Editor’s note: The following is extracted from One Damned Island After Another, by Clive Howard and Joe Whitley (published 1946).

In the late afternoon of March 27, two men climbed down stiffly from a C-47 transport plane which had just landed on Iwo Jima. They began walking across the runway toward the operations tent.

The two men were Lieutenant Herbert Bowden and Staff Sergeant Tom Hall. Like all people arriving on Iwo for the first time, they noticed the thin wisps of yellow steam rising from the ground and felt the soles of their heavy GI shoes grow warm and then almost hot as they trudged over the ashy surface of the volcanic island.

Bowden, who had been pleasant and talkative on the long plane ride up from Guam, suddenly grew silent.

Hall, filled with the excitement of a newcomer to overseas service, was aware of a peculiar thing happening to himself.

He had found it hard, during the flight from Guam, to focus on the young Lieutenant who sat next to him talking enthusiastically of his plan to open an advertising agency in New York after the war. His mind had been a whirling kaleidoscope of islands, coral runways, water, endless clouds and churning propellers which, in less than two weeks, had carried him almost seven thousand miles from California.

Then, as Sergeant Hall walked his first hundred yards on the island of Iwo Jima, the whirling stopped abruptly and his senses came suddenly, sharply into focus.

Iwo was like that.

“Iwo hit you in the face and kept hitting you,” one Air Forces man said. “Iwo was the end of the world.”

Iwo had hit Lieutenant Bowden and Sergeant Hall the way it hit the Marines who came ashore a month and ten days before; the way it hit the thousands of men who had arrived since D-Day.

Iwo was high-pitched-frantic. It boiled with the noise of men and bulldozers and airplanes. But it was grim and silent and desolate.

On Guam, Bowden and Hall had talked enthusiastically of their assignment. Working for the Intelligence section, they were to handle part of the work necessary to carry out the first Seventh Air Force fighter escort mission over Japan, now less than ten days away. It was a choice assignment.

On Iwo, they talked quietly and dispassionately of the work they could accomplish the next day and, when it grew dark, made their way to the separate quarters assigned them.

Iwo Jima hit Sergeant Hall again while he was putting up his canvas cot.

The men around him, crew chiefs and mechanics, talked of little except the queer sounds that filtered through the ground at night — the muffled clanging of subterranean digging coming from the deep caves where an unknown number of Japs still held out.

Hall noticed that the men around him kept their knives and carbines handy and wished he hadn’t replaced his own gun with a portable typewriter before he left Guam.

Exhausted as he was, it took Hall a long time to fall asleep; he was nagged with an uneasy feeling of impending tragedy.

“Iwo was always like that,” one man said. “If something violent wasn’t happening at the moment, there was a dread sense that it was about to happen.”

There is no coherent account of exactly what happened on Iwo Jima on the night of March 27. There are individual accounts of terrible violence; the babbled, shocked words of the dying; the signs of mortal combat which persisted for a long time.

It was sometime in the early hours before dawn when the distant sounds of gunfire awoke Sergeant Hall. He jerked upright on his cot.

“It’s nothing,” a voice near him said. “Probably just a couple of guards shooting at each other. Happens almost every night.”

The sounds grew louder, closer. Hall, trained as a combat infantryman before he transferred to the air forces, recognized the bursts of grenades and small mortars.

“Jesus!” somebody in the tent yelled. “That’s right in our area.”

In a flash, the tent was empty. Hall, stumbling over cots and duffel bags in his rush toward the door, glimpsed men darting through the moonlight toward a road at the end of the company area.

Two men seemed to be helping another man who, clad only in shorts, stumbled and limped between them. There was blood all over the man’s shorts.

As Hall reached the door, he saw an Army carbine hanging from a nail. He reached for it and then remembered that its owner might come running back for it at a critical moment.

Hall reached the end of the company street behind the group he had been following and dove to the ground after them, burrowing with his arms and legs into the layers of ash.

