Editor’s Note: The following comprises the eleventh chapter of The Holy Roman Empire, by James Bryce (published 1871). All spelling in the original.

(Continued from Part 10)

CHAPTER XI

THE EMPERORS IN ITALY: FREDERICK BARBAROSSA

Frederick of Hohenstaufen, 1152-1189

The reign of Frederick the First, better known under his Italian surname Barbarossa, is the most brilliant in the annals of the Empire. Its territory had been wider under Charles, its strength perhaps greater under Henry the Third, but it never appeared in such pervading vivid activity, never shone with such lustre of chivalry, as under the prince whom his countrymen have taken to be one of their national heroes, and who is still, as the half-mythic type of Teutonic character, honoured by picture and statue, in song and in legend, through the breadth of the German lands. The reverential fondness of his annalists and the whole tenour of his life go far to justify this admiration, and dispose us to believe that nobler motives were joined with personal ambition in urging him to assert so haughtily and carry out so harshly those imperial rights in which he had such unbounded confidence. Under his guidance the Transalpine power made its greatest effort to subdue the two antagonists which then threatened and were fated in the end to destroy it—Italian nationality and the Papacy.

His relations to the Popedom

Even before Gregory VII’s time it might have been predicted that two such potentates as the Emperor and the Pope, closely bound together, yet each with pretensions wide and undefined, must ere long come into collision. The boldness of that great pontiff in enforcing, the unflinching firmness of his successors in maintaining, the supremacy of clerical authority, inspired their supporters with a zeal and courage which more than compensated the advantages of the Emperor in defending rights he had long enjoyed. On both sides the hatred was soon very bitter. But even had men’s passions permitted a reconciliation, it would have been found difficult to bring into harmony adverse principles, each irresistible, mutually destructive. As the spiritual power, in itself purer, since exercised over the soul and directed to the highest of all ends, eternal felicity, was entitled to the obedience of all, laymen as well as clergy; so the spiritual person, to whom, according to the view then universally accepted, there had been imparted by ordination a mysterious sanctity, could not without sin be subject to the lay magistrate, be installed by him in office, be judged in his court, and render to him any compulsory service. Yet it was no less true that civil government was indispensable to the peace and advancement of society; and while it continued to subsist, another jurisdiction could not be suffered to interfere with its workings, nor one-half of the people be altogether removed from its control. Thus the Emperor and the Pope were forced into hostility as champions of opposite systems, however fully each might admit the strength of his adversary’s position, however bitterly he might bewail the violence of his own partisans. There had also arisen other causes of quarrel, less respectable but not less dangerous. The pontiff demanded and the monarch refused the lands which the Countess Matilda of Tuscany had bequeathed to the Holy See; Frederick claiming them as feudal suzerain, the Pope eager by their means to carry out those schemes of temporal dominion which Constantine’s donation sanctioned, and Lothar’s seeming renunciation of the sovereignty of Rome had done much to encourage. As feudal superior of the Norman kings of Naples and Sicily, as protector of the towns and barons of North Italy who feared the German yoke, the successor of Peter wore already the air of an independent potentate.

