Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Essays and Monographs, by William Francis Allen (published 1890).

It is a little surprising, considering how accurate is our knowledge of the poetry, philosophy, and art, the wars, religion, and political institutions of the ancients, that we have so vague a notion of them as men and women — find it so hard to imagine how they looked, dressed, and lived, how they spent their time, what they thought and talked about, in common every-day affairs. The Greeks and Romans are, after all, very unreal to us — hardly more than names which represent and embody certain conceptions of art, literature, and thought. We know them only in the monuments they have left — the books, statues, and temples; and we scarcely think of them as actually living, any more than these. We see statues of Pitt and Washington, robed in a costume which we know they would have shuddered at; and it is hard to conceive that Demosthenes, Sophocles, and Augustus actually looked as we see them represented in marble. A boy who has labored through Cæsar, Cicero, and Virgil, has an indistinct idea that these men he has been reading about spent their lives in waging war, sitting in the Senate, and founding cities, offering solemn sacrifices to the gods, or attending gladiatorial shows and the games of the Circus. He cannot imagine to himself people talking Latin: that stately tongue seems to him to exist only in periods and hexameters, and to disdain the sordid uses of petty traffic or the trivialities of fashionable small-talk. Nor do books or antiquities help him much. They give, it is true, the dry facts, and these are indispensable materials to a knowledge of the life; but they are only materials, after all — the body without the soul.

Nevertheless, the Romans did have a private and domestic life; their character had a light and amiable aspect, as well as that sterner one which is more familiar. They ate and drank; dressed and bathed; had their clothes washed and mended, and their shoes patched; wore wigs and false teeth. The boys played with marbles, tops, hoops, and balls; the women gossiped and went shopping; the men speculated, drove bargains, and shaved notes,[1] quarrelled, jested, and flirted.

Nothing helps so much to realize the daily life of the ancients as a visit to Pompeii, the city buried by an irruption of Vesuvius, eighteen hundred years ago, and now at last restored to light. Here you enter gateways through which Pompeian gentlemen drove with their wives; you tread streets, paved with solid stone, rutted with the wheels. You enter the doors of houses, over the floors of elegant mosaic, and stand within the walls, in some cases under the roofs, where men and women of that distant age lived. You see what sort of rooms they lived in, the taste with which their walls were adorned — not gaudy, mouldering wall-paper, but exquisite paintings, with colors still bright and forms still distinct. You might see the furniture, too; but it has been removed. to the museum. You enter drinking-shops and bakeries, baths, temples, theatres, forum and exchange, and see the marks of daily life about you— the defacements of ordinary use, even the scribblings and caricatures on the walls. In the great museum of Naples you see the articles that have been removed from these houses chairs and tables of most elegant shape, in bronze or marble (the wood, of course, has perished), kettles, jars, saucepans, steelyards, pitchers, cups, strainers, frying-pans, jelly-moulds, even carbonized loaves of bread; combs, pins, needles, thimbles, locks and keys, saws, planes, spades, pickaxes, chisels, lamps-in short, nearly all the commonest implements of every-day use are found there, many of them the very counterpart of ours, and many much more elegant than we ever see. But these are only the appendages of life, not the life itself.

Whoever shall desire, a hundred or a thousand years hence, to obtain a vivid and accurate picture of the daily life of us who are living now in the middle of the nineteenth century, will not look for it in the historians and poets alone. From Macaulay and Motley, Longfellow, Browning, and Tennyson, he will get one view of it; and, if he could look at it but from one side, that, no doubt, is the one he would choose — just as we would not, if we could, give up the records that we possess of the higher thought of the ancients in exchange for the most intimate acquaintance with their outward habits and manners. But he will not need to stop at this; he will go to our newspapers, novelists, and caricaturists to piece out the partial knowledge of our age which he has obtained from the higher walks of literature. Now of Greek and Roman literature we have hardly anything which represents prose fiction and periodicals; and this is the chief reason that life in antiquity is not made to look natural to us, as ours will to our posterity.

The ancients were not, it is true, entirely destitute of these two branches of literature. There are still extant two or three Roman novels, rather low and grotesque in character, and giving only a very limited view of society; invaluable for the picture of life which they present, if we bear in mind that this picture is at once partial and exaggerated. There was a sort of newspaper, too, in Rome during the Empire, a daily register of all matters of general interest, issued by public authority and called the Acta Diurna. Tacitus, the historian, alludes to it when, apologizing for the barrenness of events of a certain year, he adds that he might have filled up space with a description of the new amphitheatre; but that sort of thing is for the newspapers: it is below the dignity of history. And again, in his eloquent account of the death of Thrasea, the most illustrious of the victims of Nero, the sycophants who accuse Thrasea of treason tell the emperor, in order to inflame his jealousy and suspicion, that in the provinces and the army the journal is read chiefly in order to see how Thrasea votes in the Senate — what measures he disapproves. The satirist Juvenal, too, in describing the cruelty of a noble Roman lady, says that she has her slaves flogged in her presence, while she herself is gossiping with her crony, or admiring a new dress, or reading the news. This morning journal was no doubt copied by hand from the official copy by persons who made this a regular business, and furnished, like books, to wealthy nobles or sent abroad. Would that somebody had thought it worth his while to preserve a file of them for our eyes! After all, they probably contained only a meagre chronicle of events, and would have served us very little in getting at the domestic life of the Romans.

The poets, especially Martial, and the letter-writers abound in the information we are in search of. The light, fashionable poets, not aiming to rival the lofty strains of Homer and Eschylus, but to tickle the ear of the crowd, fill their writings with the jests and repartees and familiar allusions which make up the small-talk of the day. The comedies of Plautus and Terence introduce the men and women of that age before our eyes, and give us their conversation, witty or trivial, often earnest and abounding in matter. But the private letters of Cicero, Pliny, and others are still better fitted to give us an idea of the personality of the best representatives of the Roman character; for Plautus and Terence lay their scenes chiefly among the uncultivated classes; Propertius and Martial delighted in dissolute and fashionable society. But the private correspondence of Cicero and the Younger Pliny is very voluminous, interesting, and instructive. From this we learn of the family relations of these distinguished men, their warm friendships, their elevated thoughts and sentiments, their genial and playful social intercourse, their manner of doing business and their mode of life. Whoever is disgusted with the indecency of Ovid and Petronius, or shocked at the bloodthirsty proscriptions of Sulla and Octavianus, or the terrible scenes of the amphitheatre, should turn to these letters of Cicero to his wife and brother and friend Atticus, or those of Pliny to the Emperor Trajan and the historian Tacitus, to have his faith in humanity quickened.