Over and over again a man next to him was saying hysterically: “The bastards! The dirty bastards! Hundreds of ’em. Hundreds of ’em!”

Hall’s body shook uncontrollably with fear. His arm, flailing in the ash, came to rest for a moment against the body of a husky major dug in next to him. The major’s body was quivering with spasms of terror; his flight coveralls were wet with the sweat of honest fear. Sergeant Hall was no longer ashamed.

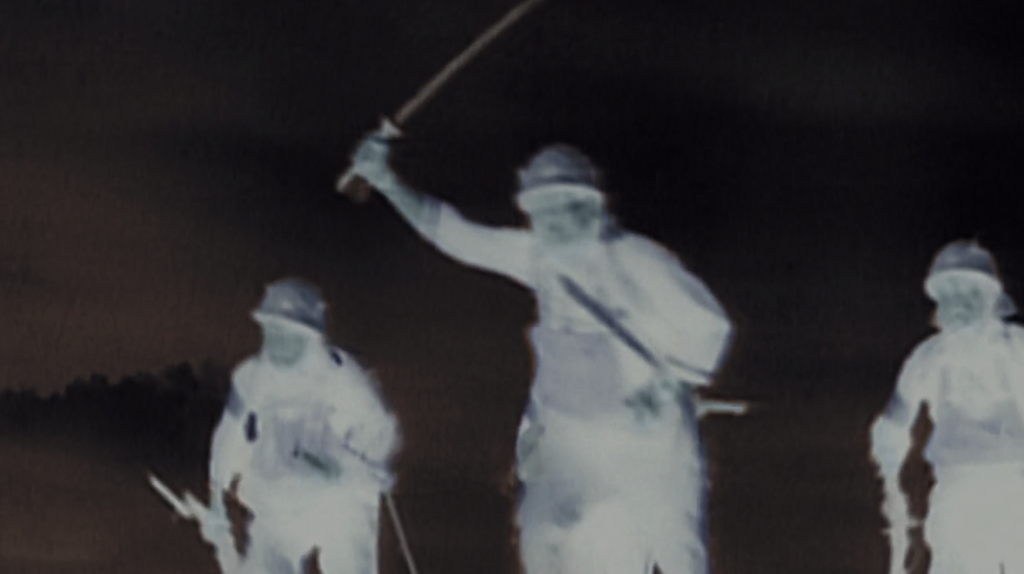

By now, the Japs were everywhere, running from tent to tent, slitting the canvas with swords, tossing grenades through the openings, pouring rifle and machine gun fire into the tents; shouting, laughing, screaming, “Banzai!”

Under a truck parked on a rise of ground a few yards from where Sergeant Hall had taken cover, there were half a dozen pilots pinned down by rifle fire. One of them was Lieutenant Joseph Coons, a twenty-one-year-old fighter pilot who was one of the few people awake when the attack started. Coons, scheduled for a pre-dawn patrol mission, had climbed into the truck and was waiting for it to start for the airstrip when a grenade, probably the signal that launched the attack, went off. He dove under the truck.

“It was pretty dark,” Coons said, “but I could make out a small party of Japs a short distance away. I emptied my .45 in their direction, but I don’t think I hit any of them.

“Japs seemed to come right up out of the ground. In the bivouac area, we could see them milling around the tents, cutting the canvas with swords or lifting the flaps and throwing grenades inside.”

Coons grabbed a rifle just as a Jap raised up from a hole between the truck and the company street. They both fired at the same time. The Jap toppled over; his bullet went wide of Coons and killed another officer in a nearby foxhole. Another Jap got up and started toward the man who had been mortally hit. Coons dropped him with one shot.

Crawling down the incline toward a foxhole, Coons could set into a crater near the bivouac area. He called back for a grenade and flipped it into the crater. Seconds went by before the grenade exploded, and Japs poured from the hole. Coons and the men behind him cut them down.

