Editor’s note: The following is extracted from A History of the Middle Ages, by Dana Carleton Munro (published 1902).

During the early middle ages teaching was done wholly by the clergy. In some of the towns and villages there were elementary schools taught by the parish priests. In the monasteries and cities there were schools, both elementary and advanced, under the charge of the abbots or bishops. Whatever learning there was north of the Alps was due to the labors of the Church.

It was formerly the custom to refer to the middle ages as the dark ages. From their own ignorance of the facts historians had thought that the medieval world was entirely steeped in ignorance and barbarism, that there was no learning even among the churchmen, and that all society was in a state of chaos. Now that the facts are known, the term “dark ages” has been abandoned, or, if used, is applied only to the time between the breaking up of the Roman Empire and the eleventh century or, still more narrowly, to the period of the invasions in the ninth and tenth centuries. In the history of education in Christian Europe the latter was the darkest age. Charles the Great had been anxious to educate his subjects, and under his rule schools had been established in many monasteries and towns. Italian, English, and Scotch, as well as native scholars, were induced to become the teachers of the Franks. During the period of the invasions learning was maintained only in a few favorable localities. In the latter years of the tenth century, especially in Germany, there was a reawakening, and teaching in the monastery schools became more common. The influence of Cluny was very important. From this time greater attention was given to learning, and the schools increased in number and improved in quality.

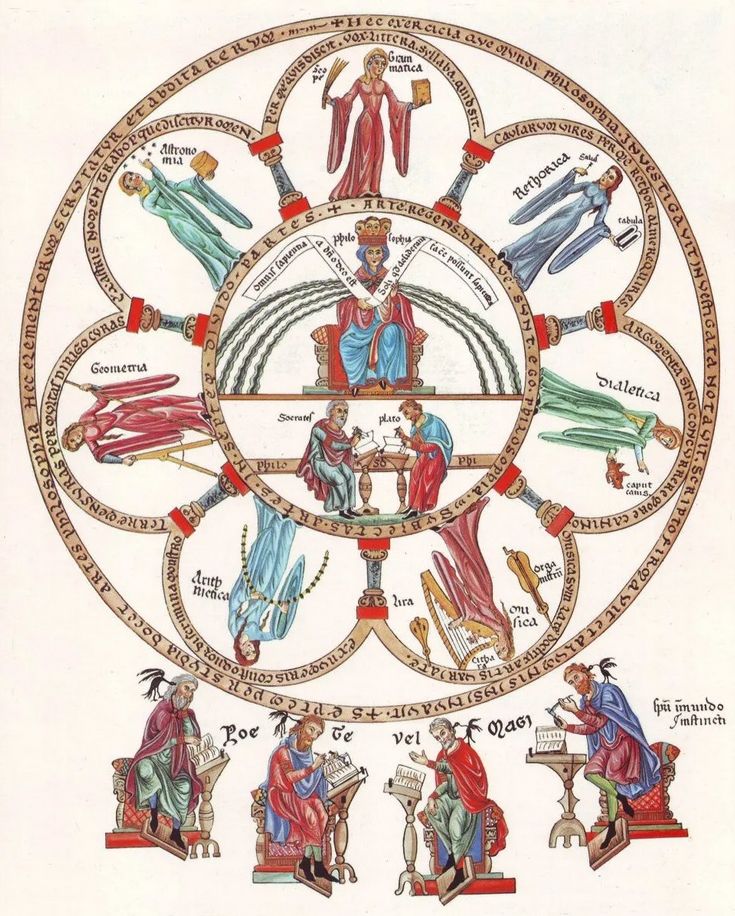

Education was intended wholly for the service of the Church, and most of the students became members of the secular or regular clergy. This determined to a very great extent the character of the teaching. During the early middle ages all the studies were included in the “seven liberal arts” and theology. First came the trivium, or threefold way: grammar, rhetoric, and dialectics, or logic; then the quadrivium: arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy. The trivium and quadrivium together made up the seven liberal arts.

These studies were not taken up in any regular order, and the names of the various subjects do not indicate their contents. Grammar, for example, included the study of the Latin classics, with an explanation of their historical and mythological allusions. Under the subjects of the quadrivium were grouped all the fragments of knowledge concerning the natural sciences. Theology was the most important branch, and the study of the seven liberal arts was pursued partly as a preparation for the correct understanding of the Holy Scriptures and the writings of the church fathers.

