.

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Historical Studies, by John Richard Green (published 1903).

I

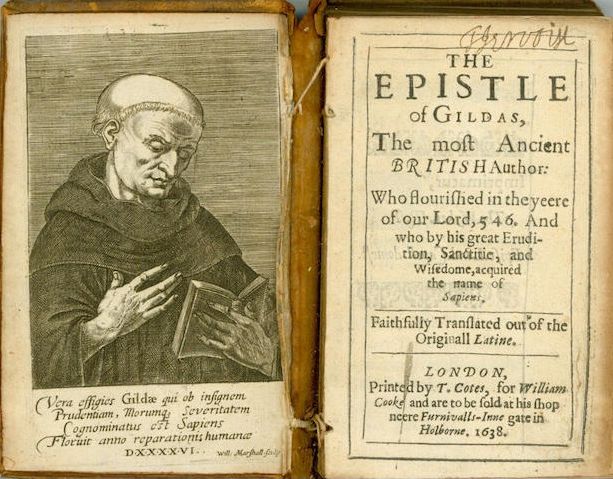

It is not the least among the many merits of Dr. Guest, in his treatment of our earliest history, that he has had the courage to acknowledge the merits of Gildas. Few contemporary writers have been visited with equal severity by later historians; even those who, like Dr. Lappenberg, set aside the absurd doubts thrown recently on his authenticity, lavish their censures on his ignorance of the Roman rule, his rhetorical exaggeration, and the provoking haziness of his description of the Great Conquest, which from its title would seem to form the theme of his book. It is difficult, indeed, not to feel some disappointment when we compare Gildas with the contemporary Provincial who has preserved for us the annals of the Conquest of Gaul. In Gregory of Tours the old world jostles roughly with the new, but in the very confusion and disorder of the time. The weak, clever subtlety of the Roman, the fierce childish passion of the Frank, the crash of the old administration before the irresistible march of the conqueror, the concentration of all moral life and energy in the Church before which he bowed, form the bold outlines of a picture which finds no parallel in the liber querulus of Gildas. But, in truth, the historic value of Gildas lies in the contrast between the two works. The Bishop of Tours is the representative of a new France which has sprung out of conquered Gaul. He owns the barbarian as his master. He describes his marches, his victories, his murders, his greed, with a subject’s interest. The bitterness of the Conquest is already past. The fusion of the two races has already begun. The tongue and the laws of the Provincial not only remain his own, they are threatening to become those of the Frank. The religion of Rome has superseded the faith of Woden and of Thor. There is a confusion of peoples and languages and ideas in Gregory’s work, as picturesque and as significant as the confusion of the consular insignia with the Teutonic axe in Chlodewig “the Patrician.” But no British neck had bowed before the English invader, no British pen was to record the conquests of Hengist or of Cerdic. Slowly, stubbornly, the Provincial of Britain had retreated before the sword of the conqueror, but across the burnt and harried border of the two races the Englishman remained as strange to him as he had been in his Schleswig homeland. To Gildas, a century after their landing, his foes are still “ferocissimi illi Saxones, Deo hominibusque invisi,”[1] “dogs,” “barbarians,” “wolves,” “whelps from the kennel of barbarism.” Their victories are victories of the powers of evil, chastisements of a divine justice for national sin. Their ravage, terrible as it was, was all but at an end; in a century more, so old prophecies told, their very hold on the land would be shaken off. The prophecy is the first outbreak of that undying hope of the Celt that survived through ages of slavery and death. But of submission to the invader, of intercourse with the barbarian, there is not a word. We hear nothing of their fortunes or of their leaders. Across the border Gildas gives us but a glimpse—doubtless he had but a glimpse himself—of “forsaken walls,” of shrines polluted by heathen impiety.[2] Such a silence is of course disappointing enough to the children of the conquerors, eager to learn something of the deeds of those fathers who made the land their own. But in itself it is of the highest historical significance. It is just because Gregory could write the story of Chlodewig or Fredegonde that the temper, the tongue, the laws of his own Gallic province have superseded the temper, the tongue, the laws of the Frank. It is because Gildas, like his race, met his conquerors with nothing but defiance, that the tongue and the law, not of Gildas, but of those conquerors, remained the tongue and the law of after Englishmen.

