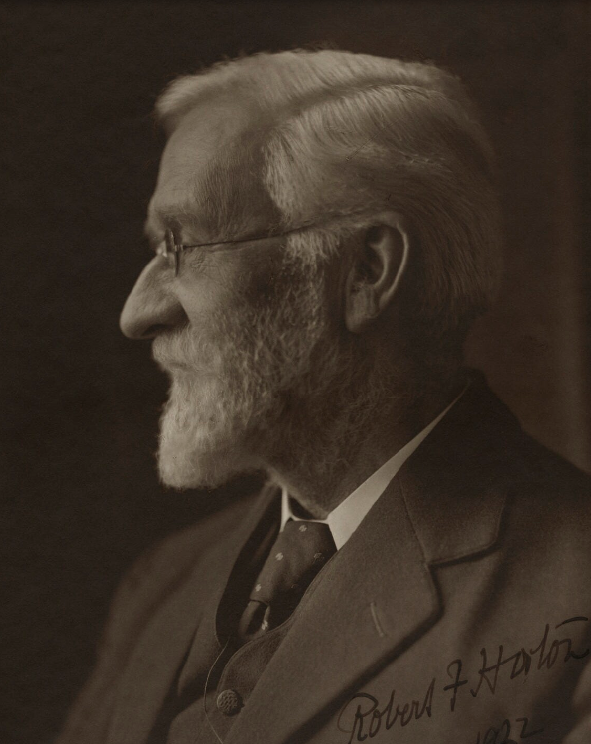

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from The Conquered World, and Other Papers, by R. F. Horton (published 1898).

“Be of good cheer; I have overcome the world.” — JOHN xvi.33.

It is the parting message which the Lord gave to His disciples as a body. After that He turned to pray to the Father for them, and then spoke no more with them. The words were therefore designed, no doubt, to ring out as the key note of the Christian’s life and of the Church’s history until He comes. Set this side by side with the parting message of Buddha. He, as he was dying, said to his disciples, “Work out your salvation with diligence.” This is a noble, a necessary, we might even say, a Christian precept. But it presents a remarkable contrast, as the farewell utterance of a religious leader, with the words of Jesus which are now in our ears. The one message suggests travail and effort; the other suggests victory. The words of Buddha throw men on their own resources; the words of Christ throw them on the strength of Another. This message breathes despondency; that breathes hope. The contrast will almost explain why it is that wherever Buddha is saviour pessimism, and wherever Christ is Saviour optimism, prevails.

Yet there are some Christians whose general tone and practice seem to imply that they are more familiar with Buddha’s last words than with Christ’s. “Work out your own salvation with diligence” has been the keynote of many strenuous, well-meant Christian lives. But when Christianity has been triumphant and progressive it has been so in virtue of these thrilling words of its Leader. It has failed, and it does fail, whenever Christian men forget them, or lose their meaning, or do not appropriate them in such a way as to connect themselves with the force of which they speak.

It was a remark of Mr. Ruskin’s that the Christian Pulpit fails in its effect because it speaks so much of what men must do to earn salvation, and so little of what God has done to give it. To dwell too strenuously on the things we have to do fosters the Buddhist tendency in us all, and harmonises only too well with the claim to personal merit which we are always disposed to make. On the other hand, it requires much grace and humility to be always insisting on the transcendent facts of the Christian Redemption, which exclude boasting, and place all, even the best of us, in the lowly attitude of recipients.

Now let us try to see what the Lord meant by this last message of His; and if the meaning should dawn upon our minds while we are considering it, we may encourage one another to accept the truth, and then to live in the spirit of this creed. It may, perhaps, surprise us to find that we have attached very little definite meaning to the words. Like many other of His thoughts which have become the commonplaces of Christianity, this is not much observed. For we do not stop to geologise on the flagstones of the pavement, and the familiar truths of the Gospel often pass almost as unnoticed and unexplored. It is quite conceivable that many truly Christian people have never faced the full force of the words. Let me repeat them, marking by an emphasis the implied contrast: “These things I have spoken to you, that in Me ye may have peace; in the world you have tribulation, but be of good courage, I have overcome the world.”

This is the language of a conqueror. Two forces had been engaged, the world and Jesus. Jesus had gained the victory. We, presumably all of us, are either in the world or in Jesus. If we are in the world we stand on defeated ground, and are exposed to all the penalties of defeat. If we are in Jesus we stand upon the Conqueror’s ground, and share the fruits of His victory; we have the peace which His prowess has won.

We will concentrate our thought for a moment on the words: “I have conquered the world.” It is possible, and easy, to give them two meanings, one of which would make the statement untrue, the other of which would deprive it of practical power. We might take them to mean either “I have already subdued the whole world to Myself, and won all mankind to My allegiance” — this would be untrue — or, “I have obtained a personal victory over the worldly powers” — this would be ineffectual.