Contest with Hadrian IV

No man was less likely than Frederick to submit to these encroachments. He was a sort of imperialist Hildebrand, strenuously proclaiming the immediate dependence of his office on God’s gift, and holding it every whit as sacred as his rival’s. On his first journey to Rome, he refused to hold the Pope’s stirrup, as Lothar had done, till Pope Hadrian the Fourth’s threat that he would withhold the crown enforced compliance. Complaints arising not long after on some other ground, the Pope exhorted Frederick by letter to shew himself worthy of the kindness of his mother the Roman Church, who had given him the imperial crown, and would confer on him, if dutiful, benefits still greater. This word benefits—beneficia—understood in its usual legal sense of ‘fief,’ and taken in connection with the picture which had been set up at Rome to commemorate Lothar’s homage, provoked angry shouts from the nobles assembled in diet at Besançon; and when the legate answered, ‘From whom, then, if not from our Lord the Pope, does your king hold the Empire?’ his life was not safe from their fury. On this occasion Frederick’s vigour and the remonstrances of the Transalpine prelates obliged Hadrian to explain away the obnoxious word, and remove the picture. Soon after the quarrel was renewed by other causes, and came to centre itself round the Pope’s demand that Rome should be left entirely to his government. Frederick, in reply, appeals to the civil law, and closes with the words, ‘Since by the ordination of God I both am called and am Emperor of the Romans, in nothing but name shall I appear to be ruler if the control of the Roman city be wrested from my hands.’ That such a claim should need assertion marks the change since Henry III; how much more that it could not be enforced. Hadrian’s tone rises into defiance; he mingles the threat of excommunication with references to the time when the Germans had not yet the Empire. ‘What were the Franks till Zacharias welcomed Pipin? What is the Teutonic king now till consecrated at Rome by holy hands? The chair of Peter has given, and can withdraw its gifts.’

With Pope Alexander III

The schism that followed Hadrian’s death produced a second and more momentous conflict. Frederick, as head of Christendom, proposed to summon the bishops of Europe to a general council, over which he should preside, like Justinian or Heraclius. Quoting the favourite text of the two swords, ‘On earth,’ he continues, ‘God has placed no more than two powers: above there is but one God, so here one Pope and one Emperor. The Divine Providence has specially appointed the Roman Empire as a remedy against continued schism.’ The plan failed; and Frederick adopted the candidate whom his own faction had chosen, while the rival claimant, Alexander III, appealed, with a confidence which the issue justified, to the support of sound churchmen throughout Europe. The keen and long doubtful strife of twenty years that followed, while apparently a dispute between rival Popes, was in substance an effort by the secular monarch to recover his command of the priesthood; not less truly so than that contemporaneous conflict of the English Henry II and St. Thomas of Canterbury, with which it was constantly involved. Unsupported, not all Alexander’s genius and resolution could have saved him: by the aid of the Lombard cities, whose league he had counselled and hallowed, and of the fevers of Rome, by which the conquering German host was suddenly annihilated, he won a triumph the more signal, that it was over a prince so wise and so pious as Frederick. At Venice, who, inaccessible by her position, maintained a sedulous neutrality, claiming to be independent of the Empire, yet seldom led into war by sympathy with the Popes, the two powers whose strife had roused all Europe were induced to meet by the mediation of the doge Sebastian Ziani. Three slabs of red marble in the porch of St. Mark’s point out the spot where Frederick knelt in sudden awe, and the Pope with tears of joy raised him, and gave the kiss of peace. A later legend, to which poetry and painting have given an undeserved currency, tells how the pontiff set his foot on the neck of the prostrate king, with the words, ‘The lion and the dragon shalt thou trample under feet.’ It needed not this exaggeration to enhance the significance of that scene, even more full of meaning for the future than it was solemn and affecting to the Venetian crowd that thronged the church and the piazza. For it was the renunciation by the mightiest prince of his time of the project to which his life had been devoted: it was the abandonment by the secular power of a contest in which it had twice been vanquished, and which it could not renew under more favourable conditions.

