Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Literary and General Lectures and Essays, by Charles Kingsley (published 1898).

Let us think for a while upon what the Stage was once, in a republic of the past—what it may be again, I sometimes dream, in some republic of the future. In order to do this, let me take you back in fancy some 2,314 years—440 years before the Christian era, and try to sketch for you—alas! how clumsily—a great, though tiny people, in one of their greatest moments—in one of the greatest moments, it may be, of the human race. For surely it is a great and a rare moment for humanity, when all that is loftiest in it—when reverence for the Unseen powers, reverence for the heroic dead, reverence for the fatherland, and that reverence, too, for self, which is expressed in stateliness and self-restraint, in grace and courtesy; when all these, I say, can lend themselves, even for a day, to the richest enjoyment of life—to the enjoyment of beauty in form and sound, and of relaxation, not brutalising, but ennobling.

Rare, alas! have such seasons been in the history of poor humanity. But when they have come, they have lifted it up one stage higher thenceforth. Men, having been such once, may become such again; and the work which such times have left behind them becomes immortal.

A thing of beauty is a joy for ever.

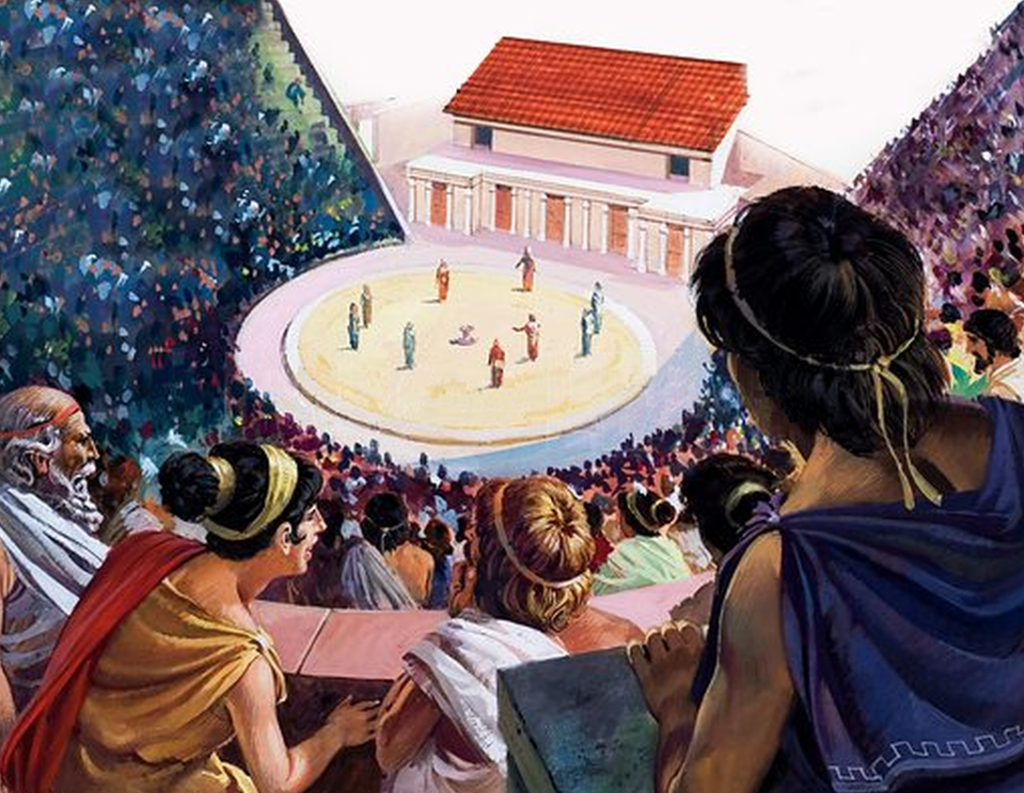

Let me take you to the then still unfurnished theatre of Athens, hewn out of the limestone rock on the south-east slope of the Acropolis.

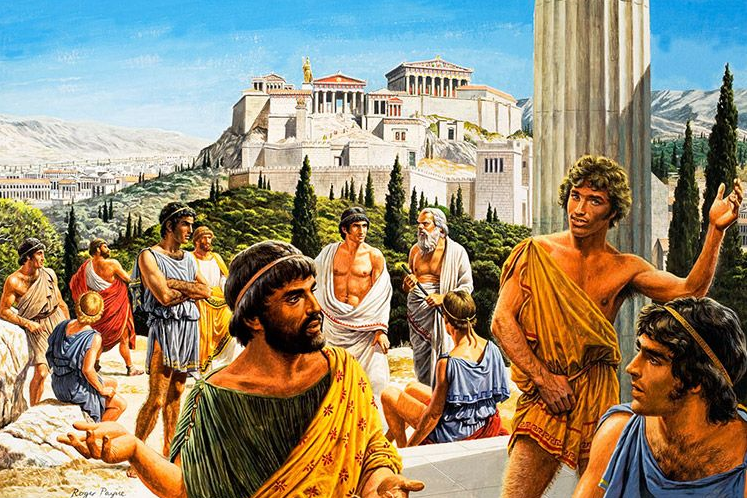

Above are the new marble buildings of the Parthenon, rich with the statues and bas-reliefs of Phidias and his scholars, gleaming white against the blue sky, with the huge bronze statue of Athené Promachos, fifty feet in height, towering up among the temples and colonnades. In front, and far below, gleams the blue sea, and Salamis beyond.

