Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Triggernometry: A Gallery of Gunfighters, by Eugene Cunningham (published 1934).

He was a man before he was done being a boy. That was at once Bill Longley’s fate and the explanation of this “big old He” of the long line of Texas gunmen, for — even more than Cullen Baker — Longley was Number One of the modern gunslingers.

He was a child of the Texas frontier. Upon him environment cut like a lathe-tool. Born October 6, 1851, on Mill Creek in Austin County, at the age of two he was taken by that God-fearing veteran of Houston’s army, Campbell Longley his father, to Old Evergreen in Washington (now Lee) County.

He was ten when the Civil War got fully underway. Old enough to understand the bitter feeling between the two factions which, in Lee County as elsewhere in Texas, were local typifications of the North and the South. Old enough to understand the fury of the secessionists when Campbell Longley voted the Union ticket, a rage checked before it reached the stage of killing only by the San Jacinto record of young Bill’s quiet, determined father.

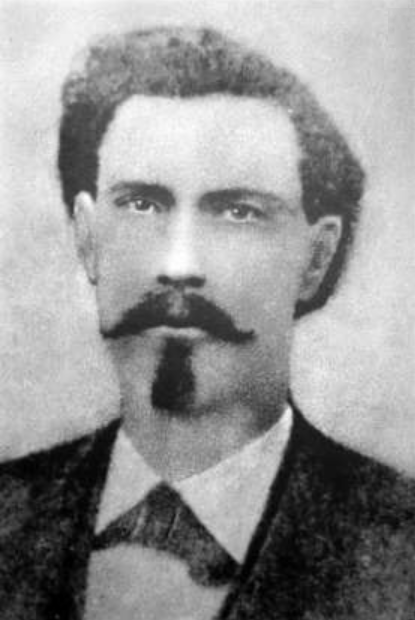

Bill Longley was always large for his age. Six feet tall from his fifteenth year, his weight at maturity was to be two hundred pounds so magnificently proportioned as to make him look slender. He was the idol of the boys at Evergreen’s field schoolhouse. Dark-eyed, dark-haired, his Indian-like face could smile or lower in the same minute. He rode like a Comanche. He could not remember when the “hogleg” shaped butt of the Colt’s pistol was not familiar to his hard big palm.

Behind him was the background of the Texas pioneer who had asked no odds of anything that ran or walked or crept or flew. The Texan of incredible deeds — of the Alamo, of San Jacinto. This young gamecock being bred by quiet old Campbell Longley had in him the fiery independence of habit in thought and action which made the Texan of the ’30s onward an adventurer, a hell-for-leather fighting man, whose superior has never been seen.

He was raw material at fourteen, but destined to be graved into what he became without much more delay, for the South’s second war began with ending of its first, a savage guerilla war, fought never on a formal battlefield, but in a thousand desperate, bloody skirmishes, marked by bloody cruelty on both sides.

In Evergreen, the tiny community flanking the Austin-Brenham road, Bill Longley was a leading spirit among the younger generation. His size, his courage, his amazing skill with twin Colts, a certain fierce elan which was never to desert him, made him a marked figure among the gatherings at the crossroads blacksmith shop and store, under the wide shade of the court house oak — which had served both as justice court and gallows, in its day, and which still stands a brooding giant over that quiet land.

The carpetbaggers and the negroes were the problems discussed at these gatherings of the disfranchised whites. The older negroes were giving no trouble. But the younger freed men were drunk with liberty and license. Incited to swaggering insolence by the riffraff whites in power, protected by troops against prosecution for any crime, they were intolerable to the intensely proud people who were being stupidly affronted by the worst element among their conquerors.

When a week’s tale of outrages major and minor was told, with the sullenly hopeless reflection added, that no legal process, no orderly method, of recourse was available to the outraged, then the human, the natural, reaction among a people of unbroken iron temper was the impulse to hit back.

The stage was set. Bill Longley, standing under the court house oak, with unwavering dark stare going from one face to another, was in the grip of shaping events which — he proved later by his letters — he understood not at all. All he knew was that conditions were such that no white man of any pride of race or history could endure them. He was no philosopher, no thinker. His brain was director of that magnificent body of his, no tool for abstract thought.

