Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Triggernometry: A Gallery of Gunfighters, by Eugene Cunningham (published 1934).

In the period now beginning, Ben drank more heavily than ever. He became a common nuisance to both his friends and his enemies; particularly perhaps, to his friends. Even his most indulgent apologist, the aforesaid Buck Walton, must admit that, when drinking, Ben became overbearing to a degree that made his company highly disagreeable.

His escapades were legion, but all had the similar factor of being irritating. Once, he swaggered into a saloon and, under the influence of continued drinks, conceived the brilliant idea of having the bartenders serve all negro customers at that end of the bar reserved for whites. He brandished a pistol and threatened the saloon’s owner.

Only the coming-between of soberer, cooler heads, prevented bloodshed. The saloon keeper refused point blank to have negroes among the whites and Ben swore that his command would be obeyed. Not even Ben’s warmest — and blindest — partisans could defend this outburst. Not in a southern state where Reconstruction’s savage scenes had been so recently ended! Not in the Texas of today, for that matter. Take a negro out of the “Jim Crow” section and try to put him among the whites and the only question will be how large the riot!

On another occasion, he loaded his pistol with blank cartridges and descended on a variety theatre which, he later explained with some humor, had been drawing trade away from his gambling rooms. He fired the blanks into the crowd with a wild yell and confessed to huge enjoyment at seeing the frightened people fairly wreck the place in their frantic efforts to escape.

This evokes a picture superficially funny. Almost funny, when it is examined. But as a Texas man, growing up in an era when “packing a gun” was the common thing, and as one who has worn belt-hardware a good deal, I fail to see the genuine humor of the situation. Some veteran gunmen — vastly better qualified than I to pass judgment from a gun-handler’s viewpoint — sneer more bitterly even than I, at silly exhibitions such as this.

How many times have I heard the twin admonitions — “don’t pull your gun unless you’re ready to go the whole hog down to the last teency bristle on his tail!” and “don’t point a gun at nobody you ain’t plumb willin’ to shoot, if that’s necessary!”

It amused Ben to watch that panic-stricken crowd mill and stampede like thunder-frightened cattle. But one may inquire why they should not, most logically, have believed that he was aiming lead-tipped cartridges their way? They saw him standing there in the door; saw the puffs of smoke, the red flashes, come from his pistol-muzzles; heard the bellow of the shots. There was Ben Thompson! The killer! The fellow who had shot a poor dago organ-grinder’s instrument to pieces. The man who got drunk and cowed the police force and thereby sniffed as he pleased at the law, in the capital of the state. The “bad man,” whose actions, when drunk, no body could forecast.

No, it is not even almost funny, to some Texas men.

He broke up a stockmen’s convention banquet in similar fashion. Appearing in a doorway, he knocked over a great castor of condiments. The stockmen looked around. There stood Ben Thompson the Killer in the doorway, pistol in hand. It is plain that his record was lurid, for such as those two-fisted, capable men, accustomed to dangers and the handling of weapons, left the hall without ceremony.

Incidentally, here was manifestation of a phenomenon more than once commented in my hearing — the submissiveness in the face of firearms of men themselves used to firearms. Familiarity, with such, does not breed contempt! On the contrary, they know so well the power of the gun that they do not trifle with one.

Raymond Spears, some time ago, had a most verisimilitudinous yarn in Adventure Magazine, about the ease with which some robbers stuck up a crowd of gun experts sitting in the back-end of a sporting goods store. I know that many an outland, outdoors man, reading that tale, nodded his head in complete agreement. The easiest gang in the world to hold up. For they knew, each of them, just what were the chances, the odds, against their making unpunctured resistance. Be that as it may, there is no denying that Ben Thompson stampeded the stockmen’s convention.

Another time he raided the office of the Austin Statesman. Fortunately, neither of his intended victims, the owner or the editor, was present, so bloodshed was avoided. Six charges were brought against Ben for this raid, but only two were ever tried.

The Thompson Luck… The question was, how long now could it continue? His best friends dodged him on the street, for a half-hour in Ben Thompson’s company was sure to mean entanglement in at least a violent misdemeanor. The police (and many of them were ex-soldiers) had a holy horror of coming into conflict with Ben Thompson. Perhaps they could hardly be blamed for their lack of eagerness to enter into a contest with so skilful and merciless a killer. Even Buck Walton admits that the staccato bellow of Ben’s pistol was almost a nightly sound on Austin streets. Men coming out of their houses in the morning, first asked acquaintances they met:

“What did Ben Thompson do, last night?”

