Editor’s note: The following comprises Chapter 20 of Children of Yesterday, by Jan Valtin (published 1946).

(Continued from Chapter 19: We Storm Corregidor)

The Division struck Mindanao like a thunderbolt. It struck with a hundred ships, with thousands of men, scores of field guns, hundreds of trucks. It struck where the Japanese least expected it to strike: at the town of Parang, in Moro Gulf, at dawn, April 17, 1945.

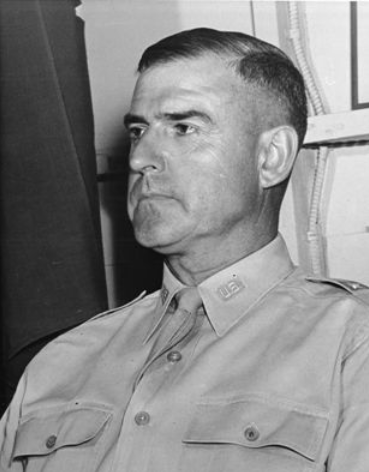

The Division convoy had steamed out of San Jose harbor, Mindoro Island, at 1300, Friday, April 13. Original plans had called for an invasion of Mindanao at the harbor of Malabang. However, a radio message received on the way had brought intelligence that the Malabang area had already been liberated by guerilla forces. Whereupon General Woodruff boldly changed his plan of invasion while the convoy was still on the high seas. Instead of landing at Malabang, he struck Parang.

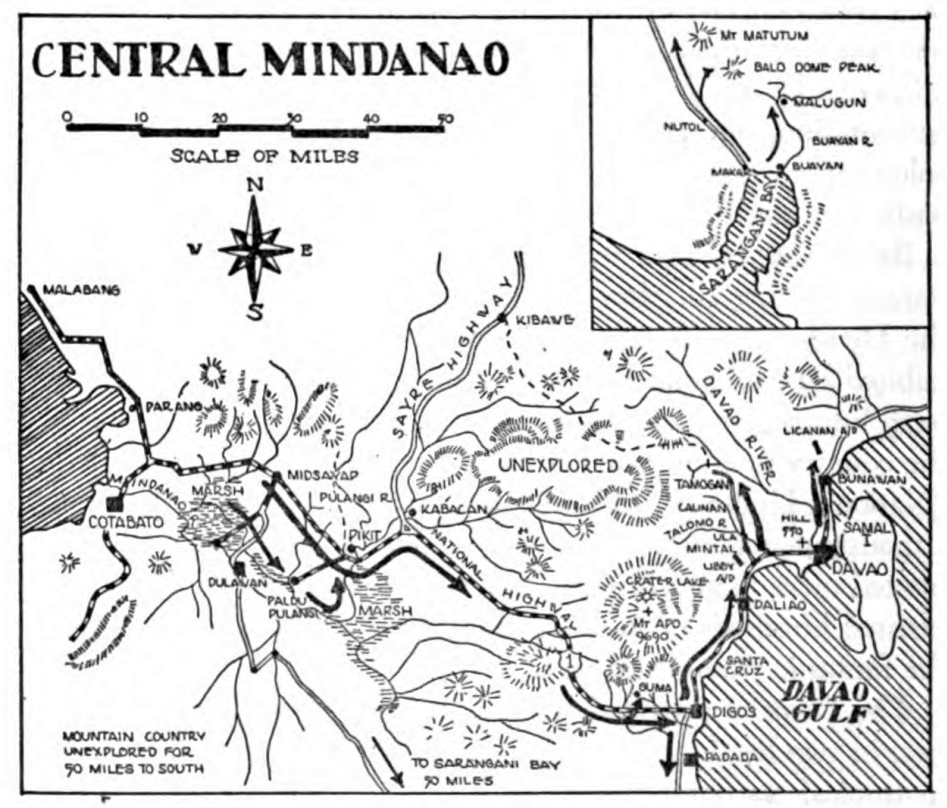

The Division’s goal was the city of Davao. At that time the bulk of an estimated 50,000 Japanese troops defending Mindanao were encamped in the Province of Davao, one hundred fifty miles east by trail from Parang. The naval base of Davao and the surrounding countryside has been for decades a hub of Japanese colonization. After the fall of Manila it was Nippon’s last major bastion in the Philippines.

Broad valleys, high mountains, belts of jungle, lay between Parang and Davao. More than fifty streams and rivers obstructed the Division’s advance. They flowed through wild country inhabited by Mohammedan Moros; and by tribes still addicted to head hunting and cannibalism. Maps depicted large expanses of the country in white patches and the legend “Unexplored.” The “National Highway” to Davao was mostly a one-lane track with a thousand-and-one twisting curves. The Japanese had burned or blasted more than a hundred bridges along the route. They had planted hundreds of mines, plotted scores of ambushes to delay the fantastic cross-island rush.

The Division pounded across Mindanao, from Parang to Davao, in two hectic weeks. It set an all-time record of mile-eating in tropical warfare.

The beach at Parang was narrow, black, steep. Jungle-covered ridges arose a hundred yards inland. The town of Parang was wrecked and deserted. Jap demolition, American bombs, Jap vengeance, American naval cannonade and rocket blasts and infantry invasion had driven the populace into the mountains. As the first waves stormed up the beach, a lone figure met them: a brown, sinewy woman clad in rags and armed with an old American rifle. When she saw the Division’s code letter “V,” painted on the jeeps and bulldozers, she raised two fingers of her right hand and said gravely, “Victoree — you are welcome.”

On that first day the Division seized Parang, Port Baras, Malabang airfield, and a thirty-five mile stretch of the coast. Assault companies forded three rivers and slogged five miles inshore. A 240-foot bridge across the Ambal River had been burned. Infantry waded through shoulder-deep with all weapons and ammunition that could be carried by hand. An amphibious reconnaissance group skirted southward along the shore and entered the gloomy estuary of the Mindanao River. It reported “many crocodiles but no Japs.” Combat engineers fell to and built new bridges almost overnight.

A soldier from New York and another from California slew the first two Japs of the new invasion. Sergeant Robert McKenzie of Syracuse and Sergeant Paul Salas of Richmond probed through a coastal swamp. They chanced upon a slit-like opening in the vines. Peering up at them were two Japanese armed with rifles and a copra sack full of grenades.

The New Yorker fired and killed one. The Californian heaved a grenade and killed the other. “Good work,” an officer commented.

“Reflex action,” said Bob McKenzie.

The first casualty in the invasion was Brooklyn’s Colonel William J. Verbeck. It was his fourth wound received in battle. The colonel had dipped a helmet full of water from a stream and he was washing his face in front of his regimental command post. In a nearby wrecked building lurked a sniper. The sniper fired as the colonel bent forward to rinse his face. That saved Verbeck’s life. The bullet plowed a flesh wound across the officer’s back.