Bill Longley… There are old men yet alive who squint across the mists of a long half-century and see him as he was in his heyday. Hunkering in the sun with back to some corral, they mutter his name in their beards and recount the Longley legends. He rides again, gigantic on phantom caballo, across the blue-bonneted prairie, smoke wreathing from the muzzles of his Colts, the elfin echo of his fierce yell carrying to us, as once it carried thunderously into the cabins of the negroes and sent them cowering and mumbling to the shadowed corners….

He belongs to Texan folklore. Upon his shoulders — wide, now, as even those of the towering “Pecos Bill” of the Southwestern range’s legend — are hung apocryphal tales borrowed from the Dick Turpin legend, from Robin Hood. Disregarding these incidents charged to him, he stands at the head of a long procession of Texas gunmen, slingers of the sixes who were to set style and pace for the Genus Gunfighter elsewhere on the frontier that stretched from Montana to Mexico, from Mississippi to California.

He is the major figure of the beginning of the Gunman Cycle that roughly embraced the span of years be tween 1860 and 1900, the period in which amazing skill in the mechanics of pistol-handling was developed, when gunplay became a be-all, end-all, an art separate from the business of mere promiscuous killing.

A loud-voiced negro sat his horse on the Camino Real, the ancient Royal Highway of the Spanish, which ran from Bastrop to Nacogdoches. He was cursing certain white men of the Evergreen neighborhood. Beyond him Bill Longley lounged in his saddle, hands held loosely on the great horn, listening.

“And Campbell Longley,” the negro took up another name. He cursed Bill Longley’s father — but only for a sentence. The huge sixteen-year-old had moved. Down to the curving butts of the Colts sagging on his thighs his hands flashed. The negro saw and loud in the silence his hands slapped the stock of the rifle across his lap.

“Don’t you move that gun!” Bill Longley snarled at him.

But the rifle lifted. Bill Longley spurred his horse and it leaped forward, turned sideway with knee-pressure and slight body-swaying of its rider. The rifle whanged! but the whirling horse had carried Bill Longley clear. Back it spun and as it straightened out into a gallop, Longley fired. The negro came sideway, sliding out of the saddle with a bullet hole through his head.

Sure that no second shot was needed, Bill Longley pushed the Colts back into their holsters. He took down the lariat from his saddle and shook out a loop. He tossed it deftly, to encircle the dead man’s neck. He dragged the body off the road and to a shallow ditch. Here he buried it. His first….

He formed a partnership with Johnson McKowen, to race fast ponies. The Longley-McKowen quarter-horses had a reputation. They went to one race-meeting and found the negroes outnumbering the whites. The dangerous partnership ponies had to be withdrawn. To the partners, that evening, came the word that the negroes were celebrating at Lexington. Longley’s dark stare narrowed as he looked at McKowen. His partner nodded. That was all.

When Lexington with good dark had become a bedlam of singing, shouting, drunken blacks, the two grim faced boys pulled in at the edge of the milling crowd. Longley stared at the saturnalia for a little while. Then, without warning to McKowen, he dropped knotted bridle reins on his horse’s neck. Out came the matched six-shooters. With a yell so high and fierce that it overbore even the howlings of the celebrants, Longley rammed in the spurs. He charged into the crowd before Mc Kowen could move.

It seemed pure madness — suicide. Above the bobbing heads Longley reared gigantic, deadly. But pistols began to flame, the reports so swift that they had the sound of a stick rattled upon a picket-fence. It was incredible that still the lone white face should rear above that dark sea. But Longley’s guns were roaring. He roweled the rearing, maddened horse against the crowd, shooting down those who reached to pull him from the saddle. Miraculously, he plowed on, to emerge from the mass of frenzied negroes. Not a wound was on him, but two men lay dead in his wake and a half-dozen were wounded.

Thereafter, Bill Longley was held in superstitious fear by the negroes. From mouth to mouth his name was passed, the tales of his exploits swelling. He was invulnerable to lead or steel. The very horse he rode was not the same as other horses. A witch-horse, a devil-horse. There was a porter on the Houston and Texas Central Railroad who made it a point to show his authority to white passengers. Upon a certain trip he was much annoyed by the pair of booted feet projecting into the aisle as he moved back and forth. Twice, three times, even a fourth time, he told that passenger to keep his feet out of the aisle. But the fifth time, he kicked them violently out of the way.

