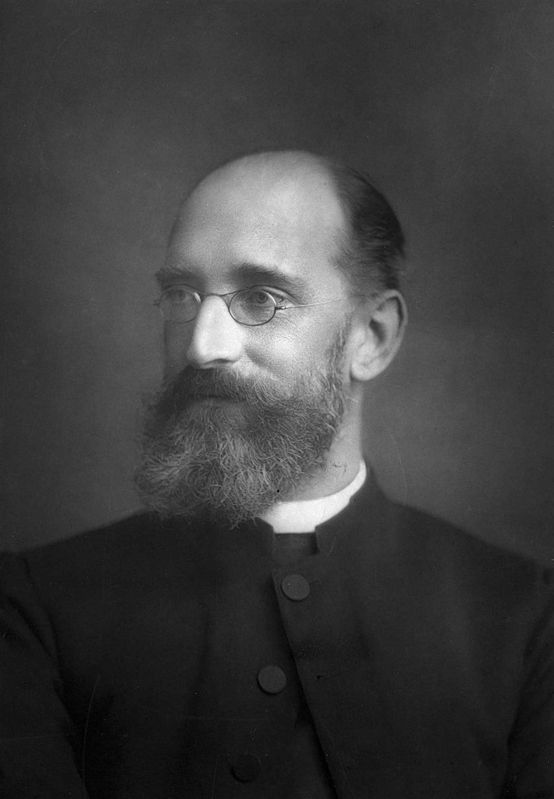

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Historical Essays and Reviews, by Mandell Creighton (published 1911).

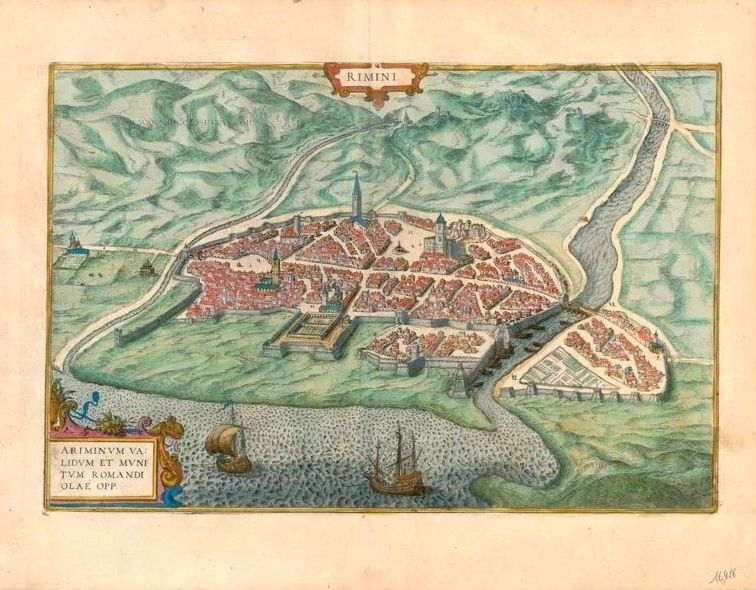

Rimini is a spacious town, with many large piazzas. It lies pleasantly on the bank of the river Marecchia, whose mouth once formed a fine harbour, but the sea has receded and has left its traces on the marshy tract which now separates the town from the coast. The country immediately round Rimini is a plain lying between the sea and the spurs of the Umbrian Appenines, which form a fine background to the fertile fields. Most striking among these hills is the rugged outline of Monte Titano, which shelters the towers of San Marino.

Apart from its pleasant surroundings, Rimini is a town full of varied interest. Its position at the mouth of a river marked it out in the earliest times as an important place. It was an old Umbrian settlement; and under the Romans was a stronghold on the frontier of Italy proper, at the junction of the two great Roman roads—the Via Flaminia and the Via Emilia—which formed the chief lines of communication between Rome and the north. The student of Roman antiquity will find in Rimini two splendid memorials of the early Empire. Augustus began, and Tiberius finished, a massive bridge over the Marecchia at the point of junction of the two great roads. The bridge has withstood even the treacherous changes of the sandy river, whose deposits have driven back the sea a thousand yards since the bridge was built. It is true that the pillars have slowly sunk, the bridge has lost its original roundness, and the grace of its proportions has suffered. But the main structure has survived, and only one of its fine arches shows traces of repair. The key-stones of the arches, adorned with vases carved in relief, the niches of which relieve the wall spaces between the arches, the massive cornice with its rich sweep of moulding—all these denote the thoroughness and carefulness of Roman workmanship. Equally important is the triumphal arch of Augustus, which spans the road leading from the town to the bridge. It is built of Istrian limestone, and has on each side of the arch a Corinthian column which once held a statue on the top. Between the two columns and the arch are medallion reliefs, which still remain—heads of Jupiter, Minerva, Mars and Venus. The architrave has been somewhat spoiled by additions of mediæval brickwork, which were requisite to convert the arch into a fortified gateway in the city wall. Still, the proportions of the arch and its fine sculptured work had a powerful attraction for the great architect who in after days drew from it his inspiration for the great artistic monument of the city.