And there are gathered the people of Athens—fifty thousand of them, possibly, when the theatre was complete and full. If it be fine, they all wear garlands on their heads. If the sun be too hot, they wear wide-brimmed straw hats. And if a storm comes on, they will take refuge in the porticoes beneath; not without wine and cakes, for what they have come to see will last for many an hour, and they intend to feast their eyes and ears from sunrise to sunset. On the highest seats are slaves and freedmen, below them the free citizens; and on the lowest seats of all are the dignitaries of the republic—the priests, the magistrates, and the other καλοι καyαθι—the fair and good men—as the citizens of the highest rank were called, and with them foreign ambassadors and distinguished strangers. What an audience! the rapidest, subtlest, wittiest, down to the very cobblers and tinkers, the world has ever seen. And what noble figures on those front seats; Pericles, with Aspasia beside him, and all his friends—Anaxagoras the sage, Phidias the sculptor, and many another immortal artist; and somewhere among the free citizens, perhaps beside his father Sophroniscus the sculptor, a short, square, pug-nosed boy of ten years old, looking at it all with strange eyes—“who will be one day,” so said the Pythoness at Delphi, “the wisest man in Greece”—sage, metaphysician, humorist, warrior, patriot, martyr—for his name is Socrates.

All are in their dresses of office; for this is not merely a day of amusement, but of religions ceremony; sacred to Dionysos—Bacchus, the inspiring god, who raises men above themselves, for good—or for evil.

The evil, or at least the mere animal aspect of that inspiration, was to be seen in forms grotesque and sensuous enough in those very festivals, when the gayer and coarser part of the population, in town and country, broke out into frantic masquerade—of which the silly carnival of Rome is perhaps the last paltry and unmeaning relic—“when,” as the learned O. Müller says, “the desire of escaping from self into something new and strange, of living in an imaginary world, broke forth in a thousand ways; not merely in revelry and solemn though fantastic songs, but in a hundred disguises, imitating the subordinate beings—satyrs, pans, and nymphs, by whom the god was surrounded, and through whom life seemed to pass from him into vegetation, and branch off into a variety of beautiful or grotesque forms—beings who were ever present to the fancy of the Greeks, as a convenient step by which they could approach more nearly to the presence of the Divinity.” But even out of that seemingly bare chaos, Athenian genius was learning how to construct, under Eupolis, Cratinus, and Aristophanes, that elder school of comedy, which remains not only unsurpassed, but unapproachable, save by Rabelais alone, as the ideal cloudland of masquerading wisdom, in which the whole universe goes mad—but with a subtle method in its madness.

Yes, so it has been, under some form or other, in every race and clime—ever since Eve ate of the magic fruit, that she might be as a god, knowing good and evil, and found, poor thing, as most have since, that it was far easier and more pleasant to know the evil than to know the good. But that theatre was built that men might know therein the good as well as the evil. To learn the evil, indeed, according to their light, and the sure vengeance of Até and the Furies which tracks up the evil-doer. But to learn also the good—lessons of piety, patriotism, heroism, justice, mercy, self-sacrifice, and all that comes out of the hearts of men and women not dragged below, but raised above themselves; and behind all—at least in the nobler and earlier tragedies of Æschylus and Sophocles, before Euripides had introduced the tragedy of mere human passion; that sensation tragedy, which is the only one the world knows now, and of which the world is growing rapidly tired—behind all, I say, lessons of the awful and unfathomable mystery of human existence—of unseen destiny; of that seemingly capricious distribution of weal and woe, to which we can find no solution on this side the grave, for which the old Greek could find no solution whatsoever.

Therefore there was a central object in the old Greek theatre, most important to it, but which did not exist in the old Roman, and does not exist in our theatres, because our tragedies, like the Roman, are mere plays concerning love, murder, and so forth, while the Greek were concerning the deepest relations of man to the Unseen.

The almost circular orchestra, or pit, between the benches and the stage, was empty of what we call spectators—because it was destined for the true and ideal spectators—the representatives of humanity; in its centre was a round platform, the θυμελη—originally the altar of Bacchus—from which the leader of these representatives, the leader of the Chorus, could converse with the actors on the stage and take his part in the drama; and round this thymelé the Chorus ranged with measured dance and song, chanting, to the sound of a simple flute, odes such as the world had never heard before or since, save perhaps in the temple-worship at Jerusalem. A chorus now, as you know, merely any number of persons singing in full harmony on any subject. The Chorus was then in tragedy, and indeed in the higher comedy, what Schlegel well calls “the ideal spectator”—a personified reflection on the action going on, the incorporation into the representation itself of the sentiments of the poet, as the spokesman of the whole human race. He goes on to say (and I think truly), “that the Chorus always retained among the Greeks a peculiar national signification, publicity being, according to their republican notions, essential to the completeness of every important transaction.” Thus the Chorus represented idealised public opinion; not, of course, the shifting hasty public opinion of the moment—to that it was a conservative check, and it calmed it to soberness and charity—for it was the matured public opinion of centuries; the experience, and usually the sad experience, of many generations; the very spirit of the Greek race.