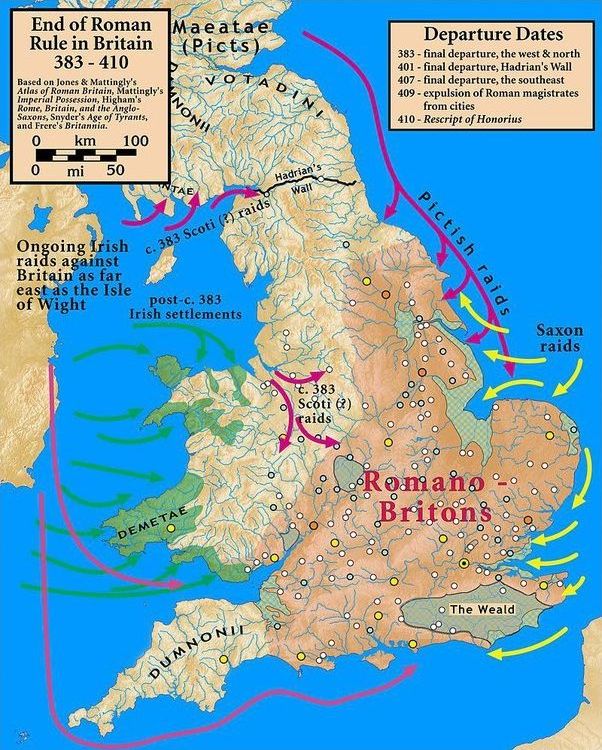

Hardly less historical significance is to be found in the strange tone which Gildas adopts towards his own countrymen in the strange caricature which he gives of their history. Certainly all trace of authentic tradition has disappeared when the Roman wall and the fortresses of the Saxon shore are represented as parting gifts of a benevolent Empire to its unworthy subjects, when the trembling Britons are pictured as being dragged from the wall by the hooked weapons of the Picts. But, in fact, nothing shows better the tremendous rift made by the English Conquest in the traditions of Britain than this strange sketch of the history that preceded it. The very promise to give some account of Imperial Britain is qualified by a quantum potuero.[3] What he does give comes, he tells us plainly, “not so much from native writings or written memorials, for if any such existed they have been burnt or carried off by those who have fled into exile—at any rate they are not to be found as from accounts brought over sea (transmarina relatione) which frequent interruption of intercourse leaves obscure.” In this disappearance of all authentic history, the past took its colour from the very misery which Gildas saw around him. ruin, the defeat, the feud and bloodshed of the wrecked Province were contrasted with the golden age of a fancied past. Rome became all the dearer as she faded into the distance. Men still clung, as Gildas clings after a century of severance, to the tone of the Provincial. In them, as in him, the Empire had become a religion; it could not err. The very sufferings of the deserted provinces are their crime. The one chance of preservation in the midst of chaos is to cling to the relics that are left of the old “Ordo” of the Roman rule. If in the traditions of the Conquest we are to see, with Dr. Guest, the contest of a Roman with a British party in the first struggle with the Jute, we must look for the words of Gildas to recall for us the temper of the Provincials under Ambrosius and to enable us to realise by contrast something of the tone of Vortigern and their opponents. Of his British countrymen, of their “levity,” of their “ingratitude,” Gildas speaks as bitterly and as contemptuously as Swift would have spoken of the Irish under British rule. The first advent of the Imperial eagles seems to him like the arrival of some irresistible destiny, parendi leges, nullo obsistente, advexit.[4] When the Province revolts, it is a “treacherous beast”; when the legions hasten to subdue it, it is to wreak the Imperial vengeance on the “deceitful fox-cubs.” Over the panic of the Britons before the Roman attack he exults as an Orangeman might have exulted over the Irish panic at the Boyne: “Ita ut in proverbium et derisum longe lateque efferatur, quod non Britanni sunt in bello fortes nec in pace fideles.“[5] There is all the “ascendency tone” in his description of the rule which followed on the Roman Conquest; but not even an Ulster squire could have spoken with such a glow of triumph over the miseries of his fellow-countrymen as this Provincial. He reminds them of their serfage, of the whips that scored their backs, of the yoke that pressed down their necks, how the name of “Romania” had all but superseded that of Britain, how every coin and medal was stamped with the triumphant image of the Cæsar. In the actual politics of the Empire, Gildas is the most unflinching of legitimists; Maximus is a mere usurper, his accession a mere rebellion, his fall a just punishment for his impiety. The outburst is all the more significant if, as we rather gather from his own incidental phrases and from the Welsh traditions, the elevation of Maximus first re-aroused the hope of the conquered races. But with Gildas it is the “illegitimate tyranny” that brought about the ruin of Britain; the inroads of the Picts and Scots only gave him occasion for new insults over the “rebels,” for new eulogies of the Empire. He triumphs over the ruin of the Province, over her ignorance in arms, the humiliation of her appeal for aid, the despatch of her queruli legati to Aetius.[6] Rome, on the other hand, plays the part of the long-tried but forbearing Mother-Country, hurrying again and again to the rescue, scattering their foes, protecting them with fortresses, withdrawing indeed at last, but withdrawing with an Imperial dignity. It is, as we have said, a strange caricature, but it gives us faithfully enough the aspect which history took in the later Roman tradition, the story which would have reached us had the Empire won.