He went on, then, to the day-coach. Here he told the conductor all about it and finished on the triumphant note of the kicking. The conductor nodded carelessly: “He always puts his feet in the aisle when he’s riding the train,” he told the porter. “Bill Longley does.”

The porter made a low, agonized, moaning sound and leaped for the rear of the coach. His face, the color of cold wood ashes, hung upon his shoulder as he raced for the rear platform. He leaped for the ground, rolled over, got up and went at stumbling run for the brush. It made no difference that the passenger was not Longley.

A few months after the Lexington episode, or in Mid-December 1866, Bill Longley was taking his alert ease in Evergreen. To him, where he sat talking with several young men, came one of the boys of the place. He was excited. Longley eyed him curiously.

“Three bad niggers down at the saloon, Bill,” the boy gasped. “They’re drinkin’. They’re huntin’ trouble. They’re talkin’ mighty big about hearin’ that Evergreen’s a bad place for niggers an’ they’d like to see somebody make it bad for them!”

Bill Longley got up and mechanically looked to the hang of the six-shooters that sagged on his thighs. The others got up. Like Bill, they twitched the six-shooters they wore to positions more convenient for the draw. But the negroes were already mounted, turning away from the door of the saloon there by the motte of live oaks.

“Get your horses, boys,” said Longley. “We’ll just follow ’em and take those guns off ’em.”

But the negroes had a good lead. They were across the line in Burleson County, more than seven miles away, when the young Evergreen men overhauled them. They whirled with the sound of the drumming hoofbeats. They turned their weapons on the galloping riders. The boys yelled fiercely and bent a little forward, spurring hard.

“Drop those guns!” Bill Longley’s yell crossed the distance between the two parties.

One negro, bolder or drunker than the rest, answered with a shot. But the heat of the liquor in his companions had given way to the chill of that December day — and the chill of sure death that came from the pistol-muzzles that menaced them. The man who had fired grunted and pitched slantingly forward out of the saddle, stone-dead. Longley and his fellows took the other negroes’ pistols and turned back.

Christmas Day dawned. To Bill Longley came the word that a deputy sheriff and posse were coming fast and quietly into Evergreen, to arrest him for the negro’s death. He went out and saddled his horse. He was gone when the posse arrived.

For the moment, Washington County was inconveniently warm for Longley. Early in ’68 he drifted west to punch cows in Karnes County. Riding through York town, a bunch of Federal soldiers mistook him for a friend of his, Charley Taylor. They chased Longley but he was splendidly mounted and the lead from his six shooter buzzed close enough to the Federal heads to weigh down their bridle-reins and blunt their spurs.

The sergeant in charge of the detachment was as well mounted as Longley. And a bold man. He overhauled the fugitive steadily. Five miles, six miles, they raced. Longley had one shot left. He watched the sergeant coming up. When the soldier came stirrup-to-stirrup with him, Longley lunged out with the pistol. The hammer caught in the sergeant’s coat. Longley jerked it back, to free it. There was an explosion and the sergeant fell dead from the saddle.

That ended the pursuit. Longley jogged into Evergreen, but left quickly for Arkansas, for the word was out against him. It was almost fatal for a white man to kill a negro, but when he had also killed a soldier, he had no chance at all, in the Texas of that day.

On the road he met a pleasant young fellow named Johnson and after some talk, they decided to ride together for a while. Longley went home with this personable young fellow — and that night the cabin was surrounded by vigilantes. Johnson was a horse-thief and those frontiersmen in the posse were firm believers in the adage covering birds of a feather, Longley’s protests availed nothing. He was taken with Johnson out into the woods. Behind them, unobserved, a boy came creeping, the small brother of Johnson.

The grim business of noosed ropes and led horses was soon arranged. Young horse-thief, young rebel, they sat beneath one limb with ropes about their necks. Not yet seventeen, but with five notches on his pistols, Bill Longley was face-to-face with Fate.

