Editor’s Note: The following is from Brave Men and Brave Deeds, by M.B. Synge (published 1907)

Somewhat over a hundred years ago there used to be seen, riding or driving in a rapid manner, on the open roads or through the scraggy woods near Potsdam, a highly interesting, lean, little old man. He had a stooping figure, but seemed none the less alert for that.

He was a king, “every inch of him, though without the trappings of a king.”

He was dressed with Spartan simplicity: an old military cocked hat, trampled and kneaded, took the place of a crown; a walking-stick cut from the woods served as a sceptre; for royal robes he wore merely a soldier’s blue coat with red facings.

And this was no less a man than Frederick the Great of Prussia—at least, so he was known to the world at large; at home among the common people, in his German fatherland, he was only known as “Father Fritz.”

His thin face, with its steadfast grey eyes, bore traces of much sorrow, and gave evidence of much hard labour done in the world. Perhaps his childhood alone and the hardships he endured would account for a good deal.

He was born in the palace of Berlin on a cold January day in the year 1712. Great were the rejoicings when the news spread that a prince was born to the Crown Prince, afterwards Frederick the First; for two little princes had already died: one, it was said, had been killed by the noise of the cannon firing for joy over it; the other was crushed to death by the weighty dress and metal crown put on it at the christening. This little prince too had a narrow escape of being stifled by the somewhat rough caresses of its overjoyed young father.

On Sunday, the last day of the year 1712, at the age of one week, the prince was christened Frederick with great pomp and magnificence. He was not spared the cannon volleys or the metal crown, but he survived them all, and lived to be one of the greatest kings Prussia ever had.

When Frederick was but fourteen months old, his grandfather died, and his father became King of Prussia.

The king seems to have been fond enough of the little Crown Prince Fritz at this time. He was a quiet, rather melancholy child, and very delicate. He was brought up with Spartan simplicity, his food was of the plainest, and he was kept in petticoats and curls for a long time.

To make a soldier of him was his father’s one idea, and great was the king’s joy when one day on his return home he found the small boy beating a drum with evident pleasure.

But the king was destined to disappointment. The Crown Prince was no soldier at this early age.

The king’s idea of what his education should be was written down for the tutors who were to teach the prince.

“He is to learn no Latin, observe that, however it may surprise you,” he writes. “What has a living German man and king of the eighteenth century to do with dead old heathen Latins? Let him learn arithmetic, mathematics, artillery, economy, history in particular, ancient history only slightly, but the history of the last hundred and fifty years to the exactest pitch. Of geography he must know whatever is remarkable in each country.

“The prince must, from youth upwards, be trained to act as officer and general, and to seek all his glory in the soldier’s profession. You must make it your care to stamp into my son a true love for the soldier’s business, and to impress on him that there is nothing in the world can bring a prince renown and honour like the sword.”

Already a miniature soldier company had been formed for the prince, numbering over a hundred. Boys of his own age, selected from noble Prussian families, made up this “Company of Crown Prince Cadets,” as they were called, and the Crown Prince himself was drilled until he could himself take command, in the Prussian uniform of light blue and a cocked hat. He was but ten when the king had a “little arsenal “made for him in the “Orange Hall of the palace,” where, with a few companions, he could mount batteries and fire small brass ordnance. From an early age he accompanied the king on his annual reviews; for from the Russian frontier to the French border every garrison and regiment was rigorously reviewed by the king once a year.

The boy had very little time to call his own. Here is his father’s time-table for his days when he was ten years old:—

