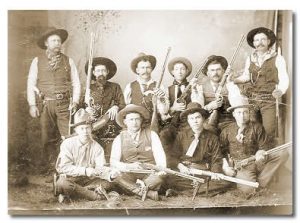

Texas Devils: Rangers and Regulars on the Lower Rio Grande, 1846-1861. By Michael L. Collins. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008. Pp. xi + 316. Illustrations, Acknowledgements, Introduction, Notes, Bibliography, Index. $26.95 cloth.)

Texans normally accept, without question, the mythical status of the Texas Rangers as strong, honorable, tenacious, and dedicated, bringing justice to the oppressed and destruction to the criminal. Collin’s book challenges those descriptions, providing a revisionist history of this storied group of lawmen, focusing upon the era between Texas’ annexation into the United States and its secession from the Union, prior to the Civil War.

While considering the contributions of luminaries from the early days of the Texan Rangers, including Jack Hays, Samuel Walker, John “Rip” Ford, and the interactions that these men had with other historical figures, such as Robert E. Lee and Sam Houston, Collins does not limit his study to these well-known characters, by including the exploits of lesser-known members of the organization. This provides for a balanced analysis of the topic, showing the impact that individual Rangers had on the society and culture of the borderlands between Texas and Mexico.

While considering the contributions of luminaries from the early days of the Texan Rangers, including Jack Hays, Samuel Walker, John “Rip” Ford, and the interactions that these men had with other historical figures, such as Robert E. Lee and Sam Houston, Collins does not limit his study to these well-known characters, by including the exploits of lesser-known members of the organization. This provides for a balanced analysis of the topic, showing the impact that individual Rangers had on the society and culture of the borderlands between Texas and Mexico.

Collins attempts to balance the myth of the Rangers with reality, and is successful on the whole; however, he struggles with consistency in conveying the fact that these men were products of their environment. The book states that there were people on both sides of the border that preyed upon civilians, especially the Tejanos, but it tends to gloss over non-Ranger maltreatment. While the approach provides readers with factual information about shortcomings of these Texas partisans, it would have been beneficial to add details about Mexican instigators and their atrocities in similar fashion.

Though the book challenges the veracity of the stereotypical Texas Ranger identity, it nonetheless recognizes that they were important, contributing to the formation of the borderland culture. Rather than presenting these men in dualistic terms, Collins avoids describing them as being simply good or bad, but recognizes that they were complex men, accomplishing their role in a complex time. For example, while the majority of Rangers were Anglos, and often harbored racist views of their Mexican neighbors, the author mentions that there were Tejano Rangers and that several of the Anglo leaders were married to Tejanas. In this way, the book demonstrates that the relationship between Rangers, Mexicans and Tejanos was composed of many layers, which must be pulled back to allow for careful and accurate study.

Building upon Walter Prescott Webb’s often hagiographical work on the Rangers, Collins provides a correcting view of the place that the Texas Rangers should hold in the study of Texas History. Students should not view them monolithically, but evaluate their actions, both good and bad. Webb’s views are not presented as being totally inaccurate, but simply incomplete. The Rangers often performed brave and noble acts, but they also committed despicable depredations. Texans have normally remembered the nobility, but ignored the negative impact that these men wrought upon their environment. In contrast, Mexicans have remembered the Rangers as los diablos Tejanos—the Texas Devils. It is the juxtaposition of these two collective memories that Collins struggles to reconcile with reality. He argues that both viewpoints contain truth, yet neither is without inaccuracies.

The book’s final pages show that the task is difficult. There is significant evidence that the Rangers were both heroic and savage. Collin’s conclusion is that there were many heroes, but even more villains, within the ranks of this storied organization in its formative years. His purpose is not to detract from the former, but to bring the historical reality of the latter to light. In this way, historians can produce an accurate history of what was accomplished during this important era.

Since the book’s thesis is concerned with the Rangers’ influence on the border region, a reader might be confused by significant sections that look at filibustering attempts in Nicaragua. Collins does show that some of the participants of this Central America campaign were later involved with the Texas Rangers, but the topic does not seem to fit within the context of this work. It distracts the reader from the book’s purpose by introducing several individuals who were involved in an activity that was only peripherally related to the Rangers.

Collins has produced a readable and helpful book. It would be a stronger book if the aforementioned passages that veer off topic were excluded, but his overall purpose of providing a more accurate view of the Texas Rangers is accomplished. It is impossible to ignore the impact that these men had on the history of Texas and Mexico, and this book makes it easier to have a proper understanding of what that impact really was, as viewed from both sides of the border.

5