For everyone anticipated a grave brawl or a blazing tragedy.

On a March day in 1884, Ben met in Austin an old acquaintance and sometime enemy, King Fisher, who was a figure of scarcely less note in the ranks of gunmen than Thompson himself. King Fisher’s life had been spent on the border; a daring life, a reckless, a defiant; for some years actually criminal. So much so that a whole company of Rangers had been busy breaking up “The King Fisher Gang.”

At this time, however, he was a deputy sheriff of Uvalde County. These kindred spirits wandered about Austin together that day and finally King Fisher suggested that Ben go to San Antonio with him.

Ben, it is said, was up to his usual tricks on board the train. Finally King Fisher had to threaten to kill him to prevent Ben from beating a negro porter and a German passenger.

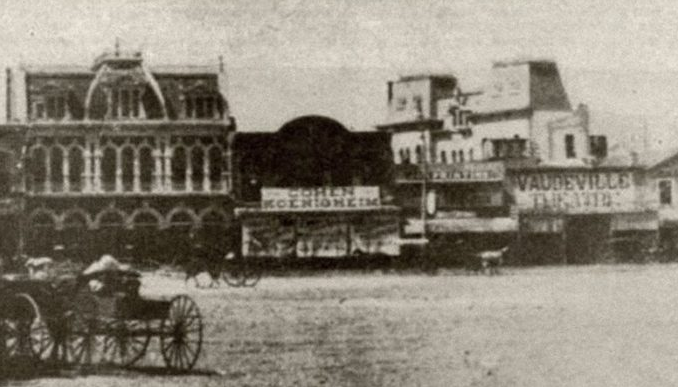

The pair got to San Antonio around eight o’clock in the evening. After supper, they attended East Lynne, playing at a local theatre. When the show was over, they went together to the old Harris place — the Vaudeville — on the plaza, where, just twenty months before, Ben had killed Jack Harris. From this moment on there is no accurate charting of the course of events. Perhaps no other gunplay in the history of Texas was witnessed by so many persons, yet has been the subject of so many conflicting accounts.

They went into the Vaudeville together — that much, we know at least, with certainty. We know too, that they stopped on the way and asked some friends to go with them. These men, knowing Joe Foster and Billy Sims to be at the Vaudeville, energetically declined the invitation. They “had a hunch” and stayed away. What the reason was for a visit by Ben to this place, we do not know.

King Fisher was very fond of Joe Foster, who had supplied him with meals, and tobacco and other comforts during Fisher’s nine months in a San Antonio jail, some years before. Whatever Thompson may have intended doing, of completing a wiping-out of the Vaudeville owners, it seems hardly reasonable that Fisher, who was always openly contemptuous of Thompson, would have entered into the plan merely because it was the redoubtable Ben Thompson who proposed it. King Fisher’s vices, so far as I have ever been able to learn, did not include ingratitude. He would not have been even a passive performer in a blow which included Joe Foster.

In the barroom, Thompson asked that Billy Sims be sent to him. Sims was administrator of the Harris estate. He and Foster were now operating the Vaudeville. It casts some little light on a situation sufficiently murky, to remember that Sims was not precisely a weakling. When somewhat later, he was operating the famous White Elephant Saloon in San Antonio, a certain well-known West Texan gambled there.

He was quite a gunman himself, this West Texan. He had notches for around a half-dozen men. Some there were who quite openly called him “hard case.” He gambled frequently in the Coney Island at El Paso and was in the habit of writing checks to cover his gambling losses. Usually, afterward, he would stop payment on the checks on the pretense that he had been drunk and irresponsible when making them.

But when he wrote his first check in Billy Sims’ White Elephant, Sims came quietly to him and without any show of being impressed by the West Texan’s notched six-shooter:

“Reliable parties,” he said, “tell me that you have a way of writing checks — like this one — and reneging on them. Now, I’m going to cash this check — and collect on it tomorrow!”

They do say — with broad grins — that Billy collected on every check thus given. Without any trouble whatsoever.

This, then, was the man who came into the barroom to Ben Thompson and King Fisher. A man with a good deal of iron in his backbone and one whose hatred of Thompson, born of that deal in Austin when Thompson had run him out of town, had been increased by the killing of his friend, Jack Harris. Somewhat nervously, Sims made the two men welcome.

Nothing is clear, thereafter. But, averaging the testimony given at the coroner’s inquest, one gets a sort of picture — the more accurate, perhaps, if one reflects upon the hair-trigger atmosphere that must have gripped the Vaudeville with appearance of Ben Thompson and the noted King Fisher.

