Southeastern Europe Under Ottoman Rule, 1354-1804. Peter F. Sugar. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1977. 365 pp. $34.95. ISBN 0-295-96033-7

Peter Sugar presents this volume in the History of East Central Europe, providing focus on the Balkans, specifically during the formative years when the Ottoman’s controlled the region. His aim is to “deal with all major aspects of history. Political, social, economic, institutional, and religious aspects” are all given attention (p. xi). In addition, he intends to avoid excessive use of “scholarly apparatus,” so that the volume is accessible to readers who either do not specialize in this region or are students. With those stipulations, he provides an historical overview of Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, Romania, Serbia, Croatia, Hungary, and Turkey, as well as the people that inhabit the region. His purpose is to provide a comprehensive examination of the region, rather than being country-specific (p. ix). This allows the research to focus on “geographical or political units that were significant during the period in question,” rather than according to modern boundaries. Sugar’s goal is that this general study will allow for an increase in the understanding and interest of East Central Europe (specifically the Balkans, in this volume), stimulating further research and study (p. x). In all of his goals, he is spectacularly successful.

The well-organized structure of the book allows the reader, especially one that has limited knowledge of the region to establish a foundation of understanding upon which to continue learning. In that regard, Sugar is spectacularly successful. The chronological approach is easy to follow and allows for a natural flow to the work. At the outset, a good description of fundamental realities of Ottoman society is provided so that the reader will be able to have a framework from which to understand the material that will follow. As the reader progresses through the book, the chapters that follow tend to build upon what was read previously.

The well-organized structure of the book allows the reader, especially one that has limited knowledge of the region to establish a foundation of understanding upon which to continue learning. In that regard, Sugar is spectacularly successful. The chronological approach is easy to follow and allows for a natural flow to the work. At the outset, a good description of fundamental realities of Ottoman society is provided so that the reader will be able to have a framework from which to understand the material that will follow. As the reader progresses through the book, the chapters that follow tend to build upon what was read previously.

Sugar points out major events, people, and transitions that had lasting affect on the region. The ongoing disintegration of Ottoman influence and rule serves as a good example of this. Sugar points out that while the Ottoman millet system began to fail, it was the corruption of governmental officials and their “inability to exercise effective control” in the provinces that really led to the final “disintegration of the administrative, social, and economic structures” (p. 233). By evaluating the millet system and why it failed, Sugar provides the context for how the political corruption and incompetence led to the failure of Ottoman rule. This is in contrast to earlier studies that had considered the millet system to be successful.

In this manner, Sugar demonstrates how the Ottoman Empire was unique, differing from other empires in European history, being more like Arab or Asian empires. The Ottomans expected everyone who lived in the empire to provide useful service to the Empire (p. 273). When it was no longer in the interest of the people to provide such services, the Empire began to fail. Sugar’s ability to lead the reader to these conclusions is well developed and accomplished. His bibliographic essay at the end of the book provides for a more traditional scholarly examination, exhibiting that he used a wealth of resources, many of which where previously unknown to Western readers.

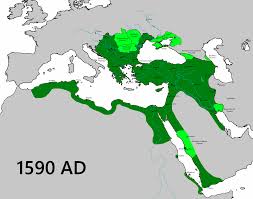

Maps are provided inside the front and back covers, allowing the reader to refer to them easily. Many illustrations and tables are also included that complement the text well. The various appendices provide for a quick reference to timelines, glossaries, and genealogies. All of these supplementary materials help the reader to digest the content that Sugar provides.

For all the good that the book accomplishes, it is limited by shortcomings, such as the author’s inability to read Greek (p. xii). One would think that the scholar who composed a treatise on Greece and other Hellenized regions would have a working knowledge of the Greek language, and Sugar’s lack of knowledge limits the resources that he can use. While the sources he did use were impressive, there are more scholarly works that are outside of his reach, and therefore of the book. Likewise, he was not allowed to research many Turkish resources, because of the Turkish authorities refusal. While not the fault of the author, it does limit what he is able to relay to the reader. These two large omissions of material could lead the reader to think that the book is not complete, only having partial information.

In some parts of the book, Sugar’s writing can be hard to read, due to the heavy language and content; large sections tend to be dry, since it is a textbook. Though targeted at non-specialists and students, Sugar often uses technical jargon, non-English words, and he expects the reader to have a working knowledge of the geographical region. While these shortcomings can be easily overcome, they could be a hindrance for some readers.

Regardless of these minor issues, Sugar has produced a valuable resource for any student who desires to learn of the southeastern portion of Europe during Ottoman Rule. Scholars will find a treasure trove of resources to use and new students will be given a firm foundation upon which to build future studies. The book provides Sugar’s unique interpretation of the Balkans and their history under Ottoman Rule, and is worthy of attention and study. For the scholar who can read Greek or gain access to Turkish records, Sugar points the way for future research to add to the field. Anyone interested in learning about this region will find useful material in the book, though it is best designed to serve as a textbook in graduate study. Though the book demands careful and deliberate reading, the effort is worthwhile, providing the reader with invaluable information. The book is highly recommended, and it should be expected that just as the book as served for over thirty years as the standard for textbooks on the Balkans, it will continue to do so for many more years.