“On Monday, as on all week days, he is to be called at six, and so soon as called he is to rise; you are to stand to him, that he do not loiter or turn in bed, but briskly and at once get up and say his prayers. This done, he shall as rapidly as possible get on his shoes and spatter-dashes, also wash his face and hands, but not with soap. Then he shall put on a short dressing-gown, have his hair combed out and queued, but not powdered. While getting combed and queued, he shall at the same time take breakfast of tea, so that both jobs go on at once; and this shall be ended before half-past six. Then enter his tutor and the servants with worship, hymns and prayers follow; this is done by seven, and the servants go again. From seven till nine he learns history, from nine to a quarter to eleven the Christian religion. Then Fritz rapidly washes his face with water, hands with soap and water; clean shirt; powders, and puts on coat; about eleven, comes to the king. Stays with the king till two, perhaps walking a little, dining always at noon. At two he goes back to his room. His tutor is there ready, takes him upon the maps and geography from two to three. From three to four he treats of morality; from four to five lie writes German letters, to acquire a good style. About five Fritz shall wash his hands, and go to the king, ride out, or divert himself in the air and not in his room, and do what he likes, if it is not against God.

“In dressing and undressing, you must accustom him to get out of and into his clothes as fast as is humanly possible. You will also look that he learns to put on and put off his clothes himself, without help from others, and that he be clean and neat, and not so dirty. ‘Not so dirty,’ that is my last word, and here is my signature.”

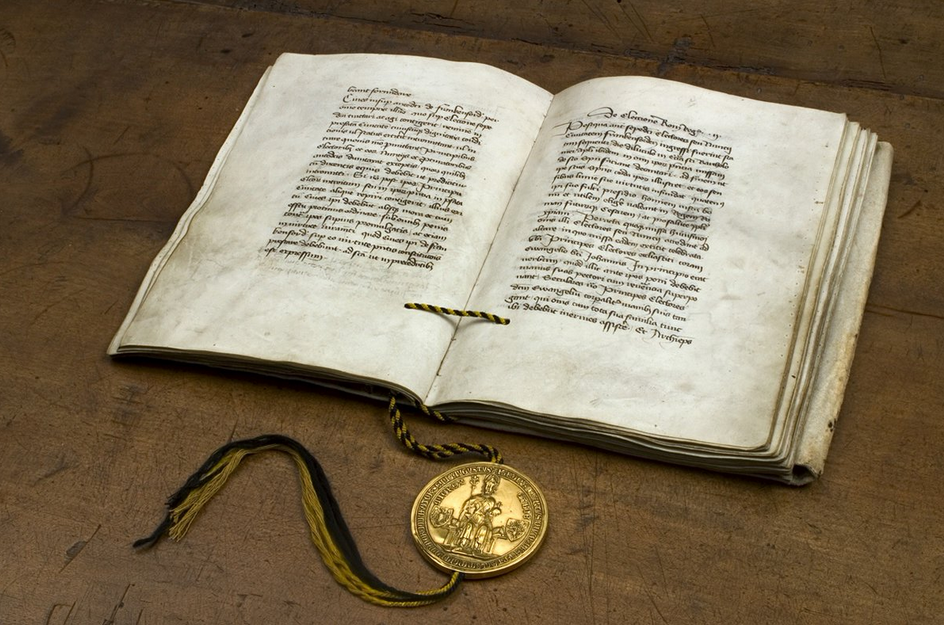

The boy was slow in learning the lessons he did not care about; at spelling he was bad even to the end of his long life. The forbidden Latin had great attractions for him, and he used to make his tutor teach him the language in secret. One day the king was going his rounds when he came upon Fritz and his tutor engaged in this forbidden employment. The table was strewn with Latin books, dictionaries, and grammars, and the Crown Prince was eagerly learning. “What is this?” roared the king, fixing his eyes on a Latin copy of the Golden Bull.

“Your Majesty, I am explaining the Golden Bull to the prince!” exclaimed the trembling tutor.

“Dog, I will ‘Golden Bull’ you!” cried the king. “Go!” And the terrified tutor fled.

This was not the only grievance the king had now to complain of. The boy did not care for hunting; he preferred story-books and flute-playing. He refused to have his hair closely cropped according to army regulation, and, instead, “combed it out like a cockatoo.”

But on this last point the king was firm, and one day the court surgeon, with comb and scissors, was ordered to come and crop the prince’s hair before his father’s eyes.