It was clear that this was no desperate infiltration by a few crazed Japs. It was a carefully planned attack carried out by hundreds of Japs, timed for the critical interval when most of the Marines had been withdrawn and the infantry was on its way in. Its specific purpose seemed to be the decimation of the fighter pilots who, the Japs must have known, were soon going to Tokyo.

The attack carried into every part of the Fighter Command area. As the Japs struck and fled, they discarded their own guns for American weapons and used them with deadly effectiveness.

Most men were caught fast asleep by the raid. A few, awakened by the first sounds of gunfire, managed to get to some kind of cover before the Japs moved in. Most of the pilots were armed only with .45 pistols; some men had army carbines.

Many had no weapons. One armed pilot who apparently decided to risk a sprint up the company street, gained the door of his tent as a Jap was slashing at the canvas with his sword. The Jap whirled and struck the pilot across the head with his saber.

The pilot grabbed his attacker and wrestled him to the ground. Locked in mortal combat, the pilot and the Jap rolled over and over in the ash until the American got his hands around the Jap’s throat. He choked him to death.

A group of cooks, caught without weapons when six Japs stormed their kitchen, seized trays, pots and pans, carving knives and everything that wasn’t nailed down and drove the Japs out.

The night before the attack, there had been an alert. Three Air Forces men, Technical Sergeant Philip Jean (later reported missing in action), Technical Sergeant Albert L. Stein, and Sergeant S. T. Coker, Jr., had made a deal with some Marines to borrow two BAR’s and some ML’s. They were the only adequate combat weapons in the Fighter Command area when the attack opened.

At the sound of the first fire, the men in Jean’s tent dove for their foxhole. In the gathering dawn, they could see Japs working over adjourning areas. Jean and Stein crawled out of their fox hole and began to snake through the ash toward a ridge behind the tent area.

Two Japs suddenly popped out of a hole. One of them raised his arm; there was a grenade in his fist. Jean whirled and poured a stream of BAR fire into the Jap. The Jap fell back into the hole and his exploding grenade killed his companion.

The two Americans gained the ridge, which looked clear of Japs. Jean left Stein on guard with the BAR and, armed only with a .45, moved on into an adjoining tent area. As he stepped around the corner of a tent, he almost stumbled over two wounded Japs crawling for cover. One of them started to raise his rifle. Jean grabbed it by the muzzle, swung it around and blew off its owner’s head. His .45 took care of the second Jap.

A few Marines, attracted by the sounds of battle, began to arrive with BAR’s and machine guns.

A big, hulking Marine Major, running into the area from the road, came upon Sergeant Hall and the half-dozen Air Forces officers still frozen in their shallow holes.

“Three or four Japs still in there,” the Marine Officer said to the men. “We can organize a skirmish line and clean them out. Let’s go!”

“We jumped up and followed the Marine down the company street,” said Sergeant Hall. “I felt silly as hell; I still didn’t have a gun.”

Hall picked up a carbine from the ground just as some Japs at the end of the street opened fire on the group. He ducked behind a big steel can filled with water. A Jap, apparently concealed in a nearby tent, began lobbing grenades. The grenades exploded on the other side of the barrel and Hall made himself very small. It was pretty clear to him that the Marine’s estimate of “three or four Japs” was in error.

“Three hundred was closer to it,” Hall said. “I was lying behind the barrel when a Jap got out of a hole not fifty yards away. I got a perfect bead on him and squeezed the trigger.

“That damned carbine didn’t go off.”

Somebody else, one of the officers who had been dug in with Hall at the end of the street, got the Jap with his .45.

“That Marine guy was magnificent,” Hall said. “He came running from behind a tent, crouched over pouring BAR fire into the crater where the Japs were holed up. Then, quite calmly, he began pegging grenades into that hole.”