In the description which Gildas gives us of the period which intervenes between the earlier Pictish inroads and the coming of the English, we are at once on historic ground. Vague as the story is, it is very different from the merely ideal picture of the Empire which preceded it, and it has been ably vindicated of late in the researches of Mr. Skene. But for directly historical purposes the most valuable portion of the work lies undoubtedly in the three sections which give us the British tradition of the Conquest of Kent. With Dr. Guest we are “not ashamed to confess” that the story carries with it our “entire belief,” but the story must be read as it is written, and not according to the preconceived notions of readers. Taken—and it has very commonly been taken—as a general account of the Conquest of Britain, it is no doubt a mere piece of vapid rhetoric; but, not to dwell on the entire misconception of the nature and duration of that conquest which is involved in such an assumption, the notion itself is without the slightest countenance from the narrative as it stands. The story of Gildas is the simple story of the earlier war in Kent, the arrival of the Jutish chieftains at the summons of the Council of Britain, the disputes over their claims for pay and rations, the reciprocal threats which ended in war, the first terrible sally of the new settlers from Thanet, the revival of courage among the Britons, the victory which checked for a while the progress of the conquerors. It has hardly been noticed with what accuracy all technical terms are used throughout this narrative, and yet no better test of the authenticity of a work is to be found than in its use of technical terms. It is hardly possible that the forger of a later age could have known of that peculiar stage of the provincial government, which finds its only analogy in Gaul, but which a single phrase of Gildas sets simply before us, “Tum omnes consiliarii una cum superbo tyranno Gwyrthrigerno Britannorum duce caecantur.“[7] In the withdrawal of the directly Imperial rule the provincial council, which under it had only a consultative power, became necessarily the one source of authority, but the administrative titles, and doubtless the forms of administration, remained as before. How soon the sense of this was lost we see from the change of the “dux” in later versions of the story, into the king. The claims of the newcomers on their settlement in Thanet are described with the same technical colour, “impetrant sibi annonas dari,” and on the grant of these supplies in kind, “queruntur non affluenter sibi epimenia contribui.“[8] Threats followed complaints, and the “Eastern Fire” was soon blazing across the breadth of Kent “from sea to sea.” To Gildas, as to his contemporaries, the most terrible feature of the inroad was one which we are apt to forget—its heathen character. In striking contrast with what happened on the Continent, the sword of the invaders seems to have been especially directed against the clergy. They appear to have taken refuge in their churches, and to have rushed out as these were set on fire, to find death on the barbarian sword; no passage better illustrates the style and the historic value of Gildas :—

