in their leaders, but the assent of the multitude, although ensured already, was needed to complete the ceremony. It was thus that Henry the Fowler, and St. Henry, and Conrad the Franconian duke were chosen. Though even tradition might have commemorated what extant records place beyond a doubt, it was commonly believed, till the end of the sixteenth century, that the elective constitution had been established, and the privilege of voting confined to seven persons, by a decree of Gregory V and Otto III, which a famous jurist describes as ‘lex a pontifice de imperatorum comitiis lata, ne ius eligendi penes populum Romanum in posterum esset.’ St. Thomas says, ‘Election ceased from the times of Charles the Great to those of Otto III, when Pope Gregory V established that of the seven princes, which will last as long as the holy Roman Church, who ranks above all other powers, shall have judged expedient for Christ’s faithful people.’ Since it tended to exalt the papal power, this fiction was accepted, no doubt honestly accepted, and spread abroad by the clergy. And indeed, like so many other fictions, it had a sort of foundation in fact. The death of Otto III, the fourth of a line of monarchs among whom son had regularly succeeded to father, threw back the crown into the gift of the nation, and was no doubt one of the chief causes why it did not in the end become hereditary.

Encroachments of the great nobles

Thus, under the Saxon and Franconian sovereigns, the throne was theoretically elective, the assent of the chiefs and their followers being required, though little more likely to be refused than it was to an English or a French king; practically hereditary, since both of these dynasties succeeded in occupying it for four generations, the father procuring the son’s election during his own lifetime. And so it might well have continued, had the right of choice been retained by the whole body of the aristocracy. But at the election of Lothar II, A.D. 1125, we find a certain small number of magnates exercising the so-called right of prætaxation; that is to say, choosing alone the future monarch, and then submitting him to the rest for their approval. A supreme electoral college, once formed, had both the will and the power to retain the crown in their own gift, and still further exclude their inferiors from participation. So before the end of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, two great changes had passed upon the ancient constitution. It had become a fundamental doctrine that the Germanic throne, unlike the thrones of other countries, was purely elective: nor could the influence and the liberal offers of Henry VI prevail on the princes to abandon what they rightly judged the keystone of their powers. And at the same time the right of prætaxation had ripened into an exclusive privilege of election, vested in a small body: the assent of the rest of the nobility being at first assumed, finally altogether dispensed with. On the double choice of Richard and Alfonso, A.D. 1264, the only question was as to the majority of votes in the electoral college: neither then nor afterwards was there a word of the rights of the other princes, counts and barons, important as their voices had been two centuries earlier.

The Seven Electors

The origin of that college is a matter somewhat intricate and obscure. It is mentioned A.D. 1152, and in somewhat clearer terms in 1198, as a distinct body; but without anything to shew who composed it. First in A.D. 1265 does a letter of Pope Urban IV say that by immemorial custom the right of choosing the Roman king belonged to seven persons, the seven who had just divided their votes on Richard of Cornwall and Alfonso of Castile. Of these seven, three, the archbishops of Mentz, Treves, and Cologne, pastors of the richest Transalpine sees, represented the German church: the other four ought, according to the ancient constitution, to have been the dukes of the four nations, Franks, Swabians, Saxons, Bavarians, to whom had also belonged the four great offices of the imperial household. But of these dukedoms the two first named were now extinct, and their place and power in the state, as well as the household offices they had held, had descended upon two principalities of more recent origin, those, namely, of the Palatinate of the Rhine and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. The Saxon duke, though with greatly narrowed dominions, retained his vote and office of arch-marshal, and the claim of his Bavarian compeer would have been equally indisputable had it not so happened that both he and the Palsgrave of the Rhine were members of the great house of Wittelsbach. That one family should hold two votes out of seven seemed so dangerous to the state that it was made a ground of objection to the Bavarian duke, and gave an opening to the pretensions of the king of Bohemia, who, though not properly a Teutonic prince, might on the score of rank and power assert himself the equal of any one of the electors.