It has been remarked that, next to the failure to recognize the common element of humanity in different communities and at different ages, there is no more fundamental mistake than not to recognize the essential differences in these different communities and ages. And, when we compare the Greeks and Romans with the civilized people of the present day, we find, perhaps, no more vital cause of contrast — even more striking, perhaps, in manners and customs than in thoughts and feelings — than this that we are farther removed from primitive barbarism than they, by a difference of several hundred years. The Romans were as great barbarians five hundred years before Christ as our ancestors were a thousand years ago. The savage fierceness which only shows itself at rare intervals among Europeans nowadays, when humanity seems cast aside for a time, and man makes himself a beast — as in the French Revolution, the Indian revolt of 1857, the military prisons of Andersonville and Belle Isle, and the massacre at Fort Pillow — this fierceness never wholly disappeared from the Roman character. Humane gentlemen, like Cicero and Pliny, were the exception; for a few such as these the Stoic philosophy had accomplished what Christianity has done for the mass of men in modern times; but of the majority of the Romans it may be said that, with all the externals of civilization, they were through and through barbarians. Napoleon said, “Scratch a Russian, and you find a Tartar.” So with the Romans: the polished, merciful Augustus was only the treacherous, bloody, lustful Octavianus under another name. “It is noble to be avenged on one’s enemies” — this was the sentiment of that model of Roman matrons, Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi.

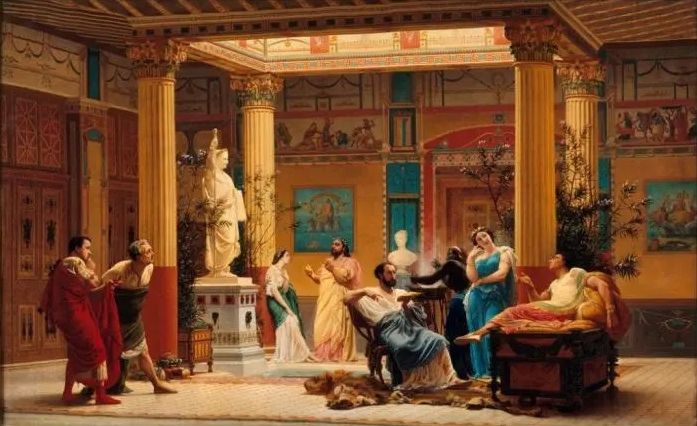

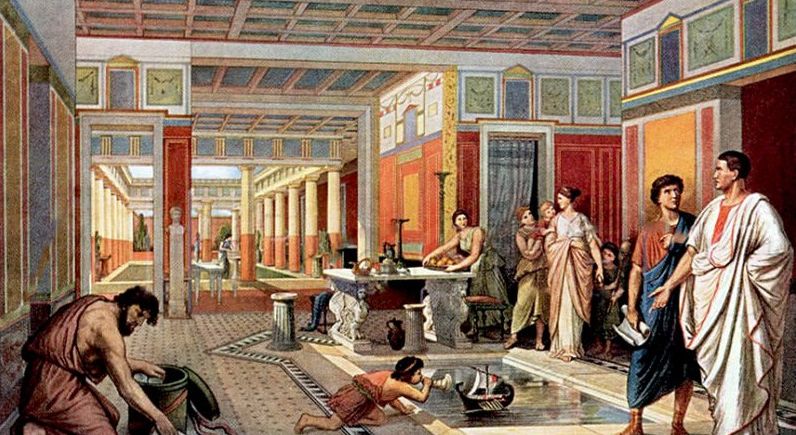

This semi-barbarous nature of the Romans, this nearness in time to the forests in which they had their origin, has wider and more varied effects than one sees at first sight. The Roman house, for instance, never departed very far in principle from the simple cabin in which it took its rise. There was always the one central room, or hall, out of which the smaller rooms opened — the atrium, from ater, black, because its walls were blackened with smoke – which was at once kitchen, dining-room, bedroom, and sitting-room, just as is the case in the log cabins of the present day. But the Romans never wholly outgrew this. When they built larger houses, the atrium was always the chief feature. They had separate sleeping apartments, but here stood the symbolical bed; they had their cooking done out of sight, but here remained the symbolical hearth; they had banqueting-rooms, courts, colonnades, boudoirs, and spacious parlors, but the atrium was always the centre of the house. Here the Roman noble received his clients and friends; here were the images of his ancestors, and all his family heirlooms. The narrow chink in the roof through which the smoke escaped was widened into a broad impluvium; the smoky rafters became cedar beams, carved and gilded, and supported sometimes by marble columns; the earthen floor was laid with mosaic, statues stood between the columns, and the central space, open to the sky, was paved with. even blocks of stone — so the poor dark atrium of Cincinnatus and Fabricius was transformed into an open court, surrounded with cloisters. But, however elegant might be the later ornaments of the hall, there was still always room for the simple waxen images of the forefathers and the rude wooden statuettes of the household gods.

Neither did the Romans ever make common use of chimneys or windows. The hole in the roof was still the outlet for the smoke in most private houses. It must, however, be remarked that in that mild climate the usual heating apparatus was an iron or bronze pan for charcoal, such as is still in use in Italy, and that large houses were warmed by pipes of hot air, running under the floor, like our furnaces. The windows were small and high, and usually closed with wooden shutters. It was not an object with them to look at the street, or, if they ever wished to do this, they made use of balconies: the windows were only for light and air. About the time of the Empire, windows of mica came in use, and glass was also employed for this purpose, although not extensively; for cups, vases, etc., it was a common material, and was manufactured with great skill.