Under a palm, digging beef from ration cans, sat three scouts with Tommy guns. They heard the shot followed by their colonel’s oath. A second later the Jap pitched head first out of the ruined building. A corpsman had jumped from an ambulance and shot the sniper. Submachine bullets riddled him before he struck the ground. Almost simultaneously, the Division Commander, General Woodruff, stepped into a spider-hole and came out swearing and with cracked ribs.

The first Americans to die in the last campaign of the Philippine war were victims of accidents. One night a green replacement crawled out of his foxhole to pee. A soldier in a neighboring hole saw movement in the dark and shot him dead. On another advanced night perimeter a soldier thought he heard a noise in a clump of bushes. He tossed a grenade. The grenade struck a palm trunk and bounced back into the thrower’s foxhole, where it exploded and killed him. A rifle squad had cornered four Japanese in a cave. The Japanese killed themselves with grenades. That same day, as the squad proceeded through an abaca field in single file, an eighteen-year-old infantryman committed suicide while marching by slipping a cocked grenade down the neck opening of his shirt. The blast tore him to pieces; it also killed the American marching to his immediate rear.

Lieutenant John Ebbets of Miami, Florida, poked around the ruins of Parang. In a half-smashed cubicle he found five carrier pigeons. Two had been killed by the concussions of the preparatory rocket barrage. Three were alive, but stunned. All of them had messages attached to their legs. John Ebbets called a Nisei soldier to translate the messages. The text of all was identical.

“The Americans are here,” it said.

That evening John Ebbets and the Nisei brewed pigeon stew. Both men were later killed in the storming of Mandog Hill, north of Davao.

An eighteen-ton tank-destroyer rumbled over the ramp of a landing craft. Its weight pressed the landing boat away from the shore. The big machine toppled into twenty feet of water. Inside it Corporal James Gibson from Oklahoma City tackled the problem of escaping death by drowning in an armored coffin. He came out alive. Three bulldozers towed the sunken destroyer ashore.

Through bizarre mountain passes the battalions thrust inland. The cross-island road, long unused, twisted like a corkscrew through a dark welter of jungle, immense trees, ravines, cliffs, tangled stream beds and inscrutable mountain sides. The sun blazed, and among the sinister ramparts of vegetation and house-high grass there stirred not the ghost of a breeze. Cases of heat exhaustion among the spearhead elements approached a hundred a day. Names like Simuay River, Tumbao, Dulauan, Lake Lanao were heard, passed and forgotten. An amphibious assault group seized the harbor of Cotabato, the Moro capital south of Parang.

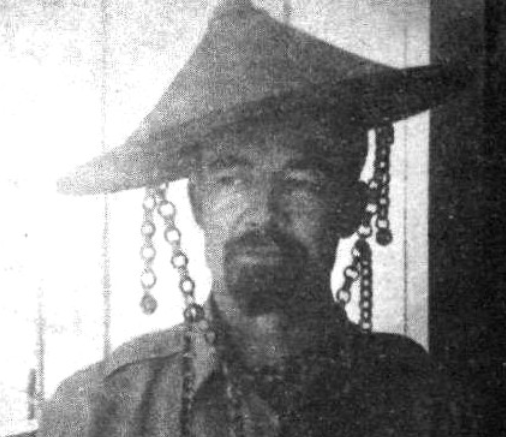

Throughout the Mindanao River country the guerilla organizations were strong. They were led by a former mining engineer, Colonel Wendell Fertig of Boulder, Colorado. Fertig had fought on Bataan when the Japanese invaded the Philippines in 1942. After the American surrender he had escaped by native banca to Mindanao and had become the driving brain behind guerilla doings in the islands’ south-west.

Enemy resistance in the first days of the Division’s drive was sporadic. Bridges burned. Ambushes flared. Nothing more. Nippon’s commanders had never reckoned that the drive on Davao could be made from the west, over abandoned mountain roads and half-explored wilderness. All fortifications and fire lanes along Mindanao’s “National Highway” faced east.

They all faced the wrong direction.

Sweating through a meadow of sword grass a four man patrol led by Sergeant Joseph Buckovich, of Brooklyn, followed a fresh-made trail. They came upon five Japanese. The Japs had been outraced by the American advance. Haggard and weary they lay asleep under a tree.

A volley killed the sleepers.

Then Buckovich heard a rustling in the grass beside him. A sixth Jap was trying to creep away. Joe shot him through the head.

“This field is crawling with Japs,” he said slowly. “Let’s give her a good spray.”

Every man in the patrol opened rapid fire. Bullets swished through the grass in all directions. There came screams and Japs charging in frantic groups of two and three. A bullet knocked the rifle from Buckovich’s hand.

When it was over they counted. There were eighteen corpses.

Lieutenant Robert Drennan of Rock Hill, South Carolina, was passing through a mountain barrio at the head of his platoon. A shaggy native accosted him. The Moro waved a paper in front of the officer’s face.

“What’s that?” asked Drennan.

“You from Nineteenth Infantry?”

“How do you know?” Drennan demanded.

“Please read the paper, sir,” the native said.

Drennan read. It was a discharge certificate from the Nineteenth Infantry Regiment, issued in Hawaii, in 1924, to Private Maximo Cabayan.

The islander pounded his chest. “I am Maximo Cabayan,” he announced. “I weesh to serve my old outfit.”

Bob Drennan made him an interpreter and scout.

A Nineteenth Infantry battalion commanded by Lt. Col. Joy K. Vallery of Lincoln, Nebraska, came to a raging river in the middle of a rain-filled night. Engineers had improvised a foot bridge one hundred feet long. The nine hundred men of the battalion negotiated the crossing one by one. For the first fifty feet they inched along a log, with another, higher log serving as a hand hold. For the next fifty feet it was the same, except that the hand hold disappeared. One steel helmet was lost.

The river, it was found later, was the home of many crocodiles.

A bridge guard crouched in the rain. Peering over the rim of his hole he could discern the road only as a dim ribbon which vanished in darkness five yards away.

Suddenly a grenade exploded at the water’s edge.

Corporal J. W. Owensby took no chances. He had in his belt twelve clips of ammunition— ninety-six rounds. He spent the hours until dawn firing down the roadside ditches. His shots went into complete darkness. At dawn he found a dead Japanese three yards from his foxhole.

Sergeant Charles Worthington of Compton, Kansas, wanted to take a prisoner. His platoon slogged down the road which at this spot spiraled into a canyon. Scouts ranged ahead. Ahead and below them lay a stream bed.

Abruptly the lead scout stopped. He had seen a bush by the stream bank jerk to cover behind a large tree. It became a question of who ambushed whom. The patrol moved stealthily through flanking thickets. Its men then waded along the stream. They pounced on the enemy from the rear. Two Japs were killed. Three committed hara-kiri by grenade. One ran.