Golden Bull of Charles IV, A.D. 1356

The dispute between these rival claimants, as well as all the rules and requisites of the election, were settled by Charles the Fourth in the Golden Bull, thenceforward a fundamental law of the Empire. He decided in favour of Bohemia, of which he was then king; fixed Frankfort as the place of election; named the archbishop of Mentz convener of the electoral college; gave to Bohemia the first, to the Count Palatine the second place among the secular electors. A majority of votes was in all cases to be decisive. As to each electorate there was attached a great office, it was supposed that this was the title by which the vote was possessed; though it was in truth rather an effect than a cause. The three prelates were archchancellors of Germany, Gaul and Burgundy, and Italy respectively: Bohemia cupbearer, the Palsgrave seneschal, Saxony marshal, and Brandenburg chamberlain.

Eighth Electorate

These arrangements, under which disputed elections became far less frequent, remained undisturbed till A.D. 1618, when on the breaking out of the Thirty Years’ War the Emperor Ferdinand II by an unwarranted stretch of prerogative deprived the Palsgrave Frederick (king of Bohemia, and husband of Elizabeth, the daughter of James I of England) of his electoral vote, and transferred it to his own partisan, Maximilian of Bavaria. At the peace of Westphalia the Palsgrave was reinstated as an eighth elector, Bavaria retaining her place.

Ninth Electorate

The sacred number having been once broken through, less scruple was felt in making further changes. In A.D. 1692, the Emperor Leopold I conferred a ninth electorate on the house of Brunswick Lüneburg, which was then in possession of the duchy of Hanover, and succeeded to the throne of Great Britain in 1714; and in A.D. 1708, the assent of the Diet thereto was obtained. It was in this way that English kings came to vote at the election of a Roman Emperor.

It is not a little curious that the only potentate who still continues to entitle himself Elector should be one who never did (and of course never can now) join in electing an Emperor, having been under the arrangements of the old Empire a simple Landgrave. In A.D. 1803, Napoleon, among other sweeping changes in the Germanic constitution, procured the extinction of the electorates of Cologne and Treves, annexing their territories to France, and gave the title of Elector, as the highest after that of king, to the duke of Würtemburg, the Margrave of Baden, the Landgrave of Hessen-Cassel, and the archbishop of Salzburg. Three years afterwards the Empire itself ended, and the title became meaningless.

As the Germanic Empire is the most conspicuous example of a monarchy not hereditary that the world has ever seen, it may not be amiss to consider for a moment what light its history throws upon the character of elective monarchy in general, a contrivance which has always had, and will probably always continue to have, seductions for a certain class of political theorists.

Objects of an elective monarchy: how far attained in Germany

First of all then it deserves to be noticed how difficult, one might almost say impossible, it was found to maintain in practice the elective principle. In point of law, the imperial throne was from the tenth century to the nineteenth absolutely open to any orthodox Christian candidate. But as a matter of fact, the competition was confined to a few very powerful families, and there was always a strong tendency for the crown to become hereditary in some one of these. Thus the Franconian Emperors held it from A.D. 1024 till 1125, the Hohenstaufen, themselves the heirs of the Franconians, for a century or more; the house of Luxemburg (kings of Bohemia) enjoyed it through three successive reigns, and when in the fifteenth century it fell into the tenacious grasp of the Hapsburgs, they managed to retain it thenceforth (with but one trifling interruption) till it vanished out of nature altogether.

Choice of the fittest

Therefore the chief benefit which the scheme of elective sovereignty seems to promise, that of putting the fittest man in the highest place, was but seldom attained, and attained even then rather by good fortune than design.

Restraint of the sovereign

No such objection can be brought against the second ground on which an elective system has sometimes been advocated, its operation in moderating the power of the crown, for this was attained in the fullest and most ruinous measure. We are reminded of the man in the fable, who opened a sluice to water his garden, and saw his house swept away by the furious torrent. The power of the crown was not moderated but destroyed. Each successful candidate was forced to purchase his title by the sacrifice of rights which had belonged to his predecessors, and must repeat the same shameful policy later in his reign to procure the election of his son. Feeling at the same time that his family could not make sure of keeping the throne, he treated it as a life-tenant is apt to treat his estate, seeking only to make out of it the largest present profit. And the electors, aware of the strength of their position, presumed upon it and abused it to assert an independence such as the nobles of other countries could never have aspired to.

