Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Historical Essays and Reviews, by Mandell Creighton (published 1902).

I must own to a desire for a fuller recognition of the fact that English history is at the bottom a provincial history. This truth is chiefly left to be exhibited by novelists and poets. The historian and the archæologist investigate with care the separate origins of the early kingdoms, the steps by which they came under the overlordship of the West Saxon kings, and their incorporation into a consolidated kingdom under the Norman successors of the West Saxon line. But at this point they generally cease their inquiries. The history of the central kingdom, the progress of the central administration, becomes so important and so full of interest that it absorbs all else. It is true that curious customs are noted by the archæologist, and that particular institutions force themselves into notice. But the vigorous undercurrent of a strong provincial life in different parts of England is seldom seriously considered by historians. Yet the moment that English life is approached from the imaginative side, it is this strong provincial life that attracts attention. Our great novels are not English, but provincial. Our best-known types of character are developed within distant areas, and owe their expressiveness to local circumstances.

“Squire Western,” “Job Barton,” “Mrs. Poyser,” “Andrew Fairservice,” Tennyson’s Northern Farmer, all live amid definite surroundings, and all are racy of the soil which bore them. I am sure that no better service can be rendered by an archæological society to historical study than an attempt to bring the characteristic features of different parts of England into due prominence. Archæology has done much for history in the past. It has ofttimes gathered evidence when written records are silent. It has pieced together fragments of the life of days of old when the human voice was still inaudible. It has settled disputed points by appeals to the eye on which there could be no doubt. In archæology, as in all other sciences, there are those who say that almost all has been done that can be done. The records of stones have been ransacked, explored, classified and interpreted. Even if this were so, which is scarcely the case, there remain innumerable traces of the past, still unrecognised and unsuspected. Local character, habits, institutions, modes of thought and observation, are all the result of a long process, differing in different parts of England. They are only to be seen and understood by a sympathetic searcher and observer who looks upon each part of England in the light of its past, who sees that past, not only in ancient buildings, here and there, but on the whole face of the land, and in the hearts and lives of its inhabitants. I admit that this is no easy task. I admit that the results of such inquiry must at first be very hypothetical, and its conclusions tentative. But I think that the inquiry is well worth pursuing; and it must be pursued speedily, if at all.

Of this provincial history, no part of England possesses clearer traces than does Northumberland. It has always held the same position in English history from its very beginning. It has always been a Borderland. It is true that the Border has varied in extent; but whether it was great or small Northumberland has always been within it, and has generally formed its chiefest part. But we are met at the outset of our inquiry by the question, How came there to be a Border-land at all? The answer to this question brings into prominence a part of English history which it is too much the fashion to neglect. The northern Border-land was the creation of the Romans, who mapped it out with accuracy and defined its limits. If I were asked, What permanent results are left of the Roman occupation of Britain? I should answer that they marked out the territory between the Solway and the Clyde on the west, and the Tyne and the Forth on the east, to be a land of contention and debate, and that it remained with the character that they impressed upon it, down to the middle of last century.