Charles Worthington chased the running Jap. He wanted a prisoner. His pursuit was so rapid that he could not come to a quick halt when his quarry suddenly turned and cocked a grenade. Worthington swerved sideways and pitched headlong into a swamp. He held his breath and waited for the grenade. But the Jap had other intentions. He held the grenade to his stomach and bowed. The grenade exploded.

Machine gunner Arthur Imm of Long Island, Kansas, was a night perimeter guard for a battery of field artillery. He sat in a shallow foxhole at the edge of the cannoneers’ bivouac and stared into the darkness. Forty feet away the jungle stood like a mysterious wall.

A half hour before midnight the gunner felt that something was moving in front of him. He trained his gun and fired a burst of six rounds.

A bird screeched. Nothing moved.

Next morning he found a Japanese soldier with six holes in his neck. Strapped around the dead man were two land mines, eight grenades and a bangalore torpedo four feet long. The cannoneers now call their guard “Dead Eye Imm.”

Sergeant Robert Savidge of Los Angeles led a detail carrying rations to the perimeter of a spearhead patrol. One of his men detected movement in the jungle twilight. They all threw themselves flat on the ground, their rifles ready. Something was prowling through the foliage.

“Holy cats,” whispered Private Francis Ridge, of Sacramento, California, “I can see ’em. They’re camouflaged with fur coats.”

He pointed, and Robert Savidge followed the direction with his eyes.

“Dope,” he said. “That’s apes.”

When the ration detail reached their destination after a five mile march, scouts of the spearhead patrol recounted how “some kind of man-sized monkeys” had set off booby traps around their perimeter during the previous night.

In the advance across Mindanao the Division’s vanguard by passed many Japanese detachments. The Japs, when overtaken, faded into the flanking jungle. Ten yards away from the trails they were safe and unseen. They then slept during the day and banded together for raids under cover of darkness.

Sergeant James Keeses of Winchester, Ohio, marched with a patrol which had traversed fifteen miles of jungle in a search for Japanese bivouacs. On the third night of their mission the patrol was attacked.

The attacking Japs wore knee-length nets entwined with leafy twigs. In the dark the keenest eye could not distinguish them from bushes. They crept to within ten feet of the patrol’s camp before they jumped up and rushed with shrill cries. Two Americans were bayoneted before the fire power of automatic rifles could be brought to bear.

Hard in the wake of the trail-blazing infantry and combat engineers rolled trucks, ambulances, bulldozers and artillery; and with the artillery came the Cub planes of the artillery observers. But with each nightfall all traffic stopped and all units dug fox holes and posted perimeter guards. The holes of the perimeter guards were separated from one another by but a few paces. Still, Japs managed to creep through at night.

Lieutenant Robert Price of Skiatook, Oklahoma, was an artillery observation flier. He parked his Piper Cub inside the perimeter and went to sleep beneath an artillery truck.

Toward midnight he heard a flurry of footfalls. Price grasped his pistol. A moment later a bomb exploded. Debris fluttered out of the night. The officer saw three shadowy figures run past the truck. He emptied his pistol. Two Japs died. The third escaped. The Piper Cub plane was a mass of brightly burning wreckage.

One morning a guerilla wearing a Notre Dame University basketball shirt and an American Legion cap walked into an advanced perimeter. He told the commander that he knew of an enemy bivouac two miles off the Division’s left flank.

“How many Japs?” he was asked.

“About three hundred,” he said.

It seemed a worthwhile artillery target.

But the guerilla was unable to pinpoint the location of the bivouac on a military map. It was decided to send him aloft in a Cub plane. A sergeant from Portland, Oregon, guided the native warrior into a plane. They took off from the road. In the flight over the mountains the guerilla became violently sick. His face turned green. Fright wrinkled his face as the Cub swept low over the tangled wilderness below. He also became enormously excited.

“If you touch the controls,” the sergeant warned, “I must knock you out.”

The guerilla calmed down. He motioned the pilot onward with expressive hands. Then his eyes gleamed. He had spotted the bivouac.

The sergeant radioed. Shells screamed over the jungles. The guerilla rolled with laughter when he saw the Japs flee like hares from the area of explosions.

“If you don’t sit still,” the sergeant warned him again, “I must knock you out.”

The company slogged through the seventh hour that day on their forced march on Davao. The faces of the men were drawn and their uniforms were black with sweat. Packs were heavy and weapons heavier. The muzzles of a hundred rifles and submachine guns were pointed at the barriers of jungle while their bearers marched.

Scouts signaled a warning. There was a faint crunching in the thickets. The company swarmed off the road. In two seconds the road was empty. Fingers rested on triggers of a hundred rifles and submachine guns.

Out of the forest stalked a lean, barefooted woman. About her were five skinny children. The legs of all were covered with sores. The woman looked steadily up and down the empty road, at the gun muzzles in the roadside ditches.

“Don’t kill,” she said. “Only medicines I want.”

The soldiers relaxed. They sprawled at the edge of the green barricades and rested while their aid man, Albert Wright of Seattle, treated the jungle rot on the skinny brown legs.

“Movement is very difficult due to intense heat in the high grass which has overgrown the road. A distance of twelve road miles was covered during the period.”

(from a Field Report, April 20)

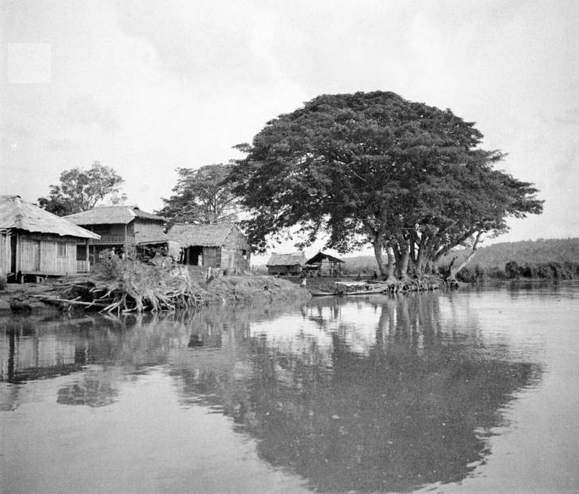

Where the trans-Mindanao road crosses the broad Mindanao River the mountains and jungles give way to a wide central valley. There are rolling expanses of kunai grass, palm plantations untended for years, banana groves and abaca fields denser than any jungle can be. At the junction of road and river lies Fort Pikit.

On November 19 planes ranging over Fort Pikit were greeted by machine gun fire. Observers saw that the big steel bridge was blasted, its span sunken in the river. The planes strafed the fort and its surroundings with incendiary shells. When they departed the fort was burning, adjoining barracks were afire, and a Jap supply truck had gone up in flames.

That day, in the march on Fort Pikit, the Nineteenth Infantry vanguard skirmished with twenty-five Japs and killed eighteen. They captured three trucks. The trucks had been camouflaged to look like bushes. At nightfall the advance guard engaged a band of thirty Japs in a fire fight. The ambush was destroyed. Thirteen enemies were killed.