Revival of the study of the civil law

Authority maintained so long against the successor of Peter would be far from indulgent to rebellious subjects. For it was in this light that the Lombard cities appeared to a monarch bent on reviving all the rights his predecessors had enjoyed: nay, all that the law of ancient Rome gave her absolute ruler. It would be wrong to speak of a re-discovery of the civil law. That system had never perished from Gaul and Italy, had been the groundwork of some codes, and the whole substance, modified only by the changes in society, of many others. The Church excepted, no agent did so much to keep alive the memory of Roman institutions. The twelfth century now beheld the study cultivated with a surprising increase of knowledge and ardour, expended chiefly upon the Pandects. First in Italy and the schools of the South, then in Paris and Oxford, they were expounded, commented on, extolled as the perfection of human wisdom, the sole, true, and eternal law. Vast as has been the labour and thought expended from that time to this in the elucidation of the civil law, the most competent authorities declare that in acuteness, in subtlety, in all those branches of learning which can subsist without help from historical criticism, these so-called Glossatores have been seldom equalled and never surpassed by their successors. The teachers of the canon law, who had not as yet become the rivals of the civilian, and were accustomed to recur to his books where their own were silent, spread through Europe the fame and influence of the Roman jurisprudence; while its own professors were led both by their feeling and their interest to give to all its maxims the greatest weight and the fullest application. Men just emerging from barbarism, with minds unaccustomed to create and blindly submissive to authority, viewed written texts with an awe to us incomprehensible. All that the most servile jurists of Rome had ever ascribed to their despotic princes was directly transferred to the Cæsarean majesty who inherited their name. He was ‘Lord of the world,’ absolute master of the lives and property of all his subjects, that is, of all men; the sole fountain of legislation, the embodiment of right and justice. These doctrines, which the great Bolognese jurists, Bulgarus, Martinus, Hugolinus, and others who constantly surrounded Frederick, taught and applied, as matter of course, to a Teutonic, a feudal king, were by the rest of the world not denied, were accepted in fervent faith by his German and Italian partisans. ‘To the Emperor belongs the protection of the whole world,’ says bishop Otto of Freysing. ‘The Emperor is a living law upon earth.’ To Frederick, at Roncaglia, the archbishop of Milan speaks for the assembled magnates of Lombardy: ‘Do and ordain whatsoever thou wilt, thy will is law; as it is written, “Quicquid principi placuit legis habet vigorem, cum populus ei et in eum omne suum imperium et potestatem concesserit.” The Hohenstaufen himself was not slow to accept these magnificent ascriptions of dignity, and though modestly professing his wish to govern according to law rather than override the law, was doubtless roused by them to a more vehement assertion of a prerogative so hallowed by age and by what seemed a divine ordinance.

Frederick in Italy

That assertion was most loudly called for in Italy. The Emperors might appear to consider it a conquered country without privileges to be respected, for they did not summon its princes to the German diets, and overawed its own assemblies at Pavia or Roncaglia by the Transalpine host that followed them. Its crown, too, was theirs whenever they crossed the Alps to claim it, while the elections on the banks of the Rhine might be adorned but could not be influenced by the presence of barons from the southern kingdom. In practice, however, the imperial power stood lower in Italy than in Germany, for it had been from the first intermittent, depending on the personal vigour and present armed support of each invader. The theoretic sovereignty of the Emperor-king was nowise disputed: in the cities toll and tax were of right his: he could issue edicts at the Diet, and require the tenants in chief to appear with their vassals. But the revival of a control never exercised since Henry IV’s time, was felt as an intolerable hardship by the great Lombard cities, proud of riches and population equal to that of the duchies of Germany or the kingdoms of the North, and accustomed for more than a century to a turbulent independence. For republicanism and popular freedom Frederick had little sympathy.

Rome under Arnold of Brescia

At Rome the fervent Arnold of Brescia had repeated, but with far different thoughts and hopes, the part of Crescentius. The city had thrown off the yoke of its bishop, and a commonwealth under consuls and senate professed to emulate the spirit while it renewed the forms of the primitive republic. Its leaders had written to Conrad III, asking him to help them to restore the Empire to its position under Constantine and Justinian; but the German, warned by St. Bernard, had preferred the friendship of the Pope. Filled with a vain conceit of their own importance, they repeated their offers to Frederick when he sought the crown from Hadrian the Fourth. A deputation, after dwelling in highflown language on the dignity of the Roman people, and their kindness in bestowing the sceptre on him, a Swabian and a stranger, proceeded, in a manner hardly consistent, to demand a largess ere he should enter the city. Frederick’s anger did not hear them to the end: ‘Is this your Roman wisdom? Who are ye that usurp the name of Roman dignities? Your honours and your authority are yours no longer; with us are consuls, senate, soldiers. It was not you who chose us, but Charles and Otto that rescued you from the Greek and the Lombard, and conquered by their own might the imperial crown. That Frankish might is still the same: wrench, if you can, the club from Hercules. It is not for the people to give laws to the prince, but to obey his mandate.’ This was Frederick’s version of the ‘Translation of the Empire.’