I need not trace the fortunes of Rimini in the troubled times that followed on the fall of the Roman Empire. Nominally it passed into the territory which was subject to the Holy See. Really, it followed the example of other Italian cities, and passed under the domination of a noble family, the Malatesta, who from their castle of Verucchio, on a rock a few miles down the Marecchia, developed such a habit of interfering in the affairs of Rimini that their permanent protection was found necessary by the citizens. Early in their history the Malatesta lords of Rimini appear in a lurid light, and the verses of Dante have rendered immortal the story of the unhappy love of Francesca da Polenta, wife of Giovanni Malatesta, for her husband’s brother Paolo, surnamed Il Bello.

I pass on, however, to the most famous of his line, Gismondo Malatesta, who ruled over Rimini from 1432 to 1468, and made his city one of the great centres of Italian art.

If we read only the records of the history of the time, we should reckon Gismondo Malatesta as a brutal ruffian, little removed from a bandit, who was the scourge of Italy, and whose violence was restrained by no considerations either of principle or expediency. He was excommunicated by Pope Pius II as a heretic who denied the immortality of the soul, and had committed every crime, mentionable and unmentionable alike. His life, the Pope says in a summary, was defiled by every villainous and disgraceful deed. Nay, the Pope burned him in effigy in Rome; and it is worth noting that he employed the best sculptor in the city to make the effigy, and paid handsomely to have a good one. “The effigy,” says Pius II with complacency, “had the face, the figure, the dress of Gismondo, so that you would have said it was the man himself rather than his semblance.” Out of the mouth of the figure issued a legend, “I am Gismondo Malatesta, king of traitors, enemy of God and men.” This is a terrible character; but it must be remembered that papal censures are never wanting in comprehensiveness. Pius II had no cause to love Gismondo Malatesta; but though he fulminated against him as Pope, he still had something to say for him in private. “Gismondo Malatesta,” he writes, “had great powers of mind and body, and was richly endowed with eloquence and military skill. He knew history, had no small acquaintance with philosophy, and, whatever subject he pursued, seemed born for it especially.”

Strange as it may seem, these two judgments of Pius II were both true, and Gismondo Malatesta is the most conspicuous example of the wondrous contradictions of character in which the Renaissance period was so fertile. Gismondo thoroughly mastered the lesson that to man all things are possible. He trusted to himself, and to himself only. He pursued his desires, whatever they might be. His appetites, his ambition, his love of culture, swayed his mind in turns, and each was allowed full scope. He was at once a ferocious scoundrel, a clear-headed general, an adventurous politician, a careful administrator, a man of letters and of refined taste. No one could be more entirely emancipated, more free from prejudice, than he. He was a typical Italian of the Renaissance, combining the brutality of the Middle Ages, the political capacity which Italy early developed, and the emancipation brought by the new learning.