Twenty-First Regiment patrols contacted eighty Japs near the village of Lomopog and killed eighteen. Canoe patrols in the estuary of the Mindanao River killed two more.

Two Americans died in action that day, and five fell wounded.

A day later the Nineteenth Regiment crossed the Libungan River. The bridge had been burned. The river is three hundred feet wide and too deep to be forded. The riflemen built rafts. A team of swimmers carried a cable to the far bank and the regiment crossed the river on cable-drawn rafts. In a fire fight three Japanese trucks were wrecked. Five trucks were captured intact. Of these five, three were found booby-trapped with grenades. The traps were disarmed. The trucks were put to immediate use, U.S. ARMY . DON’T SHOOT chalked onto their sides.

Infantrymen seized the town of Midsayap. They captured two hidden supply dumps which contained mortar and artillery ammunition, grenades, two hundred American rifles, motor fuel, dynamite and twelve tons of rice.

Reconnaissance groups of the Thirty-Fourth Regiment captured Fort Pikit in a surprise thrust up the Mindanao River. On shallow-draft barges they mounted captured Japanese machine guns, cannon and rocket guns salvaged from wrecked American planes. They piloted these “home-made” gunboats up sixty miles of crocodile-ridden river courses, past dark swamplands and over muddy shallows. They appeared off Fort Pikit like men from Mars, all armament blazing. Their radio message astounded the Division’s planners.

“Stormed Fort Pikit,” the message said. “Hoisted flag. Awaiting infantry.”

Soon a fleet of landing craft was on its way upstream from Cotabato to ferry heavy equipment across the Mindanao River. The whole Thirty-Fourth Infantry Regiment marched seven miles to a river town named Paidu-Pulangi. On the way some of the riflemen swapped rifle ammunition for fine Moro swords. The proud and never-conquered Moros used this ammunition to shoot Americans and Japs alike. In Paidu-Pulangi the regiment boarded ocean going assault ships (LCI’s) and pushed upriver to Fort Pikit. General Woodruff boldly accepted hazards that would have frightened off a more cautious commander. The trip was an adventurous exploitation of the river highway in spite of sand bars and many hairpin turns. The ships’ sides plowed the flanking jungle and the Navy crews had the novel experience of sweeping jungle foliage from the decks of their ships. At one spot gunners detected movement behind a promontory in the river. They promptly opened fire. Around the bend an Army gunboat was surprised by the sudden overhead bursts and quickly replied in kind. The Army-Navy duel ended when the ships met head on in the bend of the river.

Unloading at Fort Pikit, the men of the Thirty-Fourth Regiment — who two months earlier had stormed Corregidor from the sea — became the overland battering ram of the Division. They swept twenty miles eastward and overran Kabakan on April 22. Kabakan is the cross-roads of the east-west and north-south high ways of central Mindanao. Blasting ambushes, circling burning bridges, and fording rivers the riflemen speared eastward out of Kabakan and penetrated Saguing, thirty miles from Davao Gulf, on April 24, far beyond the reach of supporting artillery. They pushed through immense swarms of locusts. Through whirring insect clouds they approached a bridge which seemed intact. The Japs blew it up into their faces.

A Moro wearing a wine-red turban and a magnificent curved gold and ivory dagger wandered into “Fox” Company’s perimeter. He asked to see the “commandant.”

“Any Japs?” the company commander asked him.

‘Yes, sir.” The Moslem pointed toward the river. ‘Two thousand yards from here I see seventy-five Japanese soldiers, sir.”

“What were they doing?”

“Some cook rice, some sleep. They make me chop wood.”

“What’s the place like?”

“Bamboo,” the Moro said.

“Fox” Company was alerted and pushed toward a bamboo forest on the south bank of the Mindanao River. Stealthily they surrounded the bamboo. But abruptly mortar shells rained from nowhere. The shells covered every square yard of the bamboo grove with a checkerboard of explosions. “A trap,” the company commander growled. “Where’s that native bait?” The Moro had vanished.

As the company withdrew from the barrage a howl arose out of an expanse of sword grass on its right. A company of Japanese rushed out of the grass in a flanking attack. The Japs charged with bayonets fixed, with grenades, spears and sabers. “Fox” Company quickly fell back to safer ground.

On the left flank, a 36-year-old German-American, Private William Roepke, of Philadelphia, did not hear the command to retreat. He lay behind a bamboo tree and held his ground. At the time he did not know that many Japanese were armed with captured American rifles. He heard the heavy barks of the Enfields and he was happy.

Roepke was of a stalwart breed. His blond mustache bristled. He held his post for three hours and then the yelling and shooting stopped. After another hour he became aware that his company had retreated and that he was alone in the rear of the Japanese lines. He stood up to peer through the underbrush and what he saw was Japs. He ducked low and did not move from the spot.

Morning wore on into afternoon and the sun covered the land with brooding heat. Roepke drank the last water in his canteen and waited. He was thirsty. Thirst waxed into torture. He could hear the Japanese jabber among the bamboo and kunai but he could not see more than four feet in any direction. The sun set and the Japs pitched camp and Bill Roepke found himself marooned in the middle of an enemy bivouac. He heard the Japs kill chickens and cook rice and defecate, and he heard them clean their weapons. Darkness fell and Roepke did not dare to move. Each hour the enemy guards exchanged hissing cries to assure each other that they were awake. Enemy patrols came and went. Roepke was exhausted and half out of his mind from the day-long hammer blows of the sun upon his helmet. Heavy rains fell during the night. Bill Roepke buried himself in mud and rested.

Came dawn and another day. The lone soldier was ragged and dirty and hungry and he felt a pile-driver pounding in his brain. His cocky blond mustache was gray and drooping.

He decided to shoot his way out. He stood up and staggered toward the river through grass thickets eight feet high. He passed groups of Japanese squatting in his path. But he could not bring himself to shoot at them unless they first saw him. “Hallo,” he said roughly. The Japs turned, startled, and Roepke fired. He killed thirteen Japanese before he reached the river.

He dived into the river and let the current carry him away. He knew that there were crocodiles in the river. He lay there, floating on his back, looking at the sky, and tried to drown his fear by singing German songs. A native in a canoe rescued him. The Filipino paddled him to the nearest camp. Soldiers on the perimeter stared at the gaunt apparition.

Bill Roepke stumbled between the line of foxholes and collapsed.

“I ate a lot of Yaps for breakfast,” he mumbled.

A Jap bombing plane appeared over Division headquarters at 6 A.M. and went into a dive. The general and his aides were awakened by a roar of machine gun fire. The plane swept away, circled, dived again. Again it was driven off. The enemy pilot then spotted a team of wiremen stringing telephone wires along the roadside thickets. He dived on the wire party and dropped a 500-pound bomb.

A crater opened in the road.