The Chorus might be composed of what the poet would. Of ancient citizens, waiting for their sons to come back from the war, as in the “Agamemnon” of Æschylus; of sea-nymphs, as in his “Prometheus Bound;” even of the very Furies who hunt the matricide, as in his “Eumenides;” of senators, as in the “Antigone” of Sophocles; or of village farmers, as in his “Œdipus at Colonos”—and now I have named five of the greatest poems, as I hold, written by mortal man till Dante rose. Or it may be the Chorus was composed—as in the comedies of Aristophanes, the greatest humorist the world has ever seen—of birds, or of frogs, or even of clouds. It may rise to the level of Don Quixote, or sink to that of Sancho Panza; for it is always the incarnation of such wisdom, heavenly or earthly, as the poet wishes the people to bring to bear on the subject-matter.

But let the poets themselves, rather than me, speak awhile. Allow me to give you a few specimens of these choruses—the first as an example of that practical and yet surely not un-divine wisdom, by which they supplied the place of our modern preacher, or essayist, or didactic poet.

Listen to this of the old men’s chorus in the “Agamemnon,” in the spirited translation of my friend Professor Blackie:

’Twas said of old, and ’tis said to-day,

That wealth to prosperous stature grown

Begets a birth of its own:

That a surfeit of evil by good is prepared,

And sons must bear what allotment of woe

Their sires were spared.

But this I refuse to believe: I know

That impious deeds conspire

To beget an offspring of impious deeds

Too like their ugly sire.

But whoso is just, though his wealth like a river

Flow down, shall be scathless: his house shall rejoice

In an offspring of beauty for ever.

The heart of the haughty delights to beget

A haughty heart. From time to time

In children’s children recurrent appears

The ancestral crime.

When the dark hour comes that the gods have decreed

And the Fury burns with wrathful fires,

A demon unholy, with ire unabated,

Lies like black night on the halls of the fated;

And the recreant Son plunges guiltily on

To perfect the guilt of his Sires.

But Justice shines in a lowly cell;

In the homes of poverty, smoke-begrimed,

With the sober-minded she loves to dwell.

But she turns aside

From the rich man’s house with averted eye,

The golden-fretted halls of pride

Where hands with lucre are foul, and the praise

Of counterfeit goodness smoothly sways;

And wisely she guides in the strong man’s despite

All things to an issue of RIGHT.

Let me now give you another passage from the “Eumenides”—or “Furies”—of Æschylus.

Orestes, Prince of Argos, you must remember, has avenged on his mother Clytemnestra the murder of his father, King Agamemnon, on his return from Troy. Pursued by the Furies, he takes refuge in the temple of Apollo at Delphi, and then, still Fury-haunted, goes to Athens, where Pallas Athené, the warrior-maiden, the tutelary goddess of Athens, bids him refer his cause to the Areopagus, the highest court of Athens, Apollo acting as his advocate, and she sitting as umpire in the midst. The white and black balls are thrown into the urn, and are equal; and Orestes is only delivered by the decision of Athené—as the representative of the nearer race of gods, the Olympians, the friends of man, in whose likeness man is made. The Furies are the representatives of the older and darker creed—which yet has a depth of truth in it—of the irreversible dooms which underlie all nature; and which represent the Law, and not the Gospel, the consequence of the mere act, independent of the spirit which has prompted it.

They break out in fury against the overbearing arrogance of these younger gods. Athené bears their rage with equanimity, addresses them in the language of kindness, even of veneration, till these so indomitable beings are unable to withstand the charm of her mild eloquence. They are to have a sanctuary in the Athenian land, and to be called no more Furies (Erinnys), but Eumenides—the well-conditioned—the kindly goddesses. And all ends with a solemn precession round the orchestra, with hymns of blessing, while the terrible Chorus of the Furies, clothed in black, with blood-stained girdles, and serpents in their hair, in masks having perhaps somewhat of the terrific beauty of Medusa-masks, are convoyed to their new sanctuary by a procession of children, women, and old men in purple robes with torches in their hands, after Athené and the Furies have sung, in response to each other, a chorus from which I must beg leave to give you an extract or two:

Eldest Fury (Leader of the Chorus).

Far from thy dwelling, and far from thy border,

By the grace of my godhead benignant I order

The blight which may blacken the bloom of the trees.

Far from thy border, and far from thy dwelling,

Be the hot blast which shrivels the bud in its swelling,

The seed-rotting taint, and the creeping disease.

Thy flocks be still doubled, thy seasons be steady,

And when Hermes is near thee, thy hand be still ready

The Heaven-dropt bounty to seize.