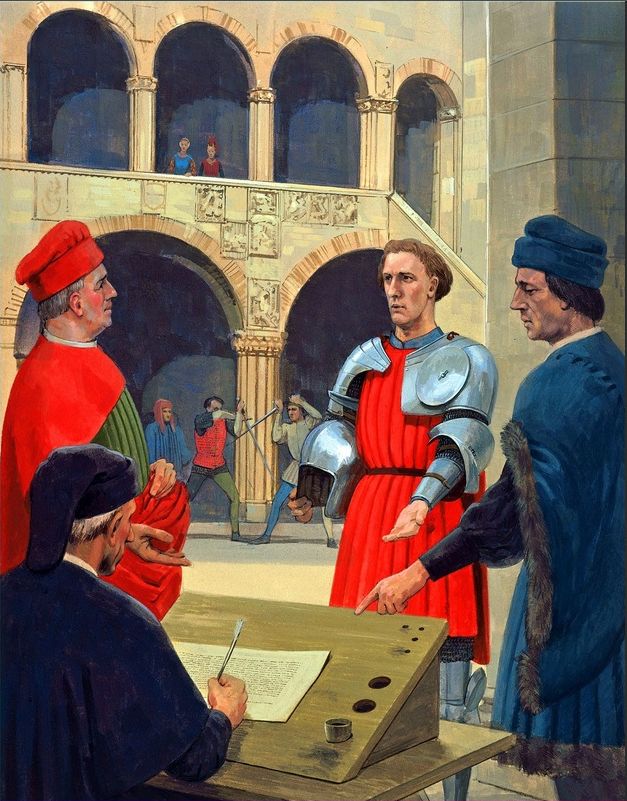

Italy alone could supply the position which rendered such a man possible. Nominally a vassal of the Holy See, he knew that he must maintain himself by his own capacity against the growing power of the Pope and the hostility of powerful neighbors. To fortify and embellish his capital were measures of political wisdom as well as of private preference. Moreover, it was necessary for him to hold a larger position in Italian affairs, and to enjoy larger revenues than the lordship of Rimini could give. For this purpose he, like other petty rulers, adopted the profession of a soldier. On the decay of the old citizen militia there grew up in Italy bands of mercenary troops, whose services were hired to those States which wished to go to war. At first these troops were led by foreign adventurers; in time the Italians organised bands of their own. The leaders of these condottieri rapidly rose to importance; and the princely house of Sforza, at Milan, sprang from a peasant of the Romagna, who embraced the profession of arms. Soon, however, these wandering generals were superseded by the smaller rulers of cities, who undertook the task of keeping under their command bodies of troops, whom they were willing to let out to hire to those of their neighbors whose pockets could afford the expensive luxury of war. It was not altogether a bad bargain for commercial states. The Florentines and Venetians could employ their time more profitably in trade than in military training, and when they wanted soldiers they hired them from the lords of such cities as Rimini or Urbino, who had time at their disposal for soldiers’ work. Yet this mode of warfare had its disadvantages. The condottieri fought as a means of earning their livelihood, and were inspired by no patriotic motives. In war after war the same forces came together—sometimes allied, sometimes as enemies. Each general knew the ways of the rest, and conventions were established for the purpose of conducting battles as cheaply as possible. Blows, however, were not much in favour; campaigns were carried on with much strategy, but engagements were rare. When a fight took place there was little loss of life; those who fell were mostly overthrown by the crush of their comrades. Defeat involved the vanquished in imprisonment until their ransom was paid.

Thus warfare was a very gentlemanly proceeding, and everything depended on the good faith of the general towards his employers. Before he took the field he bargained for terms, and a formal contract was drawn up and signed. Then he led the stipulated number of troops to the city which employed them, and which generally supplied a few soldiers of its own. Their temporary army was reviewed before the citizens, and one of the magistrates made a stirring harangue to the troops, and gave the commander the city standard. All this was gratifying to the Italian love of pomp, and troops were generally estimated by the cleanliness of their armour and the splendour of their trappings. When the ceremonial was over the general led his soldiers to the field; and they entered on their campaign with light hearts, for they knew they would be well paid, and that no great mischief would befall them. The Italian genius turned even warfare into a fine art.

Chief among the condottieri of his day was Gismondo Malatesta, and his ancestors had been so before him. Gismondo himself showed his courage very early. At the age of 13 he delivered Rimini by leading the soldiers to make a night attack upon the beleaguering forces. At the age of 15, immediately after his accession to the lordship of Rimini, he fought and won a decisive battle, which freed his dominions from the army which the Pope had sent against them.

This precocity is characteristic of Gismondo’s nature. He early learned to depend solely and wholly on himself. Growing up in watchfulness and in suspicion, he knew the value of energy and deceit. Tall, slender, with an aquiline nose and keen bright eyes, his face was full of penetration and quickness. His bearing commanded respect and true obedience. His soldiers trusted him, for he shared all their toils, and was the first in every danger. He was a steady disciplinarian, but he was strictly just, and he had a ready eloquence which moved men’s hearts. His courage was quite heroic; he shrank from no danger, and succumbed to no fatigue. He went hungry or sleepless without a murmur, and asked no one to do what he was not willing to be the first to do himself. Passionate in the satisfaction of his personal desires, he could direct a siege with the utmost patience, and in the middle of his military operations could dictate letters to Piero della Francesca about paintings, or to Lorenzo de Medici concerning the decoration of a chapel.