There were many craters in the road, put there by American planes bombing columns of fleeing Japanese and by Japanese mines. The Japanese, knocked off balance by this stormwind advance “from the wrong direction,” were fleeing toward Davao. The Division’s pace gave them no time to build fortifications facing west. The road was lined with cunningly hidden emplacements, but they were useless to the Japs; their fire lanes pointed east, toward Davao. The fleeing Japs left burning bridges, burning barracks, burning supply dumps and burning trucks.

A group of Japanese civilians trudging toward Davao was overtaken by footsore patrols. There were thirty. There were twenty thousand more in Davao. Among those caught there was a mother with six children. “Americans,” the mother asked, “after you have killed me, will you take care of my children?”

An artillery corporal reached into his pack. “Here, lady,” he said. “Better take these rations. Your kids look hungry.”

Mines!

Between Fort Pikit and Davao the Japanese had mined the road with many hundreds of aerial bombs. The bombs were buried so that only an inch of their noses showed above ground. Wires attached to the detonating mechanism led forty to fifty yards to foxholes dug in the flanking jungle. And in each fox hole sat a Jap. A tug upon the wire would set off an explosion violent enough to blow a hundred men to death.

The first bomb-mine encountered was made to naught by Jap eagerness. A squad led by Sergeant Clifford Barnes of Oakfield, Wisconsin, received sudden machine gun fire from the front. In a split second the soldiers sought cover. It was only a moment later that other Japs pulled a hidden wire and detonated a bomb buried thirty yards ahead of Clifford Barnes. The members of the squad were stunned by the concussion. But except for bruises caused by flying pieces of road and vegetation they were unhurt.

Barnes silently thanked the enemy gunners. Had they not prematurely opened fire, his squad would have been caught standing upright on the road. Not one would have escaped alive. He heard a Japanese officer in the bushes berate his men for yanking the wires too soon.

Now mortars accompanied the vanguard platoons. Their shells set the roadside jungle afire and drove the wire pullers out of their holes. Combat engineers marked buried bombs with bits of paper propped on sticks, and past them and around them the advance rolled on.

The Japanese on the road to Davao were of many units. Japs name their fighting teams after their commanders. There was the Harada Unit and the Suzuki Unit. There were members of the Tanaka and Watari Units. There were first line infantry troops, the 100th Imperial Division, Japs from labor battalions, the crews of sunken naval vessels, Imperial Marines, native conscripts and volunteers from Davao, and aviation personnel fighting as foot troops.

Hidden in grass huts and tunnels patrols captured nineteen cases of hand grenades, seventy naval torpedoes, forty aerial bombs, twenty-two mines — the first of vastly larger hauls to come.

General Woodruff had reason to be satisfied. Satisfied with his men and with himself. Hard-striking troops giving their utmost; audacity of command and bold self-confidence; those were the elements which made possible one Division’s apparently foolhardy dash across an island manned by the numerical equal of three enemy divisions. The corridor carved out of Mindanao was less than one mile wide. Communications and supply lines from Parang were long, vulnerable and only thinly held. Night ambushes on rear communication lines became a common occurrence. But it was no rarity in this campaign to see patrols of rifle men dart off the road to make room for a speeding jeep driven by their commanding general deep in Jap country; a jouncing little car, the burly, dusty, mustached Texan behind the wheel, three bodyguards with submachine guns perched on the remaining seats.

Not to be outdone by the general was the Division Chaplain, Major Paul Slavik of New York. He, too, drove his own jeep, ever on the move to “visit the men up front.” One Sunday General Woodruff’s car was stopped by a burning bridge. On the far end of the bridge stood another jeep, the chaplain’s, and arms akimbo, the two men exchanged greetings across the blazing timbers.

“Chaplain,” rumbled the general. “I see you in the damndest places! How’d you get across?”

“This bridge was all right when I drove over it a little while ago,” the chaplain said.

The general sought a by-pass. He nosed his jeep down a steep bank, half rolling, half sliding, and miraculously made it climb the other side.

He asked the chaplain, “See any Japs?”

Slavik shook his head. Woodruff wiped the sweat from his face. He stepped on the accelerator.

“What a hell of a way to spend a Sabbath,” he growled. Seconds later the chaplain saw him vanish in a cloud of dust in the direction of Davao.

In a clear mountain stream, beneath the charred and still smoking bridge, a combat patrol of twenty stripped to bathe. The soldiers left their clothes and their weapons on the bank and plunged into the water.

Without warning, without as much as a splash, a lone Japanese slipped around a nearby bend in the stream. His light machinegun spat lead.

The bathers scattered into the underbrush. All were naked. Some were covered with soap suds. None was armed.

It did not occur to the lone Jap that twenty American rifles lay unguarded only a little way off. He stopped in the stream bed and sprayed the thickets. That gave two of the bathers a chance to crawl to their rifles. The Jap died.

Soldiers speaking:

Private First Class George Mahnke, Napoleon, Ohio: Nips are stubborn unto death. I was on patrol and we were stopped all of a sudden by mortar fire which came from a banana plantation. After about twenty shells the Japs stopped firing their mortars. They came rushing at us in a bunch, yelling, swinging their bayonets and shooting their rifles. We broke up the charge with our own fire. But after a few minutes they charged again, yelling “Banzai!” Our B.A.R.’s mowed them down. Instead of going back to their mortars the fools rushed us a third time. The last of the lot died feet in front of our firing line. We counted forty-six dead Nips. We had one man wounded by a hand grenade.

Private First Class Joseph Reed, Adrian, Michigan: I was the lead scout of a ten-man patrol. I came to a quick-flowing river and stopped. The bridge was out and still smoking. I lay there for a minute or so and studied the bushes on the far bank. Japs like to set up ambushes at river crossings. They let the scout pass and wait until the body of the patrol is wading in the middle of the river. Then they cut loose. Sure enough, there was the muzzle of a machine gun sticking through the leaves. The Japs saw that I saw them and they opened fire. My patrol leader was hit. We then called for mortar fire on the machine gun nest. The shells set the bushes ablaze and the Nips disappeared.

Sergeant Eugene Rink, Huntington Park, California: I was guarding a bridge in the night. It was raining hard. I felt a blinding glare when a Jap rifle butt came crashing down on my helmet. The Jap thought I was dead. First he kicked me. Then he stepped over me and crept onto the bridge. But the rain beating in my face brought me out of the daze. I shot the Jap and then I raised my head and listened. There was a rustle in the brush and it wasn’t the rain. I let fly with a grenade and I heard somebody groan. Before morning a third Jap came around. I shot him. By dawn I had a pretty bad headache.

