Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Beyond Courage, by Clay Blair, Jr. (published 1955).

The men of the 51st Fighter-Interceptor Wing had one main objective in the war in Korea, and that was to destroy more MiG’s than the 4th Fighter-Interceptor Wing. It was as simple as that. To be sure, among these 150 pilots were grand strategists who could draw the distinction of the big and little war; there were also political theorists who could make sense — at least to themselves — out of containment, Korean style, and its relation to cold war and rice paddies. There were hard-bitten Communist haters; there were wandering idealists; there were those who had no feeling about the war, one way or another. But the glue that held together the diverse men of the 51st was that secret blend of competitive spirit and showmanship (and whatever else) that is common to all elite corps, whether made up of paratroopers, submariners, or fighter pilots.

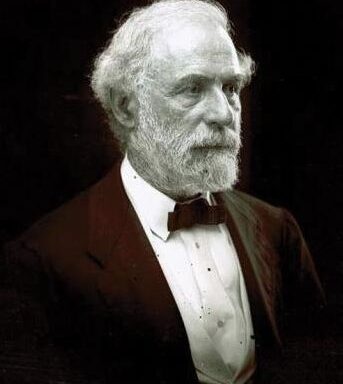

The aggressive, MiG-killing spirit of the 51st was personified in its leader, a strapping, black-haired colonel named Francis Gabreski. Gabby, as his men affectionately called him, was a terror to MiG pilots — a legend among airmen everywhere. He was an old man in terms of fighter experience. He had learned his trade early in World War II and later served under Colonel Hubert Zemke, the uncanny leader of the famous World War II 56th Air Force Fighter Group. Under Zemke, the 56th alone accounted for more than 1,000 Nazi aircraft. Gabby himself bagged 33½.

Korea was a new war and a new challenge for the old-school fighter pilots. Gabby soon found his way there and, like the others, went directly to the front lines, ready to outgun and outfly everybody, especially the men of the 4th Fighter-Interceptor. Gabby was a calculating killer. He never stopped devising new ways to shoot down MiG’s. He sometimes sat all morning at his beat-up oak desk in the “headquarters” quonset hut, just thinking. Then he would hurry down to the flight line, get into a jet, and fly up to MiG Alley to try out some new idea. Later he would spend all afternoon and evening discussing the idea with his men.

The Air Force had a term for Gabby and men like him: Tigers. The psychologists went to Korea to interview the jet aces to try to find out what a tiger had that ordinary pilots did not. They found out that tigers were usually shorter than the average American male, that they expressed themselves well, that they were friendly, soft-spoken, enthusiastic, loved competition, and were intensely alive. They usually came from large families, often broken by the death of one parent. As children, they liked hot rods and anything scientific or mechanical. They were active in sports in high school and liked to date girls. But it took more than a psychologist to find out what fundamentally made Gabby and the boys tick.

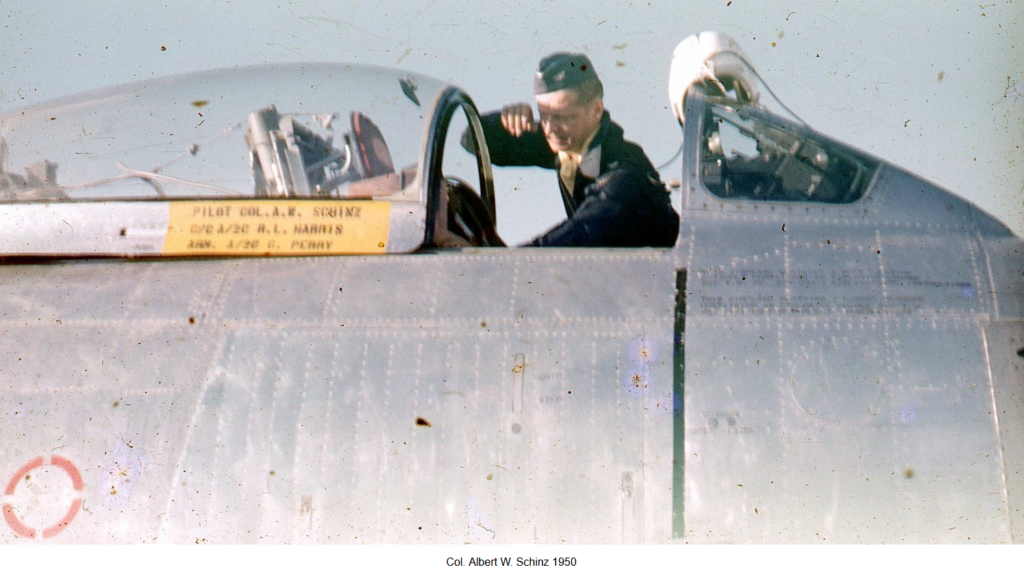

Gabby was always so busy thinking of new ways to keep ahead of the 4th Fighter-Interceptor in MiG Alley that he did not have time for minor chores. Therefore, the details of operating the base — the administrative, supply, and personnel problems — were left up to Gabby’s number-two man, a stocky, thirty-three-year-old colonel named Albert W. Schinz.

All of his adult life Schinz had been an Air Force officer. He was born in Ottawa, Illinois, and after graduating from high school, he spent two years in junior college and then, in March, 1940, joined the Air Force as a flying cadet. In January, 1942, after various stateside assignments, he went overseas with the 41st Fighter Squadron and flew 174 combat missions in the South Pacific.

After World War II, the Air Force sent him through college, and he obtained a degree in business administration. Later, in the years before the Korean war, he served routine tours of duty in the Air Force, largely of an administrative nature. In the second year of the war he was assigned to the 51st, straight from the Pentagon. Now he was trying to regain his tiger status but found it difficult, because he had to devote most of his time to administering the base and could only occasionally run up to MiG Alley for a fight.

Schinz was a restless tiger though only a part-time one. He could never sit still. He especially did not enjoy sitting at a desk. He liked to get out of the office and walk around the base, and down to the flight line, to find out what “the boys” needed or might soon be needing. Often he jumped into his jet and flew to air bases in Japan to beg, borrow, or steal new equipment for his pilots, or to push personally one of his proposals through higher headquarters. Such energy and intensity led him to plan and build a handsome noncommissioned officers’ club. When that was finished, he ordered plans drawn up for an officers’ club. Always full of new ideas, projects, and unwavering opinions, Al Schinz was a fountain of talk and action.

These attributes made him an outstanding executive vice president — for, in fact, that is what he was — of the 51st. Because he devoted his time almost exclusively to improving the base and the general welfare of the men, he was admired by most. But he was not all sweetness and light; he was tough when toughness was called for, and he was always ready to argue his point. In fact, there was little Schinz enjoyed more than a good, loud argument. It so happened that Gabby was of like mind. The two men spent many evenings pounding tables and trying to outshout one another. The tigers used to drop in to watch the show because more often than not it was informative: the subject usually concerned new ways to kill a MiG or improve the F-86 Sabrejet.

In four months and thirty-eight missions in Korea, Al Schinz had bagged one and a half MiG’s, which was good, but not par for the course. He lagged behind his World War II record of four Zeros. One day in late April, 1952, he decided to let his base-improvement projects languish while he concentrated on building up his MiG score. Accordingly, he detailed himself to fly his thirty-ninth combat mission on May 1 — May Day, a special Red celebration day when the Communists traditionally brought out MiG’s in force.

On the appointed day, Schinz was up early. He banged out some necessary paperwork, then hurried down to the briefing room to set up the mission. Three other pilots met him there: Colonel Albert S. Kelly, the 51st Group Commander, and two lieutenants. Kelly, an experienced World War II fighter pilot, was reporting for his first Korean mission. Schinz assigned him to fly his own wing, that is, to fly slightly behind him to make sure no MiG’s got on his tail. The other two pilots formed the second element of the flight.