Athené.

Hear her words, my city’s warders—

Fraught with blessings, she prevaileth

With Olympians and Infernals,

Dread Erinnys much revered.

Mortal faith she guideth plainly

To what goal she pleaseth, sending

Songs to some, to others days

With tearful sorrows dulled.

Furies.

Far from thy border

The lawless disorder

That sateless of evil shall reign;

Far from thy dwelling,

The dear blood welling,

That taints thine own hearth with the slain.

When slaughter from slaughter

Shall flow like the water,

And rancour from rancour shall grow

But joy with joy blending,

Live, each to all lending;

And hating one-hearted the foe.

When bliss hath departed;

From love single-hearted,

A fountain of healing shall flow.

Athené.

Wisely now the tongue of kindness

Thou hast found, the way of love.

And these terror-speaking faces

Now look wealth to me and mine.

Her so willing, ye more willing,

Now receive. This land and city,

On ancient right securely throned,

Shall shine for evermore.

Furies.

Hail, and all hail, mighty people, be greeted,

On the sons of Athena shines sunshine the clearest.

Blest people, near Jove the Olympian seated.

And dear to the maiden his daughter the dearest.

Timely wise ’neath the wings of the daughter ye gather,

And mildly looks down on her children the Father.

Those of you here who love your country as well as the old Athenians loved theirs, will feel at once the grand political significance of such a scene, in which patriotism and religion become one—and feel, too, the exquisite dramatic effect of the innocent, the weak, the unwarlike, welcoming among them, without fear, because without guilt, those ancient snaky-haired sisters, emblems of all that is most terrible and most inscrutable, in the destiny of nations, of families, and of men:

To their hallowed habitations

’Neath Ogygian earth’s foundations

In that darksome hall

Sacrifice and supplication

Shall not fail. In adoration

Silent worship all.

Listen again, to the gentler patriotism of a gentler poet, Sophocles himself. The village of Colonos, a mile from Athens, was his birthplace; and in his “Œdipus Coloneus,” he makes his Chorus of village officials sing thus of their consecrated olive grove:

In good hap, stranger, to these rural seats

Thou comest, to this region’s blest retreats,

Where white Colonos lifts his head,

And glories in the bounding steed.

Where sadly sweet the frequent nightingale

Impassioned pours his evening song,

And charms with varied notes each verdant vale,

The ivy’s dark-green boughs among,

Or sheltered ’neath the clustering vine

Which, high above him forms a bower,

Safe from the sun or stormy shower,

Where frolic Bacchus often roves,

And visits with his fostering nymphs the groves,

Bathed in the dew of heaven each morn,

Fresh is the fair Narcissus born,

Of those great gods the crown of old;

The crocus glitters, robed in gold.

Here restless fountains ever murmuring glide,

And as their crispèd streamlets play,

To feed, Cephisus, thine unfailing tide,

Fresh verdure marks their winding way.

Here oft to raise the tuneful song

The virgin band of Muses deigns,

And car-borne Aphrodite guides her golden reins.

Then they go on, this band of village elders, to praise the gods for their special gifts to that small Athenian land. They praise Pallas Athené, who gave their forefathers the olive; then Poseidon—Neptune, as the Romans call him—who gave their forefathers the horse; and something more—the ship—the horse of the sea, as they, like the old Norse Vikings after them, delighted to call it

Our highest vaunt is this—Thy grace,

Poseidon, we behold,

The ruling curb, embossed with gold,

Controls the courser’s managed pace,

Though loud, oh king, thy billows roar,

Our strong hands grasp the labouring oar,

And while the Nereids round it play,

Light cuts our bounding bark its way.

What a combination of fine humanities! Dance and song, patriotism and religion, so often parted among us, have flowed together into one in these stately villagers; each a small farmer; each a trained soldier, and probably a trained seaman also; each a self-governed citizen; and each a cultured gentleman, if ever there were gentlemen on earth.

But what drama, doing, or action—for such is the meaning of the word—is going on upon the stage, to be commented on by the sympathising Chorus?