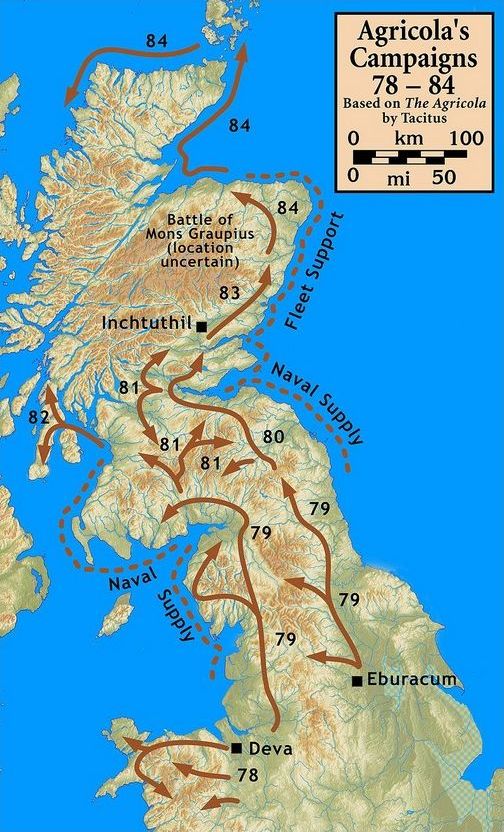

If we were so careful of our early history as are some folk, we would erect upon the wilds of Redeswire a statue of C. Julius Agricola as the founder of our Border State, the originator of the elaborate constitution contained in the Leges Marchiarum, and other such like documents. It was Agricola who consolidated the Roman province in Britain, and first faced the difficulties of determining its limits. We know how in his first campaign he conquered the Ordovices and reduced the Isle of Mona. In his second campaign he brought into subjection the tribes of the western coast between the Dee and the Solway. He was careful to make good every step of his way, and keep open his communications. The trees fell before the axe of the legionary, and a rude but sufficient road was opened. Every night the Roman camp was occupied in some secure position, every day chronicled a steady advance of the invader. Permanent forts were raised in advantageous spots, and Agricola showed both the fire of a general and the sagacity of an explorer. From the Solway his forts most probably ran along the Eden and the Irthing to the Tyne. He found a narrow neck of land which he could occupy with ease, and by holding it secure his retreat. Then in his third campaign he advanced against “new peoples,” tribes who as yet had not felt the arms of Rome. He penetrated, it would seem, to the Tay, and then again paused to secure the territory which he had acquired. Again, he occupied a narrow neck of land between the Clyde and the Forth. This was occupied by forts “so that the foe,” says Tacitus, “were driven almost into another island”. I need not follow Agricola’s course of conquest to the Grampian Hills, nor his voyage of circumnavigation, nor his projected reduction of Ireland. Agricola’s career came to an end, and with it came to an end any plan for extending Rome’s sway over the whole of the British Isles. The only question which was considered by his successors was the boundary of the Roman Province. Should they take of forts by which the northern or the southern line Agricola had secured his conquests for the time? Rome’s statesmanship and Rome’s generalship never again contemplated the execution of Agricola’s design of a complete conquest. For a time opinions wavered which boundary to choose. At length the line of forts along the Tyne and the Irthing was selected to mark the region south of which the “peace of Rome” was to be carefully maintained. The mighty rampart, which Dr. Bruce has taught us to call the wall of Hadrian, was erected as a majestic symbol of the permanence of Roman sway, as a dividing line between civilisation and barbarism. But this was done without prejudice to the future extension of the Roman occupation to Agricola’s farther line of forts. The Roman province was to stretch in full security as far as the Tyne and the Solway. Rome’s influence was to be felt as far as the Clyde and the Forth. Two great Roman roads, each with several branches, passed northwards through the wall. Watling Street, with its supporting stations of Habitancum and Bremenium, traversed this county. The whole of Northumberland and the Scottish Lowlands are covered with traces of Roman and British camps, which tell clearly enough the tale of Border warfare in the earliest days of our history. They tell of a long period of constant struggle, of troops advancing and retreating, of a territory held with difficulty, of perpetual alternations of fortune. In the days of the Roman occupation the Border wears its distinctive features. Its future history is a changing repetition of the same details.

But though we may generally gather that this was the history of the Roman Border, many puzzling questions remain. Why did the Romans fix their boundary where they did? The military reason of obtaining a narrow tract of land to fortify was no doubt a strong one. But the Romans were a practical people and wished to make their province of Britain a profitable possession. It may be that the valley of the Tyne was the most northern point where they saw a prospect of making agriculture immediately remunerative. By the Tyne Valley they established their boundary, and only kept such a hold of the country to the north as might help to secure the Tyne Valley from invasion. It proved to be a difficult and in the end an impossible task. The sturdy tribes of the north learned to value at its true worth the intolerable boon of Roman civilisation, the colonist, the tribute and the tithe corn. In their moorland forts they resisted to the utmost. Constant warfare increased their discipline and power of combination. The growing wealth of the province offered a richer prize to their rapacity. Ever watchful for an opportunity they broke through the line of the wall and swept like a storm-cloud over the southern fields. Much, very much, has been done in explaining the Roman Wall as illustrative of the life of the Romans. Something remains to be done in studying it as illustrating the character of those whom it was built to repel. I could conceive it possible that an archæologist who was skilled in military science, and had the power of reproducing in his mind the local features of a bygone time—that one so gifted might make a military survey of the country round the Wall, which would be full of suggestiveness for a picture of British life. I must own that the Wall is to me more interesting for the impression which it gives of the power of the Britons than of the mightiness of Rome. We know Rome’s greatness from many other memorials. We know the bravery of the Britons only by the reluctant testimony of their enemies.

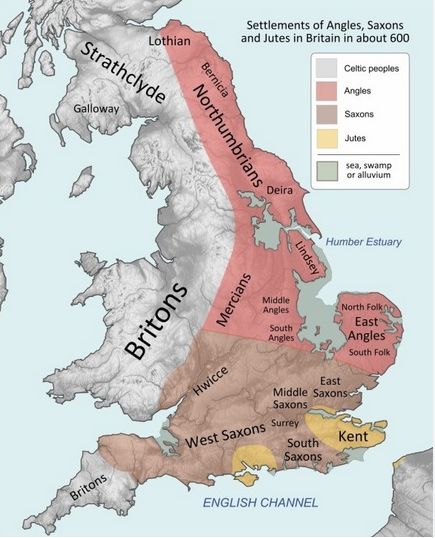

As we muse upon the ruins of Borcovicus another question strikes us. How came it that the men who so stubbornly resisted the massive legionaries of Rome, who marched against them in their thousands, gave way before the onslaughts of the Angles who came in small bands in their boats? It would seem that the need of resistance to Rome had called into being a premature organisation, a reckless patriotism, which produced a rapid reaction and degeneracy. The very greatness of Rome’s power warned the Britons of their danger. Its advance was steady and threatened to spread northwards over the land. The Angles who settled along the east coast and passed up the river valleys did not awaken the same dread, or call out the same feeling of national danger. But the insidious progress of the colonist was more deadly than the warlike advance of the invader. Little by little the Britons were thrust into the hill country of the west. The line of the coast and the river valleys were gradually occupied by the clearings of the Angles. The land was still a Border-land, but the line of the Border no longer ran between north and south, but between east and west. When Ida, whom the fearful Britons called the Flamebearer, combined into a kingdom the scattered settlements of a common folk, it was in the Roman Border-land that those settlements began. They reached from the Tweed Valley northwards and southwards, till Ida occupied the rock of Bamborough as a central point, and then extended his domain to the Tees.