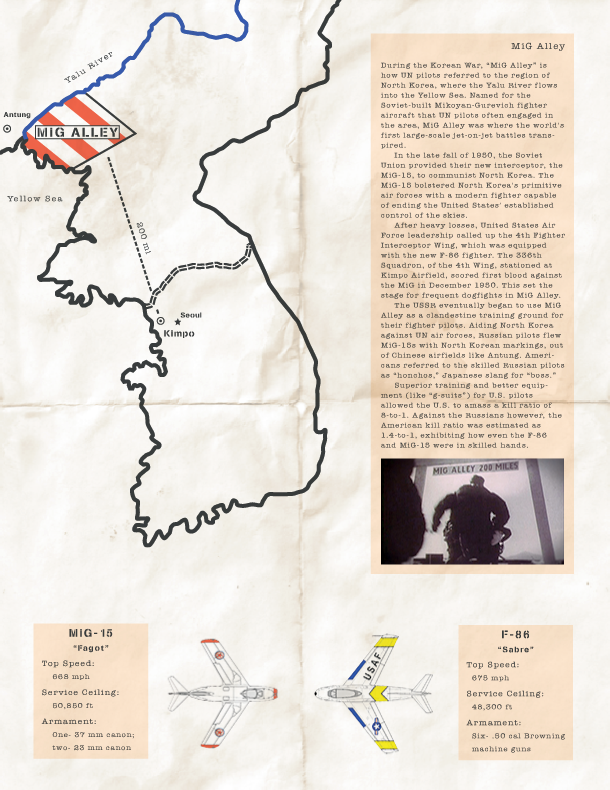

The flight — code named Maple — was plotted with great precision. The planes were to take off and proceed toward the Yalu River, the northern extremity of MiG Alley. As each flight neared the Yalu, it would turn sharply, and search the Communists’ airfield at Antung on the other side of the Yalu for activity — or MiG’s. The flights would be strung out at five-minute intervals, in order to prolong the actual time on patrol at the Yalu. Schinz outlined special combat instructions and selected an escape course that the pilots were to follow if disabled.

Ten minutes before take-off time, Colonel Schinz, “Eagle Leader” of the flight, clomped heavy combat boots up the aluminum boarding ladder of his shiny, swept-wing Sabrejet. Carefully he squeezed his stocky frame into the cockpit. He checked out his equipment: the jet pilot’s acceleration suit known as the G-suit, crash-helmet with radio and oxygen mask attached, a back parachute, rubber dinghy, and an escape and evasion kit containing money, watches, and fountain pens, as well as some Korean money. Unlike most of the tigers, he spurned carrying a gun and a knife.

When the equipment checks were completed, Schinz, via radio, contacted Kelly and the other two men parked in the jets on the ramp near him.

“Start engines,” he said. The quiet midday air was suddenly rent by the whine of jet turbines. Ground crewmen pulled the wheel chocks. Yellow generator carts were hurried out of the way. Then, one by one, the jets moved slowly out onto the taxi way. At exactly 12:30 Schinz and Kelly took off. The others followed at intervals as planned.

The “hot” area of MiG Alley was a good half hour’s flight from the 51st base at Suwon, South Korea. Although the F-86’s were equipped with two wing-tip tanks to extend their range, the science of flying to MiG Alley in an F-86 and then stretching fuel in order to have enough to last through a dog fight and still get home was an exacting one. The pilots experimented constantly in order to obtain the most favorable altitude and cruising speed. Often they were not successful; time after time, Gabby’s pilots ran out of fuel on the way back from MiG Alley and came home “flamed-out,” making dead-stick landings .

Shortly after Schinz and Kelly reached the Yalu, they were joined by the second element of the flight. All seemed quiet as the jets cruised along at 30,000 feet, searching for MiG’s below. But the peace was soon disturbed by a staccato radio report from one of the men: “Sun glints at two o’clock high.” This was bad. The sun glints were MiG’s. They were at 38,000 feet or more. When Schinz and Kelly looked up to confirm the report, they could see the MiG’s clearly. There were 26 to 30 of them, and they were dropping their silver, bomb-shaped wing tanks, preparing for combat. They could tell by the flashes of red and yellow at the noses of the MiG’s that the Communist pilots were already test-firing their guns.

Maple flight was in a bad position, cruising slowly under the MiG’s and with wing tanks still attached. Schinz barked into his radio: “Clean ’em up.” The F- 86’s toggled their tanks, and, at the same time, pushed the throttles to full power. It was too late. Four MiG’s came in from above, nose guns flaming. Kelly, who saw them first, yelled over the radio: “Break right.” This was a signal to Schinz to turn right sharply in order to get out of the path of the diving MiG’s. Schinz and Kelly, now separated from the other element, turned. It was then that Kelly noticed that his right fuel tank had not jettisoned. He pulled the toggle switch again, but the tank would not drop.

The Sabrejets leveled off, and at that instant Kelly spotted two more MiG’s, below, at about 18,000 feet. He reported the fact to Schinz who immediately dropped the nose of his jet and dove toward the planes. Kelly followed — though the obstinate wing tank reduced his speed considerably. Schinz fired a few rounds at the two MiG’s, but they climbed skyward at a fast rate and were soon out of range. As the two F-86’s made a wide turn to pick up speed, Kelly spotted two more MiG’s beneath them. Once again, Schinz turned the Sabrejet toward the earth.

Confident that no MiG could “bounce” them while in such a fast dive, Schinz momentarily took his eyes off the MiG’s below to make sure Kelly was in proper position. But in the split second required to make this check, he lost sight of the MiG’s. Evidently he had pulled the nose of the plane up too far. He called Kelly on the radio: “Do you have them in sight?” Kelly did not; moreover, he had other news. Four more MiG’s were now on their tails, with guns firing.

Kelly shouted, “Break right.” Schinz did not respond. Kelly repeated his call.

Schinz returned, “Kelly. Is that you calling me?” By now, the airwaves were full of chatter and static.

Kelly said, “Roger. Roger. Break hard right, Al. I’ve got four right on my tail and they’re closing fast.”

Schinz replied, “O.K. I’ve got you.”

The MiG’s had closed to two hundred yards. Kelly was in trouble, a sitting duck with the hung tip tank. Both Sabrejets twisted into a hard right turn. They could not hope to outrun or outdive the MiG’s, so they did the only thing they could do: tried to outturn them. The force of the turn was considerable. Schinz’s head was mashed up against the side of the cockpit. He lost sight of Kelly. After a 180-degree turn, he called, “Are you with me?” He thought Kelly said, “I am right behind you,” and he rolled out of the turn.

But Kelly was not behind Schinz. With his hung-up wing tank, Kelly elected to remain in the severe turn, in order to shake the MiG’s. In fact, he flew in a complete circle three times. Meantime, the MiG’s got on Schinz’s tail, and Russian made 37-mm. tracers began to rip into his fuselage and wings. Schinz turned the Sabrejet into a severe split-S, calling on the radio, “Who is shooting at me?” He was upside down, and pulling through the maneuver when he noticed a light on the dashboard warning that the hydraulic system was out of order. This disturbing development was followed by an even more serious one: a dazzling red light signifying fire in the tail pipe lit up the cockpit. The question of just who was shooting at Schinz became academic; the aim was very good.

The jet dropped to 2,000 feet. Schinz said to himself, “Pull out and get some altitude before you lose control.” As he rammed on full power, the jet spun crazily back up to 8,000 feet. At that precise instant, the rudder pedals became “Able Sugar” (completely useless), and the joy stick could not be budged either forward or aft. The jet was out of control; a fire was raging in the tail pipe. Al Schinz began thinking of escape.

Fortunately, the controls of the disabled jet had frozen while Schinz was heading south toward the sea, along the prescribed safety route. As he sped along through the air, the plane jerked violently up. Schinz put both hands and feet on the stick and pushed. Still it would not budge. The plane stalled; the nose dropped. Schinz tried, without success, to pull back on the stick. However, he discovered that by speeding up the engine, he could raise the nose. But he was unable to find a power setting at which the plane would level off, neither climbing nor diving . Consequently, he flew along as though on a roller coaster, dipping up and down.

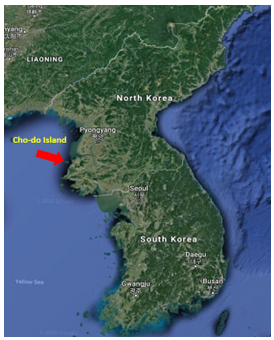

At first, Schinz was confident that he could porpoise along in this fashion long enough to reach the Air Rescue Outpost on Cho-do Island, the planned escape procedure. Accordingly, he called on the radio, “Maple flight, this is Eagle Leader. I’ve been hit and I’m going to try to make Cho-do.” There was no reply. He repeated the call. Again silence. He then switched to the D-dog channel and threw his IFF (Identification, Friend or Foe) from the stand-by to emergency position, hoping that the ever-alert Air Rescue Service would hear the emergency broadcast and fix the location of the aircraft by radio. Too late, Schinz realized that all his radio equipment was out of order, and that in the confusion and speed of combat, the other members of Maple flight had lost him.

The jet yo-yoed southward over the Cholsan Peninsula, going nose-high into a stall, falling off, and then leveling again, as Schinz poured on the power. In each gyration, the jet lost about 2,000 feet altitude. After the second giant porpoise, he realized that he did not have sufficient altitude to reach Cho-do. Quickly he changed plans: he would bail out of the crippled jet near one of the islands off the coast; then, when the search planes came, he would signal to them via his small, two-way URC-4 radio. Schinz was sure of one thing: he was not going down in North Korea and risk being captured.

Soon the jagged end of the peninsula passed beneath the swept wings of the jet, and he was flying over the Yellow Sea. He carefully searched the area below for an island that would suit his purpose. He did not have long to look because by then the jet had descended in stages to 1,500 feet. There was not sufficient altitude to perform another porpoise. It was now or never.