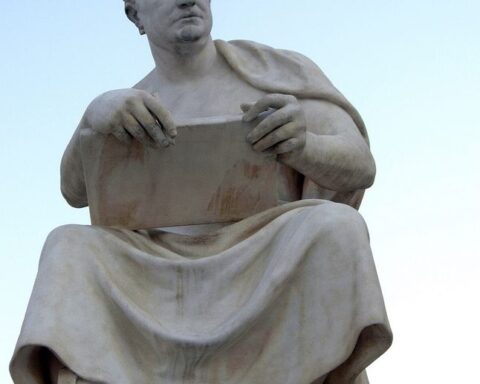

Again, take the dress. What is the Roman toga but the Indian blanket? somewhat altered in shape, to be sure, and worn in a peculiar and distinctive manner, but unmistakably inherited from that period when a single piece of woollen cloth was the sole garment. Indeed, even in the earlier years of the Roman Republic, we read of persons clad in the toga alone. Afterwards the tunic was introduced, a garment almost precisely like the sleeveless shirt, with a belt about the waist, which also served as a purse; and, until toward the close of the Republic, this, with the toga and a pair of shoes, formed the entire dress of a Roman gentleman. The toga was a large blanket of unbleached wool, approaching the shape of a semicircle, but broad in proportion to its length. One end was thrown from behind over the left shoulder, hanging down over the left arm, and reaching nearly to the feet; it was then brought round from behind under the right arm, the curving edge hanging nearly to the ground, and the other end thrown back over the left shoulder. The right arm was in this way left free, the left being quite covered. To wear the toga, and wear it in this formal and artificial manner, was the peculiar right of a Roman citizen; and great pains were taken by fops to make it hang gracefully, in folds prepared and pressed out over night. And not merely was it the exclusive right of a Roman citizen to wear this, but it was a breach of decorum for him to be dressed in any other way, when performing his duties as a citizen. The officer sent to announce to Cincinnatus his appointment as dictator found him ploughing in the field, nudus, or “naked,” meaning by this, perhaps, in the tunic alone. “Clothe yourself,” said the messenger, “that I may lay before you the commands of the Senate.” Then he directed his wife to bring his toga from the house, washed himself, put on the toga, and listened to the message. In later times the citizens were less scrupulous about this. It is related of the Emperor Augustus that, seeing one day in the assembly a crowd of people dressed in the pallium (a Greek garment), he repeated indignantly the words of Virgil, Romanos rerum dominos gentemque togatam (the Romans, lords of the earth, and the race that wears the toga), and ordered the ædiles thereafter to admit no one into the Forum or Circus without a toga — much as, in the Rome of the present day, no man is admitted to certain festivals without a dress coat. Again, Cicero, in his fiery invective against Mark Antony, contrasts the manner of his own entrance into the city with that of his enemy: “I came by daylight, not in the dark; in shoes and toga, not sandals and cloak” — the shoes and toga being the fit and becoming dress of a Roman Senator, while sandals and cloak were indications of foreign manners.

A clumsy garment like this, worn in so formal a style, might make an imposing appearance in the Senate, as it certainly gives dignity and grace to a statue; but it must have been sadly in the way when there was anything to be done, especially anything that required the use of both hands. In point of fact, it was purely a show garment, laid aside when there was any work to be done; in the army it was exchanged for a military cloak. Moreover, it was worn only by citizens; and the Roman citizens for the most part practiced no handicrafts — it was slaves, freedmen, and foreigners that carried on the petty trades and mechanical arts at Rome. The poor citizen — ignorant, needy, vicious, it might be — was entitled by virtue of his citizenship to live without labor. He received corn gratuitously, or for a nominal sum, from the State; he fastened himself upon some wealthy patron, and was fed by him; but work he would not. He was a Roman citizen — one of the lords of the earth. To attend the public assemblies and courts of justice, the gladiatorial shows, the theatres, the baths, and the games in the Circus — these were the lofty employments in which he passed his days, and to these the sweeping toga was no hindrance. But as soon as his duties as a citizen were over, or if he had any manual task to perform — and tilling the earth was always a respectable occupation, however despised the tradesman and mechanic might be — the Roman doffed his uncomfortable garments of state. When he entered his house, he exchanged his shoes for sandals or slippers, and put on an easy gown of any color to suit his taste. So in bad weather, or travelling, he wore a rough cloak and a hat.

De Quincey says, in one of his brilliant but overwrought descriptions: “The Roman was the idlest of men. ‘Man and boy’ he was ‘an idler in the land.’ He called himself and his pals ‘rerum dominos gentemque togatam,’ the gentry that wore the toga. Yes, and a pretty affair that ‘toga’ was. Just figure to yourself, reader, the picture of a hard-working man, with horny hands, like our hedgers, ditchers, weavers, porters, etc., setting to work on the highroad in that vast sweeping toga, filling with a strong gale like the mainsail of a frigate . . . . Had there been nothing left as a memorial of the Romans but that one relic, their immeasurable toga, we should have known that they were born and bred to idleness. In fact, except in war, the Roman never did any thing at all but sun himself . . . . The public ration at all times supported the poorest inhabitant of Rome, if he were a citizen. Hence it was that Hadrian was so astonished with the spectacle of Alexandria, ‘civitas opulenta, fæcunda, in qua nemo vivat otiosus’ (a rich, populous city, in which no one lives idle). Here first he saw the spectacle of a vast city, second only to Rome, where every man had something to do . . . . This prodigious spectacle (so it seemed to Hadrian) was exhibited in Alexandria, of all men earning their bread in the sweat of their brow. In Rome only (and at one time in some of the Grecian states) it was the very meaning of citizen that he should vote and be idle.”[2]

In this proud contempt for labor we see another illustration of the nearness of the Romans to barbarism; it is exactly the characteristic of savages.

The complete dress, then, of a Roman Senator was tunic, toga, and shoes — a marvellous contrast to the complicated suit that is worn by Mr. Gladstone or General Grant. But the less hardy generations of the Empire found this insufficient. Many, even, during the Republic, wore two tunics, and leggings reaching not quite to the knee — pantaloons were despised as a barbarian institution, and a mark of effeminacy. About the same time hats began to be more generally worn, and we are told that Augustus, simple and conservative as he was in his tastes and habits, always wore a hat in the sun to shield him from its rays. The dress of the women was originally the same as that of the men. But in course of time the stola was established as their distinctive garment an outer tunic reaching to the feet; over this a shawl (palla) instead of the toga, and generally sandals instead of shoes. If they wished to cover their heads, they used a shawl, or at most a hood, such as men also wore sometimes in bad weather. The wife of a Roman nobleman cost him nothing for bonnets!

