The works of William Faulkner are infused with several important themes, including a discussion of the confrontation that the individual has with society. This confrontation takes different forms that are determined by the society in which the individual is found, whether the ante-bellum South, the post-war/reconstruction era or the early 20th Century (Volpe 21-28).

Faulkner’s fully developed characters tend to fall into one of three types: “Primitive Man”, “Old South,” or “Modern Man.” The progression through these types is a downward trip according to Faulkner. “Primitive Man” is the ideal. The “Old South” persona is one with many positive aspects, but one that is beset by negative traits, as well. “Modern Man” is truly Faulkner’s ultimate villain. “Primitive Man” is one who is controlled by passion or emotion. He is in a healthy relationship with his surroundings. The “Old South” individual is one who also loves the land and is capable of deep emotion, but is flawed with prejudicial race relations. “Modern Man” is cold and logical, incapable of emotion and without emotional relationship with other people or surroundings. Within this framework of understanding, Faulkner places his view of the land itself. Rather than being a simple setting for his novels, the land is an active participant. Though some of Faulkner’s novels present the land’s activities more than others, the concept is prevalent enough to show that Faulkner had deep emotional contact with the land and viewed it with some anthropomorphic tendencies.

Because of the types of characters that are portrayed – and Faulkner’s views about each type – it is apparent that “Primitive Man” will have the desired view of the land and relationship with it, as Faulkner sees such things. The “Old South” persona will be more detached, but still in some sort of symbiotic relationship with the land. The “Modern Man” will be totally detached from, and at odds with, the land. This in fact is the case, as Faulkner demonstrates in various ways throughout his novels.

Faulkner presents his view of the land in explicit terms in The Unvanquished. In this novel, the two characters, Uncle Buddy and Uncle Buck McCaslin, are shown to have a unique view of the land and its relationship with its inhabitants. We are told:

They believed that land did not belong to people but that people belonged to the land and that the earth would permit them to live on and out of it and use it only so long as they behaved and that if they did not behave right, it would shake them off just like a dog getting rid of fleas. (48)

This is the quintessential Faulknerian view of the land. Throughout his novels, this belief is shown to be exactly what the land does to those characters who do not “behave.” “Primitive Man” is allowed to remain on the land throughout his life, while “Modern Man” is promptly removed. Those of the “Old South” persuasion are a type of middle ground, where those who struggle to act appropriately are allowed to remain, while those who do not are removed.

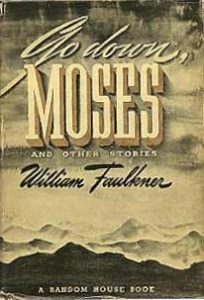

One “Primitive Man,” Sam Fathers lived to a ripe old age and died at peace with the land. After living the majority of his life as an Black man (often portrayed as “Primitive Man”), he spent his later years living away from modern society. He passed his love of the land on to Isaac McCaslin, another who was allowed to remain. Uncle Ike (Isaac) even believed that “…Sam had been training him all his life …” for this very thing (Go Down Moses 167).

It is interesting and important that most of the developed “Primitive Man” characters live to old ages. In addition to Sam Fathers and Uncle Ike, Dilsey (The Sound and the Fury), Buddy and Buck McCaslin (Go Down, Moses and other works) also live to be very old. Each of these characters were the type of people that the land allowed to remain, rather than being “shaken off.” This is an example of the implicit Faulknerian concept of “Primitive Man” being at one with nature and the land.

Uncle Ike is a good example of this type of person, who understood the proper relationship and admiration for the land. This concept is developed in Go Down, Moses in detail. We learn that he relinquished his legal claim on his hereditary property (39), understood that the land was older and more permanent than any person or family (159), and knew that though men may claim to tame the land, it was really out of their control (243-244). By taking these actions, Uncle Ike was rewarded in Faulkner’s fictional world and held in high esteem. In addition to his education from Sam Fathers, Ike is the son of Uncle Buck. Therefore, it is easy to see how he maintained this viewpoint. Buck and his twin brother Buddy have rejected some (though not all) of the racial code (a big deal for Faulkner) of the Old South by moving from their ancestral plantation home into a small shack (Volpe 393). Through their attempt to behave, they are allowed to remain. Certainly, they are not as highly regarded as Uncle Ike, but are still not rejected by the land.