At that moment, the jet flew over a rather large island. In a quick look, Schinz spotted a village on the northern end and two reefs on the south that appeared to be unoccupied. He decided to bail out over the deserted reefs. With the plane climbing up on its last yo-yo, he put his feet in the stirrups of the ejection seat, pulled the left-arm rest knob, then the right knob. The cockpit canopy blew off. He glanced at the dash board, noted that his air speed had fallen below 200 knots, and that his altitude was below 1,000 feet. He fired the ejection seat and hurtled out and upward into the air.

In the confusion, Schinz popped his chute before releasing the heavy ejection seat to which he was still strapped. Ordinarily such an error is fatal, since the parachute is not strong enough to withstand the initial shock of both man and seat. Luckily, the parachute held, long enough for him to correct the mistake. He watched as the seat fell away and splashed into the water not far from the spot where the plane itself had crashed. Then he realized he had not yet removed his helmet and oxygen mask. These were discarded quickly as he made advance plans to fall into the water.

Schinz was not worried. He knew that hundreds of successful parachute landings had been made in the water. Moreover, only a week before he had watched an Escape and Evasion movie that told in vivid detail the techniques of such a landing. He unsnapped the buckles on his parachute harness, sat well back, and began opening the rubber dinghy. As he spilled easily into the cool, but not cold, water, about one hundred feet south of the island and precisely between the two deserted reefs as planned, he was a model of preparedness.

Once in the water, Schinz inflated his yellow Mae West life preserver. Noting that the bright orange and white parachute billowed across the water, he decided to try a technique he had seen in the movie and use the parachute as a spinnaker to sail himself toward the island. He grabbed the top risers to help fill the chute with air. But within seconds, Schinz’s legs were tangled in the bottom risers, a situation, the movie had warned, that should be avoided at all costs. The parachute col lapsed and began to sink slowly, carrying Schinz under with it.

He fought his way up for a gasping breath, then went under again. As he tried to extricate himself from the tangle of shrouds, he succeeded only in getting more deeply entwined. Then he thought of his dinghy again. He groped for the cord on the CO2 bottle which, if pulled, would inflate it. Five minutes later, after more dunkings in which he swallowed a considerable amount of salt water, Schinz located the CO2 lanyard and gave it a pull. The dinghy inflated with a hiss.

Now survival depended on one strategy: getting into the dinghy. Schinz tried to climb aboard. Entangled as he was in the shrouds, it seemed impossible. After several attempts, he was ready to give up. Then he had a new idea: go in feet first. Slowly he maneuvered the dinghy into the proper position. Then he put his feet into the small end and carefully inched his legs upward. With a final lurch, Schinz pushed his buttocks up onto the edge of the dinghy. At that moment, the craft tipped over.

He plunged back under the water. The dinghy landed on top of him. Clawing his way to the surface, he managed to right the raft once more. This time he determined to go slower. Inch by agonizing inch, Schinz edged his legs into the bobbing dinghy. Most of the time, his head was under water. Finally, on the verge of losing consciousness, he made it. Quickly he buttoned up the kayak-like canvas apron; then put his head down and rested.

As he lay there thinking, he made two mental notes: one, henceforth, he would always carry a knife, and two, he would tell the escape and survival people that using the parachute as a sail was dangerous. With some justification, he concluded that a man should disengage himself completely from the parachute on hitting the water.

When he regained some of his strength, Schinz began untangling his legs and body from the parachute shrouds. After a few minutes he pulled the chute clear of both himself and the dinghy. Since he wanted to save the brightly colored chute as a distress signal, and did not have room for it inside, he tied it under the dinghy and let it trail in the water. Then he took an inventory of his rescue equipment. It included the URC-4 two-way radio, two night-signal flares, dye markers, and shark repellent, which were fixed to the Mae West. The Escape and Evasion Kit containing the things he might need most on land had not been fastened to his parachute harness, and it had sailed away when he bailed out.

Once settled in the dinghy, Colonel Schinz got out the URC-4 radio, plugged in the battery, and extended the antennae. Confident that the planes in Maple flight were searching down the escape route, he called into the miniature speaker to try to attract them. There was no response. Was the radio damaged? Schinz tinkered with the insides, pulling and pushing the wires and tubes. It was completely dead. For the first time he began to worry. Now he had no radio to call the planes down to him, only a signal mirror. In vain, he searched the skies for signs of friendly fighters.

He then decided to paddle to shore. As he wedged himself into a comfortable position, he made an alarming discovery: the paddles that should have been provided with the dinghy were not aboard. Flailing his arms, he tried to propel the craft to the island. It was a losing battle. A strong tide was carrying him out to sea. The forgotten parachute dragging underneath helped the current to tug at him. An hour of this was enough to exhaust him. He collapsed and slept as the dinghy drifted away from the island and out to sea.

The sound of breakers woke him. It was dark, and his illuminated watch dial told him he had been asleep seven hours. Now the tide was flooding, and he was drifting slowly up to a rocky beach. He could not tell how soon the tide would ebb again and when the current would wash him out to sea once more. He remembered the dragging parachute and released it. In the process, he discovered that a special survivor’s kit was also hanging under the dinghy. He pulled that into the dinghy and started paddling with his arms once more.

A short time later, Schinz heard the noise of airplane engines in the night. As the plane came closer, he could tell by the sound that it was an Air Force B-26. He began to have hope once more . It winged in low, right over him. He grabbed one of the flares and ripped off the top. But it fizzled and went out. The plane flew straight on over the horizon. He cursed softly to himself and began paddling again toward the dark land mass.

It took five more hours of arm flailing before Schinz and his rubber raft bumped onto the rocky beach of the island. At first his legs were so stiff from the hours of exposure in the cramped dinghy that he could not stand up. But he finally managed to stagger ashore, dragging the dinghy with him. Remembering the deep Korean tides, he climbed up rocks and cliffs until he reached the timber line twenty-five feet above the beach. He wedged the dinghy between some rocks, climbed in, pulled the canvas cover over him, and dozed.

The sun woke him from his damp, cramped sleep. For a long while he sat still in the dinghy, staring at the rocky beach below, watching the spray slap over the boulders and whoosh in and out of the rocky caves. Above him rose the black heights of a cliff. He tried to keep his mind fresh and preoccupied by watching nature at work around him, but inevitably his thoughts turned to himself and his unenviable predicament. Was the island occupied by Communists? Was it inhabited at all? If so, could the rescue planes land safely and pick him up? Was there, on this barren spot, enough food and water to sustain life? Dare he light a fire to get warm and dry his clothes? How would his wife Lorayne, his young son and daughter feel when they received the “missing in action” report?

The last thought stirred Schinz into action. He had better get back to the base quickly, he thought, before his family had suffered unnecessary anguish. He unsnapped the dinghy cover and crawled out. The cold salt water rolled off his olive drab GI trousers and shirt. He stamped his boots on the rocky ground, then took off his soaking flying jacket. He was shivering from head to foot, either from cold or exhaustion, or a combination of both. Would he become ill from it? Schinz decided not to chance it. He would build a fire and dry his clothes, even at the risk of alerting Communists who might be on the island.

Suddenly, he realized that he had no matches. Even if he had, they would have been ruined by the water. Then he remembered his Zippo lighter. He reached in his pocket and pulled it out. Salt water poured out as he snapped back the chrome-plated top. Schinz was heartsick. The lighter seemed ruined. He fell to his knees and sobbed. He was not a particularly religious man; but he broke into prayer. He asked the Lord to make his lighter work in spite of the salt-water dunking. Then he ran about picking up small twigs. He even found a piece of paper. He put the lot in a small pile, knelt down, and hopefully flicked the wheel of the lighter again; it burst into a long, yellow flame. “A miracle,” Schinz cried aloud; and as soon as the fire had caught, he dropped to his knees and began praying all over again.

He took off his clothes and hung them by the fire to dry. Then he sat down and waited for the search planes. He was sure they would be coming over soon. He wondered if his small signal mirror would be adequate. He thought of gathering larger logs to throw on the fire to increase its size, but rejected the idea. Instead, as an additional distress signal, he pulled his dinghy out into plain view. He was so certain he would be spotted, and soon, that he did no further long-range planning. He just sat by the fire waiting, occasionally tinkering with the damaged radio or polishing the signal mirror.

No search planes came. By noon, his clothes were dry, so he put them on and started a cautious exploration of his end of the island. It had been twenty-four hours since his last meal, and he was hungry. He found an old, almost overgrown path, and followed it up and down the rocky terrain, laboriously pushing his way through dense willow scrubs. He climbed over the brow of a hill, then dropped flat on the ground, and lay there, scarcely daring to breathe.

