Editor’s Note: The following account is taken from Historical Tales, by Charles Morris (published 1896).

“In the year of our Lord 1307,” writes an ancient chronicler, “there dwelt a pious countryman in Unterwald beyond the Kernwald, whose name was Henry of Melchthal, a wise, prudent, honest man, well to do and in good esteem among his country-folk, moreover, a firm supporter of the liberties of his country and of its adhesion to the Holy Roman Empire, on which account Beringer von Landenberg, the governor over the whole of Unterwald, was his enemy. This Melchthaler had some very fine oxen, and on account of some trifling misdemeanor committed by his son, Arnold of Melchthal, the governor sent his servant to seize the finest pair of oxen by way of punishment, and in case old Henry of Melchthal said anything against it, he was to say that it was the governor’s opinion that the peasants should draw the plough themselves. The servant fulfilled his lord’s commands. But as he unharnessed the oxen, Arnold, the son of the countryman, fell into a rage, and striking him with a stick on the hand, broke one of his fingers. Upon this Arnold fled, for fear of his life, up the country towards Uri, where he kept himself long secret in the country where Conrad of Baumgarten from Altzelen lay hid for having killed the governor of Wolfenschiess, who had insulted his wife, with a blow of his axe. The servant, meanwhile, complained to his lord, by whose order old Melchthal’s eyes were torn out. This tyrannical action rendered the governor highly unpopular, and Arnold, on learning how his good father had been treated, laid his wrongs secretly before trusty people in Uri, and awaited a fit opportunity for avenging his father’s misfortune.”

Such was the prologue to the tragic events which we have now to tell, events whose outcome was the freedom of Switzerland and the formation of that vigorous Swiss confederacy which has maintained itself until the present day in the midst of the powerful and warlike nations which have surrounded it. The prologue given, we must proceed with the main scenes of the drama, which quickly followed.

As the story goes, Arnold allied himself with two other patriots, Werner Stauffacher and Walter Fürst, bold and earnest men, the three meeting regularly at night to talk over the wrongs of their country and consider how best to right them. Of the first named of these men we are told that he was stirred to rebellion by the tyranny of Gessler, governor of Uri, a man who forms one of the leading characters of our drama. The rule of Gessler extended over the country of Schwyz, where in the town of Steinen, in a handsome house, lived Werner Stauffacher. As the governor passed one day through this town he was pleasantly greeted by Werner, who was standing before his door.

“To whom does this house belong?” asked Gessler.

Werner, fearing that some evil purpose lay behind this question, cautiously replied, “My lord, the house belongs to my sovereign lord the king, and is your and my fief.”

“I will not allow peasants to build houses without my consent,” returned Gessler, angered at this shrewd reply, “or to live in freedom as if they were their own masters. I will teach you better than to resist my authority.”

So saying, he rode on, leaving Werner greatly disturbed by his threatening words. He returned into his house with heavy brow and such evidence of discomposure that his wife eagerly questioned him. Learning what the governor had said, the good lady shared his disturbance, and said,—

“My dear Werner, you know that many of the country-folk complain of the governor’s tyranny. In my opinion, it would be well for some of you, who can trust one another, to meet in secret, and take counsel how to throw off his wanton power.”

