Editor’s note: The following comprises Chapter 18 of Children of Yesterday, by Jan Valtin (published 1946).

(Continued from Chapter 17: Island Raiders)

_____________________________________________________________________________

“ZigZag Pass was not lightly named. There is no to show but half the twists and circles, the dips rises, the strong slopes, the cliffs and gorges that make it hazardous and difficult fighting ground. Each turn masked the road beyond. Having passed one turn, the road was visible only to the next.

“The Jap was getting rough….”

(from the Historical Record of the Thirty-Fourth Infantry Regiment)

_____________________________________________________________________________

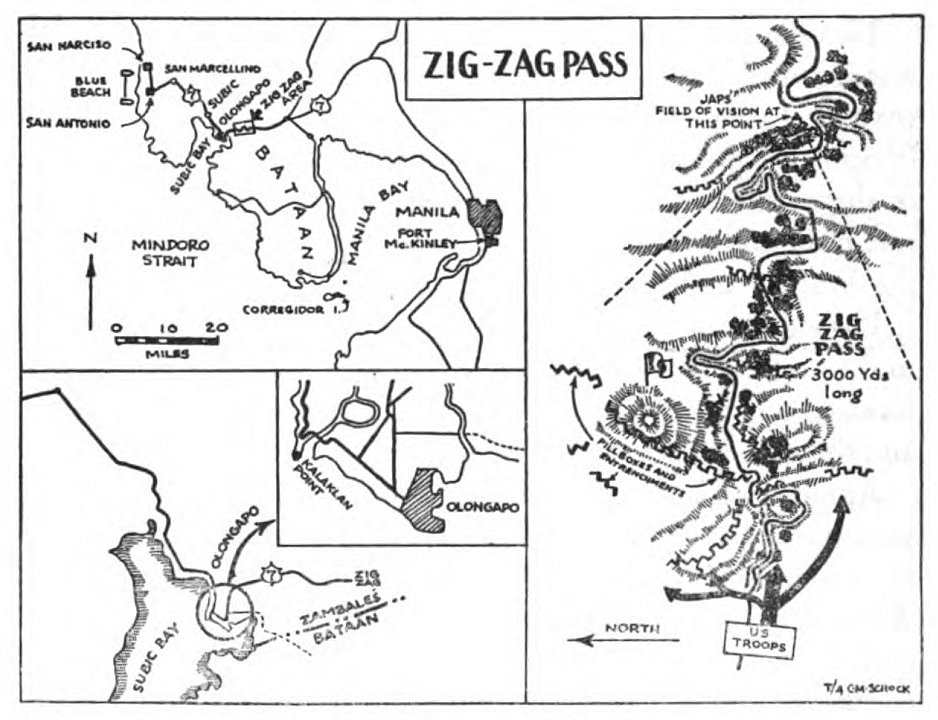

Eight years before the Japanese stole the Philippines, an American major surveying Zig-Zag Pass, Luzon, voiced the opinion that “a small force taking advantage of the natural defenses could hold Zig-Zag Pass against any size force until hell freezes over.” But now the Japs held the pass. They held it with thousands of first line troops, and they had had three years in which to dig their defenses.

While other elements of the Division scoured Mindoro, the Thirty-Fourth Regimental Combat Team fought with a task force[1] ordered to seal off Bataan, to deny this natural stronghold to Jap forces driven southward by MacArthur’s invasion of Lingayen Gulf. From the town of Olongapo on Subic Bay a highway winds eastward to Manila. This is Highway 7. Where Highway 7 crosses the base of Bataan Peninsula, it twists upward through a mountain pass, a nightmare of hairpin turns and sight-blocking spirals: Zig-Zag Pass, the mission’s key objective.

Two hours before dawn, on January 29, 1945, the convoy of war-spawned ships anchored seven thousand yards off the west coast of Luzon. Phlegmatic mine sweepers cleared the waters fronting the invasion beaches. Helmeted men crowding the decks of ships studied the shore. Low tide was at 7:09 A.M. The sun rose clear and brassy at 7:30. The sea was calm, the surf light, the beaches undefended.

Beyond the beaches the mouth of a valley rose into a saddle to the east. South of the valley mountains loomed. Field glasses revealed a twisting road cut into the promontories of Subic Bay, and the wreckage of blasted bridges.

Around the larger ships the swarm of assault boats drew nervous wakes in the cobalt. Destroyers hovered offshore, watching for the geysers in the sea that would mean the beginning of battle. Aboard the transports, ward rooms were transformed into surgeries. Doctors stood idly watching, waiting, their clean hands in the pockets of their clean smocks. A canoe bearing three natives passed the bow of a destroyer. It hoisted sail and made for shore. Someone on the bridge bawled a query about the canoe. Nobody did anything about it

Through the loudspeakers a calm voice said: “The surf is low. The landing is dry. The first waves have gone ashore. They are moving in standing up. They were met by natives waving American flags.”

There were no Japs on “Blue” Beach, where the assault teams of the Thirty-Fourth struck. Ashore, gaunt in the midst of a riotous native crowd, stood a bearded man in tattered khakis. He was armed with an ancient .45 pistol. He held an old straw hat in his hand and said nothing. His eyes were somber, and shining with tears. He was Captain Joseph Craine, United States Army. For three years he had made single-handed war against the Japa nese in the mountains of Zambales Province. Each night in prayer he had reaffirmed his faith that some day American troops would come back to Luzon.

Now they were here.