The first of these meanings is quite out of the question, for “we see not yet all things subjected to Him.” To many it seems quite the contrary. There is a general impression — even among Christian men — that the victory of Christ is, to say the least of it, very imperfect. Many in their hearts think that the conflict between Christ and the world ended really in favour of the world. It slew Him. It has perverted His teaching. It has travestied His thought. It has resisted His Church, and when resistance has seemed giving way, it has subtly stolen within the entrenchments, and as a traitor has betrayed the position to the foe. There are Christians who are too sad to say much about it; they try not to think of it; but it is their shuddering conviction that the world has proved too much for their Lord. They see Him in their imagination, as Clough saw Him, a pale, discomfited Ghost that sits upon that far-off tomb “by the lorn Syrian town.” This we may hold to be exaggerated, and deficient in spiritual insight; but that it is possible for honest men to take such a view shows that we cannot understand the words in the way proposed, for that would make them an idle boast.

But the second meaning is open to objections almost as serious. Suppose He only meant that He had obtained a personal victory over the world by resisting its temptations, and turning aside from its attractions in the way which is described in the Gospels. That He did obtain such a victory, few will be prepared to deny. But so, in a certain sense, did Buddha. There are even points in the renunciation made by the Hindu prince, and in the story of his self sacrificing life, which make one wonder whether in that personal sense he did not as truly vanquish the world as Christ did. Indeed, there have been many examples of such a victory. And it is not necessary to underrate the influence which these examples exercise over us all. To know that there has been even One who has been proof against the world, unseduced by its allurements, undazzled by its splendours, unaffrighted by its terrors, is a strength and a joy to all earnest souls that pay attention to the fact. And merely from this point of view the unworldly life of Jesus, passed in the world, affords a rallying-point for noble effort, and exercises a constant power over the thoughts of men. But how inadequate would this be to account for the inspiriting words, “Be of good cheer.” Nay, if we are to suppose that this is all He meant by overcoming the world, the exhortation is not wholly free from a tone of mockery. “In the world you have tribulation, you are exposed to its perpetual trials, and borne down by its terrific onsets; but, courage, I have escaped it, I have been superior to it. You are defeated in the fray; but see, I sit on the hill above the tumult beyond the reach of harm.” It is a thought of despair. What can it profit you, when you are carried away by the vain ambitions of the world, tormented by its inworking lusts, or overwhelmed by its accumulated sorrows, to be told that He, the strong One, overcame; that He scorned the repute of men, the wealth, the comfort which might have been within His reach, that He showed no weak point to the assaults of sensual passion, that in acute pain or heartbreaking sorrow He could say, “I have overcome”?

I have dwelt upon these two obvious meanings — I might almost say natural meanings — of the words, because, perhaps, some of us are tempted to abide in them, and so to miss the real meaning. If, therefore, you have been in the habit of attaching one or other of these interpretations to the last message of Christ, will you admit the force of what has just been said, and recognise that you have not yet arrived at what is really meant?

Brood upon the words, let them tell their own tale, and you will presently see that they could mean nothing less than this: The World, in the familiar sense of the term, which it would be a needless diversion to define, was too much for man; it mastered him and held him in bondage. Like a strong man armed it kept the house in which we were obliged to live, with a kind of brute right over us. Just as before 1862 the negroes of the United States were born into slavery, so men were born into the house of bondage, sold under sin. It is difficult to conceive what this malignant Power was in its pristine force, for we only see it now in a manner vanquished. Yet, broken and unmasked, how strong it still is, and what an incredible fascination it exercises over us as men! But Jesus engaged in a hand to hand conflict with this Power. His earthly life from beginning to end was a tussle of this kind. In the main it was waged in the Invisible; but from time to time signs appeared, and those who were about Him saw the agitation on His face and were amazed, saw the sweat as great drops of blood, heard the agonised cry as of a soul forsaken by God. But that conflict, difficult for us to conceive, because the Power against which He strove is to us intangible and almost inconceivable, ended in His victory. He entered the house of the strong man armed, and spoiled him; He took captivity captive; he broke the sceptre, and overturned the throne. Just as the proclamation of slave-emancipation in America made every slave free who chose to claim his freedom, so the victory of Jesus secured a complete victory for all men who would enter into it. He could say, at the last, with a clear confidence, that the fight was finished, “I have conquered the world,” and then He ascended up on high, leading captivity captive, to receive gifts for men.

Henceforth no man need be enslaved to the world. Freedom was purchased for all. And when He gathered His chosen disciples about Him to send them out as messengers He did not tell them to proclaim “work out your salvation with diligence; wrestle, fight, and overcome.” But He charged them to proclaim the glad and significant tidings, that He had overcome, victory was secured, and whoever would believe might enter into the fruits of it, and into that peace which is the desired result of victory.

Here we are touching on words which are very familiar , too familiar almost to retain our attention. But this is the very point where men frequently miss the whole bearing of the situation. They see and admit in a vague way that Christ obtained such a victory as has been described, but they make no further use of the fact. They do not see how to appropriate it. And, consequently, with this great fact before them, and with His thought of love ever pressing upon them, they turn aside to wage their own warfare, to strive for their own victory. Instead of standing on victorious ground and sharing a victory that is gained, they continue to think that they have to gain the victory themselves, and enter on a course of Christian life which is — how can it be otherwise? — an unbroken series of defeats.