Cannoneer John Lozinak, Eckley, Pennsylvania: My artillery battalion displaced forward every day. The supply line up from Moro Gulf was a hundred miles long, with the jungle on both sides still filthy with Japs. They liked to creep up to the road-side with sacks of dynamite to blow up our ammunition trucks. One day I was patrolling a five-mile stretch of road in a jeep. A Moro came up to me and said: “Jap officer hide in cave over there.” He pointed. I went over to the cave, and hollered for the yellow-belly to come out. Nothing moved. I threw a grenade into the cave. When the smoke cleared away I crawled into the cave, my Tommy gun at the ready. There was a pistol shot and I let the Nip have a long burst. The cave was full of mines. I can’t figure out why they didn’t blow up when my grenade went off. I got a Jap saber out of it, a bit shot up, but still good.

Sergeant Paul Brennan, Great Kills, New York: I was riding an ammunition truck behind our lines. We were rounding a bend in the road when suddenly three Japs jumped out of the bushes and threw a mine in the path of the truck. The mine exploded. One of my buddies was blown off the truck. A front wheel was blown off and sailed fifty yards through space. We dived off the truck and into the jungle and every second of it we fired wild in all directions. When things quieted down we looked around. There were nine dead Japs in the bushes.

Private David T. Aldrine, Paola, Kansas: I was with a four-man patrol in the jungle. With us was a Jap-speaking guerilla guide. Near a river a machine gun fired in our direction. The Nips did not see us, they fired by sound. The guide and I wriggled forward and I killed the Jap gunner with two shots. Then we heard somebody shout an order. I asked our guide, “What did that Jap say?” The guerilla translated: “Squad to the right, squad to the left, advance!” So I started shouting too. “Send up the company,” I shouted. My two buddies in the rear caught on. They repeated the shout. “Send up the company.” The Japs thought a whole company was coming for them. They stayed where they were and we could hear them digging in a hurry. That saved our patrol.

Lieutenant McCullough B. Lewis, Los Angeles, California: I was returning from the front with a convoy of three trucks that had taken up hot food for the men. We came to a spot where the jungle grew over the road like the top of a tunnel. A Jap ambush squad threw a bangalore torpedo out of the jungle in front of the lead truck. The truck ran over it. The torpedo failed to explode. Nine of us piled out of the trucks and went after the Japs. I shot two. Then a grenade blast knocked me down. When I raised my head I saw the muzzle of a Jap rifle one foot away from me. It was pointing at my heart. I stared and the hammer fell. A click. Misfire! I did not give the fellow a chance to pull his bolt for a second shot.

On April 27 the Division vanguard penetrated Digos Town, not far from the Gulf of Davao. They crossed several streams before they met bitter resistance. The bridges across all streams were “out.” One was destroyed by shell fire; one was found burning; the third, spanning the Digos River, had been craftily mined. Its timbers were almost sawn through, and seven mines had been attached to the cuts.

The road was heavily mined with aerial bombs. One of the mines blew up an armored reconnaissance car. Another mine, booby-trapped with a fountain pen, was set off fifty yards in front of the assistant Division commander’s speeding jeep. General Cramer escaped unhurt. In turn, American planes bombed two Japanese truck convoys heading toward Davao under cover of darkness.

Ninety-four Japanese were killed on the approaches to Digos. The survivors fled toward the coast. Said one footsore infantryman: “I wish the Nips would stand a bit longer so that we could get some rest.”

South-eastern Mindanao has long been a center of Japanese influence. Before the Division’s sweep, hordes of Japanese civilians were fleeing pell-mell toward Davao. Observation planes reported long, ragged columns trudging eastward. The enemy civilians had stripped their dwellings and left them burning. They had killed all their livestock. In some of the half-burned huts and barracks roast chicken stood untouched on charred tables. Among captured equipment that day were fifteen trucks loaded with rice; hundreds of grenades; cases of sake, sewing machines, spears, war clubs, knives and pictures of Nipponese glory.

A jeep occupied by three artillery officers bounced around a road bend and collided head on with a Japanese troop truck heading in the opposite direction. There were some fifteen astonished Japanese in the truck. The officers scrambled out of the jeep and dashed into the jungle. After a wild volley of shots the Jap truck turned and sped the way it had come. The officers climbed back into their jeep. They continued on their mission of finding new firing positions for their advancing artillery.

Dawn broke over the roadside foxhole.

“See that Jap I got last night,” said Private Clarence Ralph of Fisher, Illinois.

His comrade peered over the rim of the hole.

“Hell,” he said. “You got two.”

“Nope, only one,” said Ralph.

“Well, there are two Japs lying out there.”

“Then one of them’s alive.”

Clarence Ralph raised his rifle. A much-alive Jap jumped to his feet and charged with a grenade. Ralph fired eight shots in swift succession. His score was two.

Communications Sergeant Tom Saunders from Somerset, Ohio, knew that Japs liked to cut telephone lines at night, then lie in ambush to lull the linemen who came to repair the break. So Saunders sent a guerilla scout ahead to investigate the terrain adjoining the break. Moro guerillas are the finest jungle fighters in the world. In noiseless and skillful crawling they outdo the most skilled Jap. The scout reported four Japanese lying in ambush. Saunders and his telephone crew circled the spot and shot them to death. In the enemy emplacement they found bangalore torpedoes, rifles, mines and seven wires which ran to seven 500 pound bombs buried overnight along the road.

Guarding one of the many makeshift bridges at night, Corporal Melvin Norwood of Glencoe, Alabama, heard a slurring noise at the edge of his foxhole. Norwood reached for the safety release of his automatic rifle. He touched the wrong release and his cartridge magazine dropped from the weapon instead.

With one cartridge in the chamber of his B.A.R., Norwood released the safety and fired. A Jap soldier crumpled so close that his head hung over the rim of the bridge guard’s foxhole.

Hearing the shot, other Japs sprang up and charged. But Norwood had had time to reload. The B.A.R. clattered as only a B.A.R. can clatter in a dark night. The attackers faded away. At dawn there were three — dead.