The question of the Border between Briton and Angle, between east and west, was long contended and with varying results. The Britons on their side again united into the kingdom of Strathclyde, north of which was the Scottish kingdom of Dalriada. I will not impose upon your time and patience by tracing the variations of this western boundary. It will be enough to recall a few points of interest in the struggle. In 603 the combined army of Britons and Scots advanced to attack Æthelfrith’s Northumbrian kingdom. They entered the vale of the Liddell, whence one pass leads into the valley of the Teviot and the Tweed, while another leads into the North Tyne. Here at a spot which Bede calls Dægsastan, a name still preserved in Dawstaneburn and Dawstanerig, was fought a battle which determined for many years the security of the Northumbrian Border. “From that time,” says Bede, triumphantly, “no Scot king dared to come into Britain to war with the English to this day.” The Angles recognised on this spot the weakness of their boundary, and copied the example of Rome. The remains of a huge earthen rampart, known as the Catrail, may still be traced along the wild moorland or hard by the spot where Dægsastan had run with blood.

I recall this event because it is a definite mark of an important point in our provincial history. The boundary from east to west led to the severance of Cumbria from Northumbria. The English desired only to secure, not to extend, their dominion westward. They weakened the kingdom of Strathclyde by driving a wedge of settlers into the tableland which lay in its midst. They penetrated along the valley of the Irthing, along the Maiden Way, into the central plain, which gained from them the name of Inglewood; but they left the mountainous district to the Britons.

I need not recall the great days of the Northumbrian kingdom, the heroic times of early Christianity, when the lamp of civilisation burned brightly in the Columbite monastery of Lindisfarne, and was reflected from the royal house of Bamborough. This period of greatness, though of immense importance to English history, is unfortunately only an episode in the history of this district as a whole. Yet there is no spot in England more fitted to awaken a deep sense of gratitude to the past than is the land which lies beneath the castle of Bamborough. No works of man have effaced the traces of the past. The rocks remain amid the surging of the waves, as when Cuthbert heard amongst them the wails of men’s souls in the eternal conflict between good and evil. The village clusters for protection at the foot of the royal castle, much as it did when it was fired by Penda’s host. The sloping uplands are dotted by scattered farms, in which may still be traced the progressive clearings of the English settlers. The ruins of the monastery of Lindisfarne still hide themselves behind a sheltering promontory of rock, that they may escape the eye of the heathen pirate who swept the northern seas. There is no place which tells so clearly the story of the making of England.

I pass by the days of the Northumbrian supremacy, which ended with Egfrith’s defeat at Nechtansmere, where the Pictish king avenged the slaughter of Dægsastan. “From this time,” says Bede, “the hopes and strength of the kingdom of the English began to ebb.” The Northumbrian kingdom still pursued its career of literary and ecclesiastical activity at Jarrow, Wearmouth and Streaneshalch. It did not pass away till it had produced an historian of its greatness. But its boundaries, north and west, were ill secured. Its premature progress gave way to social and political disorganisation. The long, black ships of the Danish pirates spread ruin amidst the numerous monastic houses which fringed the eastern coast. The Scots of Dalriada established their supremacy over the Picts, and a strong Scottish power ravaged the district between the Forth and the Tweed. But Scots and English alike soon fell before the arms of the Danes who came as invaders, and conquered and settled as they would. Churches and monasteries were especially hateful to the heathen Danes. Their buildings were burnt, their treasures were scattered, their libraries were destroyed. The work of Benedict Biscop, of Wilfrid and of Bede, was all undone. The civilisation of Northumbria was well-nigh swept away. Only round the relics of the saintly Cuthbert a little band of trembling monks still held together, and wandered from place to place, kept steadfast by their faith that Cuthbert would not forsake them. It was the West Saxon Ælfred that checked the career of Danish conquest; it was his wisdom that prepared a way whereby the Danes ceased to be formidable, and became a new but not alien element of English life.

The Danish settlement had little effect on the northern part of the Northumbrian kingdom. The Danes chose Deira, not Bernicia; their traces are found in Yorkshire, not in Northumberland. Their incorporation into English civilisation and the limits of their settlement in Northumbria are alike illustrated by the story of Guthred. To escape a civil war amongst themselves they listened to the counsels of Ælfred, aided by Eadred, the prior of the wandering monks at Lindisfarne. Eadred counselled them to choose as their king Guthred, a young man of the royal blood, who had been sold as a slave to a widow woman at Whittingham. Guthred, grateful for St. Cuthbert’s aid, settled his brethren at Cunecacestre, now Chesterle-Street, and gave as the patrimony of St. Cuthbert the land between the Tyne and the Tees, with privilege of sanctuary. This was the beginning of another step in our provincial history. It was the origin of what was known till very recent times as The Bishopric. It was the foundation of the authority of the Prince-Bishops of Durham. It marks the cause which severed the county of Durham from the county of Northumberland.