His artistic interests, moreover, curiously affected his political conduct. Once he had hired his troops to Alfonso of Naples against Florence. The Florentines sent their learned chancellor Geanozzo Manetti as an ambassador to Gismondo; and Manetti so fascinated him by his talk and by a present of translations of newly discovered Greek manuscripts, that Gismondo agreed to remain neutral. One is sorry, however, to find that his self-denial did not go so far as to lead him to return to Alfonso the installment of pay which he had already received. Another time, when fighting for Venice in the Morea, he went to visit the famous Platonist, Gemistus Plethon. Finding him recently buried, he disinterred his remains from ground polluted by the Turk, and carried them reverently to Rimini.

Equally remarkable are the contrasts in his private life. At times he acted like a savage brute, at others he was a model of courtesy. He is said, for instance, to have seated one of his servants on the fire, and held the poor wretch there until he perished. A terrible story was current of his wild and savage passion for a German lady who passed through Rimini with her husband, and how he lay in ambush to seize her on her departure. Her escort was stronger than he expected, and fought desperately, till at last Gismondo, unable to endure the thought that his prey might escape, rushed madly at the lady and foully slew her. Yet this same man felt a profound and intellectual love for a lady of Rimini, Isotta degli Atti, to whom he wrote poems, and whom he celebrated in every way that art made possible. It is true that he married two wives from political motives, but Isotta was the lady of his heart, and in the end he married her as his third wife. The following sonnet shows plainly enough the sincerity of Gismondo’s passion, and is a fair specimen of his poetic power: it is addressed “To Isotta” :—

O delicate sweet light, soul lifted high,

O gentle creature, from whose worthy face

Beams the clear lustre of an angel’s grace,

In your sole excellence my hope doth lie:

My safety’s anchor, rooted fixedly,

You moor my feeble bark in one safe place;

My being’s prop and stay in every case:

Pure turtle dove of sweet simplicity.

The grass, the flowers, bend low before your tread,

Rejoiced to be of such sweet foot the prize,

Stirred gently by your azure mantle’s sweep;

The sun, when in the morn he lifts his head,

Rises vainglorious, but when you he spies

Discomfited he hastes away to weep.

The many representations of Isotta which have come down to us do not suggest any physical charms which could account for Gismondo’s profound and lasting attachment to her. She looks tall, gaunt, bony, large-featured, with a prominent nose and a long ungraceful neck. Her strong character, rather than her personal beauty, must have made her attractive to Gismondo. At all events, he paid her homage such as rarely falls to a lady’s share. Medallists, sculptors and painters reproduced her face; poets were bidden to sing her praises; the monogram S[1] of Sigismundus and Isotta adorns the works which commemorate Gismondo’s name, and the inscriptions Isotta Italæ Decus, Divæ Isottæ Sacrum still testify to the wish that her name should be immortalised.

This sketch of the character of Gismondo Malatesta is necessary for the understanding of the great monument which he raised in Rimini, every detail of which bears the impress of the personality of its founder. In token of his gratitude for his success in war, Gismondo vowed in 1445 to build a church in Rimini, and he carried out his design in a way which made his church unique among the ecclesiastical buildings of Italy. Even in his own day Gismondo’s church was an amazing thing, and Pope Pius II said, “He built in Rimini a noble church in honor of St. Francis, but he so filled it with pagan works that it seemed not so much a Christian church as a temple of unbelievers who adored false gods”. Posterity has endorsed the Pope’s opinion, and to this day the church is little known by the name of its patron saint, but is called in Rimini the Tempio Malatestiano (the Temple of the Malatesta). Gismondo chose as the object of his vow the existing church of St. Francis, the burial place of his family, and he summoned as his architect the great Florentine, Leo Battista Alberti.