Ahead in a small clearing were four thatch-roofed huts. Schinz waited for a sign of life, friend or foe, but there was none. No smoke rose from the roofs. There was not a sound except that of a few birds in the scrub oak in back of him. He circled the huts warily, but still saw no evidence of activity. Finally, he walked straight into the village.

The huts were abandoned and littered with filth. Some were partially burned. The area around the village was dotted with slit trenches and abandoned gun emplacements. He poked through the huts. He found GI cans, punctured by bullet holes. The soldiers who had occupied the village were U.S. or Korean, he concluded. From the condition of the debris Schinz judged that the troops had been gone for several weeks or perhaps even longer.

By then, he was beginning to feel weak, so he made plans to camp in the abandoned village. He selected a small lean-to, cleaned out the filth, and covered the ground with cornstalks and grass from the nearby field. He named the lean-to “Headquarters.” Then he gathered some wood and just outside “Headquarters” built a roaring fire. He stretched out on two empty rice bags that he had found while gathering the wood, and concentrated on regaining his strength. But he became very thirsty, and soon he was on his feet again, searching for fresh water.

He found a stream on the far side of the cornfield. Then he walked back to the village and searched for a vessel in which to carry the water. In one hut he found a rusty tin can. He took the can to the stream and meticulously cleaned it with rocks and sand. Then he carefully strained some water through his handkerchief and carried it back to the fire. He boiled the water for about fifteen minutes, to make sure it was sterile. Then he let it cool, sat back on his rice bags, and took a deep swig.

The water satisfied his thirst but did nothing for the hunger pains that were beginning to well up in his stomach. Soon Schinz was walking again, this time in search of food. In the cornfield he found a few unharvested ears of corn. Near the edge of the field he found a few spring onions as well as a patch of dandelion greens. He gathered up a handful of each and went back to the fire. He put the corn kernels, onions, and dandelions into the scoured cans and carefully boiled the lot into a crude succotash. The corn was bitter and hard, the onions tasteless, and the dandelions stringy, but it was his first meal in twenty-four hours, and it revived his body and spirits.

All the while, Schinz kept one eye cocked on the sky. He was puzzled by the lack of air activity. Where were the search planes? Where were the boys from the base? Had they left him to sweat it out alone, without even a cursory search? Then he began to worry again about the inadequacy of his signal equipment, and decided to make an SOS. The best he could do that afternoon was to fashion some chunks of red clay roughly into the shape of an SOS. But as he finished the work, he realized that it was so small and drab that it would never be seen from the air. His spirits began to fall once more. By nighttime, they were very low. No aircraft had come over the island all day.

Shortly after dark, Schinz took his two rice bags and crawled into the lean-to. He was very tired and anxious to sleep. He lay down, carefully spreading the bags over his shivering frame, but he soon found they afforded little or no protection from the cold night air. He slept for an hour, then got up and sat by the fire to warm up. Then he crawled back into the lean-to.

As the night wore on, the fire began to flicker and die out. Schinz took out his lighter to make sure that it still worked in case the fire went out altogether during the night. He was startled to discover that the Zippo would no longer light. An agonizing thought flashed through his mind: if he was to have fire at all in the future, he must keep the present one going. Quickly, he gathered a large pile of firewood and fanned the fire’s smoldering embers into a bright blaze. To his other problems, Schinz now added that of maintaining a constant supply of firewood.

At daybreak, Schinz crawled out of the “Headquarters” lean-to, cold and stiff. He looked up at the sky. The weather was clear. The search planes were sure to come over soon, he thought. His mind turned to food; he had better try to find something more to eat. He stumbled down to the stream, filled his can with water, and on the way back to the fire picked a handful of onions and dandelion greens. While he watched his breakfast boiling in the rusty can, he conceived the idea of keeping a record of his experiences. The information might later be useful to the Intelligence division. He pulled out a red grease pencil and scratched a few words in a small leather bound notebook that he kept in his wallet.

After breakfast, Schinz went exploring again. He had begun to worry about the possibility of Communists on the island, and he did not want to be surprised. He pushed his way through the thick underbrush and rough terrain. Soon he reached a point where he could see a large part of the island, especially the main village in the north. He watched the village for three hours. Satisfied that it also was deserted, he then hiked back to “Headquarters.” On the way home, he stumbled across a magnificent treasure: three small packages of Army rations!

For lunch that day, his sparse fare of corn-onion-dandelion succotash was garnished by hardtack and crackers from the ration packages. He ate sparingly of the rations in order to stretch them as far as possible. That afternoon, his mind once again turned to signal devices. He polished his mirror and thought of ways to build an SOS distinct enough to be seen from the air. But none of his ideas seemed practicable. He examined his one remaining flare and wondered if it would fizzle like the other. Then an idea occurred: why not build a nighttime SOS out of grass and cornstalks which he could set on fire if a plane came over and the flare fizzled? He went to the clearing and gathered up a huge pile of cornstalks and arranged them in the shape of an SOS.

After the usual supper, Schinz crawled into the lean-to. Before going to sleep, he jotted down in his notebook: “It looks as though the whole island is vacated.” But he was not sure. In the middle of the night, he jumped awake as a B-26 night intruder roared low over the island. Racing out of the lean-to, he fired his second flare. Three bright red balls of fire soared into the sky. The plane droned steadily off into the darkness.

Schinz began his fourth day on the island by watching a flight of planes passing over at very high altitude. He was certain that the B-26 of the night before had seen his flare and had reported the fact to Air Rescue. He was impatiently awaiting the arrival of a helicopter and jotted in his diary: “F-86’s high overhead. Why no chopper?” After breakfast, while keeping alert for signs of air activity, he began his daily search for food. In one of the half-burned huts, he found a large pile of raw cotton. He was wondering what use he could make of the white balls when the thought suddenly occurred: “What a great SOS I could make with this!”

Schinz scooped up some of the cotton and put it in a wicker basket that he found in one corner of the hut. In a few minutes, he was on his way out to the cleared field. He dumped the cotton on the ground and then went back for more. Soon he had enough to begin the SOS. He sat on the ground, carefully stretched out each of the cotton balls and then padded them into the earth. It was tedious work. After a few hours, the letters measured about three by five feet. Satisfied, he went back to camp, cooked the usual meal, and, though his back and hands ached terribly, he comforted himself with the thought: “The chopper will see that with no strain.”

That night as he rested in the lean-to, he heard the distant throb of airplane engines. He rushed from the lean-to, grabbed a burning stick from the fire, and ran to his cornstalk SOS in the clearing. He lit the first “S,” and as it crackled into flames, he moved to the “O.” But, by the time the “O” had caught, the “S” had burned out. As the plane flew directly overhead, Schinz ran back to the first “S” and tried to light it again. While he was thus engaged, the “O” fizzled out. He ran to the last “S,” lit that, and then relit the “O.” Then both letters burned out rapidly. Schinz stood looking helplessly up into the sky as the plane flew on without a sign of recognition.

He walked slowly back to the lean-to, sat down, and wrote in his diary: “A hell of a good fire but a complete failure as an SOS.” He then turned over in his makeshift bed and sobbed.

The next morning, after breakfast, he walked out to inspect his cotton SOS. Now it seemed very small. He took out his diary and wrote: “I’m tired of you guys not seeing my SOS. I will build a new one with letters 25 feet by 15 feet. That should be big enough.”

This was a formidable goal. Hauling the additional cotton from the hut, then sitting in the clearing hour after hour padding each small piece into the ground proved to be very hard work. But Schinz was a determined man. In the middle of the “O,” he began to run short of cotton so, when completed, the “O” and last “S” were somewhat smaller than the first “S.” As he finished the sign, Schinz jotted in his book: “I am beginning to learn the real meaning of the word ‘patience.’”

In the afternoon, Schinz went exploring again. He made a happy find on top of a hill; there on a vantage point with a view of the whole island, somebody had left a decrepit but still comfortable old swivel chair. Tilting and swinging around on his creaking throne, Schinz smiled as he surveyed his little world. Across the water, he could clearly see the Communist mainland. But the island itself seemed to be completely deserted.

He liked the swivel chair so much that he heaved it to his back and stumbled down the hill with it. But his marginal diet had weakened him more than he realized; by the time he reached the lean-to with the heavy burden, he could hardly walk. Now he saw that he must husband his waning strength; he could not afford to waste it transporting luxuries like swivel chairs. Just the same, his diet of corn and dandelion greens seemed to taste a little better that night as he ate them while sitting in his comfortable chair.

After supper Schinz began to think again of his night time SOS. He needed some means of signaling the aircraft that flew over in the dark. Perhaps the cornstalks would burn better if protected, he thought. He went out to the clearing and dug long ditches, roughly spelling out SOS. Into the ditches, he carefully piled more cornstalks. Later that night when another B-26 flew over low, Schinz ran out and lit the SOS fire. It burned satisfactorily, at least much better than the previous one. Moreover, the moon was bright, and there was a chance that the pilot had seen the white cotton SOS, too. Always the optimist, Schinz took out his diary and wrote: “A B-26 flew over and saw my sign….”