All of these people who are presented in positive terms for the most part, and are allowed to remain on the land, tend to have a proper view of the land itself. They respect it. To the “Modern Man,” Uncle Ike has every right to own and possess the land. Yet, he does not believe this to be true. As he explains his reasons for moving into a small home in Jefferson, he rejects the idea that he is repudiating his possession of the land:

I can’t repudiate it. It was never mine to repudiate. It was never Father’s and Uncle Buddy’s to bequeath to repudiate because it was never Grandfather’s to bequeath them to bequeath me to repudiate because it was never old Ikkemotubbe’s to sell to Grandfather for bequeathment and repudiation. Because it was never Ikkemotubbe’s father’s father’s to bequeath Ikkemotubbe to sell to Grandfather or any man because on the instant when Ikkemotubbe discovered, realized, that he could sell it for money, on that instant it ceased ever to have been his forever, father to father to father, and the man who bought it bought nothing…[God] created the earth, made it and looked at it and said it was all right, and then He made man…He created man to be His overseer on the earth and to hold suzerainty over the earth…not to hold for himself and his descendants inviolable title forever, generation after generation…but to hold the earth mutual and intact in the communal anonymity of brotherhood, and all the fee He asked was pity and humility and sufferance and endurance and the sweat of his face for bread… (Go Down, Moses 245-246)

This very idea is juxtaposed with the view of his cousin, Cass Edmonds, who is in disbelief that Uncle Ike would relinquish control of the land. Cass believed that because Ike’s ancestors had taken the virgin land and carved an existence out of it, Ike was entitled to own and possess the land. But in Faulkner’s novels, this is an errant belief that is held by many of those whom the land shakes off.

A careful reading of Go Down, Moses shows a veritable Who’s Who of characters who thought they possessed the land, but ultimately were driven from it.

…Carothers McCaslin, knowing better…believe[d] the land was his to hold and bequeath since the strong and ruthless man has a cynical foreknowledge of his own vanity and pride and strength and a contempt for all his get: just as, knowing better, Major de Spain and his fragment of that wilderness which was bigger and older than any recorded deed: just as, knowing better, old Thomas Sutpen, from whom Major de Spain had had his fragment for money: just as Ikkemotubbe, the Chickasaw chief, from whom Thomas Sutpen had had the fragment for money or rum or whatever it was, knew in his turn that not even a fragment of it had been his to relinquish or sell not against the wilderness but against the land…(244)

These men had offended the land and had paid the price. Many were rejected. Some were allowed to remain, if they repented and/or repudiated modernism.

This “land relationship” concept can be demonstrated by looking at two locations from within Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County. First, by looking at Thomas Sutpen’s attempts to create a plantation from the wilderness in Absalom, Absalom!, one can see the final result of a cold, uncaring man and his relationship with the land around him. Secondly, in a survey of the Old Frenchman’s Place in Sanctuary, it can be seen what happens to the people who try to impose their “Modern Man” mentality upon the land.

Thomas Sutpen began life with great potential, but circumstances early in his life, and his reaction to them, caused him to become closed off emotionally. He held to the worst parts of the code of the Old South and little of the positive aspects. He refused to acknowledge the other individuals about him, except in context of what they could provide for him. He was a figure who led the way in transitioning from the “Old South” into “Modern Man.” The land did not treat him kindly.

As the novel progresses, he comes to Yoknapatawpha County and purchases the land that will be known as “Sutpen’s One Hundred” from Ikkemotubbe, the Chickasaw chief. He practically enslaves a French architect to build his plantation home. In this early stage of his story, he is not totally lost, but still has hope, exemplified by this fraternizing with his slaves (Volpe 388). However, this fraternizing quickly becomes simply amusement and he has little empathy for them.

At first, it appears that his efforts and perseverance will pay off, and he does carve a plantation out of the wilderness. It becomes a working plantation, and Sutpen finally becomes a recognized member of society, despite serious problems in that regard when he first arrived. He will eventually be elected colonel of their regiment in the Civil War, showing the respect that he had obtained. But all is not as it seems. Rosa Coldfield, Sutpen’s sister in law, states that Sutpen did not build a plantation, but “tore violently a plantation” (Absalom, Absalom! 9). The violent approach to his relationship with the land was indicative of his relationship to everyone around him. He was transforming from the primitive child he had once been, into the “Old South” mentality, where he rejects others for various reasons (including race, personal grievances, etc.), and finally into “Modern Man,” as he asks Rosa to demonstrate her ability to produce male children before he marries her, and as he compares the minor character, Milly, to a horse.

At that point, the land has had enough. He is beyond the point of redemption and has long since stopped “behaving.” The land decides it is time to shake him off. Utilizing Wash Jones, a “Primitive Man,” albeit one who had looked up to Sutpen previously, the land removes Sutpen. Over the next forty years, the land systematically removes his progeny. Eventually, even his bastard children have all died, and his house has burned to the ground. Only his descendant, Jim Bond, an idiot, remains, but quickly disappears.