Recognition of the popular will

Modern political speculation supposes the method of appointing a ruler by the votes of his subjects, as opposed to the system of hereditary succession, to be an assertion by the people of their own will as the ultimate fountain of authority, an acknowledgment by the prince that he is no more than their minister and deputy. To the theory of the Holy Empire nothing could be more repugnant. This will best appear when the aspect of the system of election at different epochs in its history is compared with the corresponding changes in the composition of the electoral body which have been described as in progress from the ninth to the fourteenth century. In very early times, the tribe chose a war chief, who was, even if he belonged to the most noble family, no more than the first among his peers, with a power circumscribed by the will of his subjects. Several ages later, in the tenth and eleventh centuries, the right of choice had passed into the hands of the magnates, and the people were only asked to assent. In the same measure had the relation of prince and subject taken a new aspect. We must not expect to find, in such rude times, any very clear apprehension of the technical quality of the process, and the throne had indeed become for a season so nearly hereditary that the election was often a mere matter of form. But it seems to have been regarded, not as a delegation of authority by the nobles and people, with a power of resumption implied, but rather as their subjection of themselves to the monarch who enjoys, as of his own right, a wide and ill-defined prerogative. In yet later times, when, as has been shewn above, the assembly of the chieftains and the applauding shout of the host had been superseded by the secret conclave of the seven electoral princes, the strict legal view of election became fully established, and no one was supposed to have any title to the crown except what a majority of votes might confer upon him.

Conception of the electoral function

Meantime, however, the conception of the imperial office itself had been thoroughly penetrated by religious ideas, and the fact that the sovereign did not, like other princes, reign by hereditary right, but by the choice of certain persons, was supposed to be an enhancement and consecration of his dignity. The electors, to draw what may seem a subtle, but is nevertheless a very real distinction, selected, but did not create. They only named the person who was to receive what it was not theirs to give. God, say the mediæval writers, not deigning to interfere visibly in the affairs of this world, has willed that these seven princes of Germany should discharge the function which once belonged to the senate and people of Rome, that of choosing his earthly viceroy in matters temporal. But it is immediately from Himself that the authority of this viceroy comes, and men can have no relation towards him except that of obedience. It was in this period, therefore, when the Emperor was in practice the mere nominee of the electors, that the belief in this divine right stood highest, to the complete exclusion of the mutual responsibility of feudalism, and still more of any notion of a devolution of authority from the sovereign people.

General results of Charles IV’s policy

Peace and order appeared to be promoted by the institutions of Charles IV, which removed one fruitful cause of civil war. But these seven electoral princes acquired, with their extended privileges, a marked and dangerous predominance in Germany. They were to enjoy full regalian rights in their territories; causes were not to be evoked from their courts, save when justice should have been denied: their consent was necessary to all public acts of consequence. Their persons were held to be sacred, and the seven mystic luminaries of the Holy Empire, typified by the seven lamps of the Apocalypse, soon gained much of the Emperor’s hold on popular reverence, as well as that actual power which he lacked. To Charles, who viewed the German Empire much as Rudolf had viewed the Roman, this result came not unforeseen. He saw in his office a means of serving personal ends, and to them, while appearing to exalt by elaborate ceremonies its ideal dignity, he deliberately sacrificed what real strength was left. The object which he sought steadily through life was the prosperity of the Bohemian kingdom, and the advancement of his own house. In the Golden Bull, whose seal bears the legend,—

‘Roma caput mundi regit orbis frena rotundi,’

there is not a word of Rome or of Italy. To Germany he was indirectly a benefactor, by the foundation of the University of Prague, the mother of all her schools: otherwise her bane. He legalized anarchy, and called it a constitution. The sums expended in obtaining the ratification of the Golden Bull, in procuring the election of his son Wenzel, in aggrandizing Bohemia at the expense of Germany, had been amassed by keeping a market in which honours and exemptions, with what lands the crown retained, were put up openly to be bid for. In Italy the Ghibelines saw, with shame and rage, their chief hasten to Rome with a scanty retinue, and return from it as swiftly, at the mandate of an Avignonese Pope, halting on his route only to traffic away the last rights of his Empire. The Guelf might cease to hate a power he could now despise.

Thus, alike at home and abroad, the German king had become practically powerless by the loss of his feudal privileges, and saw the authority that had once been his parcelled out among a crowd of greedy and tyrannical nobles. Meantime how had it fared with the rights which he claimed by virtue of the imperial crown?