He was up early the next morning, awaiting the chopper. None came.

Biting his lips in disappointment, Schinz sat in his swivel chair, staring sadly at the fire. What would he do? A thought occurred: perhaps it would be wise to move into the main village if it was indeed deserted. But then, what if Communists came over from the mainland? Would they not go first to the main village? Would he not be safer on this remote end of the island? What of the SOS that he had so painstakingly built? Had he not better stay near it in case it was spotted by friendly planes?

He thought about these things for a long while. He weighed them against certain realities he faced: a rapidly dwindling supply of firewood and an even more rapidly dwindling sup ply of food. Schinz had almost completely torn down all the huts in the village in order to keep his fire going. His three small packages of Army rations had lasted seven days, but now they were gone. Perhaps there were others in the main village. He was certain to find a supply of firewood.

At length Schinz decided he would hike over to the main village anyway, just to look it over. He might be lucky enough to find some food. He climbed up the rocky hills, slid down steep slopes, panting and sweating, resting often to gather strength. After a few hours of this, he came within a quarter of a mile of the village. He found a hill from which he could see the area plainly, lay down on the ground , and watched.

The village was larger than he thought. It consisted of about fifteen large huts or houses and one larger building that looked like a schoolhouse or a church. Off to one side of the village, he could see a field that had been under cultivation. There were cornstalks grouped together on one side of the field; dried-up cotton plants on another. Farther along, he saw a rice paddy. There was no sign of life in the village.

Schinz crawled closer. Again, for a long while, he lay on the ground scrutinizing the huts. Finally, he cupped his hands to his mouth and shouted. He was surprised at the strength of his voice as it echoed through the village. He shouted again, but there was no answer. He saw no one come from the huts.

He waited a few more minutes, then got up and walked into the town.

The village was completely deserted. The ground was littered with filth. It smelled of death and disease, so badly that for a brief moment, Schinz thought he would become sick at his stomach. He clamped his thumb and forefinger over his nose and pushed on in search of food and water. The huts seemed well built. Large timbers supported the thatch roofs. The walls were thick and firm. But the floors of the huts were covered with foul refuse, including the gaunt remains of several cats. Big rats scampered about when Schinz opened the doors. He reckoned the village had not been inhabited for at least six months.

Schinz could not remain in the village long. The stench was overpowering. Finding neither food nor water, he soon hurried out and began the long hike back to his “Headquarters” lean-to. He was now convinced that, if nothing else, the filth of the village was sufficient reason to keep him from moving there. He would just somehow make do at his original camp and hope that he could stay alive until the rescue planes spotted him.

He made some minor improvements at the “Headquarters” camp. The SOS sign was enlarged. He returned to the beach and dragged the dinghy back to camp. He placed it inside the lean-to and used it as a bed. It was not comfortable, but he could at least button up the cover at night and keep warm. The dinghy also yielded a surprise: a water-soaked package of cigarettes. Schinz spilled the tobacco into a can in order to dry it out, then with some Korean tissue paper “rolled his own.” He rationed himself: one cigarette per day, which he smoked while sitting in the swivel chair in the evenings after supper.

Feeling the need for a weapon of some sort and having little else to occupy his time, Schinz set out one morning to make a slingshot. He cut a fork from a small willow tree and trimmed it to the right size. Then he ripped a piece of rubber from his G-suit, which he had found in the dinghy. The G-suit rubber turned out to be “inferior” as he noted in his diary. So he cut open a bladder of his Mae West. This rubber was more than suitable. From a pocket flap of the preserver, he tore a small piece of canvas to serve as the rock holder. The finished product was almost of professional caliber. It would come in handy later.

In his daily wanderings about the camp, Schinz had begun to collect a small inventory of usable junk and equipment. One day he found an old rusty shovel. Another day he discovered a knife. He uncovered a GI can that was not punctured by holes. He unearthed a few dishes, and an “A” frame, a device that Orientals strap on their backs to help carry heavy loads, which was very useful in collecting firewood. The most heartening discovery was made on the twelfth day.

While foraging the countryside for firewood and anything else of value, he came across a large bag of dried beans in a field. He put the bag on the A frame and packed it back to camp. Later, he found that by soaking the hard beans in water for about a half day, they became pliable and suitable for cooking. Afterward, Schinz put a few of the soaked beans in the tin can and boiled them for another half day. The result was less than sensational but for Schinz the beans added a new course to his monotonous diet of corn, dandelions, and spring onions. The “broth” or juice in which the beans were cooked was especially tasty.

On the fourteenth day, Schinz decided to take a bath. He hauled some extra water from the stream and poured it into the dinghy, which he had dragged into the sunlight. Then he took off his clothes and washed. After his bath, he poured out the water, then stretched out on the dinghy to bask in the warm sun. He looked down at his toes. In doing so, he noted with some alarm that he could not see his stomach. He stretched his hands around his body and discovered that his finger tips touched. He estimated that his waist, which was formerly thirty-six inches, was now about twenty inches, and that he had lost fifty pounds.

This discovery had a devastating effect on his morale. It was not that he was getting thin. He knew that all along, because his belt was getting loose. It was the actual dimensions of it that scared him. Fifty pounds! It seemed clear to Schinz that he was slowly starving to death. Lately he had been getting weaker and weaker.

The blow to his morale was particularly untimely because by now the firewood in the “Headquarters” village had been consumed. In order to keep the fire going, Schinz had to go on long hikes from the camp in search of wood, staggering all the way under the heavy A frame. Moreover, lately the wind had been blowing with some force, and his cotton SOS was frequently scattered across the field. He had to spend many hours gathering up the pieces and resetting the letters. It seemed to him that the weaker he got, the harder he had to work .

Two weeks had passed. An occasional plane had flown over, but none reacted to his SOS. It was plain to Schinz that he was getting no place fast. If anything, he was losing ground. What could he do? He thought briefly of getting in the dinghy and paddling to the Communist mainland. With this in mind, he made two crude paddles. Later he discarded the idea: the thought of deliberately giving himself up was repulsive.

That afternoon, Schinz took a long hike in the direction of the main village. His spirit was broken; he felt weak, unable to go on. As he trudged along the trail, he unconsciously fell into prayer. He asked God to help him out of his dilemma. Then, within a very few minutes, Schinz came upon a large cave that he had not noticed before. He entered cautiously, and to his surprise, found that it was filled with bags of cotton! Enough to build a much bigger and better SOS, he thought.

That night after supper, Schinz sat in the swivel chair thinking. The discovery of the new batch of cotton, he decided, was an omen he could not ignore. In fact — coming so hard on the heels of his prayers — Schinz became convinced that God was now directing his destiny. Obviously, the only way out of his predicament was to build a bigger SOS. God had supplied the cotton, and it was up to him to do the work. Schinz was charged with renewed hope.

But the cave with the cotton supply was a long way from his “Headquarters” camp. It was, in fact, closer to the main village. Should he now reconsider moving to the village?

Schinz remembered the dead cats, the rats, and the stench and instantly rejected the idea. But then he considered the great supply of firewood in the village. Perhaps somewhere in those many huts, there was some food he had missed on his first inspection; food that would give him strength to build the new SOS. But what if he was discovered in the village by Communists? To hell with that, he thought. Mere survival was now uppermost in his mind. Before going to bed, he wrote enthusiastically in his diary: “I am going to start all over at the new camp. And I am going to be home by June.”

Having made the decision to move, Schinz was up early the next morning to get on with it. But it proved to be a much greater task than he had anticipated.

First, he gathered up all his equipment: the dinghy, Mae West, G-suit, a handful of corn, some old rags, his bag of beans, dishes, tin cans, tobacco, slingshot, and the GI can, and carefully strapped it onto the A frame. Then he knelt down and backed his arms into the A frame, and slowly staggered to his feet. As he was about to start out, he remembered the fire. He had no matches . How would he start a new fire in the village?

He put the A frame back on the ground while he pondered the problem. The only solution that he could see was to transport a portion of the fire to the main village. In what? Could he carry the fire and the A frame at one time? Schinz thought not. But was he capable of making two trips back and forth to the main village? He was doubtful but decided to risk it anyway. Accordingly, he pulled a burning, six-foot branch from the fire, and began hiking toward the main village.

When he arrived, the brand was still burning. He laid it on the ground, then gathered more wood, and soon built a roaring fire. Then he started back for the “Headquarters” camp. Halfway home, Schinz began to feel dizzy and weak. He stumbled, fell, struggled to his feet, and then fell again. Finally, he crawled into camp. He plopped down alongside the fire, and was soon eating beans, dandelions, corn, and onions, which he had thoughtfully put on to boil before leaving for the main village. He drank the broth, then lay down and slept heavily.