One drama, at least, was acted in Athens in that year—440 B.C.—which you, I doubt not, know well—“Antigone,” that of Sophocles, which Mendelssohn has resuscitated in our own generation, by setting it to music, divine indeed, though very different from the music to which it was set, probably by Sophocles himself, at its first, and for aught we know, its only representation; for pieces had not then, as now, a run of a hundred nights and more. The Athenian genius was so fertile, and the Athenian audience so eager for novelty, that new pieces were demanded, and were forthcoming, for each of the great festivals, and if a piece was represented a second time it was usually after an interval of some years. They did not, moreover, like the moderns, run every night to some theatre or other, as a part of the day’s amusement. Tragedy, and even comedy, were serious subjects, calling out, not a passing sigh, or passing laugh, but all the higher faculties and emotions. And as serious subjects were to be expressed in verse and music, which gave stateliness, doubtless, even to the richest burlesques of Aristophanes, and lifted them out of mere street-buffoonery into an ideal fairyland of the grotesque, how much more stateliness must verse and music have added to their tragedy! And how much have we lost, toward a true appreciation of their dramatic art, by losing almost utterly not only the laws of their melody and harmony, but even the true metric time of their odes!—music and metre, which must have surely been as noble as their poetry, their sculpture, their architecture, possessed by the same exquisite sense of form and of proportion. One thing we can understand—how this musical form of the drama, which still remains to us in lower shapes, in the oratorio, in the opera, must have helped to raise their tragedies into that ideal sphere in which they all, like the “Antigone,” live and move. So ideal and yet so human; nay rather, truly ideal, because truly human. The gods, the heroes, the kings, the princesses of Greek tragedy were dear to the hearts of Greek republicans, not merely as the founders of their states, not merely as the tutelary deities, many of them, of their country: but as men and women like themselves, only more vast; with mightier wills, mightier virtues, mightier sorrows, and often mightier crimes; their inward free-will battling, as Schlegel has well seen, against outward circumstance and overruling fate, as every man should battle, unless he sink to be a brute. “In tragedy,” says Schlegel—uttering thus a deep and momentous truth—“the gods themselves either come forward as the servants of destiny and mediate executors of its decrees, or approve themselves godlike only by asserting their liberty of action and entering upon the same struggles with fate which man himself has to encounter.” And I believe this, that this Greek tragedy, with its godlike men and manlike gods, and heroes who had become gods by the very vastness of their humanity, was a preparation, and it may be a necessary preparation, for the true Christian faith in a Son of Man, who is at once utterly human and utterly divine. That man is made in the likeness of God—is the root idea, only half-conscious, only half-expressed, but instinctive, without which neither the Greek Tragedies nor the Homeric Poems, six hundred years before them, could have been composed. Doubtless the idea that man was like a god degenerated too often into the idea that the gods were like men, and as wicked. But that travestie of a great truth is not confined to those old Greeks. Some so-called Christian theories—as I hold—have sinned in that direction as deeply as the Athenians of old.

Meanwhile, I say, that this long acquiescence in the conception of godlike struggle, godlike daring, godlike suffering, godlike martyrdom; the very conception which was so foreign to the mythologies of any other race—save that of the Jews, and perhaps of our own Teutonic forefathers—did prepare, must have prepared men to receive as most rational and probable, as the satisfaction of their highest instincts, the idea of a Being in whom all those partial rays culminated in clear, pure light; of a Being at once utterly human and utterly divine; who by struggle, suffering, self-sacrifice, without a parallel, achieved a victory over circumstance and all the dark powers which beleaguer main without a parallel likewise.

Take, as an example, the figure which you know best—the figure of Antigone herself—devoting herself to be entombed alive, for the sake of love and duty. Love of a brother, which she can only prove, alas! by burying his corpse. Duty to the dead, an instinct depending on no written law, but springing out of the very depth of those blind and yet sacred monitions which prove that the true man is not an animal, but a spirit; fulfilling her holy purpose, unchecked by fear, unswayed by her sisters’ entreaties. Hardening her heart magnificently till her fate is sealed; and then after proving her godlike courage, proving the tenderness of her womanhood by that melodious wail over her own untimely death and the loss of marriage joys, which some of you must know from the music of Mendelssohn, and which the late Dean Milman has put into English thus:

Come, fellow-citizens, and see

The desolate Antigone.

On the last path her steps shall treed,

Set forth, the journey of the dead,

Watching, with vainly lingering gaze,

Her last, last sun’s expiring rays.

Never to see it, never more,

For down to Acheron’s dread shore,

A living victim am I led

To Hades’ universal bed.

To my dark lot no bridal joys

Belong, nor o’er the jocund noise

Of hymeneal chant shall sound for me,

But death, cold death, my only spouse shall be.

Oh tomb! Oh bridal chamber! Oh deep-delved

And strongly-guarded mansion! I descend

To meet in your dread chambers all my kindred,

Who in dark multitudes have crowded down

Where Proserpine received the dead. But I,

The last—and oh how few more miserable!—

Go down, or ere my sands of life are run.

And let me ask you whether the contemplation of such a self-sacrifice should draw you, should have drawn those who heard the tale nearer to, or farther from, a certain cross which stood on Calvary some 1800 years ago? May not the tale of Antigone heard from mother or from nurse have nerved ere now some martyr-maiden to dare and suffer in an even holier cause?

But to return. This set purpose of the Athenian dramatists of the best school to set before men a magnified humanity, explains much in their dramas which seems to us at first not only strange but faulty. The masks which gave one grand but unvarying type of countenance to each well-known historic personage, and thus excluded the play of feature, animated gesture, and almost all which we now consider as “acting” proper; the thick-soled cothurni which gave the actor a more than human stature; the poverty (according to our notions) of the scenery, which usually represented merely the front of a palace or other public place, and was often though not always unchanged during the whole performance; the total absence, in fact, of anything like that scenic illusion which most managers of theatres seem now to consider as their highest achievement; the small number of the actors, two, or at most three only, being present on the stage at once,—the simplicity of the action, in which intrigue (in the playhouse sense) and any complication of plot are utterly absent; all this must have concentrated not the eye of the spectator on the scene, but his ear upon the voice, and his emotions on the personages who stood out before him without a background, sharp-cut and clear as a group of statuary, which is the same, place it where you will, complete in itself—a world of beauty, independent of all other things and beings save on the ground on which it needs must stand. It was the personage rather than his surroundings, which was to be impressed by every word on the spectator’s heart and intellect; and the very essence of Greek tragedy is expressed in the still famous words of Medea:

Che resta? Io.