At a brief word from the leader, the horses were led out from under the prisoners, the condemned. There was a jerk and two bodies, one smallish, one big-limbed, heavy, kicked at the ends of the ropes. Then the vigilantes, turning away, gave the “salute” that was so often farewell to just such writhing forms, over all the frontier. They fired a ragged volley in the general direction of the condemned.

They were hardly out of sight in the brush when a strand of the rope that held up Longley snapped and curled loosely. He weighed over two hundred pounds and in the convulsions of strangulation that great weight became dynamic, jerking on the bullet-weakened manila. Another strand cracked — and another. Bill Longley dropped heavily to the ground, to twitch and writhe against the still-tight noose.

Out of the bushes came the boy who had followed and watched horror-stricken while his brother and Longley were being hanged. He raced to Longley’s side and loosened the strangling noose. He cut the lashings from Longley’s wrists. The world came back to Bill Longley. Fate had struck but glancingly, that time. But only for him. When he cut Johnson down, the horse-thief was dead.

For days Longley hid near the Johnson cabin, fed by the family. Then he joined the desperate band of Cullen M. Baker, robbers, killers, in what they called guerilla warfare against carpet-baggers, negroes and Northern sympathizers. He rode on various raids with the Baker gang.

There came a day in the Spring of ’68 when the Bakers rounded up some of those vigilantes who had hung Longley and Johnson. One witless prisoner bragged about it and told of firing the final shots at the swinging bodies. Up into the forefront of the captors pushed a huge figure, with a grim dark face and glare that must have stricken the boaster dumb.

“I want this fellow!” Longley told Cullen Baker. “I want him right where he did this shooting at us…”

The prisoner was taken to the tree on which Longley and young Johnson had dangled. That night’s business was reenacted, but this time it was the vigilante who was dragged from the saddle under that sinister limb. And when Bill Longley, vindictively bent on revenging himself for the night when he, casual acquaintance of Johnson, was made to share the criminal’s fate, emptied his six-shooter, he took very good care not to hit that rope with a bullet.

Sixteen and a half, now, but a veteran warrior…. A savage youngster, shaped by a savage environment. A tooth for a tooth was the border-code — or, better still, two teeth for one! Riding that summer with Cullen Baker and his mates, he must have shared in their killings of eight to ten men whom they called enemies. But heavy rewards were posted by the Federal troops for Cullen Baker. Longley slipped away and back to Old Evergreen.

If this grim, deadly youngster, marvelously adept at weapon-play, had any notion of settling quietly down, he gave it up speedily. Sheridan had been removed from his command of Louisiana and Texas. But his successor, the humane and sensible Hancock, could not satisfy the rabid bloody shirt element in Congress. Apathy on the part of Texans greeted the attempts at forming a constitution. The military still ruled; Governor Pease was controlled by army officers. Soldiers were police, everywhere.

They chivvied Bill Longley and his brother-in-law, John Wilson, back and forth. The negroes, who trembled at the mere name “Longley,” set soldiers on the pair’s trail. Seven or eight negroes died that summer, when Longley and Wilson struck back. But Bill tired of this life of the hunted wolf. He started for Salt Lake City.

There was one Rector, a trail-driver from Bee County, heading for Kansas. Perhaps Longley would not have joined that outfit had he known of Rector’s violent temper and overbearing habit. But it was a chance to lose himself in the identity of a cowboy and he had to get out of Texas.

The herd rolled on, with Rector ranting at his riders, finding fault with their handling of the cattle, straining already strained tempers to the snapping-point. But he had the name of a dangerous man to cross and he seemed to be the hardest man with his herd. Nobody “called” him until the day when, turning from abuse of a cowboy, he overheard the youngest member of his outfit remarking blandly that he would like to have Rector address him in that manner.

The cowman stood gaping. Resistance from this quarter was the last thing he expected. He was handicapped, standing there in his trail-camp, by ignorance of this level-eyed boy. Asked to name the three most dangerous men in Texas at that time, it is highly doubtful if his list would have included even Ben Thompson of Austin. Certainly, Bill Longley’s name would not have been mentioned. Which was his error. There was no more deadly gunman, none with more of the bulldog’s belligerent readiness to fight, than this huge youngster who faced him now with dark stare. The born fighting machine — that was Longley.

