Editor’s Note: The following account is taken from Historical Tales, Vol. 6, by Charles Morris (published 1896).

Charlemagne, the great king, had built himself an empire only surpassed by that of ancient Rome. All France was his; all Italy was his; all Saxony and Hungary were his; all western Europe indeed, from the borders of Slavonia to the Atlantic, with the exception of Spain, was his. He was the bulwark of civilization against the barbarism of the north and east, the right hand of the church in its conflict with paganism, the greatest and noblest warrior the world had seen since the days of the great Caesar, and it seemed fitting that he should be given the honor which was his due, and that in him and his kingdom the great empire of Rome should be restored.

Augustulus, the last emperor of the west, had ceased to reign in 476. The Eastern Empire was still alive, or rather half-alive, for it was a life without spirit or energy. The empire of the west had vanished under the flood of barbarism, and for more than three centuries there had been no claimant of the imperial crown. But here was a strong man, a noble man, the lord and master of a mighty realm which included the old imperial city; it seemed fitting that he should take the title of emperor and rule over the western world as the successor of the famous line of the Caesars.

So thought the pope, Leo III, and so thought his cardinals. He had already sent to Charlemagne the keys of the prison of St. Peter and the banner of the city of Rome. In 799 he had a private interview with the king, whose purpose no one knew. In August of the year 800, having settled the affairs of his wide-spread kingdom, Charlemagne suddenly announced in the general assembly of the Franks that he was about to make a journey to Rome. Why he went he did not say. The secret was not yet ready to be revealed.

On the 23d of November the king of the Franks arrived at the gates of Rome, a city which he was to leave with the time-honored title of Emperor of the West. “The pope received him as he was dismounting; then, on the next day, standing on the steps of the basilica of St. Peter and amidst general hallelujahs, he introduced the king into the sanctuary of the blessed apostle, glorifying and thanking the Lord for this happy event.”

In the days that followed, Charlemagne examined the grievances of the Church and took measures to protect the pope against his enemies. And while he was there two monks came from Jerusalem, bearing with them the keys of the Holy Sepulchre and Calvary, and the sacred standard of the holy city, which the patriarch had intrusted to their care to present to the great king of the Franks. Charlemagne was thus virtually commissioned as the defender of the Church of Christ and the true successor of the Christian emperors of Rome.

Meanwhile, Leo had called a synod of the Church to consider whether the title of emperor should not be conferred on Charles the Great. At present, he said, the Roman world had no sovereign. The throne of Constantinople was occupied by a woman, the Empress Irene, who had usurped the title and made it her own by murder. It was intolerable that Charles should be looked on as a mere patrician, an implied subordinate to this unworthy sovereign of the Eastern Empire. He was the master of Italy, Gaul, and Germany, said Leo. Who was there besides him to act as Defender of the Faith? On whom besides could the Church rest, in its great conflict with paganism and unbelief?

The synod agreed with him. It was fitting that the great king should be crowned emperor, and restore in his person the ancient glory of the realm. A petition was sent to Charles. He answered that, however unworthy of the honor, he could not resist the desire of that august body. And thus was formally completed what probably had been the secret understanding of the pope and the king months before. Charles, king of the Franks, was to be given the title and dignity of Charles, Emperor of the West.

The season of the Feast of the Nativity, Christmas-day of the year 800, duly came. It was destined to be a great day in the annals of the Roman city. The chimes of bells which announced the dawning of that holy day fell on the ears of great multitudes assembled in the streets of Rome, all full of the grand event that day to be consummated, and rumors of which had spread far and wide. The great basilica of St. Peter was to be the scene of the imposing ceremony, and at the hour fixed its aisles were crowded with the greatest and most devoted and enthusiastic assemblage it had ever held, all eager to behold and to lend their support to the glorious act of coronation, as they deemed it, fixed for that day, an act which, as they hoped, would restore Rome to the imperial position which that great city had so many centuries held.

It was a noble pile, that great cathedral of the early church. It had been recently enriched by costly gifts set aside by Charles from the spoils of the Avars, and converted into the most beautiful of ornaments consecrated to the worship of Christ. Before the altar stood the golden censers, containing seventeen pounds weight of solid gold. Above gleamed three grand coronas of solid silver, of three hundred and seven pounds in weight, ablaze with a glory of wax-lights, whose beams softly illuminated the whole great edifice. The shrine of St. Peter dazzled the eyes by its glittering “rufas,” made of forty-nine pounds of the purest gold, and enriched by brilliant jewels till they sparkled like single great gems. There also hung superb curtains of white silk, embroidered with roses, and with rich and intricate borders, while in the centre was a splendid cross worked in gold and purple. Suspended from the keystone of the dome hung the most attractive of the many fine pictures which adorned the church, a peerless painting of the Saviour, whose beauty drew all eyes and aroused in all souls fervent aspirations of devoted faith. Never had Christian church presented a grander spectacle; never had one held so immense and enthusiastic and audience; for one of the greatest ceremonies the Christian world had known was that day to be performed.