Contrast this with the European drama—especially with the highest form of it—our own Elizabethan. It resembles, as has been often said in better words than mine, not statuary but painting. These dramas affect colour, light, and shadow, background whether of town or country, description of scenery where scenic machinery is inadequate, all, in fact, which can blend the action and the actors with the surrounding circumstances, without letting them altogether melt into the circumstances; which can show them a part of the great whole, by harmony or discord with the whole universe, down to the flowers beneath their feet. This, too, had to be done: how it became possible for even the genius of a Shakespeare to get it done, I may with your leave hint to you hereafter. Why it was not given to the Greeks to do it, I know not.

Let us at least thank them for what they did. One work was given them, and that one they fulfilled as it had never been fulfilled before; as it will never need to be fulfilled again; for the Greeks’ work was done not for themselves alone but for all races in all times; and Greek Art is the heirloom of the whole human race; and that work was to assert in drama, lyric, sculpture, music, gymnastic, the dignity of man—the dignity of man which they perceived for the most part with their intense æsthetic sense, through the beautiful in man. Man with them was divine, inasmuch as he could perceive beauty and be beautiful himself. Beauty might be physical, æsthetic, intellectual, moral. But in proportion as a thing was perfect it revealed its own perfection by its beauty. Goodness itself was a form—though the highest form—of beauty. Καλος meant both the physically beautiful and the morally good; αισχρος both the ugly and the bad.

Out of this root-idea sprang the whole of that Greek sculpture, which is still, and perhaps ever will be, one of the unrivalled wonders of the world.

Their first statues, remember, were statues of the gods. This is an historic fact. Before B.C. 580 there were probably no statues in Greece save those of deities. But of what form? We all know that the usual tendency of man has been to represent his gods as more or less monstrous. Their monstrosity may have been meant, as it was certainly with the Mexican idols, and probably those of the Semitic races of Syria and Palestine, to symbolise the ferocious passions which they attributed to those objects of their dread, appeasable alone by human sacrifice. Or the monstrosity, as with the hawk-headed or cat-headed Egyptian idols, the winged bulls of Nineveh and Babylon, the many-handed deities of Hindostan—merely symbolised powers which could not, so the priest and the sculptor held, belong to mere humanity. Now, of such monstrous forms of idols, the records in Greece are very few and very ancient—relics of an older worship, and most probably of an older race. From the earliest historic period, the Greek was discerning more and more that the divine could be best represented by the human; the tendency of his statuary was more and more to honour that divine, by embodying it in the highest human beauty.

In lonely mountain shrines there still might linger, feared and honoured, dolls like those black virgins, of unknown antiquity, which still work wonders on the European continent. In the mysterious cavern of Phigalia, for instance, on the Eleatic shore of Peloponnese, there may have been in remote times—so the legend ran—an old black wooden image, a woman with a horse’s head and mane, and serpents growing round her head, who held a dolphin in one hand and a dove in the other. And this image may have been connected with old nature-myths about the marriage of Demeter and Poseidon—that is, of encroachments of the sea upon the land; and the other myths of Demeter, the earth-mother, may have clustered round the place, till the Phigalians were glad—for it was profitable as well as honourable—to believe that in their cavern Demeter sat mourning for the loss of Proserpine, whom Pluto had carried down to Hades, and all the earth was barren till Zeus sent the Fates, or Iris, to call her forth, and restore fertility to the world. And it may be true—the legend as Pausanias tells it 600 years after—that the old wooden idol having been burnt, and the worship of Demeter neglected till a famine ensued, the Phigalians, warned by the Oracle of Delphi, hired Onatas, a contemporary of Polygnotus and Phidias, to make them a bronze replica of the old idol, from some old copy and from a drama of his own. The story may be true. When Pausanias went thither, in the second century after Christ, the cave and the fountain, and the sacred grove of oaks, and the altar outside, which was to be polluted with the blood of no victim—the only offerings being fruits and honey, and undressed wool—were still there. The statue was gone. Some said it had been destroyed by the fall of the cliff; some were not sure that it had ever been there at all. And meanwhile Praxiteles had already brought to perfection (Paus. 1, 2, sec. 4) the ideal of Demeter, mother-like, as Heré—whom we still call Juno now—but softer-featured, and her eyes more closed.