The boy was growing to have a decided will of his own, which was distasteful to the tyrannical king, and the first rifts of division in the royal household now began to take place. New offences seemed to be added day by day. The king began to hate the Crown Prince, and to long sorrowfully that his younger brother, August William, might be Crown Prince in his stead.

And yet this Fritz, growing daily more out of favour, was to become one of the greatest of the Prussian kings, by whom his angry father would be far out-shadowed one day.

In vain did his mother try to conciliate the king, imploring him to take the Crown Prince back into favour.

“I cannot bear the effeminate fellow,” was the king’s answer, “who has no manly inclinations, who is shy, cannot ride or shoot, is not cleanly in his person, frizzes his hair like a fool, and does not cut it. All this I have reprimanded a thousand times, but all in vain.”

Still the Crown Prince kept his own way.

After devoting a certain time to restraint, to drilling in tight uniforms, he would retire to his room, throw his uniform into a corner, have his hair dressed, put on a gold brocade dressing-gown, and practise on his flute with a great flute-player called Quantz.

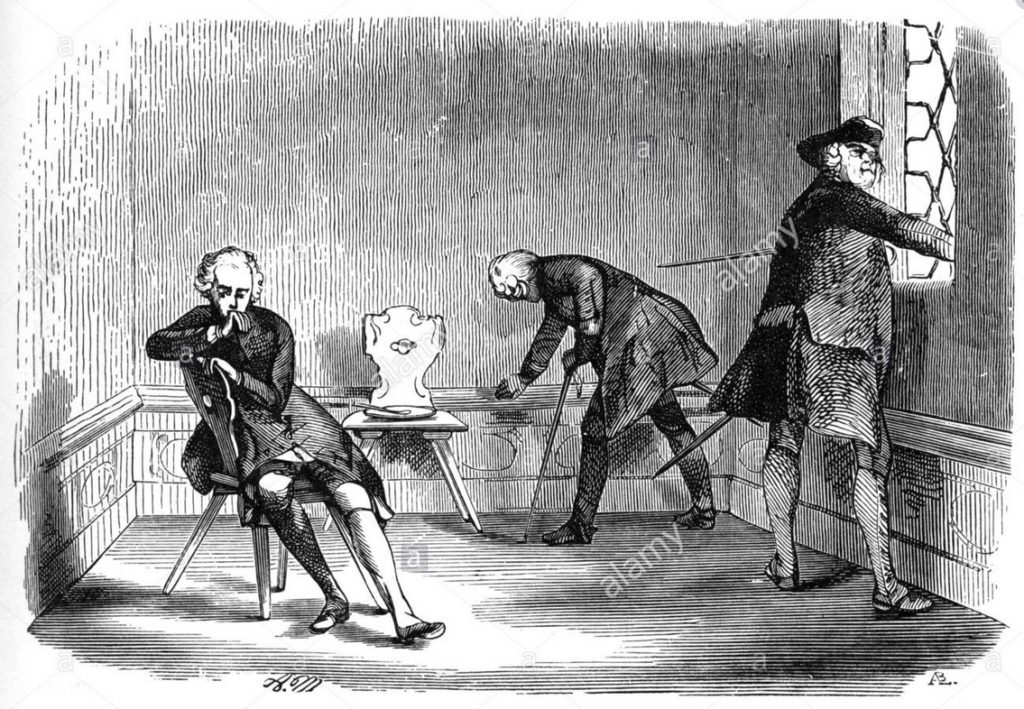

One day he was practising in this manner, when a messenger entered breathlessly to say the king was coming, indeed was close at hand.

Snatching up the flutes and music-books, Quantz had just time to hide himself in a small closet from which the stove was supplied with fuel, while the Crown Prince struggled into his uniform.

The king entered full of suspicion. He saw the state of the case. Looking about, he discovered behind a curtain shelves of books and some handsome dressing-gowns. These he ordered to be burned. Then he stormed at the prince, while Quantz trembled in his hiding-place.

“Fritz is a piper and a poet,” cried the king; “he cares nothing about soldiers, and will undo all that I have been doing.”