Rector exploded. Longley replied calmly in kind. Finally, they agreed to rather more of formality than was usual. They went out from the herd, each Colt-armed. One might sympathize with Rector, but for his willingness, a grown man, to kill a cocky boy. For he walked to certain death. Longley’s six-shooter came flashing from the holster, hammer back, hammer dropping, hammer lifting-falling-lifting. Six shots he threw at the cowman and the oldtimers tell of it with slow-shaking heads. For they say that Rector had not begun to fall before the sixth bullet had struck him.

Longley left the herd with one of the cowboys. The two encountered a pair of horse-thieves (one wonders if Longley thought of luckless Johnson, swinging in the moonlight….) Longley killed one and delivered the other in Abilene. He stayed only a short while in what was becoming the wildest of towns, the cattle capital of America. He had a brother-in-law in Salt Lake and he wanted to visit him. But before he could get out of Kansas, he had trouble in a Leavenworth saloon.

Trouble! He was magnetized for it… a bulldog in a world of bulldogs. A big, competent, touchy gunfighter, moving over that frontier where the bulk of the population was comprised of seeded men of action — men with something Jovian about them, in that they owned the power to take life, could swagger unafraid with their Colt thunderbolts in each hand. The marvel is that more fatalities are not of record, when such as the Longleys, the Hickoks, the Thompsons, the Hardins, were constantly colliding one with another!

It was a soldier, in the Leavenworth saloon. He looked at the huge youngster, and Longley, product of “reconstructed” Texas, returned the stare darkly with nothing of favor.

“Texas, huh?’’ the soldier remarked. “From Texas…”

“Yes, Texas! And what about it?” Longley demanded.

“Hell of a country!” the soldier informed him. “Every man’s a thief and every woman’s a whore!”

There was the expected, the inevitable, slap of Longley’s hands upon the butts of his ever-loose six-shooters. The soldier slid down the front of the bar with the roar of the right-hand Colt. Longley looked down at him, head on one side. Then he slid, step by step, backward to the door. He ran to his horse and swung up. At the hotel he got his saddlebags.

But this was not Texas, where he knew every foot of the ground, every trick of the pursuing Law. The telegraph wires hummed. He was caught at St. Joseph, taken back to Leavenworth and thrown into the guard house awaiting trial for murder. There was a sergeant whose confidence Longley won. He had money to pay for what he wanted. The two were not long in understanding each other. Longley escaped.

Speed! Speed! He was like a phantom horseman riding hellbent. Every day was sufficient unto itself. Every day might be the last. Fate was riding on the saddle-cantle and perhaps even the wild youth felt the disturbing presence. The restlessness that spurred him on to constant journeying, wild ventures, could be read as chafings against his destiny.

Cheyenne saw him. He joined a party of miners and, when they were turned back from the Big Horn Mountains by the soldiers, he teamed for the government. He opened a saloon in a settlement rejoicing in the name of Miner’s Delight. He became a corral-boss for the army quartermaster. The quartermaster, one Gregory, is alleged to have initiated Longley into the mysteries of tangled and crooked red tape. But they quarreled over a division of spoils when the pupil became so apt that he would rob, not only the Government, but his accomplice. Gregory, like the luckless Rector, misjudged his foe. He came hunting Longley, armed. He died without knowing what had killed him. For Longley “dry gulched him.”

Longley, riding a Government mule, did not wait to see if Gregory would recover consciousness long enough to tell the tale of the shooting. He headed for Salt Lake City and was overtaken by cavalrymen. For nine months he was under guard. Once he escaped but was recaptured after a long pursuit.

At last, he was tried and convicted of the killing and sentenced to imprisonment for thirty years. While awaiting transfer to the Iowa State Prison, he made a daring escape and for a year lived as one of the Snake Indians. It was a wild, free life. One might have expected it to so suit the untamable Longley that he would have ended his days with the tribe. But there is an itching to Texas feet… It drives the Texan out to wander over every land beneath the sun. But, also, it brings him back or, if return be impossible, breaks his heart.

Longley pictured Old Evergreen, the green grove of live oaks and their patriarch, the Court House Oak, with the little stores about them. He saw with the eye of his mind the green sod of the prairies, carpeted by the acre with j blue bonnets. He was homesick as a child.