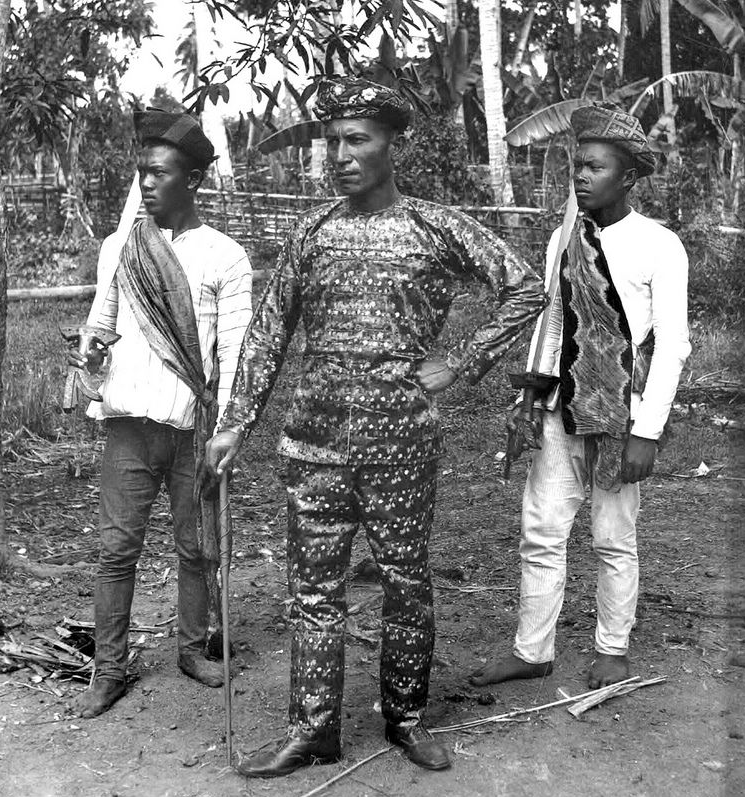

The Moros of Mindanao remained a question mark through out the campaign. Fine silversmiths and sword makers, they are also expert killers. They are the proudest, most untamed, most self-confident people of the tropical mountains. Like most Mohammedans they have little fear of death. They made war on Filipinos, Japanese and Americans alike. A Filipino guerilla party stalking a Japanese bivouac was ambushed by Moros. The Moros killed the Filipinos and cut off their heads. Then they took the weapons they had captured from the Filipinos and used them to kill Japs.

There was a Moro who, having heard of vitamins, liked to eat the livers of the Japs killed in battle.

The Moros are also an extremely moral people. Their code forbids a stranger even to touch the hand of a Moro woman. On the road to Davao a battalion surgeon gave this advice: “Keep your penis in your pants and the Moro will keep his kris inside his sheath.”

Among other tribes on Mindanao are the Manobos. They are wild pagans, tree dwellers with no reputation for peaceful ways. They are stalwart, meat eating people. Their hair is long, their teeth filed flat.

There are the Bagobos, a primitive pagan tribe of the unexplored hinterland of Davao; before American artillery came their way they dwelled on the slopes of towering Mount Apo.

There are the Negritos, small, pitch-black, with broad heads and thick lips, and armed with blow-pipes shooting arrows poisoned with the juice of upas trees.

And there were the Japanese of Davao. Long established in the Philippines, they were Japanese loyalists at heart, and they had transformed the Davao Gulf country into a prosperous miniature Japan. They had established huge abaca plantations, fisheries and lumbering industries. They controlled the commerce of Davao City, the schools, newspapers and banks.

In the Division’s battle teams men asked one another, “What about the civilians of Davao? Will they be quiet? Will they fight side by side with the Jap troops? Will they commit mass suicide as on Saipan?”

Nobody knew — as yet.

On April 28 — after a twelve-hour, two-battalion battle — the men of the spearhead patrols saw the glittering blue of the ocean as they crossed the mountain passes of the eastern range. They were soldiers of the Thirty-Fourth Infantry Regiment, the first to cross Mindanao Island from coast to coast. They secured the Digos beaches and the airfield of Padada. The beaches had been intricately fortified. The fortifications were abandoned. The fire lanes of all emplacements faced the sea — Davao Gulf — whence the American invasion was expected. The Japanese command had planned a bitter beach defense and a fighting withdrawal from east to west into mountains. Their intended line of withdrawal had been the line of the Division’s advance. Mindanao was now cut in two.

Forty miles to the north lay the city of Davao.

Battle teams of the “Rock of Chickamauga,” led by Colonel Clifford, passed through Digos and pounded north along the coastal highway. They seized Toban and Santa Cruz. They captured heavy naval guns mounted in beach positions facing the sea. They smashed three turret-like pillboxes camouflaged with beds of bright red flowers. They captured warehouses crammed with supplies ranging from naval torpedoes to electric fans.

Soldiers speaking:

Sergeant S. T. Dewhirst from Portola, California: I drove along the beach road in a jeep. All of a sudden a Jap sprang out of the bushes and threw a mine under the jeep. The mine exploded and the jeep was wrecked. My companion was badly hurt. I was dazed. But I recovered in time to shoot the Nip five times with my pistol. He was still on his feet and he kept running. While running he pulled out a razor and cut his own throat.

Another jeep came along and another Jap darted from the bushes and threw a mine. The driver swerved around the mine and the Jap disappeared.

Private First Class Harold Jones from Ainsworth, Nebraska: I am a machine gunner. We had just broken up a night Banzai attack and all was quiet again. My gun had jammed toward the end of the attack, so I cleaned it and reloaded. Then I dipped the muzzle a little bit to the ground and fired three shots to see if she worked all right. A squeal followed the burst. I had shot a sneaking Nip by accident. Two hours later he woke me up with his moaning. So I gave him another burst to put him out.

Lieutenant Dan Bradley from Detroit, Michigan: My job is to fly a dive bomber. A few miles from Davao my ship caught fire. I was flying at a low altitude. I tried to get my landing wheels down. They wouldn’t go down. Then I started for a belly crash, but flames made that impossible. I nosed the burning plane into a climb and bailed out. But I pulled the rip cord too soon. The chute caught in the tail of the plane. I saw the ground rush to ward me and I tried to jerk the chute clear of the falling ship. Suddenly the plane rolled over and the chute rifled free. I landed hard in an abaca thicket. All I got were scorches and bruises. Later I figured out how my plane caught fire. It was from the blast of a bomb dropped by another plane flying in front.

Captain Julien C. Mason, of Colonial Beach, West Virginia: I’m a civil affairs officer for the Division. Of the many problems that loaded me down when we swept across Mindanao one in particular was a stumper. A Moro chieftain of doubtful loyalty had two sons. One was a provincial governor for the Japanese. The other was a very good guerilla leader. The question was, should we leave their old man in power or not? I solved that problem — I turned it over to higher headquarters to decide.

Sergeant James J. Thompson from Oakland, California: I was leading an advance patrol toward Davao when I spotted a Jap pillbox. I warned my men down. I unloosened a grenade and crawled toward the pillbox. I was just about to toss the grenade into the mouth of the dugout. A thin little wail froze my arm. I listened. The wailing came again. It came from the pillbox. It could have been a trap but it sounded too real. I crept closer and peered into the pillbox. There was a crying baby inside. There were four people in the dugout. An old man and he was shot dead. A young man and he was shot dead too. A young woman stabbed in the belly three times with a bayonet but still weakly alive. A six-months-old baby stabbed once through the belly. The young woman explained: They had tried to flee over to the American side. Japs had caught them. Then they had thrown the whole family into the pillbox.

Captain Paul E. Byrd of West Fargo, North Dakota; Medical Department: At 3 A.M., I was roused by an emergency call from the forward elements. They needed blood plasma in a hurry. So five of us secured the plasma and climbed into a jeep. We dashed over ten miles of pitch-dark road, past jungle, mountain curves and through rugged by-passes around destroyed bridges. We delivered the plasma. But on the way back we were ambushed. Japs fired from roadside thickets with machine guns. Their bullets crashed through the front of the jeep and wounded four of us. The driver had stopped and now he was backing away down the road. Those of us who could still stand jumped out and gave battle. An infantry night patrol came along and chased the Japs into the jungle. There were seventeen bullet holes in the jeep.