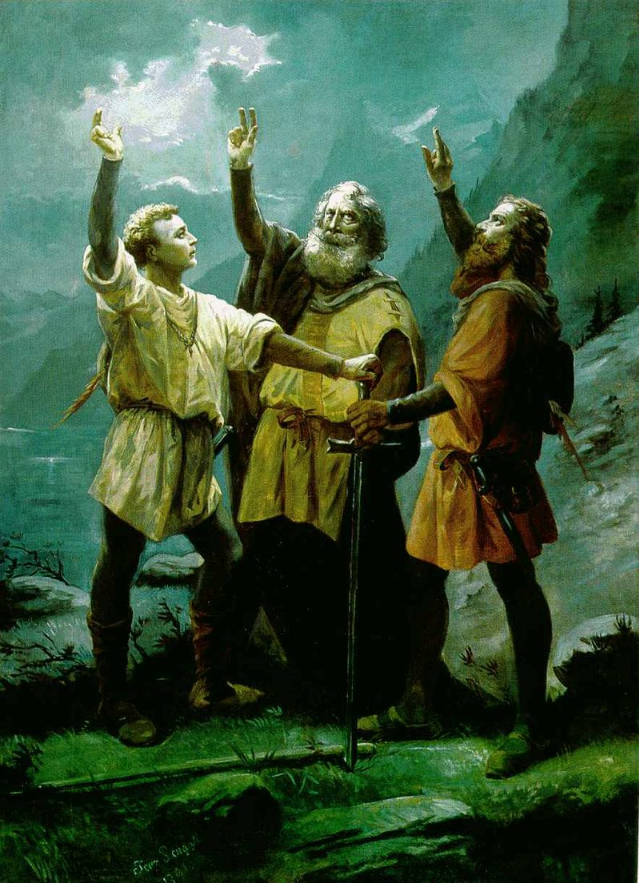

This advice seemed so judicious to Werner that he sought his friend Walter Fürst, and arranged with him and Arnold that they should meet and consider what steps to take, their place of meeting being at Rütli, a small meadow in a lonely situation, closed in on the land side by high rocks, and opening on the Lake of Lucerne. Others joined them in their patriotic purpose, and on the night of the Wednesday before Martinmas, in the year 1307, each of the three led to the place of meeting ten others, all as resolute and liberty-loving as themselves. These thirty-three good and true men, thus assembled at the midnight hour in the meadow of Rütli, united in a solemn oath that they would devote their lives and strength to the freeing of their country from its oppressors. They fixed the first day of the coming year for the beginning of their work, and then returned to their homes, where they kept the strictest secrecy, occupying themselves in housing their cattle for the winter and in other rural labors, with no indication that they cherished deeper designs.

During this interval of secrecy another event, of a nature highly exasperating to the Swiss, is said to have happened. It is true that modern critics declare the story of this event to be solely a legend and that nothing of the kind ever took place. However that be, it has ever since remained one of the most attractive of popular tales, and the verdict of the critics shall not deter us from telling again this oft-repeated and always welcome story.

We have named two of the many tyrannical governors of Switzerland, the deputies there of Albert of Austria, then Emperor of Germany, whose purpose was to abolish the privileges of the Swiss and subject the free communes to his arbitrary rule. The second named of these, Gessler, governor of Uri and Schwyz, whose threats had driven Werner to conspiracy, occupied a fortress in Uri, which he had built as a place of safety in case of revolt, and a centre of tyranny. “Uri’s prison” he called this fortress, an insult to the people of Uri which roused their indignation. Perceiving their sullenness, Gessler resolved to give them a salutary lesson of his power and their helplessness.

On St. Jacob’s day he had a pole erected in the market-place at Altdorf, under the lime-trees there growing, and directed that his hat should be placed on its top. This done, the command was issued that all who passed through the market-place should bow and kneel to this hat as to the king himself, blows and confiscation of property to be the lot of all who refused. A guard was placed around the pole, whose duty was to take note of every man who should fail to do homage to the governor’s hat.

On the Sunday following, a peasant of Uri, William Tell by name, who, as we are told, was one of the thirty-three sworn confederates, passed several times through the market-place at Altdorf without bowing or bending the knee to Gessler’s hat. This was reported to the governor, who summoned Tell to his presence, and haughtily asked him why he had dared to disobey his command.

“My dear lord,” answered Tell, submissively, “I beg you to pardon me, for it was done through ignorance and not out of contempt. If I were clever, I should not be called Tell. I pray your mercy; it shall not happen again.”

The name Tell signifies dull or stupid, a meaning in consonance with his speech, though not with his character. Yet stupid or bright, he had the reputation of being the best archer in the country, and Gessler, knowing this, determined on a singular punishment for his fault. Tell had beautiful children, whom he dearly loved. The governor sent for these, and asked him,—

“Which of your children do you love the best?”

“My lord, they are all alike dear to me,” answered Tell.

“If that be so,” said Gessler, “then, as I hear that you are a famous marksman, you shall prove your skill in my presence by shooting an apple off the head of one of your children. But take good care to hit the apple, for if your first shot miss you shall lose your life.”

“For God’s sake, do not ask me to do this!” cried Tell in horror. “It would be unnatural to shoot at my own dear child. I would rather die than do it.”

“Unless you do it, you or your child shall die,” answered the governor harshly.

Tell, seeing that Gessler was resolute in his cruel project, and that the trial must be made or worse might come, reluctantly agreed to it. He took his cross-bow and two arrows, one of which he placed in the bow, the other he stuck behind in his collar. The governor, meanwhile, had selected the child for the trial, a boy of not more than six years of age, whom he ordered to be placed at the proper distance, and himself selected an apple and placed it on the child’s head.

Tell viewed these preparations with startled eyes, while praying inwardly to God to shield his dear child from harm. Then, bidding the boy to stand firm and not be frightened, as his father would do his best not to harm him, he raised the perilous bow.

The legend deals too briefly with this story. It fails to picture the scene in the market-place. But there, we may be sure, in addition to Gessler and his guards, were most of the people of Uri, their hearts burning with sympathy for their countryman and hatred of the tyrant, their feelings almost wrought up to the point of attacking Gessler and his guards, and daring death in defence of their liberties. There also we may behold in fancy the brave child, scarcely old enough to appreciate the magnitude of his peril, but looking with simple faith into the kind eyes of his father, who stands firm of frame but trembling in heart before him, the death-dealing bow in his hand.