The Lombard Cities

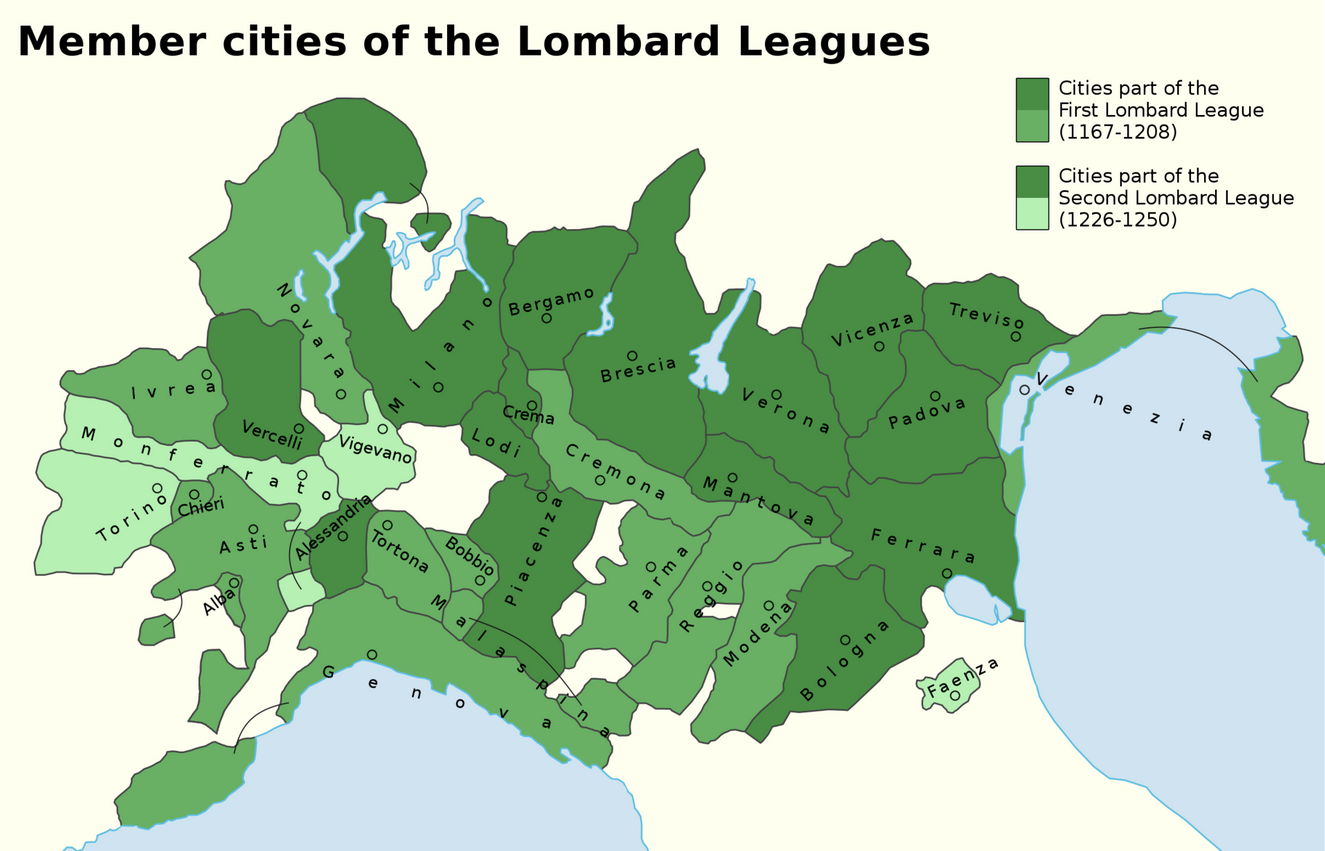

He who had been so stern to his own capital was not likely to deal more gently with the rebels of Milan and Tortona. In the contest by which Frederick is chiefly known to history, he is commonly painted as the foreign tyrant, the forerunner of the Austrian oppressor, crushing under the hoofs of his cavalry the home of freedom and industry. Such a view is unjust to a great man and his cause. To the despot liberty is always licence; yet Frederick was the advocate of admitted claims; the aggressions of Milan threatened her neighbours; the refusal, where no actual oppression was alleged, to admit his officers and allow his regalian rights, seemed a wanton breach of oaths and engagements, treason against God no less than himself. Nevertheless our sympathy must go with the cities, in whose victory we recognize the triumph of freedom and civilization. Their resistance was at first probably a mere aversion to unused control, and to the enforcement of imposts less offensive in former days than now, and by long dereliction apparently obsolete. Republican principles were not avowed, nor Italian nationality appealed to. But the progress of the conflict developed new motives and feelings, and gave them clearer notions of what they fought for. As the Emperor’s antagonist, the Pope was their natural ally: he blessed their arms, and called on the barons of Romagna and Tuscany for aid; he made ‘The Church’ ere long their watchword, and helped them to conclude that league of mutual support by means whereof the party of the Italian Guelfs was formed. Another cry, too, began to be heard, hardly less inspiriting than the last, the cry of freedom and municipal self-government—freedom little understood and terribly abused, self-government