The civil and political institutions of the ancients betray still more unequivocal marks of their nearness to barbarism, especially in the remarkable degree in which the primitive patriarchal institutions remained in force. Whatever might be the station or power attained by a Roman citizen in his public career, he was at home, so long as his father lived — and his wife and children as well — a slave of that father; nor could he himself become a paterfamilias, or head of a family, until his father’s death. Nay, more, not only did the father possess this authority, but it was out of his power to divest himself of it, except by the fictitious process of selling the son as a slave, with the understanding that the purchaser would manumit him. Even this did not make the young man free. He reverted again to his father’s authority; and, in order to make his emancipation complete, it was necessary to repeat this process three times. Then, thrice sold and thrice manumitted, he stood a free citizen, and a paterfamilias himself. This power extended even to life and death. A Roman magistrate — vast as his power was — dared not put a citizen to death without formal trial. Cicero himself never recovered from the obloquy that he incurred by venturing to punish with death the leaders in the conspiracy of Catiline without due form of law; and yet he was backed by all the authority of the Senate. But at that very time Aulus Fulvius, a man known to us by this one act alone, exercised, unchallenged, unrebuked, and irresponsibly, this power denied to the consul, by beheading his own son, in his own court-yard, by his own sole authority.

Another ancient custom, still more prevalent among the Greeks than the Romans, reveals the element of barbarism still more startlingly — the common and recognized practice of infanticide. When a child was born, it was for the father to say whether it should be reared or not. It was laid at his feet, and, if he lifted it up sustulit — this was interpreted as an expression of his willingness to undertake its support. In one of the comedies of Terence, an old bachelor, remonstrating with his married brother that he is too penurious toward his two sons, says, “You lifted them both up, knowing just what means you had, with the expectation that what you had would be enough for both of them.” If the father did not “lift up” the child, he was considered to have disowned it; and it was put to death, generally by being exposed in a forest and suffered to perish. An old law of Rome forbade exposing boys unless deformed, or the eldest daughter — with younger daughters the practice was common, for women were of little account in those times, as is illustrated by the fact that girls had no distinctive names. The sons were Marcus, Publius, Lucius, Titus; but their sisters had nothing but the family name: Cornelia, Lucretia, Licinia, numbered first, second, and so on, as many as there chanced to be.

Still, the Roman women were not wholly without honor. Their position was far superior to that of any other women of antiquity, both in the respect shown them and in the character by which they earned this respect. The typical Roman matron is a fitting mate of the typical Roman Senator; there is the same heroic, lofty spirit and intrepid bearing in her, too, as in him, not unmixed with the characteristic fierceness of the nation. Cicero mentions several women whose refined culture, especially in the use of the Latin language, was noted, and had exercised a powerful influence upon the male members of their family. And Roman history is illustrated by the names of women in whom strength of character was not inconsistent with the more womanly graces — from Cornelia, the mother of the Gracchi, to Arria, the wife of Pætus, who, when her husband hesitated to put himself to death at the command of the tyrant, herself plunged the dagger in her own bosom, and handed it to him with the words, “Pætus, it does not hurt.”

“When Arria from her wounded side

To Pætus gave the reeking steel,

‘I feel not what I’ve done,’ she cried,

‘What Pætus is to do I feel.’ “[3]

It may be that we do not habitually do justice to the family relations of the Romans; their sternness and fierceness overshadow their finer qualities. But family affections appear to have been very strong and tender, especially between brothers, as we see in Cicero’s correspondence with his brother Quintus. The marriage relation was also, with the best Romans, a very happy one. And here is a striking and noteworthy fact. There is throughout ancient literature hardly a trace of the passion which we call peculiarly “love.” Marriage was a concern managed entirely by the parents, who exercised the power, as they had the right, to betroth son or daughter as they pleased. The young lady lived a very retired, secluded life indoors, hardly seeing any male acquaintances; and as for falling in love, forming an attachment which should result in marriage, the thought hardly occurred to her. But although the marriage relation was thus entered into, not from personal inclination, but from a sense of duty, with no people has it been held more sacred, and have there been more shining examples of a true and happy union, than among the Romans of the Republic. The reason was that a religious sense of duty governed both husband and wife. There was no nonsense of elective affinities, and spiritual attraction, and uncongeniality of temper, to destroy harmony and happiness; but both parties to a contract not made by themselves, but which they deemed an irrevocable one, felt themselves bound by every consideration of manly honor and womanly devotion to do their full duty in the position in which the gods had placed them. Until luxury and corruption had crept in and undermined the very foundations of morality, this was the nature of wedlock — the strong foundation on which the Roman family rested; and even through all the debauchery and degeneracy of the Empire we never fail, now and then, to catch a sight of beautiful examples of genuine Roman manhood and womanhood united in a marriage bond as holy and indissoluble as in the palmiest days of the Republic.

It may perhaps be of interest at this point to copy the inscription upon the sepulchre of a Roman matron — it is the stone which speaks: —

“Brief, traveller, is my message — pause and read it.

The poor stone covers a beautiful woman.

Her parents named her Claudia:

With single love she loved her one husband;

Two sons she bore — one she left behind her on earth,

The other she buried in the bosom of the earth.

She was becoming in speech and noble in mien;

Cared well for her household, and span. I am finished — Go.”

