Editor’s note: The following is extracted from First and Last, by Hilaire Belloc (published 1911).

I never remember an historian yet, nor a topographer either, who could tell me, or even pretend to explain by a theory, how it was that certain things of the past utterly and entirely disappear.

It is a commonplace that everything is subject to decay, and a commonplace which the false philosophy of our time is too apt to forget. Did we remember that commonplace we should be a little more humble in our guesswork, especially where it concerns prehistory; and we should not make so readily certain where the civilization of Europe began, nor limit its immense antiquity. But though it is a commonplace, and a true one, that all human work is subject to decay, there seems to be an inexplicable caprice in the method and choice of decay.

Consider what a body of written matter there must have been to instruct and maintain the technical excellence of Roman work. What a mass of books on engineering and on ship-building and on road-making; what quantities of tables and ready-reckoners, all that civilization must have produced and depended upon. Time has preserved much verse, and not only the best by any means, more prose, particularly the theological prose of the end of the Roman time. The technical stuff, which must, in the nature of things, have been indefinitely larger in amount, has (save in one or two instances and allusions) gone.

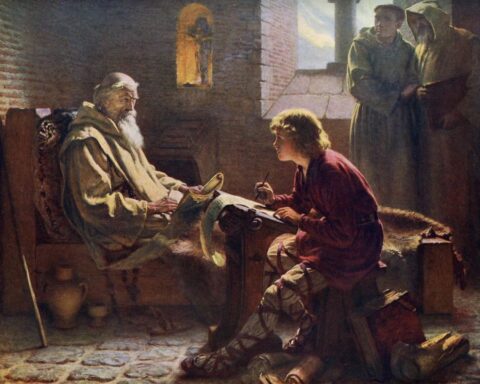

Consider, again, all that mass of seven hundred years which was called Carthage. It was not only seven hundred years of immense wealth, of oligarchic government, of a vast population, and of what so often goes with commerce and oligarchy — civil and internal peace. A few stones to prove the magnitude of its municipal work, a few ornaments, a few graves — all the rest is absolutely gone. A few days’ marches away there is an example I have quoted so often elsewhere that I am ashamed of referring to it again, but it does seem to me the most amazing example of historical loss in the world. It is the site of Hippo Regius. Here was St. Augustine’s town, one of the greatest and most populous of a Roman province. It was so large that an army of eighty thousand men could not contain it, and even with such a host its siege dragged on for a year. There is not a sign of that great town today.

A suburb, well without the walls — to be more accurate, a neighbouring village — carries on the name under the form of Bona, and that is all. A vast, fertile plain of black rich earth, now largely planted with vineyards, stands where Hippo stood. How can the stones have gone? How can it have been worth while to cart away the marble columns? Why are there no broken statues on such a ground, and no relics of the gods?

Nay, the wells are stopped up from which the people drank, and the lining of the wells is not to be discovered in the earth, and the foundations of the walls, and even the ornaments of the people and their coins, all these have been spirited away.

Then there are the roads. Consider that great road which reached from Amiens to the main port of Gaul, the Portus Itius at Boulogne. It is still in use. It was in use throughout the Middle Ages. Up that road the French Army marched to Crécy. It points straight to its goal upon the sea coast. Its whole purpose lay in reaching the goal. For some extraordinary reason, which I have never seen explained or even guessed at, there comes a point as it nears the coast where it suddenly ceases to be.

No sand has blown over it. It runs through no marshes; the land is firm and fertile. Why should that, the most important section of the great road which led northward from Rome, have failed, and have failed so recently, in the history of man? Where this great road crosses streams and might reasonably be lost, at its pontes, its bridges, it has remained, and is of such importance as to have given a name to a whole countryside — Ponthieu. But north of that it is gone.

Nearly every Roman road of Gaul and Britain presents something of the same puzzle in some parts of its course. It will run clear and followable enough, or form a modern highway for mile upon mile, and then not at a marsh where one would expect its disappearance, nor in some desolate place where it might have fallen out of use, but in the neighbourhood of a great city and at the very chief of its purpose, it is gone. It is so with the Stane Street that led up from the garrison of Chichester and linked it with the garrison of London. You can reconstruct it almost to a yard until you reach Epsom Downs. There you find it pointing to London Bridge, and remaining as clear as in any other part of its course: much clearer than in most other sections. But try to follow it on from Epsom Racecourse, and you entirely fail. The soil is the same; the conditions of that soil are excellent for its retention; but a year’s work has taught me that there is no reconstructing it save by hypothesis and guesswork from this point to the crossing of the Thames.

What happened to all that mass of local documents whereby we ought to be able to build up the territorial scheme and the landed regime of old France? Much remains, if you will, in the shape of chance charters and family papers. Even in the archives of Paris you can get enough to whet your curiosity. But not even in one narrow district can you obtain enough to reconstruct the whole truth. There is not a scholar in Europe who can tell you exactly how land was owned and held, even, let us say, on the estates of Rheims or by the family of Condé. And men are ready to quarrel as to how many peasants owned and how much of their present ownership was due to the Revolution, evidence has already become so wholly imperfect in that tiny stretch of historical time.

But, after all, perhaps one ought not to wonder too much that material things should thus capriciously vanish. Time, which has secured Timgad so that it looks like an unroofed city of yesterday, has swept and razed Laimboesis. The two towns were neighbours — one was taken and the other left — and there is no sort of reason any man can give for it. Perhaps one ought not too much to wonder, for a greater wonder still is the sudden evaporation and loss of the great movements of the human soul. That what our ancestors passionately believed or passionately disputed should, by their descendants in one generation or in two, become meaningless, absurd, or false–this is the greatest marvel and the greatest tragedy of all.