Several hours later he awoke. He got up and looked skeptically at the A frame. Could he make it to the main village once more? Why carry all that stuff along? He convinced himself that for survival he would need every item. Finally, he got down on his knees, backed once more into the frame, struggled to his feet, and began the long, winding journey to the main village. He fell often, sometimes forward on his face. All through the trip, he prayed softly, repeating his small repertoire of prayers over and over. He covered the last half mile crawling on his hands and knees. When he finally reached the fire, he threw on a few logs to keep it going, then collapsed. As his mind drifted off into space, he wondered vaguely if he would ever wake again.

When Schinz awoke the following morning, he was so weak that he could hardly move. He believed that he was near death. When he finally got to his feet, he turned his eyes skyward and once more prayed. This time he asked God for food. When he finished praying, he held his nose and walked into the nearest hut. He could hardly believe what he saw: twenty-five bags of raw rice that, somehow, had not been devoured by the village rats. “Another miracle,” he said to himself, and he thanked God. In one corner of the hut, he found a stone grinder and a sifter, and after fiddling with the devices a few minutes, he learned how to use them to separate the rice kernels from the husks. Soon he had all the clean rice he could possibly eat.

Now he needed water. Holding his nose again , he wandered through the stinking village. He found a stream, but it was dirty, and he was afraid to use the water. Once more, he appealed to God. Not long afterward, he came upon a burned out hut that he had not seen before. He peered inside. There was a deep-water well. Almost delirious with joy, Schinz fell to his knees in prayer. Then he drew a bucketful of water and hurried back to the fire. From his A frame, he selected two cans, one slightly larger than the other. He put water in the larger can and then floated the smaller can on the water. The result was a crude double-boiler. Soon the rice was cooking. When it was done, Schinz ate like a pig. With his stomach full for the first time in two weeks, he slept soundly.

When he awoke again, it was late afternoon. Feeling much stronger, he got up and began making plans for a permanent camp. If there had been any doubt in his mind about the wisdom of remaining in the smelly village, the discovery of the rice had erased it. He decided to move into one of the huts. He selected the schoolhouse because it was the best built of the lot and had a very large fireplace. He cleaned out the dirt, moved his fire into the fireplace. Before going to sleep that night, he ate more rice.

The following morning, Schinz ate a rice breakfast and, then, with his strength rapidly returning, set off on a pressing chore — cleaning up the village. He collected the remains of the dead cats, dragged them out of town into a field, and buried them. Then he swept other filth and refuse aside. He got a stick and chased many of the big rats into the fields. He worked especially hard on his schoolhouse living quarters, and soon the building, while not absolutely spic and span, acquired a military neatness, as Schinz carefully arranged the equipment from the A frame about the single room.

In the afternoon, he ground more rice. “This is recreation, not work,” he noted in his diary. Then, with the stench rapidly abating, he went off in search of other food. In one hut, he found several strings of seed corn hanging from the ceiling. Then, curious about the neat shocks of cornstalks in the field, he went out and ripped one open. Inside, he found green stalks, laden with big, fresh beans. That night he cooked a veritable banquet on the schoolroom hearth: rice, corn, fresh beans, onions, and dandelion greens. Afterward, as he puffed on a hand-rolled cigarette, he wrote cheerfully in his diary: “In much better spirits.”

Having regained his strength and self-confidence, Schinz now turned to the big job: building the giant-size SOS. He went to the cave and examined the cotton. He found it in excellent condition and estimated there was more than enough to build the SOS he had in mind. Then he climbed a small hill and surveyed the clearing between the cave and the village. He decided to put the letters “SO” in the clearing near the cave, and the other “S” on the opposite side of the village. He lost no time in getting to work.

As he had done so many hours before, Schinz sat patiently on the ground and unwound each of the small balls of cotton and pushed them into the earth. Hours, then days, went by, as he, little by little, created the giant-sized cotton letters. It was dull, monotonous, but necessary, work. He struck up a friendship with the birds that flitted back and forth across the field, chirping and tweeting. He chatted absently with one of the birds, which he believed was a cuckoo: “I might be cuckoo but at least my name isn’t cuckoo. My name is Colonel Al Schinz, USAF.” When the SOS was completed, the letters measured forty-five feet long and fifteen feet wide. Schinz was sure that his sign could easily be seen from the air and that he would soon be rescued.

Having completed the big job, Schinz set about to make his life on the island more comfortable. He found a table and dragged it into his schoolhouse quarters. Oddly, he came across another swivel chair. It soon occupied his favorite spot on the hearthside. To his small collection of utensils he added a fork and a cup. Then, with a chisel and hammer that he found in one of the huts, he cut a piece of aluminum from a B-26 drop tank and beat it into the shape of a spoon. One evening, he jotted in his diary: “Today I found a fishhook. I am going to try it tomorrow.”

Next morning, Schinz poked around the village looking for earthworms. He found none. Finally, he collected a handful of corn and then trudged down to the rocky beach, looking for a likely fish hole. He baited the hook with a kernel of corn and threw the line into the water. He waited for a bite, but there was no activity. Finally, he became bored. He tied the hand line to a bush and began exploring the beach. Not far from the fish hole, he discovered three large oil drums that had washed ashore and were half buried in the sand.

Schinz ran to the drums and, brushing the sand away, read the English markings on the outside. He ascertained that one barrel contained 100-octane aviation gasoline, the others diesel oil. What a magnificent signal fire could be made with the oil, Schinz thought. What a discovery! He ran to the village, picked up his hammer and chisel and two earthen jars. Then he knocked a hole in one of the barrels of diesel oil and filled the jars. Back in the village, he poured the black oil into a GI can. He spent the afternoon shuttling between the village and the barrels. On the last trip, he brought back a jar of gasoline to use as lighter fuel, as an additive to his fire, and as a possible fuel for night signaling.

The following morning, Schinz collected a large pile of cotton and rags and doused the lot with diesel oil. Then, as if on cue, an airplane appeared in the distance. Schinz lighted the oil-soaked rags. Dense, black smoke billowed up into the sky. The plane turned toward the island and came closer. Schinz recognized it as an F-51 fighter. He jumped up and down, waving and shouting. The plane buzzed low over the island, circled, and then bore in again. Schinz waved his arms madly. The plane flew overhead and, to Schinz’s utter amazement, dropped its two wing-tip tanks in the middle of the village. “Are you trying to kill me?” he shouted. The plane flew away and did not return. He cursed loudly, and that night he jotted in his diary: “Guess he thought I was a Korean working up a bunch of chow.”

In the evening after supper, Schinz walked down to the beach to check his hand line. As usual, there was no fish on the hook. The kernel bait was intact and did not even seem nibbled. He dropped the line back into the water and then sat silently staring out to sea. A short time later, out of the corner of one eye, Schinz spied a shape on the water, coming around a rocky bend on the coastline. It was a sailing junk! As it came closer, he could see that there was only one man in it. When the junk was directly off the beach, Schinz yelled to the man. Then he jumped up and down, waving his arms and shrieking. The junk abruptly turned tail and sailed out of sight.

Later that night, tossing on the floor of the hut, Schinz cursed himself for shouting at the junk. If he had remained quiet, or hidden in the brush, he thought, the man might have landed on shore, in which case, he could have ambushed him, stolen his boat, and sailed south to Cho-do. What if he was a Communist? Had he recognized Schinz as a downed airman? Or did he think, as the F-51 pilot probably thought, that Schinz was just another Korean? He was very worried and wrote in his diary: “One man sailing junk passed within one block of the island. My hollering scared him away. Am sure he will report me to the Communists on the mainland.” But, like the chopper, no Communists came.

As each day passed, Schinz became more optimistic about his chances of survival. For one thing, his strength had fully returned. His living quarters, while crude, were not unbearable. Every day he discovered an item or so that added to his comfort or general welfare. His signal devices had multiplied with the discovery of the oil. He now felt that he could easily lure aircraft toward the island in the daytime and that, once there, they would surely see the SOS. He was dissatisfied only with his night signaling devices.

On the morning of May 23, he felt unaccountably optimistic. Before breakfast, he noted in his diary: “I am due to be rescued.” Within a few hours, he heard the sound of aircraft engines. Once again, Schinz raced out and touched off the oil-soaked rags, and again, dense smoke swirled skyward. All day long, aircraft flew over the island. Schinz stood in the clearing, waving a pair of home-made flags. “Lots of activity,” he gleefully noted in his diary. He was so sure that he would be rescued that day that he gathered up all the equipment that he wanted to take back to the base and stacked it in the clearing.

He poured more oil on the rags and waited patiently for the chopper. But none came. He was dismayed. His spirits plunged from the great heights to which they had been elevated to darkest despair. What in the world could the Air Force be doing? he asked. When the sun went down and he knew no chopper would come, he knelt on the ground and prayed. Then, his forehead on the ground, he beat his fists in the dust and sobbed.