Ita ut cunctae columnae crebris arietibus, omnesque coloni cum praepositis ecclesiae, cum sacerdotibus et populo, mucronibus undique micantibus ac flammis crepitantibus simul solo sternerentur, et miserabili visu in medio platearum ima turrim edito cardine evulsarum, murorumque celsorum saxa, sacra altaria, cadaverum frustra, crustis semigelantibus purpurei cruoris tecta, velut in quodam horrendo torculari mixti, viderentur.[9]

For the moment the people were panic-stricken; some, overtaken in their flight, were butchered “in heaps”; some fled over sea; others, overcome by hunger, surrendered to become serfs of the conqueror. The passage is so valuable in its bearing on the question of the extermination of the Britons, that we quote the words: “Alii fame confecti accedente manus hostibus dabant in aevum servituri, si tamen non continuo trucidarentur, quod altissimae gratiae stabat in loco.“[10] We can hardly doubt that the terrible tale of massacre and exile is the same tale as that told by the English chronicler in the two meagre entries that commemorate the victories of Aylesford and Crayford. But no English record remains of the national reaction which, headed by the fugitives who had taken refuge among the cliffs of the Saxon shore, ‘from Richborough to Pevensey, soon in a decisive victory swept back the invaders to Thanet. It is here that the book abruptly breaks off. From that time to the great battle of Mount Badon victory wavered from the one side to the other; from that overthrow stretched a long period of peace.

II

The biographies of Gildas are so late and so untrustworthy that we are thrown back for information respecting him to the meagre notes of his life which his Epistle has preserved for us. The most definite of these fixes the date of his birth in the year of the battle of Mount Badon, some seventy years later than the landing of the English in Kent. The year was a year memorable in the annals of Britain. Wherever the great battle took place—whether, as Dr. Guest prefers, in the south, or, as we think Mr. Skene has made more probable, in the north of the island—it makes a distinct pause in the advance of the conquerors. London seems, after the first victories of Hengest, to have imprisoned the Jutes within the limits of Kent. The great Andreds weald served as a screen between Britain and the burnt and harried coast where the South-Sexe were settling down quietly as farmers around the ruined fortresses of the Saxon shore. After a quarter of a century’s advance, the terrible Gewissi had halted before the gigantic ramparts of Old Sarum. The great belt of woodland curving round from Dorset to the valley of Thames seemed finally to mark the halt of the southern assailants of the island; while the victories of Arthur, as we dimly read them in the fragment so oddly embedded in the Nennius,[11] had, for the hour at least, arrested the dissolution of the North. From London to the Firth of Forth, from the fens of Lincoln to St. David’s Head, the province still remained Britain. There was nothing in the long breathing space that followed Mount Badon to herald the second outburst of the English race, that terrible onslaught of forty years, from the victories of Ceawlin to the final overthrow of Chester, that really made Britain England. Between the two attacks stretched half a century of peace, and within this half century lies the life of Gildas. His very tone, indeed, is evidence how rudely the whole fabric of society had been shaken by the struggle which seemed at last at an end. It was not merely that the very tradition of the past had been swept from the mind of the Provincial, that for the confused memories which reached him he was indebted to sources “over sea,” to Brittany or to Ireland. It was that Britain had become isolated, that by the occupation of the coast the Province was cut off from all but occasional contact with the general life of the West. Not a trace of the wider culture of the Pagan world, little more than a trace of Christian literature, appears in the pages of the Epistle. Still peace, and with peace some sort of order, seemed at last to have returned. The imminence of the external danger had for the moment hushed the civil feuds which, far more than the sword of the Saxon, had strewn the fields of Britain with desolate cities. Civil and ecclesiastical society settled down again in seeming harmony for a period which, if we trust the vague expressions of Gildas, lasted through the first thirty years of his life. Then came the change which in half a century more had brought about the final ruin of Britain. Through the ten years from 550 to 560 all peace and order disappeared. The memory of peril from the stranger died with the generation that fought at Crayford and conquered at Mount Badon. Even the presence of the invader, felt more and more along the Eastern coast, where it seems clear that the district beyond the fens was about this time becoming East Anglia, and at least probable that the East Saxons were settling along the Colne and the Lea, passed almost unperceived by the Provincials. Their whole mind, in fact, was bent on the renewal of their ancient strife :—