Back he came, but he dared not come directly. Too much blood lay on the straight trail now. He worked circuitously — the Southwest, where a Mexican girl saved his life, then Kansas — homeward. In Parkersburg, Kansas, he and a young man named Stuart sat down to a card-game. A quarrel developed and Stuart went for his gun. Longley’s speed on the draw came once more into play. Stuart fell across the table with gun unfired, a bullet in his heart, another in his head.

Whatever might have been Bill Longley’s lot, in another environment, different circumstances, he was now definitely on the trail that the James brothers, the Youngers, the Daltons, followed — the trail into other than political outlawry, into criminality.

Killing meant nothing much to such as Longley. He had seen too much of it, done too much of it. Self preservation was strong in his huge body and deadly skill with six-shooter or rifle made it easy. Every man who looked askance at him might be a seeker for that thousand dollars of reward, word of which had trickled to Longley. Any man who put so much as a straw in his path was an enemy — and he knew of but one way to meet an enemy. But from homicide, he was now to turn to its natural corollary — the taking of subsistence from the world in any way that offered.

This Stuart killing — perfectly justifiable in the day and place — brought evidence of the new Longley, who had made his beginning in thievery at the Government corral in Wyoming. For young Stuart’s father offered a reward of fifteen hundred dollars, for the capture of his son’s killer.

They called Longley “Tom Jones”, these days. And when the news of the reward came to him, he went out and found two men to help him in a plan he had conceived. They listened to instructions and grinned. Then they tied up “Tom Jones” and delivered him to the sheriff, claiming the reward. Stuart, senior, came down to look at the slayer of his boy. He handed over the money. The sheriff paid it to the “captors.”

“And that’s that!” he said. They nodded.

“We’ll be saying goodbye to Jones,” one of them suggested. “Where he’s headed, we won’t be seeing him again.”

That was understandable to the sheriff. He led them up to Longley’s cell, to watch this parting. But the grin faded abruptly from his face. Something was poking into his back.

“We’ll just have to cut you off, pocket-high, if you make any noise,” one of the men drawled. “Don’t do it!”

They tied him up and gagged him. They opened up the cell and Longley came out, grinning, with hand out-thrust for the reward. They stood there, with the helpless sheriff in the cell watching, and divided the fifteen hundred. Then they drifted out of town.

Longley and a partner, embarked in a counterfeit scheme and were captured by a Federal Marshal in the Indian Territory. Longley always claimed that it took two thousand in real money to paralyze that officer long enough to let them go. He said that he was dead broke when he continued toward Texas. But home lay ahead, now. He was not worried about money.

Campbell Longley, most tragic figure of the Longley Saga, had found life too hard in Evergreen. He had moved to Bell County to escape if he could the persecution of those who hunted his wolfish son. But whatever peace he found in the new locality was destroyed by Bill’s return.

Word of Bill’s presence on the farm drifted back to Evergreen. A posse came hunting the thousand dollars the state had offered for the young gunfighter. Bill waited only long enough to get a new model Colt six shooter, then “lit a shuck” for Comanche County.

There was a bad negro in that neighborhood, who made a practice of riding up to lonely ranch-houses and ordering white women about. He encountered Longley in a store and pulled his hat down over his eyes.

“Who the hell are you?” he demanded.

“Bill Longley!” replied the young man, with the twinkle of hand-motion that none had ever matched. The new Colt roared twice in the confined space of the little store. Two bullets went through the black desperado’s head.

“These certainly are fine guns!” said Longley, looking at the newly-christened weapon, rather than at the dead man. “They shoot right where you hold ’em!”

He had plenty of friends, who kept him informed of the various movements against him. Word came to him to move west. He made Coleman County, then pushed farther into West Texas. With two companions, he headed for the Colorado River country. Five men overtook the trio, near the Santa Anna Mountains. Longley killed one and the others left that dangerous neighborhood.

Longley, for some reason known to himself only, if to himself, even, went back to the farm in Bell County. But even he could see the impossibility of long escaping capture in that country. He rested a few days and drifted toward Mason County, on the real frontier, where still the Comanches and Kiowas raided every light moon.

[…] (Continued from Part 1) […]