Few men, even amongst Italians, possessed greater natural gifts, and cultivated them with greater care, than did Alberti. His many-sidedness, his versatility, his vast knowledge, and his fine perception are equally marvellous. Supreme in martial exercises and athletic sports, he was eminent as a musician, as a scholar, an architect, a painter and a poet. He was also a student of the exact sciences, physics, mechanics, astronomy, medicine and law. In Florence he has left us proofs of his architectural skill in the façade of S. Maria Novella, and in the severe and stately lines of the Rucellai Palace. If Brunelleschi was the founder of Renaissance architecture, Alberti gave life to the classical forms of construction, and nowhere more conspicuously than in his work at Rimini.

Gismondo’s first intention was to rebuild the church of St. Francis, but out of respect for the tombs and chapels which it contained he changed his plan, and commissioned Alberti to enclose the brick building of the thirteenth century in a case of marble, so as to preserve the old chapels. This difficult task Alberti accomplished, his genius only found greater scope in grappling triumphantly with the limitations imposed upon it. For the façade Alberti took his inspiration from the noble proportions of the Arch of Augustus. It was a happy thought to weave together the past and present glories of the city, and mark significantly the nature of the architectural revival which he had undertaken. Three stately arches, separated by Corinthian pillars, form the façade; in the middle of the central arch is a simple doorway giving access to the cathedral. Massive simplicity and grace of proportion give this arrangement an exquisite charm. The sole ornamentation is on the strip of red Verona marble which crowns the basement and supports the bases of the columns. As this was exposed to rough usage, the ornaments are simple and not cut in relief, but the monogram of Sigismund and Isotta alternates with the rose and elephant, the badges of the Malatesta, and here and there are medallions with inscriptions and coats-of-arms. Only in the spaces above the arches hang six crowns of flowers and fruit, like votive garlands, and on either side of the door are carved long-flowing wreaths to represent the offerings of the faithful. A massive entablature surmounts this first storey of the façade, and above it rises two pilasters which enclose a bay. Unfortunately, the work was never finished, and the gable of the old Gothic church peeps out incongruously between the pilasters. The imagination has to supply the rest of Alberti’s design. The side walls are treated with equal simplicity and grace. A series of arches, of the same size as the side arches of the façade, form an arcade along the walls; but they are real arches, leaving visible the walls of the old church, and in the recesses which they form are placed antique sarcophagi containing the bones of men of letters whom Gismondo delighted to honor. It should rather be said that they were meant to contain their bones, for most of them are cenotaphs. Here, however, rest the remains of Gemistus Plethon, which Gismondo brought from the Morea, and each of the tombs in inscribed with the glories of him for whom it was intended.

If the outside of the church is imposing through its simplicity, the interior is overwhelming by the richness of its ornamentation. Yet even here the severity of the early Renaissance is at once apparent. The main lines of the architecture are respected, and the decoration is but an embroidery, not an addition to the structure. The interior shows a nave of large expanse, with four chapels on each side, separated from one another by a space of wall, flanked by pillars which support Gothic arches extending to the roof. One chapel on each side has been walled in, to make it a more secure receptacle for precious relics; the other six are separated from the nave by balustrades of marble and porphyry. Each chapel is lighted by two Gothic windows, between which stands the altar. The walls and chapels of the interior are those of the old building, and Alberti’s skill is conspicuous in the harmonious blending of the two styles. On classical columns rises a Gothic arch at the entrance of each chapel, but the pilasters which are carried up between the arches reconcile the eye to the transition between the two styles which is everywhere apparent.

Wherever the eye falls it meets with decoration, rich through its profusion, yet severely simple in its details. All is of the same period; all is dominated by the same thought, and inspired by the same taste. Everything is full of symbol and allegory, yet the symbolism is not Christian, but speaks of Gismondo and Isotta, and the glories of the Malatesta line. Monograms, scutcheons, crests recur in new combinations on the balustrades, the friezes, the pavement, the roof, everywhere. Roses, elephants, and the interlaced initials of Isotta and her lover meet the eye in the most unexpected places. Elephants of black marble form caryatids or pillars or support tombs against the wall.

Everything speaks of the lord of Rimini, everything is inspired by the simple elegance of the classic style. The spirit of old Roman art has been set to express the passionate aspirations of mediæval Italy, and the splendid result has been employed as the decoration of a Christian church. Nowhere has the Italian Renaissance expressed itself so frankly, so joyously, as in the temple of the Malatesta at Rimini.