Illis descendentibus cum successisset aetas tempestatis illius nescia, at praesentis tantum serenitatis et justitiae experta, ita cuncta veritatis et justitiae moderamina concussa et subversa sunt ut eorum non dicam vestigium sed ne dicam munimentum quidem in supradictis propemodum ordinibus appareat, exceptis paucis et valde paucis qui ob amissionem tantae multitudinis quae quotidie ruit ad Tartara tam brevis numeri habentur ut in eos quodam-modo venerabilis mater ecclesia in sinu suo recumbentes non videat quos solos veros filios habeat.[12]

It was, in fact, to this “venerable mother” that the disorder was above all attributable. The ecclesiastical aspect of Britain at this time finds its closest analogy in the later ecclesiastical history of Ireland. There, as Dr. Todd has ably pointed out in his monograph on St. Patrick, the Church organised itself on the basis of the clan; tribal quarrels and ecclesiastical controversies became inextricably confounded; no element of union was given as elsewhere by Christianity to the State, while a fatal hindrance to the exertion of all real spiritual influence was thrown in the way of the Church. In the confused strife which preceded the English invasion, the clergy had played a great political part, crowning and slaying kings, till the strife itself seems to. have taken something of a theological form. Whatever may be the exact import of the Pelagian controversies which are associated with the legend of St. David, or of the “Arian Plague” of which Gildas speaks, there was a far more fatal danger in the “apostasy,” the tendency to relapse into Paganism, which seems to have prevailed in the North. The victories of Arthur and the subsequent successes of Mælgwn saved Christianity for the time, but in the civil strife which had preceded them the moral tone of the British clergy had been hopelessly destroyed. As Giraldus found the Irish priesthood in the twelfth century, so Gildas saw the British priesthood in the sixth. There was the same strange medley of drunkenness with asceticism, of bitterest strife with self-devotion and saintliness. But Gildas is less inclined to dwell fairly on both sides than the amusing prelate of later years :—

Sed et ipse grex Domini ejusque pastores, qui exemplo esse omni plebi debuerant, ebrietate quam plurimi quasi vino madidi torpebant resoluti, et animositatum timore jurgiorum contentione, invidiae capacibus ungulis, indiscreto boni malique judicio carpebantur.[13]

Such as they were, however, the English invasion set them inevitably in the forefront of the race. The struggle in Britain was not merely a struggle of the barbarian with the Roman, it remained to the close a struggle of Pagan against Christian, and the hostility of the invader had been especially directed against the churches and the clergy. But though the terrible attack had increased their power, it seems to have done little for their character. The fierce invective of Gildas attacks their greed, their indolence, their neglect of spiritual duties, their indifference to the sin all round them, their contempt for sacred duty, their pride, their regard for the rich, their ambition of preferment. There is no reason for crediting this invective with exaggeration. The ecclesiastical aspect of Britain was that of a vast clerical body organised on a secular basis, and in the absence of those higher influences which intercommunion with a wider world could alone have given, dying down into a mere strife for power and wealth with the secular princes around them. The result of such a process in Ireland we know from the tittle-tattle of Gerald and the reforms of Malachi; that Britain was saved from lay Coarbs and episcopi vagantes, she owes to the sword which made Britain England.