Regarding the “Old Frenchman’s Place” in Sanctuary, it has become a run down house. During the time of prohibition, it is inhabited by a gang of bootleggers and murderers. However, they are not judged, in the Faulknerian sense, for these crimes, but for their mistreatment of others – their identity as “Modern Man.” The four inhabitants of the “Old Frenchman’s Place” are Lee Goodwin and Ruby, Tommy, and Popeye. Of the group, only Ruby shows herself to be concerned about others, in other words, to not be a “Modern Man.”

When Temple Drake appears in their midst, the various reactions of the three men show that they desire her, but only as an object for their own gratification. Tommy is perhaps less intrusive than the other two, but even his attitude is cold. He is eventually shot by Popeye. Lee Goodwin seems to lose all sense with regards to Temple. He basically turns his back on Ruby, who has struggled and slaved to serve him. While he doesn’t commit the crime for which he is convicted, he certainly would have, if he had had the opportunity. He is burned alive by a vigilante crowd. Popeye reacts to Temple with no apparent emotion at all. He isn’t driven by lust, but by a cold calculating realization of what he “should” do in such a situation. He is concerned about his own appearance and reputation. He gets away with both murder and rape, but is executed for another murder that he didn’t commit.

Ruby is the exception to this cycle. She follows Lee, even when she doesn’t have to do so. She prostitutes herself to provide legal counsel for him. Such an action, committed out of passion, is an acceptable thing in Faulkner’s works. She tries to protect Temple and gives her good advice. Ruby is even concerned about Horace’s reputation. By demonstrating that she is not a “Modern Man,” she is not punished in the same way. Though Lee has been killed, she is free to continue living her life. These four people demonstrate the land’s ability to “shake them off” like fleas. The three “Modern Men” are all dead. The one person who demonstrates passion and concern for others is alive and able to move on.

The two scenarios demonstrate the land’s ability to outlast, endure, and eventually overthrow anyone who does not behave. But Faulkner does not stop with an abstract concept of the land. He actually refers to it as a living thing in many passages. Go Down, Moses gives us some good observations in this regard. As Lucas begins to dig a pit to hide his still, the earth is described as “whispering…only a sigh…the whole mound had stooped roaring down at him…hurling clods and dirt at him, striking him…squarely in the face” (38).

Not only is the land described as being alive, but even as producing life. As Lucas is considered by Roth Edmonds, in comparison to their mutual ancestor Carothers McCaslin, the land comes into view. “He is both heir and prototype simultaneously of all the geography and climate and biology which sired old Carothers and all the rest of us…” (114). Here one can see the geography and climate are given equal billing with biology in producing humanity. Finally, the earth is shown to have conscious thought. In a discussion of the happenings on earth – all the bloodshed, suffering and pleasure that had soaked back into the ground, Cass Edmonds posits the thought that they would not remain. Rather, “…the earth don’t want to just keep things, hoard them; it wants to use them again” (114).

This brings the discussion full circle. Faulkner was truly concerned about man and his relationship with the land around him. But land is not a passive participant, and is often shown to be the primary instigator. Certainly, the land is often in the background, and only occasionally comes to the forefront of the discussion, as in The Unvanquished, but the interweaving of the concept throughout Faulkner’s novels shows his view on this matter. As long as people behave (primarily meaning that they strive to identified as “Primitive Man”), the land allows them to remain and struggle through their lives. However, those who are unrepentant about the “Modern” tendencies are forced off the land. Some flee to other locations, usually never to be heard from again. Others die, often at an early age, by violent means.

Because so many of Faulkner’s works are set in the same general location, it is possible to trace the inhabitants of certain locations through several generations or time frames, as we have done with Sutpen’s One Hundred and The Old Frenchman’s Place. This same evaluation could be done of other locations within Yoknapatawpha County and of other families.

Truly, the land is a living entity in Faulkner’s works. It is an active participant. It is not some impersonal force, but is living, breathing, thinking, and acting. Faulkner ties the land directly to God and his mandate to man to live within the land – not as owner and master, but as caretaker. “Primitive Man” understands this and thrives. The “Old South” persona still has strong remnants of this concept and can co-exist with the land. “Modern Man” has lost this relationship with the land and is treated like a flea on a dog. He is shaken off. This is Faulkner’s ultimate disgrace and punishment – to be rejected by the land itself.

______________________________________________

Works Cited

Faulkner, William. Absalom, Abalom! London: Vintage Random House ,1995. Print.

—. Go Down, Moses. New York: Vintage International, 1990. Print.

—. Sanctuary. New York: Vintage International, 1993. Print.

—. The Sound and the Fury. New York: Vintage International, 1990. Print.

— The Unvanquished. New York: Vintage International, 1991. Print.

Volpe, Edmond L. A Reader’s Guide to William Faulkner. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2003. Print.