which the cities who claimed it for themselves refused to their subject allies, yet both of them, through their divine power of stimulating effort and quickening sympathy, as much nobler than the harsh and sterile system of a feudal monarchy as the citizen of republican Athens rose above the slavish Asiatic or the brutal Macedonian. Nor was the fact that Italians were resisting a Transalpine invader without its effect; there was as yet no distinct national feeling, for half Lombardy, towns as well as rural nobles, fought under Frederick; but events made the cause of liberty always more clearly the cause of patriotism, and increased that fear and hate of the Tedescan for which Italy has had such bitter justification.

Temporary success of Frederick

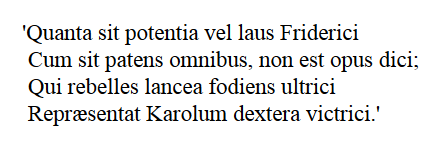

The Emperor was for a time successful: Tortona was taken, Milan razed to the ground, her name apparently lost: greater obstacles had been overcome, and a fuller authority was now exercised than in the days of the Ottos or the Henrys. The glories of the first Frankish conqueror were triumphantly recalled, and Frederick was compared by his admirers to the hero whose canonization he had procured, and whom he strove in all things to imitate. ‘He was esteemed,’ says one, ‘second only to Charles in piety and justice.’ ‘We ordain this,’ says a decree: ‘Ut ad Caroli imitationem ius ecclesiarum statum reipublicæ et legum integritatem per totum imperium nostrum servaremus.’ But the hold the name of Charles had on the minds of the people, and the way in which he had become, so to speak, an eponym of Empire, has better witnesses than grave documents. A rhyming poet sings:—

The diet at Roncaglia was a chorus of gratulations over the re-establishment of order by the destruction of the dens of unruly burghers.