We have not to gain a victory, but to enter on a victory gained.

Let me attempt an illustration. I remember reading an account, I think it was, of the Eiffel Tower in a thunderstorm. There was an aerial chamber in which one might sit , with the lightnings a-play on every side. Indeed, the lofty summit attracted the electric currents, and drew them to the ground. But the chamber was so constructed that one within it remained unscathed. In the centre of commotion, circled by the electric blaze, there where all the storm was raging, he was safer than in the most sheltered retreat. Christ’s victory means that here, right in the midst of this tumultuous and perilous world, He has secured an impenetrable refuge, the enchanted chamber of victory. It is entered by faith, and there one may smile at the impotent rage of the world. Unscathed, unalarmed, in Him and Him alone we may be secure.

But if this image conveys a true idea, it must evidently make all the difference conceivable, whether we take our stand in the charmed chamber of victory or outside it. A Christian who is just outside it may be exposed to greater peril than a person who is far away from it. He is in the centre of the conflict; but he has no victory except his own to rely on, and that victory is very uncertain.

Now, can we help one another to a practical conclusion? For the great difference between Christians is not one of creed or church, but rather this practical difference, that some Christians have found the way of sharing Christ’s victory, while others are seeking to gain a victory of their own, almost as if His victory had been a mere chimera.

Place side by side the Master’s utterance, and that of His beloved disciple: “Be of good cheer, I have overcome the world,” said the Master. “This is the victory that overcometh the world, even your faith,” said the disciple.

Christ’s is a victory achieved once for all; ours is merely the appropriation of His by faith. Put it in this way. When you genuinely believe in Christ, and look at things from the standpoint of His cross, you see the world as a vanquished power, the fetters of sin broken, the glamour of its lusts dissipated. You see the principalities and powers led in captivity as Jesus “makes a show of them openly.” Within the circle of His victory the world’s promises seem idle, its pleasures pains, its successes perils, just as, within the circle of the world, the spiritual things appear unreal, and the voice of Jesus sounds faint and distant. It is by faith that you step within the circle of His victory and occupy that point of outlook for life and time. By faith you take your place within the lines of His accomplished work, so that the spell of the world is broken, its pomp exposed as a vain show, its unreality demonstrated to perception .

The words seem cold and inadequate to convey the thought to one who is not disposed to make the personal experiment. But let us push into detail, to give such concrete and tangible reality to the subject as it admits of in speech.

Christ has vanquished sin. But you are assailed by some too familiar sin. It has overcome you before, and it threatens to do so again. Like swelling tides, it rises to submerge the soul, and you do not see how you can take arms against it. It has effected some entrance within. You strive, but it seems in vain. You pray, but prayer seems useless. Now take that step of faith, which sets you in the circle of Christ’s victory. Recognise that He has overcome; that this very sin is what He has overcome; that it is a monster whose power is broken. Now what happens? The effect is miraculous. Those swelling floods subside. From the face of witchery the mask is torn, and the hideous lineaments appear. Passion dies. The soul is borne up on a strength not its own. The invisible stream of power — Christ’s victory — sets easily against the combined forces of sin. No words can explain the sweetness and joy of that experience.

But the world is with us not only as an allurement to personal sin. It often presents its most depressing front to us as a combination of evils with which we have no power to cope. Often, as just now, the grim monsters of reaction, of corruption, of materialism, of sensuality, of superstition and its companion doubt, surge up against the feeble defences of the Church, bearing down the unarmed protectors of her walls.

Who can take arms against this sea of evils? Now, it is precisely in this broader issue of the world’s sin and ruin, that, if we would be but advised, we should more eagerly still take refuge by faith in the achieved victory of our Lord. Not only can this alone bring us assurance and peace; this alone can still the angry tumult and bring calm after storm.

When I was crossing the Atlantic in the Umbria, I was told how on the previous voyage the main shaft of the propellor had snapped, and the great ship lay helpless at the mercy of the seas. A gale was blowing, and with such force that soon there was serious apprehension, as the vast waves broke over the upper decks with terrific force, and there was no steering “way” to put the prow to the seas. And then when the uneasiness was at its height, the captain had some barrels of oil poured out of the portholes.

What a trifling thing it seemed; how impossible to calm those raging waters, and to provide a safe riding for that enormous hulk by such a simple operation! But presently the waves were calmed, none broke on deck, and the ship rode easily on the waters.

This simple step by faith into the victory of Christ produces a a similar effect. It not only calms the troubled spirit and gives peace within, it actually stills the waters. That is to say, there is no other way of successfully opposing the forces of evil, of taking the Gospel to the heathen, or of bringing our own country into the enjoyment of it, but by fearlessly stepping out on the fact that Christ has overcome.

We are trying to do too much. We are not giving play to the great thing that is done. We fight bravely a losing battle, instead of standing boldly in the battle won.

There are many who are waking up to this truth, and miracles are wrought by their hands; they in their turn wake us; but as the hosts of the Lord become generally and habitually alive to it, the reality of Christ’s victory will appear in all its magnitude, and we shall march, each man straight before him, over the prostrate walls to take possession, in His name, of the conquered world.