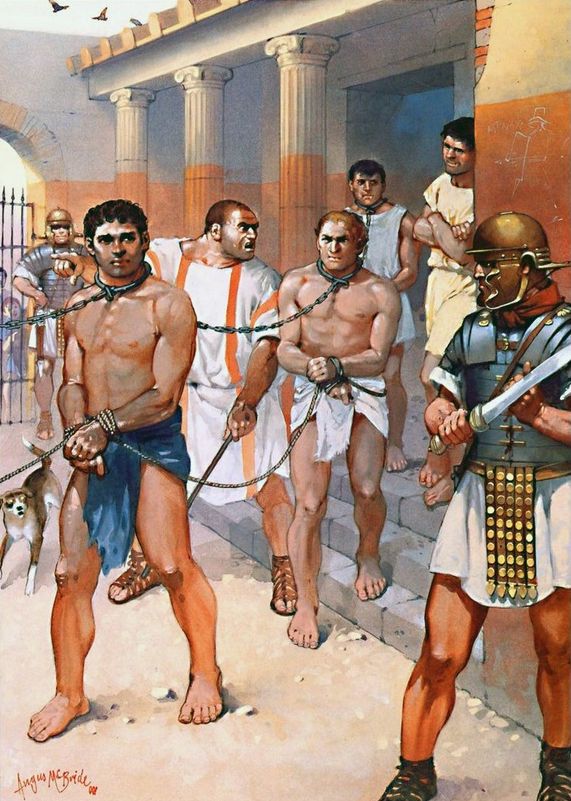

Another feature of family life remains to be mentioned: the slaves, so important a portion of the Roman household as to be called peculiarly “the family.” American slavery gives no adequate idea of Roman slavery. The slaves in this country were of a different race and a different color, vastly inferior to their masters in ability and education. In Rome, on the other hand, by the side of natives of various barbarous tribes, who were employed only in the rudest branches of industry (a class which corresponds in character and position to the American slaves) by the side of these there were slaves brought from all the most polished nations of the world — Greeks, Egyptians, Syrians, Asiatics and their functions in the household were commensurate with their talents and attainments. The steward of the estate, the tutor of the children, the librarian, the secretary — all were slaves. A wealthy Roman possessed troops of slaves of all kinds — it was his pride not to be obliged to go beyond his own farms and his own “family” to supply all his wants. But in nothing was the native barbarity of the Romans more glaringly exhibited than in their treatment of these unfortunates. The vindictive excesses of passion which are related as the rare exceptions in the treatment of the negroes of the South were every-day affairs with the Romans. If the life of the Roman citizen could not be touched, that of the slave was cheap enough. Nor was the brutal passion of the master satisfied with killing — it must be death by torture — by the cross or it might be by being thrown into the fish-pond to fatten the lampreys. After a servile insurrection in Sicily, twenty thousand slaves in that one island were crucified along the highways.

The horrors of Roman slavery — more terrible than it is easy for us to conceive of — were, however, somewhat mitigated by the commonness of emancipation. The freedmen, or emancipated slaves, were so numerous as to form a class by themselves, and a very important one. But although free, and thus no longer exposed to the grossest abuses of slavery, the freedman still remained in a relation of dependence upon his former master, and was known not merely as freedman (libertinus), but as his freedman (libertus). His relation to his patron did not differ materially from that of the client, only that he was considered bound to perform for him whatever services were in his power, almost as when he was a slave. Nothing is more common than to meet with accounts of freedmen who acted as the confidential servants or agents of their patrons; and this, it would seem, without any regular remuneration, except their favor and patronage, and the hope of a legacy. The slave gained by his emancipation, therefore, principally the right to own property and the exemption from abuse, not the freedom from the obligation to service.

It has been said that the freedmen were practically on the footing of clients. Every poorer man in Rome found it necessary to attach himself to some one of the nobles as his protector, and, so to speak, his representative. Rome was through and through an aristocratic State. The idea of equal rights for all would have been a strange one in those days. It was only through the favor and assistance of some powerful noble that any inferior citizen could hope for redress in any grievance, or justice in any suit. Every nobleman was by virtue of his position a lawyer, as well as a statesman and a soldier; and it was his duty to protect his clients, to defend them in any case at law, and to act for them in all important affairs. Both parties were benefited by this; for the noble derived much of his dignity and influence from the number of his clients.

Having thus given a general outline of the Roman household and its members — the paterfamilias, the wife, the children, the slaves, freedmen, and clients — let us take up the history of a single day, to see how this family lived. Two or three ancient writers have given us detailed accounts of the manner in which the day was spent; the briefest of these, and the best fitted for our purpose, is contained in an epigram of Martial, a popular poet, who lived about a century after Christ. It should be premised that the Romans divided the day, from sunrise to sunset, into twelve equal hours, varying, therefore, in length at the different seasons of the year.

“Two hours the clients crowd your stately halls;

The third the lawyers bellow themselves hoarse.

Work till the fifth, the sixth for quiet calls,

Then through the seventh all business runs its course.

The eighth hour baths and exercise you need;

The ninth hour spread your table; and your friends

Listen, the tenth, while you my verses read,—

What were a feast unless the Muse attends?”

We will now follow out this programme hour by hour. Let us personify our account, and call our nobleman by the aristocratic name of Paullus Æmilius.

The Roman rises early — commonly by daybreak. It does not take him long to make his toilet.[4] The bathing and shaving come in the afternoon; and there are no strings or buttons to fasten, no collar to put on, no cravat to tie, no waistcoat, pantaloons, stockings or underclothes, no watch or pocket-knife, no hat or gloves. He slips himself easily into his tunic, and fastens around his waist a belt which has a money-pouch attached to it. A slave ties his shoes and folds his toga gracefully about him, and he steps from his bedroom into the atrium, already crowded with eager and obsequious visitors. Here is a tenant of one of his farms, come to pay his rent; here a freedman in attendance, to see if his patron has any commands for him; here is the steward of his villa, with his monthly report; here is a yeoman who owns a small piece of land near his villa, and has attached himself to his wealthy neighbor as a client — he comes bringing a gift of a fat capon, and tells a story of some outrage committed by the bailiff of another nobleman, and begs for protection; here is a city client, who is involved in a suit at law, and comes to consult Æmilius; here is a crowd of needy parasites, whose whole living is derived from the daily allowance given them by their patrons; they present themselves at more than one hall every morning, and the bargain is reckoned a fair one — the consideration and distinction derived from a numerous body of clients, and their votes when the patron is a candidate for any office, are well worth the trifling cost of their gratuities. In attending upon these visitors an hour or two passes. An educated slave no doubt attends his master to take notes, if necessary.