Thompson bought tickets for the variety performance. He and Fisher went upstairs where, in the balcony, spectators might sit comfortably and watch the tawdry performance while being served with drinks.

There were Thompson and Fisher, Billy Sims and a big Mexican policeman, Coy, together. They talked — according to Coy — about the killing of Jack Harris. By the same testimony, King Fisher said that he had come to be amused. Killings, as a topic of conversation, were entirely too commonplace to entertain him. He suggested adjournment to the bar. The party rose; started down stairs. But Thompson, looking about, chanced to see Joe Foster. He called to the spectacled little gambler to have a drink with him.

Foster refused; refused, also, to shake hands with the man who had killed his friend Jack Harris. He wanted no trouble with Thompson, he said. He wanted only to be let alone by him.

Coy and Sims testified to practically the same effect, concerning the subsequent events. Thompson was furious at Joe Foster. He whipped out a pistol and Sims says rammed it into Foster’s mouth. Coy says that he slapped Foster with left hand and drew his pistol with his right hand. Coy was onto him like a terrier. He snatched at the pistol, holding the cylinder as best he could. He says a bullet went by his ear. King Fisher and Thompson both were yelling to Coy to turn loose of the pistol.

Coy, Thompson and Fisher fell in a heap, Thompson’s pistol roaring all the time. Coy did not admit having shot anybody; Sims testified that “the shooting then began on both sides.” All we know is that when the smoke went lifting to canopy the ceiling, Ben Thompson and King Fisher lay together on the floor, dead; that Constable Casanovas had helped Joe Foster downstairs with a bullet through his leg (a wound that killed him shortly); and that Coy turned over to Marshal Shardein a pistol which he said was Ben Thompson’s. It was a six shooter and — contrary to the usual practice of gunmen then and now — had been fully loaded. Five shots had been fired and one loaded cartridge remained.

A coroner’s inquest found that Coy and Foster had killed the two and that it was a justifiable act done to save their own lives. But the old-timers call it an ambush. Captain Jim Gillett heard it talked about at the time. Everyone believed, he tells me, that Thompson was the pitcher that went too often to the well. Austin papers raged indignantly. An autopsy performed in the capital city showed that eight shots had struck Thompson, five of these entering his head in such manner as to prove that they had been fired from above him — which does seem to bear out the old-timers’ story about a bunch of men armed with rifles and shotguns being posted in boxes above Thompson and Fisher.

Much was made of the fact that the coroner’s jury had found only three bullets that had struck Thompson. It was said that the jury’s verdict was made in fear of Sims and his potent crowd.

However, as one who remembers keenly the rivalry that often exists between two adjacent cities, not only in Texas, the attitude of the Austin papers toward the killing of Ben Thompson takes on a sort of patriotic color. As has been pointed out it was well known that Thompson’s race was almost run; it was merely a question of who would kill him, of how many he might kill before he died, and of when the actual event would occur.

He was a nuisance in the capital city; he was more than a nuisance! He was as much a menace as a mad dog. But the tone of the Austin papers of that day might lead an uninformed stranger to believe that the Sacred Cow of the capital had been purely and wantonly slaughtered. But — whatever Austin newspapers said — so died Ben Thompson, March 11, 1884, in the forty-first year of his life.

Even more than John Wesley Hardin or Bill Longley, Ben Thompson seems to have been a very typical product of his times. He had the good traits that men demanded in their friends — courage and loyalty and good humor (when sober). But he outlived the time when his habits could be tolerated. The frontier has ever bred the individualist. There he thrives; for there is room to let him follow (pretty much) his impulses; there, also, is the state of mind that tolerates independence.

Texas, toward ’84, was growing too “civilized” to bear with the individualist as the open range, the frontier, had done. Too civilized to endure being shot up and run by gunmen (and Thompson takes rank — as gunman – second to none that Texas has ever known).

It is indeed a marvel that he could die there in the Vaudeville Variety Theatre without a ring around him of dead men who had gone first. A greater marvel, when one considers the caliber of that dark, lean, swaggering, Uvalde County deputy sheriff, King Fisher, who in the wild, border country along the Rio Grande had a name for desperate gunplay, greater even than Thompson’s own.

Ben Thompson was buried on March 13, 1884, in the city of Austin. The funeral attracted “a vast concourse of people,” says the Daily Dispatch of that day, to witness the burial of a victim of assassination, according to the same authority. One fears there is little reason for doubting the truth of this. But it would have been sheer luck if Thompson had died with boots off. Gunmen of his caliber rarely died “sock-footed.”