The king with his family was at Potsdam, where he had a violent attack of gout in both feet. This made him exceedingly ill-tempered, and his children suffered severely, especially the Crown Prince and his favourite sister Wilhelmina. Here is her account:—

“We were obliged to be in his room by nine in the morning; we dined in it, and durst not leave it on any account. Nothing was to be heard all day but abuse of me and my brother. The king never called me anything but the ‘English brat,’ and my brother ‘that scoundrel Fritz.’ He forced us to eat and drink things which we disliked or which disagreed with us. The king was drawn about in a chair through the whole palace, his two arms being supported by crutches. We had always to follow this triumphal car, like captives about to undergo their sentence. One day, as we rose from table, he aimed a violent blow at me with his crutch.”

Indeed, the royal children in this eighteenth century palace seem to have been treated as no human being would treat a dog or a cat in these days.

The king almost starved them, too. He carved himself, and helped everybody except Wilhelmina and Fritz. He rarely saw the Crown Prince without seizing him by the collar and caning him.

The situation became intolerable to the young man, now close on eighteen. At last he sent a secret letter to his mother. It is dated Potsdam, December 1729:—

“I am in the uttermost despair. The king has entirely forgotten that I am his son. This morning I came into his room as usual. At the first sight of me he sprang forward, seized me by the collar, and struck me a shower of cruel blows. I tried in vain to screen myself, he was in so terrible a rage, almost beside himself; it was only weariness that made him give up.

“I am driven to extremity. I have too much honour to endure such treatment, and I am resolved to put an end to it in one way or another.”

His plans of escape were made, and one night soon after he went into his sister’s room to say good-bye.

“I am come to bid you farewell, my dear sister,” he said. “I go, and do not come back. I cannot endure the usage I suffer; my patience is at an end. I shall get across to England. Calm yourself. We shall soon meet again in places where joy shall succeed our tears, and we shall be free from these persecutions.”

Wilhelmina was stupefied for a moment. Then, seeing the danger of his scheme, she argued with him long into the night till he promised to give up his wild plans, or, anyhow, postpone them.

But by the following year things had reached such a crisis that even Wilhelmina agreed that flight was his only chance. So detestable had the Crown Prince become to his father that one day, on entering the king’s room as usual, he was seized by the hair, dragged to the window, and would soon have been put an end to had not timely help arrived.

“I will tell you secretly of all that happens,” he said miserably to his sister, “and find a safe channel for sending you letters.”

But his escape was badly planned, and the page who was to accompany him, in an agony of remorse, confessed all to the king.

The Crown Prince was arrested and brought back. His long-planned flight had failed; moreover, his condition was worse than before, for he was practically now a prisoner.

Openly the king struck him till the blood ran down his face; his sword was taken from him, and he was treated as a state criminal.

“Why did you run away?” asked the king in a furious voice.

“Because,” replied the prince firmly, “you have not treated me like your son, but like a base slave.”

“Then you are an infamous deserter, who has no honour,” roared the king.

“I have as much as you,” answered the prince, “and I have done no more than I have heard you say a hundred times that you would have done were you in my place.”

The king was beside himself at this answer. He drew his sword, and would have run the prince through had not an old general stepped between them to prevent it.

“If, sire,” he cried, seizing the king’s arm, “you must have blood, stab me. My old body is not good for much; but spare your son!”

The sword was put back; the prince was removed to a separate room, where two sentries with fixed bayonets kept watch over him; and the king did not see him again for a year and three days.

In September he was sent to a fortress some sixty miles from Berlin, and lodged in a strong room there. It consisted of bare walls; there was no furniture; books were forbidden. His sword had been taken from him, every mark of dignity was gone. He was clad in brown prison dress of the plainest cloth; his food was to cost ten-pence a day, and was to be cut up, no knife being allowed him. The room was to be opened morning, noon, and evening, four minutes at a time; the tallow lights were to be extinguished at seven p.m. He was to be alone all day, not even his flute might comfort him through the long and dreary hours.