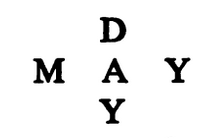

The next morning Schinz reviewed the events of the previous day. Why had he not been rescued? What had he done wrong? Apparently, his SOS was not good enough. Could he make it any larger or plainer? He thought about it all morning, then an idea occurred: build a sign that spelled MAYDAY, the standard international distress call, one used by all Air Force pilots in trouble. That ought to attract some attention, he told himself.

The new sign would require an effort far beyond anything Schinz had heretofore contemplated. He thought of arranging the letters like this:

to conserve cotton, but even so, the sign had a total of five letters. He decided to move into a hut near the field and the cave that contained the cotton supply. It would be less luxurious than the schoolhouse but more convenient, since he would not have to walk back and forth as much while building and “policing” the sign.

Schinz cleaned out the new hut, moved his vital equipment from the schoolhouse, and prepared to begin life anew in his lesser quarters. For the next week, he painstakingly put the mayday sign together. After more lugging of cotton, more packing it into shape, and more cuckooing back at the cuckoos, he neared the end of the job. It is a masterpiece, Schinz thought as he tucked in the last bit of cotton and stood back to admire it.

With the sign finished, his mind turned to other things. He thought about his family. He thought about the Air Rescue Service and muttered some unkind things under his breath. He thought about Gabby and the boys, and wondered how many MiG’s they had shot down by now. But most of all, Schinz thought about meat.

He had been on the island twenty-five days and had had nothing to eat but rice and tasteless vegetables. Some way he had to find meat. There appeared to be one survivor of the island’s former cat population, a scrawny, moth-eaten tomcat that had slunk in and out of the settlement once or twice. Schinz conjured up visions of the cat roasted deep brown and flanked by piles of French-fried potatoes. He decided he would go after that cat.

Next morning, he awoke in bright, hungry spirits. He went to a stream near the mayday sign and dug out a small pool. The water was clear and cool. This was to be the refrigerator: once he caught the cat, he would dismember it, and store the uneaten parts in the cool water. That way, by Schinz’s own careful reckoning, the cat might last a good three days.

He went back to the hut, got out his rusty knife and the slingshot. With great deliberation, he selected about fifty, small, well-rounded pebbles for ammunition. Then he set out on safari.

Feeling not a little silly as he called, “Here, kitty, kitty, kitty!” Schinz tramped through the brush. The cat tentatively stuck its head out of a bush. Schinz tried to ease within grabbing range; the cat took off. The prey seemed actually to be enjoying the game. It would duck around an obstacle, then stick its head around as if to make sure the pursuer was still pursuing. Schinz would try easing the slingshot into firing position slowly so as not to scare the cat. The cat would wait, with an expression that looked like a sneer, then duck nimbly aside. Schinz coaxed, wheedled, swore, cried. For three days this went on, the cat bounding happily around and around him until he staggered and stumbled home to his dinner of dandelion greens.

But then another possibility presented itself. One morning two confused birds flew into Schinz’s hut. They hardly had time to realize they were under a roof before Schinz had streaked across the hut and closed the door. For forty-five minutes he crashed around the little hut, slamming his few pieces of furniture all over the room before he finally caught the birds. He wrapped them in a piece of cloth, took it out to his fire and left it there while he ran for a can of water. Hurrying back, he gingerly unfolded the cloth. The birds had flown.

To prepare for a possible recurrence of the bird incident, Schinz built a crude butterfly net from a piece of fishnet that he found on the beach. Luck was with him. The very next morning two more birds wandered into the hut. Schinz quickly snatched the birds out of the air, and as he noted in his diary later: “Hustled them down to the chopping block for an immediate head-chopping ceremony.” He ate the birds, bones and all.

The taste of bird meat only whetted his appetite. Recalling that he had seen a few snakes on the island, he fashioned a fork out of a long — a very long — stick. Off he went, poking about in the brush and muttering over and over again to himself, “Snake meat is one of the world’s greatest delicacies.” But snakes are even nimbler than cats. After a futile day of snake chasing, Schinz resigned himself to his vegetable diet.

Then a baby wren fell out of its nest near his hut one day. Schinz grabbed it eagerly. The bird cocked its little head, studied Schinz with its big eyes, opened its beak, and chirped. Schinz couldn’t do it, not to a baby. He put it back in the nest.

The next day the baby wren fell out again, and again Schinz put it back.

On the third day, the wren fell out and dropped right at his feet. Schinz looked down at the bird, then up at the sky. “Lord,” he said, “I believe You want me to eat this little wren.” So he did.

The last day of May, at which point Schinz had been on the island thirty days, was one of the toughest. The weather had turned bad, and Schinz had been working feverishly to get firewood under cover. He smoked the last of his carefully hoarded cigarettes and noted in his diary, “went on corn silk.” May 31, he also noted down, is “payday.”

With the weather bad, and no hope of aircraft coming over the island, Schinz dreamed up new projects to keep himself occupied. In the village several days earlier, he had noticed an Army cot minus its canvas. He dragged the cot frame to his hut and carefully dismembered it — no small problem without a screwdriver or wrench. Then he cut off the bottoms of three rice bags and slipped these onto the cot frame.

He sewed the bags into place with some string, then put the cot back together again. He bounced up and down a couple of times to give it a comfortable sag, then laid down for an “operational suitability test” and discovered that it was “quite a sack,” as he noted in the diary.

Next, he decided to make a mattress. In one corner of the hut, he found some cotton from which the seed had been removed. It was very soft and silky. He dumped that into the sagging cot, until it reached the level of the frame. He covered the “mattress” with some rags that he had sewn together to use as a sheet. Then he took four heavy pieces of cloth that he had found in the village and sewed them together. This served as a blanket. Finally, he took a large piece of burlap, doubled it over, placed a six-inch layer of cotton inside, and sewed up the open ends of the burlap. This was his comforter. As a crowning touch to his bed, Schinz added a new find: a mosquito net.

Schinz was extremely particular about his clothes and personal hygiene. He bathed often and boiled his clothes every third day. He was choosy about where he slept, and as a result, had thus far escaped lice and other vermin. He took good care of his shoes. He treated them every third day with the diesel oil. He kept his gloves repaired with a needle and rice thread that he had found in one of the huts.

One of the things that worried Schinz immensely was his beard and hair. Both were beginning to get very long and matty. Finally, when he thought he would go mad if he did not somehow find a way to shave and cut his hair, he stumbled across a pair of rusty scissors. Overcome with joy, he snatched the broken piece of metal, and held it skyward, thanking the Lord. He oiled the scissors and sharpened them on a whetstone. After two hours of happy hacking, he had his beard trimmed and his hair chopped off in a rough, mangy looking crew cut. Just to get rid of the matted mass of filthy hair made his spirits soar.

On the morning of the sixth of June — Schinz’s thirty seventh day on the island — the weather cleared. Once again he was very optimistic. He noted in his dairy before breakfast: “Today is it. I feel it in my bones.” Sure enough, within a few minutes, Schinz heard the sound of aircraft engines. He ran out into the clearing as two F-51 fighters flew over low. He lighted the oil-soaked rags, waved his home-made flags, danced, shrieked, cursed. As the planes flew back and forth overhead, he began to have real hope. He had caught their attention! Then he ran back into the hut and dragged out the dinghy, the Mae West, the G-suit, and placed them in the middle of the clearing, pointing to them.

But soon the aircraft flew away. Worse still, no chopper came. It was the same old story again. What had he done wrong this time? Schinz asked himself. Perhaps it was his clothing. Instead of wearing his flight suit, he had on an old Korean shirt that he had found in one of the huts . Angrily, he wrote in his diary: “They must have mistaken me for a Korean. Can’t I do anything right?” Then he added a postscript: “Get hold of yourself, stupid, don’t crack up.”

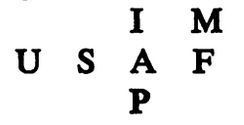

Later that afternoon, Schinz climbed to the highest peak on the island. For three hours he sat staring out at the sea thinking. He could not understand why the Air Force was deliberately ignoring him like this. Certainly the planes had seen the sign, the oil, the Mae West, and other items. What could they be thinking? Obviously, they thought he was just a Korean or perhaps a Communist. What could he do now? He thought of paddling to the mainland in his dinghy. Perhaps he could steal a sampan and sail south to Cho-do. He tossed the idea aside, and began drawing up what he called a “thirty-day plan.” The main feature of the plan was the construction of a new sign. This time he would make it read:

meaning “I am a United States Air Force Pilot.” That ought to convince the Air Rescue people, he thought.