The enemy seemed to be concentrated in a pocket-shaped area like a flat V. A call went out for volunteers to clean out the pocket and Technical Sergeant Philip Jean and another man armed with a BAR stepped forward.

Jean crawled into the nearest arm of the V, past a pillbox which had been knocked out. Around the corner of a tent, some Japs had set up a knee mortar and Jean could hear them chattering. He stepped quietly around the corner of the tent and opened fire. He poured out one clip, then a second. Halfway through the third, his gun jammed. It wasn’t until then that he realized he was alone. The other man’s BAR had jammed; he wasn’t able to get off a single round. Jean’s fifty rounds accounted for eight Japs dead and three probables.

As Jean’s fire ceased, Stein, armed only with a .45, walked cautiously forward toward the exact center of the V, where there were still plenty of Japs. Just behind the pile of Japs killed by Jean’s BAR fire, a Jap jumped from a hole, a grenade in each hand. Stein stopped him with two bullets in the head. Just to be sure, he emptied the rest of the clip into the Jap, explaining, later:

“I didn’t think the government would mind wasting the ammo.”

Sergeant Coker, from the same tent as Jean and Stein, was moving up the area about the same time. A Jap got up from behind a bush and started to run. Coker shot him down. Another Jap got up from under a pile of bodies in a gulch, a grenade in his upraised hand. Coker shot him through the head.

In the first, faint gray of dawn, the Army moved up with flame throwing tanks. For a moment, it looked as though the battle would end quickly. But the tanks could not be used; too many Air Forces men were still trapped in their tents.

In one tent, the fighter pilots had rolled from their cots and flattened themselves on the floor. Some Japs piled into a crater just outside the tent and the pilots could hear them talking and yelling.

They tossed grenades at the tent where the flyers were, but the grenades either went off into the air or rolled down the canvas and exploded outside the tent. Then they raked the tent with rifle fire.

Captain R. B. Kessler, one of the men in the tent, heard the sound of ripping canvas. He crawled closer to the door and saw a Jap officer about fifteen feet away, swinging his saber like an axe to rip open the adjoining tent and screaming “Banzai!” at the top of his voice. Kessler took a chance of tipping off his position and fired. The Jap officer fell backward, dead.

One pilot was trapped in the tent which the enemy seized as a command post.

All through the battle, while Japs moved in and out of the tent in a continuous stream, the pilot lay behind an upturned cot, terrified even to move his foot which stuck out in plain sight for fear the Japs would hear the sound.

Trapped in another tent was a group of enlisted men who had slept through the first sounds of gunfire and were awakened by the sounds of Japs talking just outside.

The men in the tent slid quietly out of bed and lay on the floor – all except Sergeant Harry Hamilton, a sound sleeper.

Fully aware of what was happening, the men on the floor wisely refrained from waking up Hamilton. The slightest sound would have drawn fire.

There was a slight, ripping sound and a Jap bayonet was thrust into the tent. It struck a wooden box. The bayonet was withdrawn and plunged into the tent at another spot. Again, it hit a box. It ripped through the tent a third time, waggling in thin air two feet above the nose of Staff Sergeant Ernest Huth.

For a while the Japs seemed to think it was a supply tent. Hamilton slept on.

Apparently the Japs decided to make sure. A saber ripped an opening in the canvas and a grenade hissed through the hole, rolled across the long, narrow tent and stopped under a packing box. The explosion blew Hamilton out of bed. He woke up on the dirt floor with his head ringing. Near him lay a man with a bad leg wound. Hamilton crawled to the man and applied a tourniquet which doctors later said saved his life.

A hail of bullets crashed through the tent at waist height. Outside, Japs were crawling under the outstretched tent ropes, brushing against the canvas sides. The firing receded for a moment and then moved closer again. Rifle barrels appeared through holes at the north and south ends of the tent and raked the double row of cots. One man was mortally wounded; another lay groaning.

The Japs began firing in the direction from which the groaning could be heard.