The Danish kingdom in Deira ran its course, and in due time submitted to the lordship of the West Saxon king. In Bernicia, meanwhile, members of the old royal house were allowed to rule over their devastated lands, for which they paid tribute to their Danish lords. When the Danes made submission to Eadward the Elder the men of Bernicia submitted likewise. But the men of the north were unruly subjects, and were hard to reduce into harmony with the men of the south. Edmund and Eadred both strove to make a peaceful settlement of their northern frontier. Edmund gave Cumberland to Malcolm, King of Scots, on condition that he should be his “fellow-worker by land and sea”. He wished to show that there need be no collision of interest between England and Scotland. It was a question for decision on grounds of expediency, how order could best be kept in the doubtful portions of Northumbria and Strathclyde. Edmund handed over this responsibility, as far as Cumberland was concerned, to the Scottish king, and the plan succeeded. In later days William Rufus reclaimed the district south of the Solway, and so fixed the definite boundary of the English kingdom on the western side. Eadred had still to face the difficulty of dealing with Northumbrian independence, which had degenerated into anarchy and disorder. The last king was driven out, and an earl was set to rule in his stead; but so strong was local feeling that the earl was chosen from the old house of the lords of Bamborough. Eadred’s successor, Edgar, ventured a step farther, and divided this great earldom into two. Moreover he followed Edmund’s example of friendly dealings with the Scottish king. The land north of the Tweed was of little value to the English. Lothian was ceded to the Scottish king, most probably by Edgar, though it was afterwards recovered, but finally ceded in 1016.

The hopes of Edgar that Northumberland would settle into peace and order were destroyed by the renewed invasion of the Northmen. Again all was in confusion. Again the terrified monks bore off St. Cuthbert’s body that they might save it from sacrilege. Their wanderings were miraculously stayed, so goes the legend, upon a hill-top amid the waving woods that clad a bold promontory round which flowed the waters of the Wear. This hill-top of Dunholm was chosen as the site on which rose the mighty minster that holds St. Cuthbert’s shrine. The saint left the bleaker regions farther north which he had loved so well. The outward signs of devotion for his memory were not to gather round the scenes of his labours. The chief centre of ecclesiastical civilisation was henceforth fixed far away from Bamborough, on a spot which had no associations with the old days of Northumbria’s greatness. This northern district was abandoned by its patron saint, as though a destined theatre for acts of lawlessness and deeds of blood.

The lawlessness and barbarism of Northumberland in these days, we know from the history of its earls. Uhtred, who sprang from the old line of the lords of Bamborough, covenanted, as a condition of his marriage with a citizen’s daughter, to espouse the blood-feud of his father-in-law and slay for him his enemy. Though the marriage was broken off and the covenant was unfulfilled, the enemy who had been threatened bided his time, and slew Uhtred in the presence of King Cnut. The feud was carried on by Uhtred’s son, who slew his father’s slayer, and was himself pursued in turn. The two foes grew weary of their lives, spent in perpetual dread; they were reconciled, and undertook together a pilgrimage to Rome. But the sea was tempestuous, and they shrank before the voyage. They agreed to dispense with the solemn religious vow and to return home in peace. But on the way home the old savage passion for revenge revived, and one slew his unsuspecting fellow as they rode together through the forest of Risewood. We see the growth of the wild spirit which supplied the material for the Border feuds of later days.

Still, lawless as Northumberland might be, it could not forget the days of its former greatness. Though it could no longer hope for supremacy, it struggled at least for independence. Its resistance to the family of Godwine, its rejection of Tostig for its earl, caused dissension within the house which seemed to hold England’s future in its hands. The refusal of Northumberland to help King Harold was one great cause, we cannot say how great, of the victory of the Norman William by the “hoar apple-tree” on the hill of Senlac. Perhaps the Northumbrians hoped under William’s rule to establish their independence. But William was not the man to allow the formation of a middle kingdom. He soon learned the lawlessness of the Northumbrian temper. His first earl, though of English blood, was attacked at Newburn, and the church in which he sought shelter was burned to the ground. His second earl was driven away by a revolt. His third earl, a Norman, was massacred in Durham with all his men. William saw the gathering danger threatened by this northern love for independence. His answer to the northern revolt was swift and decided. He let men feel his starkness by his remorseless harrying of the north. The lands between the Humber and the Tees, and then the lands of the Bishopric, were reduced to a waste. The population fell by the sword or died of hunger. Northumberland was left powerless for any further revolt of a serious kind. The southern portion of the old kingdom, Deira, lost all outward sign of its former position, Its old independence needed no further recognition, and no earl was appointed for South Northumberland. Hence the old name was transferred entirely to the northern part, which being a Border-land against the Scots still needed some responsible governor. That northern part, which is far north of the Humber, alone retained the name which can recall the memories of the greatness of the Northumbrian kingdom.