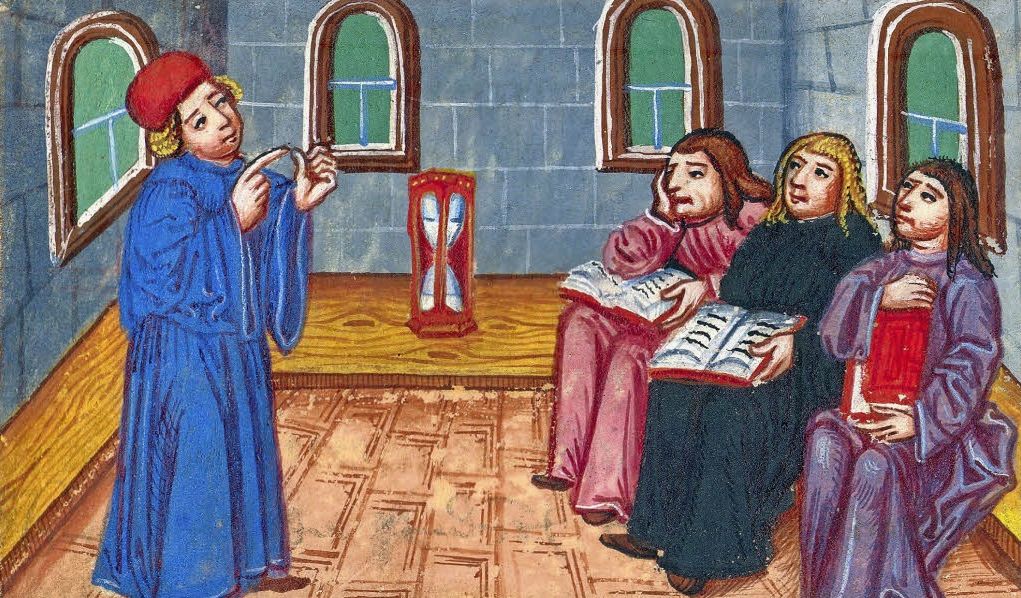

The teachers read the text-books to the pupils, who had none, and who were expected to commit everything to memory. When a scholar failed he was flogged; fortunately for his comfort, he was not expected to learn a great deal. In arithmetic the students were taught to keep simple accounts; in music, what was necessary for the church services; in geometry, a few problems; in astronomy, enough to calculate the date of Easter. It was not until the twelfth and thirteenth centuries that these subjects were really studied seriously. Before that, when a boy had obtained a smattering of grammar and the quadrivium, he devoted himself, if he wished to study more, to theology or dialectics. Frequently he would travel from place to place to hear the most famous teachers. In the early part of the twelfth century the brilliant teaching of Abelard attracted to Paris students from all the European countries. He had broken away from the traditions of the students of the tenth and eleventh centuries, who were apt to accept everything written as necessarily true, and insisted upon questioning the correctness of the information handed down by the earlier writers. This point of view was novel, and attracted auditors by hundreds. The pleasant life in the wealthy capital of France contributed greatly in drawing students from other parts of that country, and from Germany, England, and the northern lands. From this time Paris became the chief center of learning for all Europe. In the thirteenth century it was said that “France is the hearth where the intellectual bread of the whole world is baked.”

Teachers also were attracted to the place where students congregated, for a teacher’s income was derived from the fees paid by the pupils who chose to listen to him. The masters and students who were foreigners were obliged to band together for mutual protection and support, as they were not citizens, and consequently without the protection of the laws. In the frequent rows between students and citizens the former would naturally support one another. The king was very glad to have the scholars there on account of the added wealth which they brought to the capital, and because of the prestige which the great school conferred upon Paris. Consequently, when a serious fight occurred, in which five students were killed by the king’s police and the students threatened to leave Paris in consequence, the king offered them special privileges if they would remain. It was in the year 1200, and this may be considered the date for the official recognition of the University of Paris, although there had been schools in existence for many years, and the university was never founded in the modern sense.

The word university was originally a collective term, and was applied indifferently to a learned corporation, a guild of artisans, a band of soldiers, or any other body of men. The restriction of it to a particular institution was an accident. What we call a university was called in the thirteenth century a studium, or studium generale; the addition of generale meant that students from different countries were in attendance. A studium generale might or might not include schools of law, medicine, and theology; generally, there was at least one of these schools in addition to the faculty of arts. Sometimes the teachers or masters controlled the studium, as at Paris; sometimes the students were the governing body, as at Bologna, where they made regulations as to what studies should be taught, how fast the masters should lecture, and what the latter should wear.