Through the wide doors of the great church filed a procession of bronzed veterans of the Frankish army; the nobility and the leading people of Rome; the nobles, generals, and courtiers who had followed Charlemagne thither; warriors from all parts of the empire, with their corslets and winged helmets of steel and their uniforms of divers colors; civic functionaries in their gorgeous robes of office; dignitaries of the church in their rich vestments; a long array of priests in their white dalmatics, until all Christendom seemed present in its noblest and most showy representatives. Heathendom may have been represented also, for it may be that messengers from the great caliph of Bagdad, the renowned Haroun al Raschid, the hero of the “Arabian Nights’ Entertainments,” were present in the church. Many members of the royal family of Charlemagne were present to lend dignity to the scene, and towering above them all was the great Charles himself, probably clad in Roman costume, his garb as a patrician of the imperial city, which dignity had been conferred upon him. Loud plaudits welcomed him as he rose into view. There were many present who had seen him at the head of his army, driving before him hosts of flying Saracens, Saxons, Lombards, and Avars, and to them he was the embodiment of earthly power, the mighty patron of the church, and the scourge of pagans and infidels; and as they gazed on his noble form and dignified face it seemed to some of them as if they looked with human eyes on the face and form of a representative of the Deity.

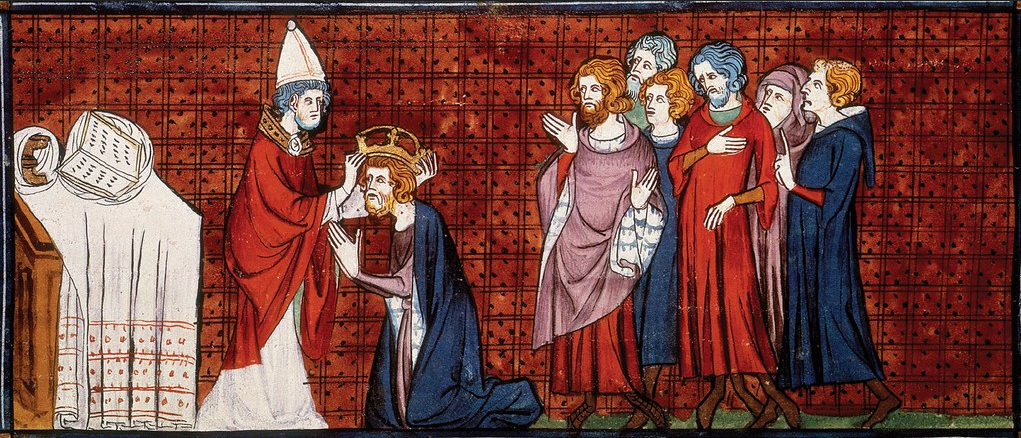

A solemn mass was sung, with all the impressive ceremony suitable to the occasion. As the king rose to his feet, or while he still kneeled before the altar and the “confession” – the tomb of St. Peter – the pope, as if moved by a sudden impulse, took up a splendid crown which lay upon the altar, and placed it on his brow, saying, in a loud voice, “Long life and victory to Charles, the most pious Augustus, crowned by God the great and pacific Emperor of the Romans!”

A solemn mass was sung, with all the impressive ceremony suitable to the occasion. As the king rose to his feet, or while he still kneeled before the altar and the “confession” – the tomb of St. Peter – the pope, as if moved by a sudden impulse, took up a splendid crown which lay upon the altar, and placed it on his brow, saying, in a loud voice, “Long life and victory to Charles, the most pious Augustus, crowned by God the great and pacific Emperor of the Romans!”

At once, as if this were a signal for the breaking of the constrained silence, a mighty shout rose from the whole vast assembly. Again and again it was repeated, and then broke out the solemn chant of the litany, sung by hundreds of voices, while Charlemagne stood in dignified and patient silence. Whether or not this act of the pope was a surprise to him we have no assurance. Eginhard tells us that he declared he would not have entered the church that day if he had foreseen the pope’s intentions; yet it is not easy to believe that he was ignorant of or non-consenting to the coming event. At the close of the chant Leo prostrated himself at the feet of Charlemagne, and paid him adoration, as had been the custom in the days of the old emperors. He then anointed him with holy oil. And from that day forward Charles, “giving up the title of patrician, bore that of emperor and Augustus.”

The ceremonies ended in the presentation from the emperor to the church of a great silver table, and, in conjunction with his son Charles and his daughters, of golden vessels belonging to the table of five hundred pounds’ weight. This great gift was followed, on the Feast of the Circumcision, with a superb golden corona to be suspended over the altar. It was ornamented with gems, and contained fifty pounds of gold. On the Feast of the Epiphany he added three golden chalices, weighing forty-two pounds, and a golden paten of twenty-two pounds’ weight. To the other churches also, and to the pope, he made magnificent gifts, and added three thousand pounds of silver to be distributed among the poor.