The Teutonic Church which ultimately took its place can smile in its own steady instinct of order, in its regulated and decorous good sense, at the extravagances of the Church of the Celt. But it must be remembered that to the world at large the Celt has supplied an element of enthusiasm, of fire, of contagious sentiment, which it could never have gained from the decorum of the Teuton. It is just this fire, this dash, which quickens the turgid pages of the one writer whom the Church of Britain has bequeathed to us. Ascetic, keenly religious in the whole tone of his mind and temper, clinging with a fierce, contemptuous passion to the Roman tradition of the past, but vindicating as passionately the new moral truths with which Christianity fronted a world of license, steeped to the lips in biblical lore, orthodox with the traditional orthodoxy of the Celt, patriotic with the Celtic unreasoning hatred of the stranger, the voice of Gildas rings out like the bitter cry of one of those Hebrew prophets whose words he borrows, rebuking in the same tones of merciless denunciation the invader, the tyrant, and the priest. It is with a sort of relief that we turn from the historical opening of his Epistle to what some have called the “turgid rhetoric” of its close; the life of the Provincial brightens for us, as we see how the new moral force and freedom given by Christianity jostles with the political serfdom bequeathed by Rome. One after another of the petty chieftains under whom Britain was breaking down into its old chaos of disorder and misrule are branded with the same prophet-like severity. In actual morality they had sunk to the level of the savage: “All,” to use the words of their censor, “wallow in the same mire of parricide, fornication, robbery.” Perjured, bloodstained, unjust, their crimes were less base than the superstitious cowardice with which they strove to atone for them by heaping wealth on the clergy and the Church. It needed no prophet to foresee a judgment of God gathering for a nation whose rulers were such as these. In the half century that follows the cry of Gildas, the judgment had come. Already the east coast was lost. The English tribes which were destined to cluster around Mercia were soon winning midland Britain. Then came the irresistible advance of the West Saxons, severing the West Welsh from the main body of the British race, and rolling triumphantly along the north of Thames. Everywhere resistance seems to have been fragmentary and local-not national. So far as a national force existed, indeed, it was exhausting itself in the endless revolutions of the North. Among the princes whom Gildas has denounced, there is one whom he singles out as surpassing all in power and in the variety and enormity of his crimes. Mælgwn had begun with the murder of a royal uncle; then in a fit of wild remorse he had quitted the throne for a monastery; from the monastery he had burst again on the world, had driven away his wife, had murdered his nephew, and lived in adultery with his victim’s widow. But, vile as he was, Mælgwn seems to have been an able and a powerful leader. He had inherited the supremacy of those British princes of the Northern borders whose migration a hundred and fifty years before had wrested what we now call North Wales from the Gael; and a struggle, whose memory is preserved in a wild Welsh legend, had set him as chief over his fellow-kings. In a great battle north of Carlisle he again re-established Christianity in the Lowlands of the North, and massed the Celtic kingdoms together in the realm of Strathclyde. It was the last great victory of his race. The exhaustion caused by this distant struggle may have been the cause of the crowning success of Wessex, four years afterwards, at Deorham; the union of the Celtic power in the North seems only to have provoked the final effort of their English antagonists, and the establishment of the power of Northumbria on the field of Dægsastan. But with this closing phase of British history, Gildas has nothing to do. For the later, as for the earlier struggle, we are without a contemporary chronicler. What he does for us—and it is a service which has hardly been appreciated by later writers—is to paint fully and vividly the thought and feeling of Britain in the fifty years of peace which preceded her final overthrow.

_____________________________________________________________

[1] “the fierce and impious Saxons, a race hateful both to God and men”. Translated from the Latin by J. A. Giles, The Works of Gildas and Nennius (London: J. Bohn, 1841), 19.