In a minute more the bow is bent, Tell’s unerring eye glances along the shaft, the string twangs sharply, the arrow speeds through the air, and the apple, pierced through its centre, is borne from the head of the boy, who leaps forward with a glad cry of triumph, while the unnerved father, with tears of joy in his eyes, flings the bow to the ground and clasps his child to his heart.

“By my faith, Tell, that is a wonderful shot!” cried the astonished governor. “Men have not belied you. But why have you stuck another arrow in your collar?”

“That is the custom among marksmen,” Tell hesitatingly answered.

“Come, man, speak the truth openly and without fear,” said Gessler, who noted Tell’s hesitancy. “Your life is safe; but I am not satisfied with your answer.”

“Then,” said Tell, regaining his courage, “if you would have the truth, it is this. If I had struck my child with the first arrow, the other was intended for you; and with that I should not have missed my mark.”

The governor started at these bold words, and his brow clouded with anger.

“I promised you your life,” he exclaimed, “and will keep my word; but, as you cherish evil intentions against me, I shall make sure that you cannot carry them out. You are not safe to leave at large, and shall be taken to a place where you can never again behold the sun or the moon.”

Turning to his guards, he bade them seize the bold marksman, bind his hands, and take him in a boat across the lake to his castle at Küssnach, where he should do penance for his evil intentions by spending the remainder of his life in a dark dungeon. The people dared not interfere with this harsh sentence; the guards were too many and too well armed. Tell was seized, bound, and hurried to the lake-side, Gessler accompanying.

The water reached, he was placed in a boat, his cross-bow being also brought and laid beside the steersman. As if with purpose to make sure of the disposal of his threatening enemy, Gessler also entered the boat, which was pushed off and rowed across the lake towards Brunnen, from which place the prisoner was to be taken overland to the governor’s fortress.

Before they were half-way across the lake, however, a sudden and violent storm arose, tossing the boat so frightfully that Gessler and all with him were filled with mortal fear.

“My lord,” cried one of the trembling rowers to the governor, “we will all go to the bottom unless something is done, for there is not a man among us fit to manage a boat in this storm. But Tell here is a skilful boatman, and it would be wise to use him in our sore need.”

“Can you bring us out of this peril?” asked Gessler, who was no less alarmed than his crew. “If you can, I will release you from your bonds.”

“I trust, with God’s help, that I can safely bring you ashore,” answered Tell.

By Gessler’s order his bonds were then removed, and he stepped aft and took the helm, guiding the boat through the storm with the skill of a trained mariner. He had, however, another object in view, and had no intention to let the tyrannical governor bind his free limbs again. He bade the men to row carefully until they reached a certain rock, which appeared on the lake-side at no great distance, telling them that he hoped to land them behind its shelter. As they drew near the spot indicated, he turned the helm so that the boat struck violently against the rock, and then, seizing the cross-bow which lay beside him, he sprang nimbly ashore, and thrust the boat with his foot back into the tossing waves. The rock on which he landed is, says the chronicler, still known as Tell’s Rock, and a small chapel has been built upon it.

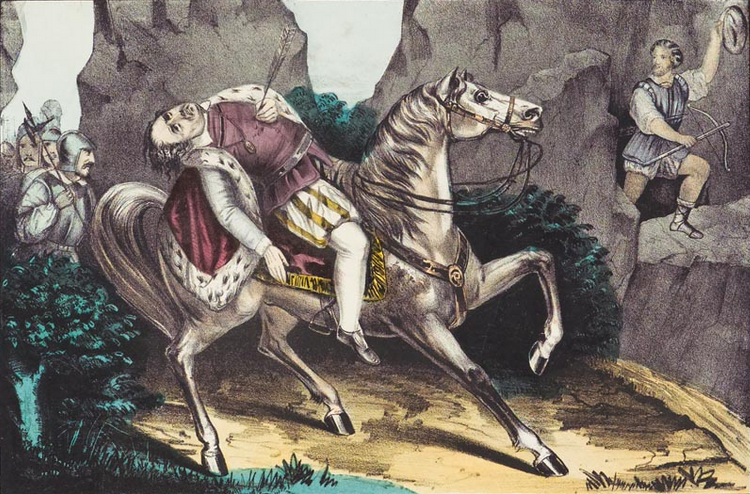

The story goes on to tell us that the governor and his rowers, after great danger, finally succeeded in reaching the shore at Brunnen, at which point they took horse and rode through the district of Schwyz, their route leading through a narrow passage between the rocks, the only way by which they could reach Küssnach from that quarter. On they went, the angry governor swearing vengeance against Tell, and laying plans with his followers how the runaway should be seized. The deepest dungeon at Küssnach, he vowed, should be his lot.