Victory of the Lombard league

This fair sky was soon clouded. From her quenchless ashes uprose Milan; Cremona, scorning old jealousies, helped to rebuild what she had destroyed, and the confederates, committed to an all but hopeless strife, clung faithfully together till on the field of Legnano the Empire’s banner went down before the carroccio of the free city. Times were changed since Aistulf and Desiderius trembled at the distant tramp of the Frankish hosts. A new nation had arisen, slowly reared through suffering into strength, now at last by heroic deeds conscious of itself. The power of Charles had overleaped boundaries of nature and language that were too strong for his successor, and that grew henceforth ever firmer, till they made the Empire itself a delusive name. Frederick, though harsh in war, and now balked of his most cherished hopes, could honestly accept a state of things it was beyond his power to change: he signed cheerfully and kept dutifully the peace of Constance, which left him little but a titular supremacy over the Lombard towns.

Frederick as German king

At home no Emperor since Henry III had been so much respected and so generally prosperous. Uniting in his person the Saxon and Swabian families, he healed the long feud of Welf and Waiblingen: his prelates were faithful to him, even against Rome: no turbulent rebel disturbed the public peace. Germany was proud of a hero who maintained her dignity so well abroad, and he crowned a glorious life with a happy death, leading the van of Christian chivalry against the Mussulman. Frederick, the greatest of the Crusaders, is the noblest type of mediæval character in many of its shadows, in all its lights.

Legal in form, in practice sometimes almost absolute, the government of Germany was, like that of other feudal kingdoms, restrained chiefly by the difficulty of coercing refractory vassals. All depended on the monarch’s character, and one so vigorous and popular as Frederick could generally lead the majority with him and terrify the rest. A false impression of the real strength of his prerogative might be formed from the readiness with which he was obeyed. He repaired the finances of the kingdom, controlled the dukes, introduced a more splendid ceremonial, endeavoured to exalt the central power by multiplying the nobles of the second rank, afterwards the ‘college of princes,’ and by trying to substitute the civil law and Lombard feudal code for the old Teutonic customs, different in every province. If not successful in this project, he fared better with another.

The German cities

Since Henry the Fowler’s day towns had been growing up through Southern and Western Germany, especially where rivers offered facilities for trade. Cologne, Treves, Mentz, Worms, Speyer, Nürnberg, Ulm, Regensburg, Augsburg, were already considerable cities, not afraid to beard their lord or their bishop, and promising before long to counterbalance the power of the territorial oligarchy. Policy or instinct led Frederick to attach them to the throne, enfranchising many, granting, with municipal institutions, an independent jurisdiction, conferring various exemptions and privileges; while receiving in turn their good-will and loyal aid, in money always, in men when need should come. His immediate successors trode in his steps, and thus there arose in the state a third order, the firmest bulwark, had it been rightly used, of imperial authority; an order whose members, the Free Cities, were through many ages the centres of German intellect and freedom, the only haven from the storms of civil war, the surest hope of future peace and union. In them national congresses to this day sometimes meet: from them aspiring spirits strive to diffuse those ideas of Germanic unity and self-government, which they alone have kept alive. Out of so many flourishing commonwealths, four have been spared by foreign conquerors and faithless princes. To the primitive order of German freemen, scarcely existing out of the towns, except in Swabia and Switzerland, Frederick further commended himself by allowing them to be admitted to knighthood, by restraining the licence of the nobles, imposing a public peace, making justice in every way more accessible and impartial. To the south-west of the green plain that girdles in the rock of Salzburg, the gigantic mass of the Untersberg frowns over the road which winds up a long defile to the glen and lake of Berchtesgaden. There, far up among its limestone crags, in a spot scarcely accessible to human foot, the peasants of the valley point out to the traveller the black mouth of a cavern, and tell him that within Barbarossa lies amid his knights in an enchanted sleep, waiting the hour when the ravens shall cease to hover round the peak, and the pear-tree blossom in the valley, to descend with his Crusaders and bring back to Germany the golden age of peace and strength and unity. Often in the evil days that followed the fall of Frederick’s house, often when tyranny seemed unendurable and anarchy endless, men thought on that cavern, and sighed for the day when the long sleep of the just Emperor should be broken, and his shield be hung aloft again as of old in the camp’s midst, a sign of help to the poor and the oppressed.

(Continue to Part 12)

(Continue to Part 12)