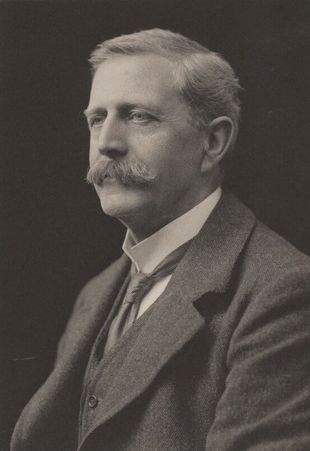

Editor’s note: The following (original title, “Napoleon”) is extracted from Historical Vignettes, by Bernard Capes (published 1910).

It was the fourth of July, 1809, and thunderous, close evening. In Lobau, the largest of the five islands on the Danube, where were the imperial headquarters, the huge machinery of war, human and insentient, was getting up steam, so to speak, for the morrow’s milling, and eliciting, as its flywheel slowly revolved, an automatic response in all its myriad parts from Pressburg to Vienna. The occasion, it might be said, was an emergency occasion. If the Emperor, himself commanding, had not been thrashed by the Austrians, under the Archduke Charles, a couple of months earlier at Aspern, his retreat upon the islands had looked so much like a defeat, that for the moment his supremacy, moral and material, hung in the balance. For the first time the Grand Army had suffered a shock to its amour-propre[1] and its hitherto invincible faith in its leader. A little might turn the scale, and send all its disintegrated legions scuttling back to Strasburg.

That the impenetrable “Antichrist” himself was fully aware of the nature of the hazard there is no reason to doubt, or that he was concentrating all the deepest faculties of his genius on the delivery of a blow which should be immense and final. He was much alone in his tent, and his orders were laconic and momentous. The ordinary mind cannot picture such a situation, and dismiss its surrounding distractions—one might say its hauntings. There were the arsenals, the forges, the rope walks, the sheds for boat-mending, the canteens and parks of artillery all over the five islands; there were the boats themselves in the river, scores of them, and the massive chains which bound them into bridges; there were the ammunition wagons and their loaded boxes, the forests of piled arms, the tossed oceans of tents, the miles of tethered horses, the ring-fences of palisades; and there were the troops for last, enough to people a great city, and each man of them as cheerily busy as if he were one of an exodus of Israelites picketing on his way to the promised land. Seven weeks before this same island of Lobau had been littered with the legs and arms of those wounded at Aspern—limbs hastily severed and flung helter-skelter among the grass of its meadows. Its soil was soaked with blood; thousands of mangled men and horses had sunk screaming in the waters which thundered by its shores; a hail of iron had smashed into it and its even more luckless neighbours; fire from burning mills had roared down upon its bridges, melting men and metal into one horrible annealing; it had heaved and vomited with the filth of war. And had all that hideous picture a place in the background of the master-mind, or had its present aspect, of busy preparation for another scene as sickening, or worse? One sorrow may have haunted him, one bloody ghost out of all the multitudes—the figure of his old comrade Marshal Lannes, as he had seen him borne hither on a litter of branches and muskets on the fatal day—one shattered horror more to feed the carnage. He had been moved a moment, had wept, and kissed the dying man. An unconscious thought of him may have lingered still like a melancholy shadow in his soul. But, for the rest, one may be sure that he looked over and beyond all these things, as a great architect sees through the maze of scaffolding the glory of the fabric his soul has raised. This man, it is to be supposed, ever regarded a battlefield but as a map, so clear to his mind, that, as the opposing troops manœuvred on it, he could check or reinforce them, show them the way to defeat or victory with his eyes shut. He was a calculating “freak,” and as such superhuman—or superdiabolic.

As the dark gathered, lit only by the flickering lightnings, an immense hush fell over the islands. Every lamp and fire was extinguished; the multitudinous tramp of moving hosts mingled with the boom of the river, and became part with it; the song of the bugles, soft and short, mounted on the wind, and fled with its shrilling through the branches of the trees. One might never have guessed the universal movement that was taking itself cover, as it were, under these silences, as if the islands themselves had been unmoored, and were drifting soundlessly, with their freight of death, towards the shores.

In the midst, a little cry, sharp and sudden, rang out in the neighbourhood of the Emperor’s tent—it might have been a trodden bird’s; it passed, and was not repeated. A young officer, de Sainte Croix, of the personal staff, hurried towards the spot. It was he, vigorous and enthusiastic, who had often gained the Emperor’s approval by climbing tall trees on the island to watch the Austrian preparations on the distant plain. He found a sentry standing by a clump of bushes, and another, one of the Old Guard, lying prone at his feet.

“Malediction!” he whispered. “Who had the daring?”

The man saluted.

“It is Corporal Lebrun, Monsieur. He gave one cry—thus; and I saw him fall. He was hit over the heart at Essling, and only his cartouchier[2] saved him; but he has complained since of an oppression. I think the closeness, the thunder—”

The officer interrupted him:

“That will do. You had no right to leave your post. Return to it.”

The soldier saluted again, wheeled, and retreated. De Sainte Croix bent over the fallen man.

“How is it, Lebrun?”

The corporal lay with a ghastly face, his breath labouring, his chest lifting in spasms. He was not a young man, yet prematurely aged, toughened, grizzled, tanned like old leather in the service of his god. There was a wild, lost look in his eyes which betokened the coming end. He struggled to speak.