He little dreamed what ears heard his fulminations and what deadly peril threatened him. On leaving the boat, Tell had run quickly forward to the passage, or hollow way, through which he knew that Gessler must pass on his way to the castle. Here, hidden behind the high bank that bordered the road, he waited, cross-bow in hand, and the arrow which he had designed for the governor’s life in the string, for the coming of his mortal foe.

Gessler came, still talking of his plans to seize Tell, and without a dream of danger, for the pass was silent and seemed deserted. But suddenly to his ears came the twang of the bow he had heard before that day; through the air once more winged its way a steel-barbed shaft, the heart of a tyrant, not an apple on a child’s head, now its mark. In an instant more Gessler fell from his horse, pierced by Tell’s fatal shaft, and breathed his last before the eyes of his terrified servants. On that spot, the chronicler concludes, was built a holy chapel, which is standing to this day.

Such is the far-famed story of William Tell. How much truth and how much mere tradition there is in it, it is not easy to say. The feat of shooting an apple from a person’s head is told of others before Tell’s time, and that it ever happened is far from sure. But at the same time it is possible that the story of Tell, in its main features, may be founded on fact. Tradition is rarely all fable.

We are now done with William Tell, and must return to the doings of the three confederates to whom fame ascribes the origin of the liberty of Switzerland. In the early morning of January 1, 1308, the date they had fixed for their work to begin, as Landenberg was leaving his castle to attend mass at Sarnen, he was met by twenty of the mountaineers of Unterwald, who, as was their custom, brought him a new-year’s gift of calves, goats, sheep, fowls, and hares. Much pleased with the present, he asked the men to take the animals into the castle court, and went on his way towards Sarnen.

But no sooner had the twenty men passed through the gates than a horn was loudly blown, and instantly each of them drew from beneath his doublet a steel blade, which he fixed upon the end of his staff. At the sound of the horn thirty other men rushed from a neighboring wood, and made for the open gates. In a very few minutes they joined their comrades in the castle, which was quickly theirs, the garrison being overpowered.

Landenberg fled in haste on hearing the tumult, but was pursued and taken. But as the confederates had agreed with each other to shed no blood, they suffered this arch villain to depart, after making him swear to leave Switzerland and never return to it. The news of the revolt spread rapidly through the mountains, and so well had the confederates laid their plans, that several other castles were taken by stratagem before the alarm could be given. Their governors were sent beyond the borders. Day by day news was brought to the head-quarters of the patriots, on Lake Lucerne, of success in various parts of the country, and on Sunday, the 7th of January, a week from the first outbreak, the leading men of that part of Switzerland met and pledged themselves to their ancient oath of confederacy. In a week’s time they had driven out the Austrians and set their country free.

It must be admitted that there is no contemporary proof of this story, though the Swiss accept it as authentic history, and it has not been disproved. The chief peril to the new confederacy lay with Albert of Austria, the dispossessed lord of the land, but the patriotic Swiss found themselves unexpectedly relieved from the execution of his threats of vengeance. His harshness and despotic severity had made him enemies alike among people and nobles, and when, in the spring of 1308, he sought the borders of Switzerland, with the purpose of reducing and punishing the insurgents, his career was brought to a sudden and violent end.

A conspiracy had been formed against him by his nephew, the Duke of Swabia, and others who accompanied him in this journey. On the 1st of May they reached the Reuss River at Windisch, and, as the emperor entered the boat to be ferried across, the conspirators pushed into it after him, leaving no room for his attendants. Reaching the opposite shore, they remounted their steeds and rode on while the boat returned for the others. Their route lay through the vast cornfields at the base of the hills whose highest summit was crowned by the great castle of Hapsburg.

They had gone some distance, when John of Swabia suddenly rushed upon the emperor, and buried his lance in his neck, exclaiming, “Such is the reward of injustice!” Immediately two others rode upon him, Rudolph of Balm stabbing him with his dagger, while Walter of Eschenbach clove his head in twain with his sword. This bloody work done, the conspirators spurred rapidly away, leaving the dying emperor to breathe his last with his head supported in the lap of a poor woman, who had witnessed the murder and hurried to the spot.

This deed of blood saved Switzerland from the vengeance which the emperor had designed. The mountaineers were given time to cement the government they had so hastily formed, and which was to last for centuries thereafter, despite the efforts of ambitious potentates to reduce the Swiss once more to subjection and rob them of the liberty they so dearly loved.

[…] Source link […]

5