Yet even this was not enough punishment, in the eyes of the king, for one who had deserted from the Prussian army. A court-martial must try him and his friend Katte, who was mixed up in the plan of escape.

The court-martial sat for six days, and made known the result to the king; that result was, that Katte must die the death of a deserter.

It was in the grey of a winter morning in November 1730 that Katte was led forth past the windows of the prince’s fortress, where the scaffold awaited him.

“Pardon me, dear Katte,” cried the miserable prince, overwhelmed with despair. “Oh, that this should be what I have done for you!”

“Death is sweet for a prince I love so well,” answered Katte bravely as he passed on to his doom.

And the Crown Prince Fritz sank fainting on the floor. So melancholy and unhappy did the prince become that those about him besought the king to have pity on him, lest some dreadful mental malady should come on.

“If the Prince Royal really repents with all his heart of the faults he has committed, and is firmly resolved to amend,” wrote the king to the chaplain, “you will declare to him, in my name, that, though I cannot entirely forgive him, I will mitigate the severity of his confinement. He shall have the town of Custrin for his prison, but he shall not go beyond it.”

The Crown Prince, after taking a solemn oath to submit to the king in all things, was then half released. When the prince heard of his father’s concession, tears came into his eyes.

“Is this possible?” he murmured; and having taken the oath, he added firmly, “I am resolved never to break it.”

Further, he sent a message to his father. “Say,” he said, “I am deeply affected by my father’s goodness, and request him to send me a belt for my sword.”

“What!” exclaimed the king with delight, “is Fritz a soldier?”

On the fifteenth of August, just a year after the unlucky failure of escape, the king thought fit to visit his son in his exile and judge for himself whether he was in a state to be received back into favour. As soon as they met, the Crown Prince fell at his father’s feet. The king, in a stern voice, bade him rise.

“You must recollect what has passed during the last year, and how shamefully you have behaved,” he said. Then he went on to enumerate all his faults, until the prince, in a flood of tears and with deep emotion, kissed the king’s feet. At last the king was touched, and embraced his son, “which gave the prince such delight as no pen is capable of expressing.”

As the first tokens of returning favour, the king, on his return to Potsdam, sent him a carriage and horses, with a promise of soon allowing him to return to the army again.

In November 1731, he was summoned to Berlin to attend the marriage festivities of his sister Wilhelmina. She had suffered much during her brother’s imprisonment, and it was only to help the reconciliation between her father and brother that she consented to become the wife of the Prince of Bayreuth, whom she had never seen. All at once he stood before them.

“See, madam, there is Fritz again!” cried the king, as the prince stood before his astonished sister.

The princess was overcome at seeing him again. “I threw my arms about his neck,” she says, “and was so agitated that I could only utter broken sentences. I cried, I laughed like one out of her senses. I took my brother by the hand and begged the king to love him again; but my brother was as cold as ice and silent.”

The court and the army were rejoiced to see the prince in their midst again.

“Let us have him in the army again, your majesty,” they said. And Fritz was once more allowed to wear the uniform of the Prussian army.

And so the unhappy boyhood of Frederick the Great was ended.

“I have always loved you,” said his father, as the Crown Prince knelt beside his dying bed, “though I have been strict with you. God is very good to give me so excellent and worthy a son.”

Fritz kissed his father’s hand, while his tears fell. The king clasped him in his arms, and pressing him to his bosom, sobbed,—

“O my God, I die content, since I have such a worthy son and successor!”

[…] Source link […]

Alright. Confess your secrets. How did you find all these wonderful tomes? Through research or being the luckiest man on earth?

There is a lot of good Western literature to be found in used book stores, particularly in the antiquarian sections.

Call me crazy, but the king could have achieved his ends much earlier and more easily if he had simply impressed upon his son the duties and the reasons for those duties. Having done so, and provided the prince excelled in his lessons, personal interests could be pursued on the side when time allowed.

Sometimes a harsh upbringing produces strong character in a future leader. And there are hard-headed, rebellious sons so stubborn that no gentle means will correct them. I think both to be true in Frederick’s case.

4