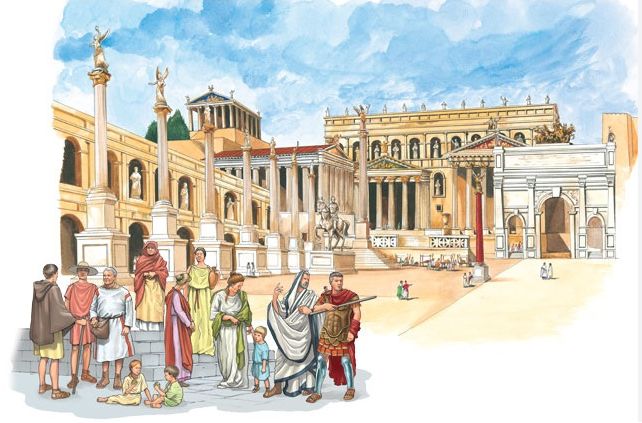

The morning salutation being over, Æmilius partakes of a slight breakfast of bread and figs or olives— alas! the Romans knew not coffee, nor buckwheat cakes, nor waffles, nor rolls and butter. If the morning was chilly, and they wished a warm breakfast, there was the favorite calda, wine mixed with hot water, probably spiced, and sweetened, if at all, with honey — for sugar they had not. After this frugal breakfast, Æmilius betakes himself to the Forum, or market-place, to attend to the business of the day. Every town or city of the ancients — like every European town of the present day — had its open square, or marketplace (forum), as the centre of all business, public and private. Around this, or in its neighborhood, were the most important temples and other public buildings. Here courts of justice and public assemblies were held, originally in the open air. The public assemblies, indeed, were always held in the open air. The courts of justice sat in later time in the Basilica, an open hall, used also by the merchants as an exchange. Æmilius, therefore, proceeds to the Senate, if the Senate is in session to-day — for, being a permanent body, all its members residing in Rome, it sits only when there is business to be transacted; if there is no Senate, to the Basilica which his father had erected, to attend the trial of a case in which he is interested; or, if there is a public assembly, to the Forum, to hear Pollio or Messala address the people; or, if there is neither Senate assembly nor court, he attends to his own private concerns, lounges in the Basilica or on the Forum, and talks with his friends on the news from Parthia or Spain, or on the prospect of an outbreak between the triumvirs, Mark Antony and Octavianus.

In this way the hours of the forenoon pass, and at noon, or soon after, the business of the day is over. All this time, the narrow, crooked streets, lined with high, irregular houses, abutting directly upon the street, with no sidewalks, have been the scene of the extremest bustle and confusion, with the dealers in various commodities carrying about and proclaiming their wares. Carts, too, are allowed in the city during the morning hours for purposes of trade; but carriages are never permitted there, except to ladies or on rare festal occasions. Whoever does not wish to walk must be carried in a litter or ride horseback. The hurry, bustle, and confusion of the streets of Rome are frequently mentioned by ancient writers, and probably the streets of modern Cairo or Constantinople give a fair notion of them.

At noon, therefore, we have a cessation of business, which is not resumed unless there is some special occasion. The second meal, prandium, is now taken, which appears to have been much the same as the first, only somewhat heartier, often with some meat or fish. Like the first, it might be taken wherever a person happened to be, generally with no formality. Frequently no table was set at all, and sometimes it was entirely omitted. It is therefore incorrect to call the prandium “dinner,” which is, as De Quincey urges, “the principal meal of the day, the meal upon which is thrown the onus of the day’s support.” Let us call it luncheon.

How, meanwhile, has the wife of Æmilius, the matron Cornelia, passed her forenoon? It is hard to say. The life of women in no age or country admits much variety, least of all that of virtuous women among the ancients. As a lady of the old Roman stamp, she has employed herself, no doubt, in superintending the labor of her slaves: the rooms were to be cleaned, the floors swept and polished, preparations to be made for the evening’s festival. If she does not spin and weave with her own hands, like her ancestors, she has been fully occupied in overseeing her slaves that did. For there were no Lowells and Manchesters in those days: all the noblemen’s articles of clothing were made here in his own house. This huge pile of wool came from the backs of his own sheep, on his Apulian pastures. On this loom you see a toga near its completion — woven in one piece, heavy and fine, with a soft nap like velvet — already narrowed towards the end, to show its rounded form. On this other is a piece of cloth to be made into a tunic. A broad stripe is woven in it, of wool dyed in the costly Tyrian purple, intended to run up and down in front of the garment, marking Æmilius as a Senator: this is the latus clavus. In this other room is a company of slaves making up garments, either for their master’s use or coarser ones for themselves. In these employments Cornelia finds that the morning does not drag upon her hands; and while her two boys, Lucius. and Marcus, are at their school, reading Homer or writing rhetorical exercises in Latin, her daughter Æmilia [Emily] accompanies her mother in her labors, gives her what aid she can, and learns how to manage a household, in order that, when married to the young Licinius, to whom her parents betrothed her the other day, his house may be cared for in a manner worthy a Roman nobleman.

But let us turn for a moment from our chaste and virtuous Cornelia, a Roman matron of the old stamp, and read the description which Lucian gives of the fashionable ladies two centuries later: —

“If any one should behold these ladies at the moment that they wake in the morning, he would certainly believe he saw a monkey or a baboon, to meet either of which on going out in the morning we are accustomed to consider a bad omen. For this reason they shut themselves up so closely at this time that no man’s eye can see them …. She is at once surrounded by a circle of officious nurses and attendants, who make it their business to revive upon her countenance its faded beauties. To wash the sleep out of her eyes with fresh spring water, and then betake herself briskly and cheerfully to her household duties — what an absurd and old-fashioned notion! No, there must first be all sorts of ointments, powders, and essences. The performance has quite the look of a public display. Each maid and attendant has a special part of the toilet to attend to. One brings a silver washbasin, another a pitcher, others mirrors and casketsboxes enough to make up the stock of an apothecary. And in none of them is there anything but falsehood and deception — in one teeth and coloring for the gums, in another black eyelashes and eyebrows, and other tricks of the toilet. But the greatest art and the greatest time are spent upon the hair. Some, who have the madness to change their natural black hair into blonde or golden, color it with ointment, which they then suffer to dry in the sun at mid-day in order to set the color. Others, who are content to wear their hair black, spend their husbands’ entire income upon it, and let all Arabia Felix[5] breathe from their locks.”

Not so very different from some fine ladies of a later day, even to the dyeing of the hair yellow — a custom which the Roman ladies adopted in admiration of the northern nations, which they had just come to know. Nor was false hair uncommon : one of their poets writes: —

“The golden hair that Livia wears

Is hers — who would have thought it?

She swears ’tis hers, and true she swears;

For I — know where she bought it.”

But what does Lucian mean by the unsavory comparison with the baboon? Why, this: that the favorite method of the ladies of his day, to preserve their complexions, was to bathe their faces on going to bed in a gruel made of bread and asses’ milk. This became hard, dry, and discolored during the night, and the first process in the morning was to wash it away with warm asses’ milk — the Empress Poppea was always, in traveling, accompanied with troops of asses, stated at five hundred in number, to provide her with her indispensable baths. This yesterday’s rubbish cleared away, a slave touches up the cheeks artistically with white and red paint, and another shades the eyebrows and eyelashes with a black powder — and the fair face is finished.