“Lift me up, monsieur, in God’s name!” De Sainte Croix took the livid head on his knee. The posture somewhat eased the fighting heart.

“Courage, comrade! This fit will pass with the oppression. Why, I myself feel it—I. When the storm breaks—”

The blue lips caught at the word.

“When the storm breaks! What will he have answered?”

“He? Who?” said the young officer.

The dying corporal, twisting in his arms, made an awful gesture towards the Emperor’s tent.

“As always,” said de Sainte Croix, “with the cry to victory.”

The other clutched his hand with a grip like madness.

“I believe it, monsieur. He will have renewed the compact.”

“What compact, my poor friend?”

“With the red man.”

De Sainte Croix could hardly catch the answer.

He laughed—men must laugh, though they died for it—and spoke a soothing word. He believed the poor fellow delirious.

“I have laughed too, I have scorned, I have feigned to disbelieve,” said Lebrun, thickly and passionately. “I laugh no longer. Marengo, Hohenlinden, Jena, Austerlitz—what mortal brain unassisted could have so added victory to victory, could so, and for so long a time, have held the world’s destinies in the hollow of one hand? I am a soldier, monsieur, a simple, uneducated man, and yet I know things and I have seen things that would make the wise falter in their wisdom.”

“This red man, amongst others,” said the young officer conciliatingly.

A quiver of lightning at the moment glazed the dying face. Great drops stood on it; the fallen cheeks were filling with shadow; the eyeballs shone like porcelain. In spite of himself, a shiver ran down de Sainte Croix’s spine. There was certainly something uncanny in the night, even to war-toughened nerves. Lebrun’s voice had sunk to a whisper as he answered:

“Didst thou never hear of the General’s proclamation in Egypt to the Ulemas and Shereefs? He stood then on shifting sand—the English sea-captain had just beaten us. A false step, and he were engulfed for ever. And, to gain the people, he told them that their God had sent him to destroy the enemies of Islam and to trample on the cross.”

“Policy, Lebrun,” said de Sainte Croix, lifting his hand to wipe his own wet forehead. “He never meant it.”

“Then why, monsieur, did this blasphemy follow immediately on the visit of the red man? There had been no hint of it before and afterwards he swore to them that their false bible was the true word.”

De Sainte Croix snapped somewhat fretfully:

“This red man? Who the devil is he?”

A shudder quite convulsed the corporal.

“Thou hast spoken it, monsieur.”

“A figment of your excited fancy, soldier.”

“With these eyes I saw him, monsieur. It was ten years ago. I was on guard in a corridor of the palace at Cairo, and there came out of the General’s cabinet one who had never gone in. Little he was, like a child of a hundred years, and he had on a blood-red bernous,[3] and his face was black as a Nubian’s. Only at the lips it pulsed with fire, and fire, dim and wavering, travelled under his cheeks. One moment thus he stood—I could have touched him—and, behold! he was a little draped black figure of bronze that stood on a pedestal by a red curtain. It had always been there—I rubbed my eyes—”

“Voilà la chose!”[4]

“Monsieur, I dared. I listened at the General’s door, and I heard him laugh softly to himself—he who never laughs—and he said: ‘Greet thee, Zamiel! Ten years I have given thee to make me a god, or our compact is ended!’ Monsieur, the ten years are passed, and to-night he stands again, as he stood then, at the parting of the ways.”

A flash, more brilliant than any that had yet shown, weltered and was gone. The dying soldier lifted his head quickly, with a fearful cry:

“Ne savoir à quel saint se vouer![5] I saw him again—but now, before I fell, I saw the red man again, and he passed into the Emperor’s tent!”

The thunder followed on his word, with a rolling slam that shook the island.

“Lebrun!” cried the young officer. “Lebrun!”

The head was like a stone in his hands; he peered down sickly; the soul of the corporal had been shaken out of him with the crash.

And, even as de Sainte Croix rose, the storm broke, and under cover of it, and of the tearing wind and rain, began the first of those silent movements which were to precipitate the gathered hosts of the French upon the opposite shore—and victory.

A moment later the young man was back at his post, amid a shadowy flurry of equerries and staff officers. All seemed confusion, but it was the kaleidoscopic agitation which falls into place and order. As he stood, the enemy’s guns, startled into action, flashed deep and melancholy from the distant blackness, their roar mingling with the thunder’s.

It was in an instant of quivering light that, looking down, he was aware of something strange and red standing by his side. It might have been a child, a dwarf, a cuirassier’s scarlet cloak, grotesquely alive. In the momentary blinding darkness which followed it was lost to him. He heard, as his eyes recovered their focus, a measured voice speaking close by:

“I think we have them, M. de Sainte Croix, since I have resolved to renew my compact with Destiny.”

He started violently, saluted instinctively. It was the Emperor himself.

“By God’s favour, sire,” he said.

“Precisely,” said the Emperor dryly, and walked away.

____________________________________________

[1] Sense of self-respect.

[2] Cartridge belt.

[3] A hooded cloak.

[4] “There’s the thing,” i.e., “Then all you really saw was the little bronze figure.”

[5] “Not knowing which saint to turn to,” fig., “I was at my wits’ end.”