But though the independence of the north had been thoroughly broken by systematic devastation, still William paid some heed to its local feeling by giving it an earl sprung from the old Northumbrian line. Though he did so, he regarded Earl Waltheof with a jealous eye, and demanded from him a loyalty which he did not find in his Norman barons. Slight cause for suspicion brought upon Waltheof condign punishment, and William knew no mercy for the last English earl, whose tomb at Crowland men visited as that of a martyr and a saint. William then conferred the earldom of Northumberland on the Lotharingian, Walcher, Bishop of Durham. Again the lawless spirit of the Northumbrians broke out, and they took prompt revenge on the Bishop for a misdeed which he did not punish to their liking. At a moot, held by a little chapel at Gateshead, the men of the Tyne and Rede gathered in numbers. As the talk went on, a cry was raised, “Short rede, good rede, slay ye the Bishop!” and Walcher was slaughtered at the chapel door. Again Northumberland was harried, and Robert, the King’s son, on his way from Scotland, laid the foundation of a castle opposite the spot where Bishop Walcher had been slain. Its walls rose as a solid and abiding warning to a turbulent folk. Near it were the remains of a Roman bridge across the Tyne

—Pons Elii, the bridge that the Emperor Ælius Hadrianus had built. Hard by was the little township of Pandon and some remains of a camp, which may have afforded shelter to the monks, and so gained the name of Monkchester. In distinction to the ruins of this old camp, the rising fortress was called the new castle. Soon a population gathered round it which extended to Pandon and Monkchester alike, and these old names were absorbed into that of Newcastle.

Nor was the fortress of Newcastle the only sign of the presence of the conquering Normans. The three great baronies of Redesdale, Mitford and Morpeth, held by the Umfravilles, the Bertrams and the Merlais, extended in a belt across the district. North of them the Vesci, lords of Alnwick, built their castle on the banks of the Aln, and laid the foundation of the second Northumbrian town. The land was again committed to the care of a Norman earl; but it would seem that the lawlessness of the Northumbrians was contagious. Earl Mowbray plotted against William Rufus, who took the castle of Tynemouth, but was foiled by the strength of the rock of Bamborough, which could not be taken till Mowbray’s imprudence made him the victim of a stratagem. After this we hear no more of official earls. Northumberland depended directly on the crown, and went its own way for a short time in peace. But the weakness of Stephen had well-nigh allowed Northumberland to go the way of Lothian and become attached as an appanage to the Scottish crown. David I. had married the daughter of Earl Waltheof, and Stephen recognised this claim to the earldom of Northumberland. If Stephen had had a less statesmanlike successor than Henry II. the English Border might have been fixed along the old frontier of the Roman Wall. But Henry II. regarded it as his first duty to undo the mischief of Stephen’s reign. He demanded the restoration of the northern counties, and from this time the limits of the English Border were definitely settled. It is true that there was a small piece of land on the Cumbrian Border about the possession of which England and Scotland could not agree, and this Debatable Land was occupied as common pasture by the inhabitants of both countries from sunrising to sunsetting, on the understanding that anything left there over night should be fair booty to the finder. On the Northumbrian Border also, the fortress of Berwick was an object of contention and often changed hands, till the luckless town of Berwick-upon-Tweed received the doubtful privilege of ranking as a neutral state, and its “liberties” were exposed to the indiscriminate ravages of English and Scots alike. Nor should it be unnoticed that the castle of Roxburgh was generally in the hands of the English king, as a protection of the strip of low-lying land south of the Tweed, where the barrier of the Cheviots merged into the river valley.

I have now traced the historical steps in the formation of the English Border, and the causes which gave the modern county of Northumberland a separate existence and a distinct character. The rest of its history is written on the county itself, and tells its own story in the various interesting remains of antiquity which cover the land. I will briefly draw attention to the chief periods which they mark.

(1) From the beginning of the twelfth to the beginning of the fourteenth centuries, baronial and monastic civilisation did much to bring back order and prosperity. The details of the management of a Northumbrian farm have been preserved in the compotus of the sheriff of Northumberland, who held for six months the lands of the Knights Templars at Temple Thornton, which were seized by Edward II. in 1308. The sheriff’s accounts are compiled with business-like precision, and enable us to judge with accuracy of Northumbrian farming at the time. They show a system of farming quite as advanced as that which existed at the end of the last century. For instance, among the expenditure is an entry for ointment to protect the heads of the sheep from the fly. The total receipts were £94 2s. 7d., the total expenses were £33 10s. 7d., leaving a balance of £60 12s., a proportionate return for his expenditure which any modern farmer would be glad to obtain.

(2) This period of prosperity was already passing away when the sheriff penned his accounts. He had to sell some oats and barley in a hurry, propter metum Scotorum superveniencium—through dread of a raid of the Scots. The Scottish war of Edward I. led to the ruin of the English Border. The nova taxatio of the goods of the clergy, made in 1318, estimates the ecclesiastical revenues in the Archdeaconry of Northumberland at £28 6s. 8d. for the benefices of Newcastle, Tynemouth, Newburn, Benton, Ovingham and Woodhorn. Then follows an entry that all the other benefices are vasta et destructa, et in eisdem nulla bona sunt inventa—are barren and waste, and no goods are found in them. For the northern part of the county there is an enumeration of the benefices, with the remark that they are vastata et penitus destructa—wasted and wholly destroyed. It was this state of things which led to the organisation of border defences. The office of Lord Warden of the Marches, established under Edward I, became a post of serious responsibility. Castles which had been built to overawe a turbulent population, or to increase the power of their owners against the crown, became necessary means of protection to the country. The land was dotted with peel towers—small square rooms of massive stones, strong enough to give temporary refuge to fugitives till the marauding troop had passed by on its plundering raid. Elsewhere were earthen or wooden huts, which contained nothing that could attract cupidity. An Italian traveller, Æneas Sylvius Piccolomini, has left a picture of a journey through Northumberland in 1435. The folk had poultry, but neither bread nor wine; white bread was unknown among them. At nightfall all the men retired to a peel tower in the neighbourhood, through fear of the Scots, but left the women behind, saying they would not be harmed. Æneas sat in terror round the watch-fire till sleep overcame him, and he lay down on a couch of straw in one of the huts. His slumbers were disturbed by the cows and goats, who shared the room with the family and nibbled at his bed. At midnight there was an alarm that the Scots were coming, and the women fled to hide themselves. The alarm, however, was groundless, and next day Æneas continued his journey safely. When he reached Newcastle he seemed to himself again to be in a world which he knew. For Northumberland, he says, “was uninhabitable, horrible, uncultivated”.