Corporal Tony Mulay of Pueblo, Colorado, Corpsman: The yell “Aid man! Aid man!” is the time-honored SOS of the battle field. On the road to Davao I fixed up some wounded boys. I fixed up wounded boys in battle before this, in New Guinea, Leyte, Luzon, between seventy-five and a hundred of them. They got so used to me that when they need me they don’t shout, “Aid man!” They shout, “Tony! oh, Tony, come over here quick.” Well, I come. They say sometimes the Japs were shooting at me while I worked. If they did, I didn’t notice. You see, I’m pretty busy.

Private First Class Alphonso DeLeon of San Antonio, Texas: I was with a patrol probing into Jap country around Davao. There were some Nips in ambush but we did not see them first. I was the last man in the patrol. The Nips let the patrol pass and then one of them leaped from the bushes and shoved his bayonet into my right side. My own rifle was slung over my shoulder. I whirled and grabbed the Jap’s rifle. At the same time my own rifle slipped to the ground. I knocked the Jap back into the bushes. I then tried to shoot him but the Jap’s rifle would not work. Disgusted, I slammed the muzzle to the ground and the bayonet broke off clean. That moment a grenade came sailing from the bushes. I dived to the ground but fragments of the grenade bit me in the neck and in the right leg. That was too much. I was mad. I went into the bushes to get at the Japs, but there was no one in sight.

Corporal Floyd W. Gandee of Lorain, Ohio: The night was dark and rainy. I was on perimeter guard in my foxhole. There was about a foot of water in the hole. Nearby was a stream. Suddenly a booby trap we’d set along the stream snapped and exploded. I heaved six grenades in that general direction. Except for the flashes I could see nothing. I followed up the grenades with B.A.R. fire. Then a Jap yelled: “American stop shooting, we’ve enough, we’re leaving.” I yelled back, “Stop shooting hell.” The rest of the night was peaceful. Next morning I found that I’d killed a Jap lieutenant. He lay about three paces from my foxhole.

April 29 brought slow, hard going on the long road to Davao. Hundreds of buried mines continued to hinder the advance. Logical by-pass routes around burning bridges, too, were heavily mined. The roadside thickets were infested with snipers. Sharp fire fights developed at two Japanese road blocks. The Japanese had felled large trees across the road, mined the trees and emplaced machine guns to cover the block. The Nineteenth Regiment continued to spearhead the drive on Davao. The Thirty-Fourth Regiment weathered a night Banzai attack. Numerous ambushes erupted many miles behind the front. That day a score of Americans were killed or wounded.

“Look, fellows, this one’s a dud,” said Corporal Roger Manz of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He held up a Jap mortar shell that had landed in his foxhole that morning.

After a careful inspection he tossed the shell out of his hole. There was an instant explosion. Manz was stunned and half buried. Slowly he raised himself to his hands and knees.

“Somebody’s got to be wrong once in a while,” he muttered.

Private First Class Lawrence Zigler of Lansing, Michigan, accompanied a combat patrol as its radio operator. The patrol came upon a nest of trenches and there was a fight. The enemy was routed in a bayonet assault and finally fled toward a nearby river. The patrol pushed forward and collided with a sudden Japanese counter-attack. In the fight the patrol was pressed against the river. Standing at the edge of the gurgling stream, his forty-five- pound radio on his back, Zigler killed a pursuing Jap with shots from his pistol. Then Zigler tumbled into the river.

The river flowed swiftly and was shoulder deep. Zigler lost his foothold and was swept downstream. He thought of discarding the radio on his back but he held on. It was the patrol’s only means of communication.

The current smashed Zigler against a jutting rock. He grasped a ledge and clung. He watched a platoon of Japanese prowl past him along the river’s edge. The Japs did not see him. After they had passed, the radio man managed to scale the bank. He found his radio waterlogged and not functioning.

The patrol set up an emergency perimeter. In the center of the perimeter sat Lawrence Zigler, disassembling, drying and cleaning the parts of his radio, then putting them together again. The job completed, he was astonished to hear that the patrol had beaten off Jap skirmishers while he had worked, oblivious of the firing.

A 500-pound airplane bomb was set off by a lurking Japanese as a patrol passed the spot. Six Americans died in the blast. Six others were wounded.

A group of battalion runners surprised twelve Japanese fleeing northward on bicycles. When bullets snarled the Japs abandoned their mounts and scurried into an abaca field. The battalion messengers walked no longer. They sped their errands on bicycles made in Nippon.

Firing broke out in the night somewhere between two American battalions commanded by Major Roy W. Marcy of Walla Walla, Washington, and Major Nicolas Sloan of Hoopeston, Illinois. A thousand yards between them, both listened to the firing.

“Marcy’s catching it,” reasoned Sloan.

“Sloan’s catching it,” reasoned Marcy.

Then they checked by radio.

“No bullets this way,” said Major Sloan.

“None here, either,” said Major Marcy.

It was a brawl between two Jap raiding parties colliding in the night.

On May 1 the Division’s assault teams slugged to the gates of Davao. Mines and wrecked bridges had stopped all motorized advance. From the mountains around Davao Japanese artillery opened in a thunderous bombardment. It was later established that — gun for gun — hostile artillery around Davao outnumbered the Division’s field artillery three to one.

Eight hundred riflemen of the Nineteenth Infantry pushed up the slopes of Hill 550, a dominating height overlooking the coastal road and the city of Davao. The hill was desperately defended from scores of pillboxes, caves and tunnels. Seventeen days of murderous cave-and-tunnel fighting went by before the height could be secured.

The Division’s field artillery ground forward. Its guns roared all through the hot afternoon. Cub planes ranged ahead for observation. Mortar, machine gun and rifle fire met the Americans’ advance along three coastal roads. Japanese detachments attacked a motor park and a bridge repair party along the Division’s 130 mile long route of supply. The Division vanguard captured an enemy bivouac. There were large stores of lumber, engineering equipment, automobiles, bulldozers and tractors and much artillery ammunition.

A lone Japanese crawled into an artillery perimeter and tossed a box full of dynamite into the cannoneers’ kitchen. In the hills southwest of Davao “King” Company of the Thirty-Fourth Regiment seized ten Japanese machine guns. Its scouts reported that a maze of hidden emplacements covered all hillsides like spider nests. The unavoidable test was at hand. In number the Japs were stronger.

With nightfall the Division’s assault elements stood poised on the banks of the Davao River. Cannon fire grumbled in the hills. Nippon’s capital in the Philippines lay dark and silent. Peering across the river that night, Colonel Clifford quietly announced: ‘Tomorrow we storm Davao.”