Every detail of this decoration merits attentive study. On the side walls of the chapels are carved in slight relief lovely forms of choiring angels; on the balustrades stand Cupids bearing scutcheons; the columns are adorned with plaques of marble reliefs, where, from a blue background, allegorical figures detach their simple outlines. The work is conceived in the Tuscan manner, which Donatello perfected, but it has an abandonment and joyousness of its own. We ask ourselves what does it mean, and when did it come? The best answer to these questions has so far been given by M. Yriarte in his important work on Rimini.[2]

Many of the reliefs explain themselves, and are but purely decorative. The most beautiful among them is a series representing cherubs playing upon instruments of music. Draped musicians play the guitar, beat the tambourine, dance with cymbals, and blow trumpets; while others sport with the emblems of Isotta and the badge of Gismondo. The whole workmanship recalls the sculpture of Luca della Robbia and Donatello for the music gallery of the cathedral of Florence, and the sculptors at Rimini were clearly under the influence of these great masters. Even more curious is the series of reliefs representing the planets. Diana, holding a crescent, is mounted on a triumphal car drawn by two horses; Mars, as a warrior, with drawn sword and brandished shield, stands on a chariot armed with scythes; Venus rises from the waves, drawn by swans who walk upon the waters, while a flock of doves hover over her head. Another series which sets forth the signs of the zodiac is less interesting, as its representations are more realistic, and suggest a collection of strange animals. Thus, a goat browses on a hill-side; a huge crab is suspended in the heavens, while underneath is a representation of the sea with Rimini on its shore. Sibyls and Old Testament heroes also occur, but these are more ordinary subjects. Suddenly, however, we come upon a chapel which is adorned with designs of the games of childhood. Little amorini, full of the mischievous joy of infancy, sport amidst the waters, chase ducks, ride on shells, or are mounted on the backs of dolphins; or they dance merrily round a fountain, conduct their leader in a mimic triumph, and even ride cock-a-horse, and play at horses. The next chapel rises suddenly to most serious allegory, and represents the works of man. It is the later counterpart of Giotto’s large conceptions round the base of his campanile, or the more sombre allegories that run inside the doorway of St. Mark’s at Venice. Symbolism has become more complicated, more learned, more pedantic. Giotto frankly represented man at his labour, whatever it might be. Here, on the other hand, we have impersonations. Agriculture is a woman gazing on the face of the sky, and holding fruits in one hand, while with the other she scatters seed upon the earth; Education is a stately dame with a staff thrown over her stalwart shoulder, and looking down upon a group of boys and girls who run to clasp the hem of her garment; Music is a maiden with rapt face and timid awe-stricken mien, who opens her lips in song, and holds in her hands a guitar.

For the student of Italian art all this work is full of the deepest significance. It gives a new sense of the richness and fertility of the age in which it was done. The records relating to it have all perished; and critics once wished to assign the sculptures to the great Italian masters, Luca della Robbia, Donatello, and the like. M. Yriarte has gone far to prove conclusively that they were the work of much smaller men—Simone Ferucci, Agostino di Duccio, Bernardo Cuiffagni. But all owed something to the presence of Alberti; and their work was directed by Gismondo himself, and supervised by his chief minister art, Matteo da Pasti, whose fame survives as a medallist. All Italy was full of artists. A fitting opportunity alone was needed for congenial work, and the work was sure to be exquisitely wrought. The fiery nature of Gismondo found ready instruments to accomplish what he wished; his desires were so exactly in accordance with the artistic spirit of his time that they were executed with precision and with force. The temple of the Malatesta remains what Gismondo meant it to be, a memorial of himself, of his life, his character, his ideas, and his love. The only thing inside the church that rises to another level is a fresco by Piero della Francesca, representing Gismondo kneeling before his patron saint, St. Sigismund. It is painted above the door of the Chapel of the Relics, and in its simplicity and strength leads back our minds from the multitudinous details of the decorative work to the grand façade of Alberti.

The church was not finished outside, and the decoration of the choir was never begun, for things at last went very badly for Gismondo. His unscrupulousness made him a vast body of enemies, and Pope Pius II in the end was much too strong for him. He was defeated by overwhelming superiority of numbers, and was deprived of most of his dominions. His unquiet spirit found some occupation after his downfall in fighting against the Turks in Greece, where he died at the age of fifty-one. With him the glory of Rimini departed.

______________________________

[1] Rendered in the original text as:

[2] Francesca di Rimini, In Legend and History, by Charles Yriarte (1882)