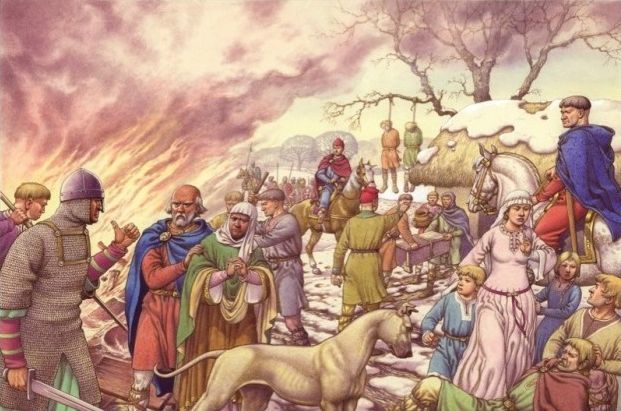

(3) The more pacific attitude towards Scotland adopted by Henry VII brought a little peace; but the battle of Flodden Field and the events that followed led to a determination on the part of Henry VIII to use Border raids as a means for punishing Scotland, and gradually wearing out its strength. The Lords Wardens are urged on to the work of devastation by the Lords of the King’s Council, and send in hideous accounts of their zeal in this barbarous work. Thomas Lord Dacre writes with pride that the land, which was tilled by 550 ploughs, owing to his praiseworthy activity “lies all waste now, and no corne saune upon none of the said grounds”. Again, he tells Wolsey how the lieutenant of the middle marches entered Scotland with 1,000 men and “did very well, brought away 800 nowte, and many horses. My son and brother made at the same time an inroad into the west marches, and got nigh 1,000 nowte. Little left upon the frontiers except old houses, whereof the thak and coverings are taken away so that they cannot be brent.” The records of Border warfare throw light upon the cold-blooded and deliberate savagery which characterised the beginning of the sixteenth century. We recognise it clearly enough in other countries: we tend to pass it over leniently at home.

(4) Under Elizabeth came peace between England and Scotland, and things grew better on the Borders. Deeds of violence were still common and disputes were rife. But Elizabeth’s ministers were anxious that these disputes should be decided by lawful means, and that disorders should be as much as possible repressed. An elaborate system of international relationships was established. Every treaty and agreement about the government of the Borders was hunted up and its provisions were put in force. The wardenship of the English Marches was no longer committed to Percies, Greys, or Dacres, but to new men chosen for official capacity. There was no longer need of Border chiefs to summon their men for a foray and work wild vengeance for wrongs inflicted. Aspiring statesmen like Sir Ralph Sadler and Sir Robert Carey were entrusted with the task of organising a system of defence. Scotland was overawed not so much by armed force as by red-tape. The Scottish Council was employed in answering pleas and counterbleas wherewith the technical ingenuity of the English wardens constantly plied them. The amount of ink shed over the raid of Reedswire is a forecast of the pest traditions of modern diplomacy. Scotland was pestered by official ingenuity into a serious consideration of Border affairs. The English Borders were elaborately organised for defence. The country was mapped out into watches, and the obligation was laid upon the townships to set and keep the watches day and night. When the fray was raised, every man was bound to follow under penalty of fine and imprisonment. Castles and peel towers were converted into a system extending across the Border, with signal communication from one to another. A brief quotation from some articles made at Alnwick in 1570 may serve to illustrate the thoroughness of the system: “That every man that hath a castelle or a tower of stone shall, upon every fray raised in the night, give warning to the contrey by fier in the toppe of the castelle or tower, in such sorte as he shall be directed from his warninge castelle, upon paine of iijs. iiijd.”

The system in itself was admirable. Its only defect was that in proportion as it led to momentary success it tended to decay. Sir John Forster writes from Berwick in 1575: “Thanks be to God we have had so longe peace that the inhabitants here fall to tillage of grounde, so that theye have not delight to be in horse and armore as they have when the worlde ys troblesome. And that which theye were wont to bestowe in horse they nowe bestowe in cattell otherwayes, yet notwithstandinge whensoever the worlde graveth anye thinge troblesome or unquiet theye will bestowe all they have rather than theye will want horses.” It is worth while noticing Sir John Forster’s remedy for the carelessness which peace engendered. He advises that “a generall comaundement should come from her majestie to the noble men and gentlemen here to favor their tennants as their auncestors have doon before tyme for defence of the frontiers.”