And so for mother earth, as for the rest, the best representation of the divine was the human. Now, conceive such an idea taking hold, however slowly, of a people of rare physical beauty, of acutest eye for proportion and grace, with opportunities of studying the human figure such as exist nowhere now, save among tropic savages, and gifted, moreover, in that as in all other matters, with that inmate diligence, of which Mr. Carlyle has said, “that genius is only an infinite capacity of taking pains,” and we can understand somewhat of the causes which produced those statues, human and divine, which awe and shame the artificiality and degeneracy of our modern so-called civilisation—we can understand somewhat of the reverence for the human form, of the careful study of every line, the storing up for use each scattered fragment of beauty of which the artist caught sight, even in his daily walks, and consecrating it in his memory to the service of him or her whom he was trying to embody in marble or in bronze. And when the fashion came in of making statues of victors in the games, and other distinguished persons, a new element was introduced, which had large social as well as artistic results. The sculptor carried his usual reverence into his careful delineation of the victor’s form, while he obtained in him a model, usually of the very highest type, for perfecting his idea of some divinity. The possibility of gaining the right to a statue gave a fresh impulse to all competitors in the public games, and through them to the gymnastic training throughout all the states of Greece, which made the Greeks the most physically able and graceful, as well as the most beautiful people known to the history of the human race,—a people who, reverencing beauty, reverenced likewise grace or acted beauty, so utterly and honestly, that nothing was too humble for a free man to do, if it were not done awkwardly and ill. As an instance, Sophocles himself—over and above his poetic genius, one of the most cultivated gentlemen, as well as one of the most exquisite musicians, dancers, and gymnasts, and one of the most just, pious, and gentle of all Greece—could not, by reason of the weakness of his voice, act in his own plays, as poets were wont to do, and had to perform only the office of stage-manager. Twice he took part in the action, once as the blind old Thamyris playing on the harp, and once in his own lost tragedy, the “Nausicaa.” There in the scene in which the Princess, as she does in Homer’s “Odyssey,” comes down to the sea-shore with her maidens to wash the household clothes, and then to play at ball—Sophocles himself, a man then of middle age, did the one thing he could do better than any there—and, dressed in women’s clothes, among the lads who represented the maidens, played at ball before the Athenian people.

Just sixty years after the representation of the “Antigone,” 10,000 Greeks, far on the plains of Babylon, cut through the whole Persian army, as the railway train cuts through a herd of buffalo, and then losing all their generals by treacherous warfare, fought their way north from Babylon to Trebizond on the Black Sea, under the guidance of a young Athenian, a pupil of Socrates, who had never served in the army before. The retreat of Xenophon and his 10,000 will remain for ever as one of the grandest triumphs of civilisation over brute force: but what made it possible? That these men, and their ancestors before them, had been for at least 100 years in training, physical, intellectual, and moral, which made their bodies and their minds able to dare and suffer like those old heroes of whom their tragedy had taught them, and whose spirits they still believed would help the valiant Greek. And yet that feat, which looks to us so splendid, attracted, as far as I am aware, no special admiration at the time. So was the cultivated Greek expected to behave whenever he came in contact with the uncultivated barbarian.

But from what had sprung in that little state, this exuberance of splendid life, physical, æsthetic, intellectual, which made, and will make the name of Athens and of the whole cluster of Greek republics for ever admirable to civilised man? Had it sprung from long years of peaceful prosperity? From infinite making of money and comfort, according to the laws of so-called political economy, and the dictates of enlightened selfishness? Not so. But rather out of terror and agony, and all but utter ruin—and out of a magnificent want of economy, and the divine daring and folly of self-sacrifice.

In Salamis across the strait a trophy stood, and round that trophy, forty years before, Sophocles, the author of “Antigone,” then sixteen years of age, the loveliest and most cultivated lad in Athens, undraped like a faun, with lyre in hand, was leading the Chorus of Athenian youths, and singing to Athené, the tutelary goddess, a hymn of triumph for a glorious victory—the very symbol of Greece and Athens, springing up into a joyous second youth after invasion and desolation, as the grass springs up after the prairie fire has passed. But the fire had been terrible. It had burnt Athens at least, down to the very roots. True, while Sophocles was dancing, Xerxes, the great king of the East, foiled at Salamis, as his father Darius had been foiled at Marathon ten years before, was fleeing back to Persia, leaving his innumerable hosts of slaves and mercenaries to be destroyed piecemeal, by land at Platea, by sea at Mycalé. The bold hope was over, in which the Persian, ever since the days of Cyrus, had indulged—that he, the despot of the East, should be the despot of the West likewise. It seemed to them as possible, though not as easy, to subdue the Aryan Greek, as it had been to subdue the Semite and the Turanian, the Babylonian and the Syrian; to riffle his temples, to destroy his idols, carry off his women and children as colonists into distant lands, as they had been doing with all the nations of the East. And they had succeeded with isolated colonies, isolated islands of Greeks, and the shores of Asia Minor. But when they dared, at last, to attack the Greek in his own sacred land of Hellas, they found they had bearded a lion in his den. Nay rather—as those old Greeks would have said—they had dared to attack Pallas Athené, the eldest daughter of Zeus—emblem of that serene and pure divine wisdom, of whom Solomon sang of old: “The Lord possessed me in the beginning of His way, before His works of old. When He prepared the heavens, I was there, when He appointed the foundation of the earth, then was I by him, as one brought up with Him, and I was daily His delight, rejoicing always before Him: rejoicing in the habitable part of His earth; and my delight was with the sons of men”—to attack Athené and her brother Apollo, Lord of light, and beauty, and culture, and grace, and inspiration—to attack them, not in the name of Ormuzd, nor of any other deity, but in the name of mere brute force and lust of conquest. The old Persian spirit was gone out of them. They were the symbols now of nothing save despotism and self-will, wealth and self-indulgence. They, once the children of Ormuzd or light, had become the children of Ahriman or darkness; and therefore it was, as I believe, that Xerxes’ 1000 ships, and the two million (or, as some have it, five million) human beings availed naught against the little fleets and little battalions of men who believed with a living belief in Athené and Apollo, and therefore—ponder it well, for it is true—with a living belief, under whatsoever confusions and divisions of personality, in a God who loved, taught, inspired men, a just God who befriended the righteous cause, the cause of freedom and patriotism, a Deity, the echo of whose mind and will to man was the song of Athené on Olympus, when she