On the way back to camp that afternoon, Schinz came across an old slit trench. As was his custom, he examined it closely for salvageable materials and was surprised to find three trip flares. “Just what I need for my night operations,” he said to himself. He bundled the flares in his arms and hurried back to camp. He set one flare near the fire, pulled the safety catches and fuse. Then he waited for a plane to come over.

A few hours later, Schinz heard the familiar sound of B-26 engines in the distance. He pulled the trip wire, but nothing happened. He looked at the flare and said: “Why in the heck didn’t you go off?” Then he decided to find out. He picked up the flare and fiddled with the trip mechanism. Suddenly it exploded in his face. He was blinded and deafened. Pain numbed his senses. His hands were bloody.

He thought he might stop the bleeding by putting his hands into boiling water so he blindly ran to the water can and put it on the fire to boil. Then he thrust his hands into the hot water. He could not feel a thing; his hands were numb. As he sat holding his hands in the water, his eyesight returned. Slowly Schinz screwed up his courage, then withdrew his hands from the water to see how many fingers he had left. He was surprised to see that they were all there. But he could see that his hands had been peppered by scores of shrapnel pieces. He still hadn’t regained his hearing, so he stuck his fingers in his ears to check for blood; he found none. Within a few minutes he heard a bird singing; he knew he was not permanently deaf. He staggered to his bed and collapsed.

Upon awakening, Schinz saw that each shrapnel hole in his hand had turned into a small pocket of pus. Nervously, he searched for a red line of blood poisoning creeping up his arm. It was not there yet. After breakfast, he boiled more water and applied steaming hot rags to his hands. Then he got all of his needles together and, after carefully sterilizing them, dug into the pus pockets, extracting the shrapnel. It was tedious work, but Schinz knew that he could not survive with infected hands. It would have to be a perfect job. After three hours, he was satisfied.

That night he half-buried the other flares at a distance from the fire, and strung the trip wire into the hut, and tied it to the mosquito net bar. If a plane came over, he could trip the flare from his bed, with no danger of another explosion. Before going to bed, he examined his hands carefully, and though they were beginning to blister in a few places, he concluded that he had stopped the infection. The fact that he had the flares set raised his morale considerably, because heretofore his night operations had been slipshod and ineffective. It was likely that a plane would come over that night.

It was 2:30 A.M. when he awoke. A bright light shone in his eyes. For a minute, he thought he was having a nightmare. He blinked, then stiffened in terror as he saw rifle barrels aimed at him. Hands grabbed him and turned him over. Then he heard voices behind the light.

They were Koreans.

Schinz tried to speak, but no sound came from his throat. He turned over on his face and stuck his blistered hands up, waiting for the wham of the rifle and the impact of the bullet. He prayed quickly. Another hand grabbed his GI shirt collar, then moved to the silver eagles. A voice said in English: “American. American Colonel.” On hearing the English, Schinz shouted: “I surrender, I surrender.” But the Korean put his arm around Schinz, pounded him on the back, and shouted, “O.K., O.K., O.K., O.K.,” over and over again. “We are friends. We help.”

After Schinz had embraced each one of the natives in his delirious joy, he discovered how close he had actually been to death. The men were South Korean soldiers whose job it was to keep islands like Schinz’s “safe” — free from Communist soldiers, so that fighter pilots could bail out and be rescued from them. On a routine sea patrol, the Koreans had spotted the fire as they sailed by. Believing Schinz to be part of a Communist unit that had recently occupied the island, they had come to kill him.

The friendly South Koreans immediately began plans for evacuating Schinz from the island. They promised to take him to Cho-do. Within minutes, one of the Koreans set up a powerful two-way radio and called one Lieutenant “M,” who Schinz later learned was the boss of the group, on another island. Lieutenant “M” and his assistant, Sergeant “D,” owned a powerboat. When they learned of Schinz’s plight, they promised to get under way at once for Schinz-do and pick him up. Six hours later — at 9:00 A.M. — they arrived.

It was risky business putting around in a slow sampan so close to the mouth of the Yalu River. The group boarded the craft and got under way immediately. As the boat chugged steadily southward through the Yellow Sea toward Cho-do, Schinz sat in the bow wolfing down Army rations that the Koreans had given him, occasionally exchanging a word with his rescuers. At a half hour before midnight that night, the boat pulled into Cho-do. Schinz went ashore after first gratefully thanking the Koreans and making sure they had proper papers with which to receive a reward. He watched as the boat turned and headed back in the direction from which it had just come.

Before going to sleep that night in a clean bed with sheets, Schinz shaved, bathed, weighed (he had lost forty pounds), and had a long chat with the men of Air Rescue. There were a lot of unanswered questions: Had they not seen his distress signals? The fires? The flares? What about the aircraft that had flown over time after time, didn’t they report his presence? Had he been deliberately left to starve to death on this lonely island? Why hadn’t they searched for him in the beginning?

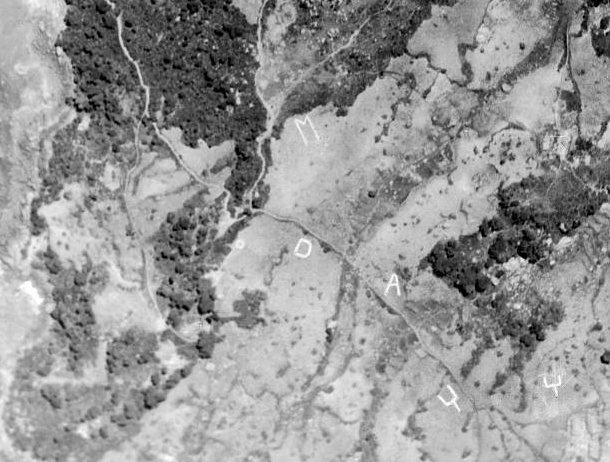

In these conversations, plus later talks with men at his home base, Schinz learned that elaborate search procedures had been initiated after it was found that he was missing. The jets in his own flight had returned to base, refueled, then, joined by scores of other aircraft, had spent the remainder of the day sweeping back and forth over North Korea and MiG Alley looking for his aircraft, or some sign of it. The following morning and the day after, more search planes combed the area, as well as the escape route that Schinz had suggested for disabled aircraft. It was then that Schinz discovered that he had not yo-yoed out of MiG Alley along the escape route as he believed, but had veered west considerably. Thus, the area in which he crashed was not carefully searched.

The Air Rescue people had been watching his activity on the island with some interest for a matter of weeks. However, since no downed airmen were believed to be in the vicinity and since Communist agents were known to be inhabiting most of the islands, Air Rescue believed the activity to be that of a Communist, intent on luring innocent Air Rescue personnel into a trap. For months, the Communists had been attempting to capture a helicopter in this fashion. It was feared that a captured Air Rescue pilot might be persuaded by diabolical Communist techniques to reveal considerable valuable information about the underground and the safe islands, the backbone of the Rescue Service.

For these reasons, Air Rescue and the Joint Operations Center had been reluctant to send a helicopter or seaplane into the area. However, when the distress signals persisted, and after the mayday sign was clearly discerned in aerial photographs, Air Rescue formed a commando party and dispatched them by boat with orders to investigate the island firsthand. When Schinz arrived at Cho-do, he learned that the party had already departed for Schinz-do the day before. Had he not been picked up by the South Korean soldiers, Air Rescue would have evacuated him the following day.

When Schinz arrived at his home base, all hands turned out to greet him. Gabby came, chomping on a big cigar, slapping the gaunt survivor on the back. Colonel Al Kelly was there, anxious to find out what had happened in the critical moment of the dogfight when the two planes became separated. Colonel Joe Mason, Schinz’s friend and boss of the Joint Operations Center, was there to explain the elaborate search that had been carried out. The chaplain came along, too, and as soon as he could, Schinz disappeared with him for more than an hour.

That night, the 51st Fighter-Interceptor staged a memorable party in the officers’ club to celebrate Schinz’s return. Beer and whisky flowed freely. Pilot after pilot came up to Schinz to ask what happened. Little by little, he told bits of the story. Finally, he decided to tell everyone the whole tale at once. He climbed up on the bar and waved his hands. Silence fell over the smoke-filled room. Schinz said, “Now I’m going to tell you all what happened….”

For an hour and a half Schinz stood erect on the bar, talking. There was hardly a sound from the 150 officers , just an occasional cough or the scrape of a chair. Finally, Schinz came to the end of the tale of Schinz-do, and he shook his finger at the men and said, with some feeling, “Men, there is one thing that saved me, and that was God. When that dinghy started drifting out to sea, I prayed that He would bring me back to land. He did. When my lighter was full of sea water, I prayed that it would light, and He made it light.

“Then I got so weak I couldn’t stand up, and I prayed that I would find something to eat, and I did. I found twenty-five bags of rice. When that flare blew up in my face, I prayed that my hands wouldn’t get infected, and they didn’t. When my hair got so I couldn’t stand it, I asked the Lord to help me, and right after that, I found a pair of scissors!