“To favor their tennants as their auncestors have doon before tyme.” I believe that in these words we have the key to much of the social history of the English Border. A ramble through Northumberland shows much that tells of the former greatness of feudal lords. There are no corresponding memorials to distinguish the sites of the townships, which once largely consisted of freeholders, who armed themselves and fought for house and home. Northumberland at the present day is regarded as a great feudal county, with feudal antiquities and feudal memories visible at every turn. I believe, on the contrary, that in no part of England did the manorial system sit so lightly, or work such little change. Traces of primitive institutions and primitive tenures are found in abundance whenever we penetrate beneath the surface.

First of all, there is a noticeable feature which especially marks the district comprised within the limits of the old Northumbrian kingdom-the survival to the present day of a very large number of townships, which are still recognised as poor-law parishes, and elect their own waywardens, overseers and guardians of the poor. Even at the present day there are only thirty ecclesiastical parishes in this county which are conterminous with a single township. The remaining 132 parishes contain among them 513 townships. There are as many as thirty townships contained in a single parish, and the general number is four or five. This can easily be accounted for from the facts of local history; but it shows the need which was felt for the maintenance of small separate districts with some powers of self-government. Again, the ecclesiastical vestries of the ancient parishes of Northumberland consist, almost universally, of a body of four-and-twenty, who are appointed by co-optation. The term “vestry” does not occur in the Church books, which uniformly speak of a “meeting of the Four-and-twenty”. This seems to point to an original delegation of power into the hands of representatives from the different townships comprising the parish.

These townships were village communities each an agrarian unit. I will not attempt to co-ordinate my evidence about them with any general theory of land tenure, but will simply state a few facts relating to them. The township of Embleton lies within the barony granted to John Vesconte by Henry I. A deed, dated 1730, at which time the Earl of Tankerville was lord of the manor, contains the award of arbitrators appointed by the consent of all parties to have the lands of the townships divided. It recites that the Earl of Tankerville and eight others are “severally seized of the farms, cottages, and parts of farms in the township fields,” Lord Tankerville of sixteen and a half farms, the others of quantities varying from three farms, one and eleven-twelfths of a farm, to one-sixth part of a farm. It then proceeds: “The premises above mentioned lie promiscuous in common fields undivided “. The only holder in severalty was the vicar, whose “parcel of ground known as the East Field” affords the only known landmark from which the division can begin. The general result of the arbitrarors’ award is that the vicar receives an average of fifty-six acres for each of his three farms, Lord Tankerville gets an average of sixty-four acres for each of his sixteen and a half farms, and the other holders average seventysix acres for each of their eight farms. The varying quantity seems to depend on the quality of the land allotted in each case. I will not multiply evidence for this opinion, but will quote a statement made by a man who was in the employment of a solicitor in Morpeth, and who represented a legal memory extending back as far as 1780. He says: “I believe that in former times the word farm was used in many parts of this country to express an aliquot part in value of a township, being one of several portions of land of which a township consisted, each one of such portions having originally been of equal value”. He supports this by reference to cases of allotments in which he was himself concerned.

This use of the word farm to signify an original unit of land tenure is peculiar to Northumberland, and probably has led to much interesting evidence being overlooked, as the ancient use of the word for a fixed interest in undivided land is easily confounded with its modern signification of a fixed amount of land. But many traces can still be found by one who searches for them. The records of vestry books show that contributions to parochial purposes were assessed upon each township in proportion to the number of ancient farms which it contained. In many cases this continued long after the division of the lands of the township, and long after the old meaning of the word farm had been forgotten. Church rates were paid on farms; so were customary payments to the parish clerk and sexton. At Warkworth the vestry resolved to rebuild the church wall, each farm being responsible for two yards of walling. It is curious to observe how long it was possible for an ancient institution to exist side by side with a new one. In the township of North Seaton the assessment of church rates on farms ceased in 1746, but the assessment of poor rate remained on the ancient basis down to 1831. Still more noticeable is the case of the township of Burradon. I have no record when the enclosure of the greater part of the township took place; but two parcels of land were left unenclosed. One was divided in 1723, the other in 1773. Upon both divisions each freeholder had appointed to him a part of the common in proportion to the number of ancient farms of which his enclosed lands were reputed to have consisted. Even after this final division the old system did not entirely disappear. Up to the year 1827 poor rates and highway rates were assessed at so much per farm, not so much per pound.

The evidence which I have at present proves the ancient division into farms of forty-eight townships. A calculation of the areas of these farms, after they were divided, shows a great variety. They range from 1,083 acres to fifty. No doubt this can easily be accounted for. In the less fertile parts of the county there were large tracts of waste, which ultimately were absorbed by the townships, scattered at a considerable distance from one another. But there are eight townships where the average farm is below 100 acres, nine townships where the average is between 100 and 120 acres, and nine where it is between 120 and 150 acres.

This great variety renders it difficult to account for the Northumbrian farms by any of the modes of reckoning which have hitherto been proposed as of universal application. The Northumbrian unit seems to point solely to the actual facts of the needs of each township at the time of its original settlement.