[2] “I shall, therefore, omit those ancient errors common to all the nations of the earth, in which, before Christ came in the flesh, all mankind were bound; nor shall I enumerate those diabolical idols of my country, which almost surpassed in number those of Egypt, and of which we still see some mouldering away within or without the deserted temples, with stiff and deformed features as was customary.” Giles, 19.

[3] As much as I could. (ed.)

[4] “imposed submission upon our island without resistance.” Giles, The Works of Gildas and Nennius, 9.

[5] “So that it has become a proverb far and wide, that the Britons are neither brave in war, nor faithful in time of peace.” Giles, 9.

[6] “Again, therefore, the wretched remnant, sending to Ætius, a powerful Roman citizen, address him as follows :— ‘To Ætius, now Consul for the third time: the groans of the Britons.’ And again a little further, thus :— ‘The Barbarians drive us to the sea; the sea throws us back on the barbarians: thus two modes of death await us, we are either slain or drowned.’ The Romans, however, could not assist them…” Giles, 16.

[7] “Then all the councillors, together with that proud tyrant Gurthrigern, the British king, were so blinded…” Giles, 19.

[8] “The barbarians being thus introduced as soldiers into the island, to encounter, as they falsely said, any dangers in defence of their hospitable entertainers, obtain an allowance of provisions, which, for some time being plentifully bestowed, stopped their doggish mouths. Yet they complain that their monthly supplies are not furnished in sufficient abundance, and they industriously aggravate each occasion of quarrel, saying that unless more liberality is shown them, they will break the treaty and plunder the whole island.” Giles, 20.

[9] “So that all the columns were levelled with ground by the frequent strokes of the battering-ram, all the husbandmen routed, together with their bishops, priests, and people, while the sword gleamed, and the flames crackled around them on every side. Lamentable to behold, in the midst of the streets lay the tops of lofty towers, tumbled to the ground, stones of high walls, holy altars, fragments of human bodies, covered with livid clots of coagulated blood, looking as if they had been squeezed together in a press.” Giles, 21.

[10] “Others, constrained by famine, came and yielded themselves to be slaves for ever to their foes, running the risk of being instantly slain, which truly was the greatest favour that could be offered them.” Ibid.

[11] “Then it was, that the magnanimous Arthur, with all the kings and military force of Britain, fought against the Saxons. And though there were many more noble than himself, yet he was twelve times chosen their commander, and was as often conqueror. The first battle in which he was engaged, was the mouth of the river Glein. The second, third, fourth, and fifth, were on another river, by the Britons called Duglas, in the region Linnuis. The sixth, on the river Lussas. The seventh in the wood Celidon, which the Britons call Cacoit Celidon. The eighth was near Guinnion castle, where Arthur bore the image of the Holy Virgin, mother of God, upon his shoulders, and through the power of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the holy Mary, put the Saxons to flight, and pursued them the whole day with great slaughter. The ninth was at the city of Leogis, which is called Cair Lion. The tenth was on the banks of the river Trat Treuroit. The eleventh was on the mountain Breguoin, which we call Cat Bregion. The twelfth was a most severe contest, when Arthur penetrated to the hill of Badon. In this engagement, nine hundred and forty fell by his hand alone, no one but the Lord affording him assistance. In all these engagements the Britons were successful. For no strength can avail against the will of the Almighty.” Giles, 28-29.

[12] “But when these had departed out of this world, and a new race succeeded, who were ignorant of this troublesome time, and had only experience of the present prosperity, all the laws of truth and justice were so shaken and subverted, that not so much as a vestige or remembrance of these virtues remained among the above-named orders of men, except among a very few, who, compared with the great multitude which were daily rushing headlong down to hell, are accounted so small a number, that our reverend [venerable] mother, the church, scarcely beholds them, her only true children, reposing in her bosom.” Giles, 23.

[13] “But our Lord’s own flock and its shepherds, who ought to have been an example to the people, slumbered away their time in drunkenness, as if they had been dipped in wine.” Giles, 18.