It is afternoon now. The prandium is over, and the siesta too, if any have indulged themselves in that luxury. No more labor to-day, unless to hard-worked slaves or to lawyers or magistrates whose business will not wait. It is afternoon, and all Rome is taking holiday. What occupation does Martial’s epigram give for the afternoon? “Baths and palæstra.” But Martial lived in the time of Trajan, and our Æmilius in that of Augustus. Under the Empire, the daily bath was the grand object of life with the enervated, luxurious Romans; and the thermæ, or warm baths, were among the most magnificent of the structures of the city. There were several of these, built at different times, the largest perhaps a third of a mile square, fitted up with every variety of luxurious baths and provided with pleasant grassy lawns, with halls for games and gymnastic exercises, with porticos and lecture-rooms for conversation or instruction. To these the people were admitted, either gratis or for a mere nominal sum; and here they spent hours of every day. We may praise the Romans for their cleanly habits; but cleanliness ceased to be the object — it was the mere sensual gratification, derived from the succession of the different kinds of baths in which an idle and dissolute people wasted their hours.

But Æmilius has no such establishments as these to visit; nor is he a mere trifler, to spend the whole afternoon in soaking and scraping himself. Indeed, these establishments were not intended for the rich and aristocratic, who in those days had elaborate bathing accommodations in their own houses, but chiefly for the mass of the citizens, to whom this was a part of the price paid by the emperors for the privilege of ruling. At the close of the Republic there were no free baths on this magnificent scale. Therefore, if Æmilius has no rooms in his own house set apart for this purpose, he is satisfied to go, as his ancestors did, to a barber’s shop and have his beard shaved, his hair cut, and his nails trimmed (a thing no gentleman thought of doing for himself); then to one of the balneæ, or private bathing establishments, where he takes such a simple bath as suits his tastes.

We may fancy him then, now that the business of the day is over, spending the rest of the afternoon in any way that we fancy. Perhaps he orders his carriage to wait him at the Porta Capena, and he himself rides on horseback, while his wife is carried in a litter to the gate; they mount the carriage, and, driven by a slave — for no Roman gentleman may lower himself by holding the reins — enjoy an afternoon drive over the Campagna, while the declining sun lights up the Sabine mountains with a brilliant purple, and the Alban hill lies in sombre shadow. Perhaps they go along the Appian Way, crowded with travel and traffic, and lined with splendid tombs on both sides; if this is not retired enough, towards Ostia, to get a whiff of the sea air; or to visit a friend’s country seat in Etruria, or inspect their own villa at Tusculum. Or perhaps he may prefer to recline in his own parlor, and have a slave read to him a new satire of Horace, or an historical treatise of Varro, or one of Cicero’s never tiring speeches.

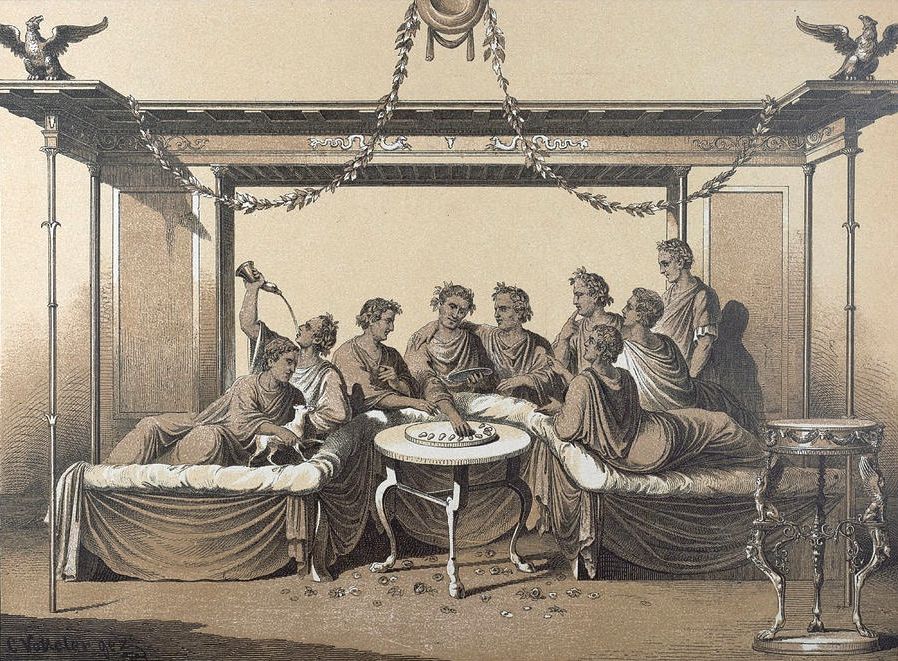

At length it is the dinner-hour, and the guests begin to arrive — a party of gentlemen, all high-born and wealthy, all rejoicing at the prospect of an outbreak between Antony and Octavianus, and some venturing to hope that the result will be a restoration of the commonwealth. On ordinary occasions, Æmilius dines with his wife and children — it is the only family meal. Civilization has not so far conquered the habits of barbarous life as to bring the whole family together to the morning and mid-day meal. These are still solitary, informal, individual, occasional; but towards evening civilization conquers at last, and, when the work of the day is all finished, brings the whole family to a common table. In olden times they sat at table; but the later Roman felt himself disinclined for so much exertion, and reclined on a broad couch, leaning on his left elbow, and feeding himself with his hand from the bits of food cut up for him by the slaves in attendance. Forks were unknown — knives were hardly used at the table — spoons, pointed perhaps at one end, were the only implements, except their fingers, which were made before forks; and was it not an easier and more lordly thing to be spared the trouble of cutting at all, and use the fingers, with a slave at hand to wash them with perfumed water? Women, however — was it modesty or dignity or self-sacrifice, or was it that the lords of creation ruled it so? — women did not recline at meals, but still sat, as their ancestors did.

To-day, however, is a banqueting day. Æmilius receives his friends in his splendid triclinium, or banqueting hall, while Cornelia dines in the common room of the family, with her daughter, the gentle Æmilia, and the two schoolboys Æmilii; and let us trust that they behave better than boys are apt to do nowadays when left thus, not forgetting that they are destined one day to be Senators and Consuls.