Thus, after more than three centuries, the title of Augustus was restored to the western world. It was destined to be held many centuries thereafter by the descendants of Charlemagne. After the division of his empire into France and Germany, the imperial title was preserved in the latter realm, the fiction – for it was little more – that an emperor of the west existed being maintained down to the present century.

As to the influence exerted by the power and dominion of Charlemagne on the minds of his contemporaries and successors, many interesting stories might be told. Fable surrounded him, legend attached to his deeds, and at a later date he shared the honor given to the legendary King Arthur of England, of being made a hero of romance, a leading character in many of those interminable romances of chivalry which formed the favorite reading of the mediaeval age.

But we need not go beyond his own century to find him a hero of romance. The monk of the abbey of St. Gall, in Switzerland, whose story of the defences of the land of the Avars we have already quoted, has left us a chronicle full of surprising tales of the life and doings of Charles the Great. One of these may be of interest, as an example of the kind of history with which our ancestors of a thousand years ago were satisfied.

Charlemagne was approaching with his army Pavia, capital of the Lombards. Didier, the king, was greatly disquieted at his approach. With him was Ogier the Dane (Ogger the monk calls him), one of the most famous captains of Charlemagne, and a prominent hero of romance. He had quarreled with the king and had taken refuge with the king of the Lombards. Thus goes the chronicler of St. Gall:

“When Didier and Ogger heard that the dread monarch was coming, they ascended a tower of vast height, where they could watch his arrival from afar off and from every quarter. They saw, first of all, engines of war such as must have been necessary for the armies of Darius or Julius Caesar.

“‘Is not Charles,’ asked Didier of Ogger, ‘with this great army?’

“But the other answered, ‘No.’ The Lombard, seeing afterwards an immense body of soldiery gathered from all quarters of the vast empire, said to Ogger, ‘Certainly, Charles advances in triumph in the midst of this throng.’

“‘No, not yet; he will not appear so soon,’ was the answer.

“‘What should we do, then,’ rejoined Didier, who began to be perturbed, ‘should he come accompanied by a larger band of warriors?’

“‘You will see what he is when he comes,’ replied Ogger; ‘but as to what will become of us I know nothing.’

“As they were thus parleying, appeared the body of guards that knew no repose; and at this sight the Lombard, overcome with dread, cried, ‘This time it is surely Charles.’

“‘No,’ answered Ogger, ‘not yet.’

“In their wake came the bishops, the abbots, the ordinaries of the chapels royal, and the counts; and then Didier, no longer able to bear the light of day or to face death, cried out with groans, ‘Let us descend and hide ourselves in the bowels of the earth, far from the face and the fury of so terrible of foe.’

“Trembling the while, Ogger, who knew by experience what were the power and might of Charles, and who had learned the lesson by long consuetude in better days, then said, ‘When you shall behold the crops shaking for fear in the fields, and the gloomy Po and the Ticino overflowing the walls of the city with their waves blackened with steel, then you may think that Charles is coming.’

“He had not ended these words when there began to be seen in the west, as it were a black cloud raised by the northwest wind or by Boreas, which turned the brightest day into awful shadows. But as the emperor drew nearer and nearer, the gleam of arms caused to shine on the people shut up within the city a day more gloomy than any kind of night. And then appeared Charles himself, that man of steel, with his head encased in a helmet of steel, his hands garnished with gauntlets of steel, his heart of steel and his shoulders of marble protected by a cuirass of steel, and his left hand armed with a lance of steel which he held aloft in the air, for as to his right hand, he kept that continually on the hilt of his invincible sword. The outside of his thighs, which the rest, for their greater ease in mounting on horseback, were wont to leave unshackled even by straps, he wore encircled by plates of steel. What shall I say concerning his boots? All the army were wont to have them invariably of steel; on his buckler there was naught to be seen but steel; his horse was of the color and the strength of steel.

“All those who went before the monarch, all those who marched by his side, all those who followed after, even the whole mass of the army, had armor of the like sort, so far as the means of each permitted. The fields and the highways were covered with steel; the points of steel reflected the rays of the sun; and this steel, so hard, was borne by people with hearts still harder. The flash of steel spread terror throughout the streets of the city. ‘What steel! alack, what steel!’ Such were the bewildered cries the citizens raised. The firmness of manhood and of youth gave way at sight of the steel; and the steel paralyzed the wisdom of graybeards. That which I, poor tale-teller, mumbling and toothless, have attempted to depict in a long description, Ogger perceived at one rapid glance, and said to Didier, ‘Here is what you so anxiously sought,’ and whilst uttering these words he fell down almost lifeless.”

If our sober chronicler of the ninth century could thus let his imagination wander in speaking of the great king, what wonder that the romancers of a later age took Charlemagne and his Paladins as fruitful subjects for their wildly fanciful themes!

5