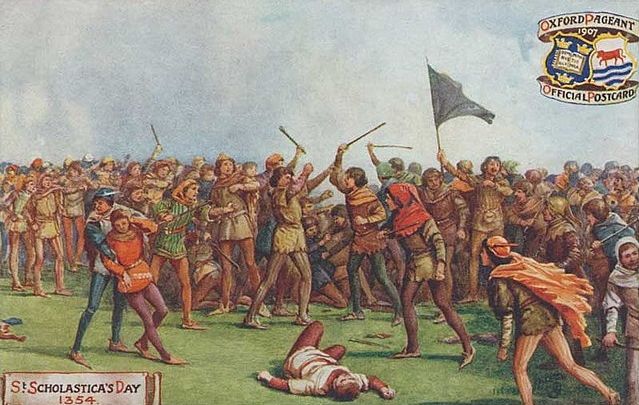

The scholars were chiefly a body of men from places outside of Paris, bound together by common interests, who would remain only as long as they found Paris attractive. Furthermore, they were either already members of the clergy or intended to become members later.[1] These facts determined the character of the privileges granted to the students. The king, in 1200, guaranteed safe-conduct for them in traveling, and for the messengers who carried their letters and brought their supplies; he exempted them from trial in the royal courts or imprisonment in the royal prison, and gave them the privilege of being tried only by the ecclesiastical courts. But the most important of all the privileges was the “right of migration.” The university held no property; the lectures were delivered in hired buildings, so that it was very easy for the whole body of masters and students to decamp at a moment’s notice. This they did frequently and on the slightest provocation. On the other hand, it was highly advantageous to a city to possess a studium generale. It was not only a cause of prestige but also a very considerable source of income. The universities realized their advantage, and exercised their right of suspending lectures to enforce their privileges. The course of events was usually the same. The students became involved in a riot, of which they were commonly the cause; the police were called out; some students were wounded or killed; the university decreed a cessation of lectures and threatened a migration. If their demands for redress were not promptly complied with they left the city. The final result in most cases was a full compliance with the students’ demands, and frequently a payment of money or a grant of greater privileges to them. Probably, in a majority of cases, the scholars were the aggressors, but came out triumphant. Between 1188 and 1338, inclusive, twelve cessations and migrations from Bologna are recorded, and these resulted in the foundation of eight “permanent Studia Generalia” in other places. In fact, a migration was the most usual cause of the foundation of a new university.

Foreigners, who were natives of the same province, naturally associated together, and formed a club for social intercourse and self-protection, just as Americans studying in Europe do now. Gradually these associations became more formal, and spread until all the students were enrolled in the membership of some province. Provinces were grouped together into nations. Each of these had its own officers, money-chest, and seal. Likewise the students and teachers of the same subjects naturally came together, and so the faculties of arts, medicine, law, and theology grew up. Each university had this twofold organization of faculties and nations; in some places, as has been said, the masters controlled these organizations; in others, the students. The faculty of arts was usually the most numerous and the most important.

The University of Paris was modeled on the guilds. The masters, who had the right to teach, corresponded to the master-workmen; the students corresponded to the apprentices. As the latter had to work for a term of years and to prove their fitness before they became members of the guild, so the students must study for six years and pass an examination before they became masters in art. In theology, they had to study eight to fourteen years before they became masters. The scholars were of all ages, from boys of twelve to old men. The studies were extremely varied, “as the students always desired to hear something new.” The required course for the degree of master of arts was composed of only a few subjects, and did not take all of a student’s time for six years. Many who attended the universities never took a degree at all. Consequently there were always some desirous of taking subjects not included in the required course. Mathematics and the natural sciences attracted many students. The study of the classics was almost entirely abandoned at Paris in the thirteenth century.

In the early monastic schools the pupils had not been required to pay for their tuition, and as long as the teaching remained in the hands of the monks this continued to be the custom. But when masters began to earn their living by teaching, the students were required to pay. Some of the latter were so poor that they had to beg for their living. To provide for such, colleges were founded at the different universities. At first these were merely endowed lodging-houses, under the supervision of a resident master. Gradually it became the custom for the master to give instruction to the other residents, until the colleges became the principal centers for teaching. Paris was the great home of the college system, and from there it spread under a somewhat changed form to the English and other universities; much later the colleges in this country were patterned after the English models.

In the thirteenth century Paris was the chief university north of the Alps, and was noted especially for its faculties of arts and theology. In Bologna, Italy, where a studium generale had grown up somewhat earlier than at Paris, law was the most prominent branch, and the city was thronged with students from all the European countries. The University of Oxford, although in existence earlier, became large and important only after 1229. Then, in consequence of a town and gown row, in which several of the students had been killed, the masters and scholars withdrew from Paris, and many of them went to Oxford, because the king of England had offered special inducements. In the same century other universities were founded in Italy, France, Spain, and England. The earliest ones in Germany date from the fourteenth century. The number of students at the leading universities in the thirteenth century was very large; Paris and Bologna may have had 6,000 to 7,000 at the time of their greatest prosperity; Oxford 1,500 to 3,000.

The majority were boys in their teens or young men, who enjoyed special privileges and were under no restraint. Drinking was a universal habit. Under these conditions it is no wonder that many led a disorderly life, and that in an age when fighting was such a common amusement rows were very frequent. The rich nobles brought armed retainers with them, and sometimes fights arose between the members of different nations. The amusements, also, were of a very rough form, characteristic of the age. Yet in the universities there was an intellectual life, a zest for knowledge which led to a rapid advance. Earnest scholars, like Roger Bacon, were investigating new fields and laying the foundations for the wonderful age which was to follow.

________________________________________

[1] It is said that twenty of Abelard’s pupils became cardinals, and more than fifty, bishops.

Great bit of background history!

“The majority were boys in their teens or young men, who enjoyed special privileges and were under no restraint. Drinking was a universal habit. Under these conditions it is no wonder that many led a disorderly life, and that in an age when fighting was such a common amusement rows were very frequent. The rich nobles brought armed retainers with them, and sometimes fights arose between the members of different nations. The amusements, also, were of a very rough form, characteristic of the age.”

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.