The great banqueting hall contains three broad couches, placed to form three sides of a hollow square, each calculated to accommodate three guests. Varro, the great antiquarian and scholar, has declared that the number of guests should never be less than that of the Graces (three) nor more than that of the Muses (nine); a dictum which has come down to our days, as a rule which everybody respects, but nobody obeys. But at a Roman dinner the accommodations of table and couches limited the number to nine. We will close the door upon Æmilius’s banquet — its political conversation must be kept a secret. In its place, we will copy from a Roman novel — the Satyricon of Petronius[6] — the description of a dinner, given by one of the guests :—

“For the first course, we had a hog crowned with pudding, and garnished with fritters and giblets, capitally dressed; and there was endive and bread of whole meal, which I like better than white. For the next course we had excellent cold tarts with Spanish honey poured warm over them. So I ate no small share of the tarts, and smeared myself well with honey. All round these, chickpeas and lupines, nuts in plenty, and an apple apiece. I, however, brought away two, and here they are tied up in my napkin; for, if I carry home nothing to my favorite slave, I get abuse. Ha! true, my wife reminds me, had on a side table a piece of bear’s ham, and I ate more than a pound of it, for it tasted quite like boar; and, said I, if bears eat a man, with how much more reason may men eat bears! Finally, we had cream cheese, grape jelly, a snail apiece, chitterlings, livers in pâté-pans, chapcrowned eggs, turnips and mustard, and a dish of kidney beans. There was also handed round a wooden bowl full of salted olives, whence some of the party unfairly helped themselves to fistfuls.”

A brief account, from Suetonius, of the personal habits of the Emperor Augustus, one of the most finished gentlemen of antiquity, will fitly conclude this attempt to illustrate the daily manners of his countrymen:

“His economy in furniture and household utensils can be seen even now [one hundred years later] from the beds and tables which are still in existence, many of which are hardly elegant enough for a private gentleman. They say he never slept on any but an ordinary bed, and with bedclothes of a common sort. He did not often wear any but home-made clothes, made by his sister, wife, daughter, and nieces. His toga was neither sweeping nor scanty in dimensions; his purple stripe neither broad nor narrow; rather high shoes, so that he might look taller than he was. And he never failed to have his outdoor clothes and shoes in his bedroom, ready for any sudden and unexpected need. He banqueted frequently, but never except in regular form, nor without careful selection of his companions. … His dinner consisted of three courses, and never, when most sumptuous, of more than six; but, although he was thus economical, it was always of consummate elegance. For, if the guests were silent or conversed in a low tone, he would challenge them to a general conversation; and he enlivened the feast with singers and stage-players, or even with pantomimists from the Circus, and quite often with buffoons. Feast days and anniversaries he celebrated with great magnificence. . . . The food that he ate himself was small in quantity and of an ordinary quality. Stale bread and small fishes, and fresh cheese of cow’s milk, and green figs were what he was most fond of. The earlier meals of the day, before the dinner, he took wherever he happened to be. These are his own words from a letter. We lunched in the carriage, on bread and dates.’ Again, ‘On my way home from the Regia, I ate an ounce of bread, with a few grapes.’ And again: ‘No Jew, my Tiberius, fasts more rigidly on the Sabbath than I have done to-day, for not until after the first hour of the night [at about 6 P.M.] did I eat a couple of mouthfuls in the bath, before I was rubbed with oil.’ From this carelessness it resulted that sometimes he dined alone, either before or after the banquet, taking nothing at the table. He was likewise very temperate in the use of wine . . . Instead of drinks, he took bread soaked in cold water, or a slice of cucumber, or a head of lettuce, or a fresh sour apple of winy flavor. After luncheon, when he had dressed and put on his shoes, he took a short nap, holding his hand before his eyes. After dinner he went at once to his study. There he remained until late at night, making out either wholly or chiefly the records of the day. Then, going to bed, he slept not more, at the outside, than seven hours, and that not continuously, but waking three or four times in the interval. If he could not get to sleep again, as sometimes happened, he called a reader or story-teller, and worked often until after daylight. . . . In winter he wore fur tunics, with a thick toga, with an undervest fitting close to his body; his legs and thighs were also covered. In summer he slept with open doors. . . . He could not bear the sun, even in winter, and never walked in the open air without a hat. . . . He gave up field exercises of arms and on horseback immediately after the civil wars, and took instead to playing ball; afterwards he rode in a litter and walked, wrapped in a blanket, leaping at the end of the walk.”

The Paullus Æmilius whose day we have endeavored to reconstruct from fancy is no fictitious character. He was a nephew of the triumvir Lepidus, and was consul in the year thirty-four before Christ. Very little is known of his history, and it may be he did not deserve the character we have ascribed to him, of a Roman of the old type; but one would not willingly believe that it was a mean or wicked man to whom were addressed the tender verses of Propertius, in the name of his deceased wife:

“Cease, Paullus, to entreat my grave with tears

The black gate opens to no human prayer.

When once the shade in Pluto’s halls appears,

The road is ever closed that brought it there.

. . . . . . . . .

“Now to thy care the pledges of our love,

Even from my ashes, fondly I commend.

The father now a mother, too, must prove,—

Let my caresses in thy kisses blend.

Be cheerful, if thou canst, when they are by:

Alone and in thy chamber mourn for me;

And if thou seest my form, and deem’st me nigh,

Believe that she thou lov’st will answer thee.”

____________________________________

[1] shave: to discount (a note) at an exorbitant rate. (Merriam-Webster) [ed.]

[2] Two or three inaccuracies in this extract may be noticed. The hard-handed farmer did wear the toga, but of course not when working on the highway. Again, it was not until late in the Republic that corn was distributed to the people, and even then only at a reduced rate at first, and not enough at that to support a family without labor.

[3] Martial, Hoadley’s translation.

[4] dress and groom himself [ed.]

[5] Yemen, famed for its spice trade in Roman times. [ed.]

[6] Bohn’s translation.

That was fascinating. I had come here after reading something by Iain Calderwood on paintings depicting Greek mythology, searching for things on Pocris and depictions of marital relations in general at the time. I was a bit amazed at what I thought was a very shallow observation of paintings in the British Museum he is some sort of curator for. He should read articles such as this to get a fuller appreciation of ancient Greek and Roman life. Thank you.