“There wasn’t time to be gentle,” Hamilton said later. “I gagged the man, applied a tourniquet and made my way to the south end of the tent.”

Hamilton could see a wounded Jap lying outside the door, with two other Japs talking to him. Hamilton raised his carbine silently, took careful aim and pressed the trigger. Nothing happened. The weapon had jammed. He grabbed another carbine and pressed the trigger. It was jammed.

“Son-of-a-Bitch!” Hamilton shouted. The form in the doorway stirred. “Don’t swear like that,” the dying Jap said in a flawless English. “It isn’t nice.”

The other two Japs were under cover now so Hamilton moved back to the center of the tent and cut a small hole in the canvas near the ground. There were seven Japs in a foxhole between Hamilton’s tent and the one adjacent. Hamilton couldn’t fire without endangering the men in the other tent.

On the other side of the tent, Hamilton got his sights on a Jap rifleman. Suddenly a Jap officer popped to his knees; there was a potato-masher grenade in his upraised hand. Hamilton whirled and fired. The officer doubled up, still clutching the grenade. It exploded and blew his face open. The other Japanese soldier guffawed.

A rifleman rose to half crouch, laughing hysterically, digging the ground with his bayonet and brandishing a grenade.

Staff Sergeant Milton Hlebof hit him first. The Jap flinched and laughed.

Corporal Frank B. McCollum raised his carbine and shot eight bullets into the Jap’s chest. Blood gushed from the man’s wounds and a great, spreading stain of red appeared on the Jap’s tunic. Still, he roared with laughter, dug at the ground with his bayonet and brandished the grenade.

Hamilton slid to an opening and fired two shots into the Jap’s chest. He was rewarded with a gale of wild laughter.

Carefully, Hamilton trained his rifle sights on the bridge of the Jap’s nose. Deliberately, he squeezed the trigger.

“The bullet drilled him between the eyes,” Hamilton said. “He collapsed like a rag.”

“He didn’t laugh any more.”

“Somehow,” said Sergeant Robert Fredericks, combat correspondent from whose written report much of this account is taken, “in spite of the battle, in spite of the awful bloodiness, the sun came up over Iwo Jima on the morning of March 28.”

The battle was over. The Jap attacking force had been cut to pieces, although mopping-up operations continued until noon. Jap bodies, 333 of them, sprawled over a wide area of the northwest corner of the island. Eighteen were captured alive. Tents were spattered and soaked with blood.

It wasn’t all Japanese blood. Forty-four officers and enlisted men of the VII Fighter Command and attached units were killed in action. Eighty-eight were wounded.

Shocked and haggard, Sergeant Tom Hall sat limply on his cot as the sun came up and the sounds of gunfire died down on the morning of the twenty-eighth. He supposed that, despite the awful bloodiness and the terrible stench of the dead, the war would go on. Probably, the first fighter escort mission to Japan would come off on schedule.

Hall pulled himself erect and, picking his way around the bodies sprawled in grotesque attitudes all through the area, made his way to the tent where he had left Lieutenant Bowden the night before.

A pilot who sat on the edge of a cot with his head in his hands looked surprised when Hall asked about Bowden. He seemed to have forgotten there was an extra man in the tent that night.

Suddenly, Hall knew.

He turned and walked quickly out of the tent and forced him self to look into a crater where a body lay. The man’s face was shot away, but he was a huge man; Bowden was slender.

Hall ran to another foxhole and again made himself look. There were two dead men in this one; both were Japanese.

The beads of sweat traced thin, white lines in the ashy grime on Hall’s brow. His hands were wet.

He began to run from foxhole to foxhole.

It was a long time before Sergeant Hall could talk about it.

“I found him finally,” he said, slowly. “He was at the bottom of a foxhole. At first, it looked like he was just resting there.”

A flight surgeon told Hall that the end had come swiftly. The bullet had gone through Lieutenant Bowden’s head.