Chanted of order and right, and of foresight, and order of peoples;

Chanted of labour and craft, wealth in the port and the garner;

Chanted of valour and fame, and the man who can fall with the foremost,

Fighting for children and wife, and the field which his father bequeathed him.

Sweetly and cunningly sang she, and planned new lessons for mortals.

Happy who hearing obey her, the wise unsullied Athené.

Ah, that they had always obeyed her, those old Greeks. But meanwhile, as I said, the agony had been extreme. If Athens had sinned, she had been purged as by fire; and the fire—surely of God—had been terrible. Northern Greece had either been laid waste with fire and sword, or had gone over to the Persian, traitors in their despair. Attica, almost the only loyal state, had been overrun; the old men, women, and children had fled to the neighbouring islands, or to the Peloponnese. Athens itself had been destroyed; and while young Sophocles was dancing round the trophy at Salamis, the Acropolis was still a heap of blackened ruins.

But over and above their valour, over and above their loyalty, over and above their exquisite æsthetic faculty, these Athenians had a resilience of self-reliant energy, like that of the French—like that of the American people after the fire of Chicago; and Athens rose from her ashes to be awhile, not only, as she had nobly earned by suffering and endurance, the leading state in Greece, but a mighty fortress, a rich commercial port, a living centre of art, poetry, philosophy, such as this earth has never seen before or since.

On the plateau of that little crag of the Acropolis some eight hundred feet in length, by four hundred in breadth—about the size and shape of the Castle Rock at Edinburgh—was gathered, within forty years of the battle of Salamis, more and more noble beauty than ever stood together on any other spot of like size.

The sudden relief from crushing pressure, and the joyous consciousness of well-earned honours, made the whole spirit-nature of the people blossom out, as it were, into manifold forms of activity, beauty, research, and raised, in raising Greece, the whole human race thenceforth.

What might they not have done—looking at what they actually did—for the whole race of man?

But no—they fell, even more rapidly than they rose, till their grace and their cultivation, for them they could not lose, made them the willing ministers to the luxury, the frivolity, the sentimentality, the vice of the whole old world—the Scapia or Figaro of the old world—infinitely able, but with all his ability consecrated to the service of his own base self. The Greekling—as Juvenal has it—in want of a dinner, would climb somehow to heaven itself, at the bidding of his Roman master.

Ah what a fall! And what was the inherent weakness which caused that fall?

I say at once—want of honesty. The Greek was not to be depended on; if it suited him, he would lie, betray, overreach, change sides, and think it no sin. He was the sharpest of men. Sharp practice, in our modern sense of the word, was the very element in which he floated. Any scholar knows it. In the grand times of Marathon and Salamis, down to the disastrous times of the Peloponnesian War and the thirty tyrants, no public man’s hands were clean, with the exception, perhaps, of Aristides, who was banished because men were tired of hearing him called the Just. The exciting cause of the Peloponnesian war, and the consequent downfall of Athens, was not merely the tyranny she exercised over the states allied to her, it was the sharp practice of the Athenians, in misappropriating the tribute paid by the allies to the decoration of Athens. And in laying the foundations of the Parthenon was sown, by a just judgment, the seed of ruin for the state which gloried in it. And if the rulers were such, what were the people? If the free were such, what were the slaves?

Hence, weakness at home and abroad, mistrust of generals and admirals, paralysing all bold and clear action, peculations and corruptions at home, internecine wars between factions inside states, and between states or groups of states, revolutions followed by despotism, and final exhaustion and slavery—slavery to a people who were coming across the western sea, hard-headed, hard-hearted, caring nothing for art, or science, whose pleasures were coarse and cruel, but with a certain rough honesty, reverence for country, for law, and for the ties of a family—men of a somewhat old English type, who had over and above, like the English, the inspiring belief that they could conquer the whole world, and who very nearly succeeded in that—as we have, to our great blessing, not succeeded—I mean, of course, the Romans.