The relations of these townships to the feudal lords varied, I believe, as much as did their unit of land tenure, though on this point it would be necessary to search the manor rolls in the case of each one separately. A few facts, however, may be stated on this subject. The manor of Tynemouth consists of eleven townships. Three of them are of freehold tenure. The remaining eight were in 1847 held partly in copyhold, partly in freehold. Each copyhold farm made a payment for “boon days,” and also paid a corn rent. This rent varied in each township; but payment was in every case made according to the number of ancient reputed farms or parts of a farm of which the land consisted. We have no difficulty here in tracing a case in which the lord’s demesne was scattered in eight out of the eleven townships contained in his manor. Three townships belonged entirely to freeholders, and freeholders were settled in the other townships also.

I pass to another instance, the township of North Middleton. The rolls of the court baron of the barony of Morpeth, which is held by the Earl of Carlisle, show that transfers of land in that township were accomplished by the admission of the new owner on the rolls of the manor. The township of North Middleton consisted in 1759 of fourteen farms, of which ten were held by the Duke of Portland, one by the Earl of Carlisle, and three were divided among six other freeholders. The condition of the township in 1797 is described as follows: “The cesses and taxes of the township are paid by the occupiers in proportion to the number of farms or parts of farms by them occupied. These farms are not divided or set out, the whole township lying in common and undivided, except that the Duke of Portland has a distinct property in the mill and about ten acres of land adjoining, and that each proprietor has a distinct property in particular houses, cottages and crofts in the village of North Middleton. The general rule of cultivating and managing the lands within the township has been for the proprietors or their tenants to meet together and determine how much or what particular parts of the land shall be in tillage, how much and what parts in meadow, and how much and what parts in pasture; and they then divide and set out the tillage and meadow lands amongst themselves in proportion to the number of farms or parts of farms which they are respectively entitled to. And the pasture lands are stinted in proportion of twenty stints to each farm.”

In this case we have the open field system, with separate homesteads. The lord has a small share in the common lands, but has no separate demesne. The freeholders have mostly parted with their interests to a wealthy landholder; those who still remain hold small portions varying from seven-eighths to three-eighths of an original farm.

A third instance shows other results. The township of Newbiggin-by-the-Sea was in a manor which ultimately passed into the hands of the Widdringtons.

In 1720 Lord Widdrington’s lands were forfeited and were sold to a London company, who claimed manorial rights which the freeholders of Newbiggin would not allow. The proceedings of a long Chancery suit, in which the freeholders were left with their privileges unimpaired, show us a community completely self-governed, with no interference from a lord and little from the crown. They had a grant of market and fair, and tolls on ships coming into their little harbour. They paid to the crown a fee-farm rent of £10 6s. In 1730, to which date the freeholders’ books have survived, we find the arable land already divided, but the pasture land still in common. The freeholders meet and make bye-laws for the pasturage. They appoint constables, ale-tasters, and bread-weighers. They levy tolls on boats and ships, and receive payments for carts loading sea-weed from the shore, for lobster tanks in the rocks, for stones quarried on the fore-shore. The money received from these rents of the rocks is divided among the freeholders in proportion to the ancient freeledges, or farms.

These three instances may serve to show the exceeding variety of social life in Northumberland, and the comparatively slight effects of the imposition of the Norman manorial system upon the ancient townships. No doubt this great variety was due to the exceptional character of the county. The lords were bound to “favour their tenants for the defence of the frontiers”. They meddled little with the freeholders of the townships, who formed a stalwart body of soldiers ready to follow the fray.

(5) But this same habit of following the fray had its disadvantages. It created a wild and lawless manner of life. Though war ceased between England and Scotland, feuds and robberies by no means ceased between the borderers on each side. “The number is wonderful,” write the English commissioners in 1596, “of horrible murders and maymes, besides insupportable losses by burglaryes and robberies, able to make any Christian eares to tingle and all true English hartes to bleede.” They estimate the murders at 1,000 and the thefts to the value of £100,000 in the last nine years. The union of the crowns of England and Scotland under one sovereign swept away all pretence for hostility on the Borders, and left the problem of reducing a lawless people to order. This work was begun by the strong sense and capacity of Lord William Howard of Naworth. It would be an interesting and profitable study to trace exactly the disappearance of savage ways and riotous tempers. The work has, at all events, been done in a thorough and satisfactory manner. In no part of England can there be found a more orderly, peaceable, law-abiding folk than are the Northumbrian peasantry. In no part of England is greater friendliness and hospitality shown to the wayfarer than in the valleys of the Cheviot Hills, which were once the haunts of moss-troopers. I never wander over the lovely moorland, and look upon the smiling, peaceful fields below, without feeling comfort amid the perplexities of the present by the thoughts of the triumph of the past. The frowning castles of the feudal lords now stand embowered in trees, and tell of nothing save acts of friendliness to those who dwell around. The peel towers in their ruins defend the flocks and herds from nothing save the inclemency of the heavens. Goodly farm-houses and substantial cottages for the peasants betoken prosperity and comfort. The sturdy good sense of English heads, the enduring strength of English institutions, have solved a problem in this Border-land at least as difficult as those which trouble us in the present and cast a shadow over the future.