A battalion commanded by Major Harry L. Snavely of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, spearheaded the drive into Bataan. It was found that trucks could not be landed on Blue Beach.[2] So Snavely led his men in a forced foot march through southern Zambales. The day was dry and hot. The sun-baked roads followed long-dried stream beds. The vanguard passed the village of San Antonio and struck Highway 7, which had a solid crown. Though many sagged from heat exhaustion, Snavely’s infantrymen traversed San Marcelino and Castillejos. They pitched bivouac at dusk without having met a Jap. In seven hours, loaded down with weapons and equipment as they were, they had slogged forward seventeen miles.

Hard on the heels of the vanguard battalion toiled communication parties under Lieutenant Anthony Roozen of Mankato, Minnesota. On this day, and throughout the campaign, their telephone wires followed the attack teams as a tail follows the dog.

At the same time a lone sergeant mobilized a swarm of natives to establish an ammunition dump on Blue Beach. When the trucks arrived, the sergeant had them loaded, and then he guided his ammunition convoy to the spearhead battalion. After that he returned to the beach and moved the remainder of his dump sixteen miles to Castillejos. It was an uninterrupted 48-hour grind. Yet, the sergeant stood guard over his ammunition stores all through the following night. “It was a matter of conscience,” he said. His name: George Shattuck, from Minneapolis.

The goal for January 30 was the town of Olongapo at the approaches of Zig-Zag Pass. Guerilla guides reported for duty before dawn. Patrols found bridges along the highway burning. The assault teams ate a K-ration breakfast in starlit darkness. The ad ance continued at 8 A.M.

Between the advance battalion’s bivouac and Olongapo lay the village of Subic.

But where were the Japs?

On the previous day Filipinos had reported the presence of strong Japanese detachments in Subic. The spearhead entered Subic at 9 A.M. There was a tomb-like silence among the unpainted huts and buildings. Rust covered the corrugated iron roofs. The battalion searched every house. Subic was empty of life.

The march on Olongapo continued at 11 A.M. The bridges across the Matain and Matagan Rivers were still afire. Infantrymen forded the streams, wary of ambush.

At the next river — the Kalaklan — the Japs were ready.

They had chosen their position well. They had fortified a cemetery which overlooked the highway. A pillbox commanded the Kalaklan River bridge. On the other side of the road, around the lighthouse of Kalaklan Point, they had dug machine gun bunkers and trenches. Cliffs dropped from the road shoulder to the sea. Guns on the lighthouse promontory covered the cliff sides. At low tide a narrow strip of sand skirted the base of the cliffs.

“Item” Company led the assault. One platoon ascended the hillside and approached the cemetery in a bear crawl. Another platoon muscled down the cliffs and toward the lighthouse bastion. A third group advanced toward the bridge.

A solitary Japanese crept onto the bridge from its southern end. His mission, apparently, was demolition. From eight hundred yards away the muzzle of a Garand traced his movement. Steady behind the Garand’s sights peered the eye of a Yankee sergeant. The Garand barked. The Jap dropped in his tracks. The sergeant fired again to make sure.

That opened the battle for Bataan. From among the graves machine guns spat. Gunfire rattled from the rocks of Kalaklan Point. The pillbox at the bridge belched steel. The platoons attacked in a concert of fire and movement. Men were hit, staggered to their knees, then sprawled. The attack did not halt.

The cemetery was quickly taken. Bullets chipped fragments from tombstones. A scout fell wounded across a grave. From other graves Japs fired at the fallen scout. Sergeant Walter Orzepowski of Bayonne, New Jersey, turned his Garand on the snipers. As they dodged away behind the monuments, Orzepowski rushed forward and pulled his scout to cover.

Tank-destroyers ground forward. They blasted the pillbox at the end of the bridge. Then they turned on the lighthouse bastion, where resistance was stubborn. Logs, rocks, dirt flew into the air, and with them the wreckage of a machine gun and its gunners.. Riflemen closed in.

Private John Deeghan of Renova, Pennsylvania, rushed an enemy emplacement, shooting as he ran. He followed up with a grenade, then with grit and muscle. He killed one Jap, wounded two, and two others scurried down the cliffs. Rifle bullets sent them tumbling into the sea.

A machine gun burst caught a scout through the hip. He floundered on the rocks, in view of the remaining Japs. Sergeant Roger Guilliam of Defiance, Ohio, and Private Victor Hinze of Racine, Wisconsin, hurried to his aid. Machine gun and rifle bullets struck sparks from the rocks about them. Lying flat on their bellies they bandaged the injured scout, and the only words said were, “Now… roll him over… gently, gently…”

To the rescue of another wounded soldier sprang Private William Rose of Connersville, Indiana. Bullets twanged in front of his feet, pinned him down. Rose lay on the rocks, his hands stretched toward his helpless comrade. “Andy,” he shouted, “Andy, I’m coming.” The battle-injured soldier did not answer. Bill Rose jumped up to hasten to his side. Jap bullets ripped their lives away.

Black smoke climbed over the hills. The Japanese had put the torch to Olongapo. Engineers removed dynamite charges from the Kalaklan River bridge. Booby traps and land mines infested the Olongapo road. The town was gutted. The Japanese destroyed everything that could be of use to the task force. American artillery destroyed everything that could be of use to the Japs.

The vanguard battalion moved through the burning town. Once an American naval base, it had become a corpse. There was an old-type Yankee helmet lying in a garbage-littered yard. There was a German-made diesel generator in the shower room of a demolished tennis club. There were the old Spanish towers, crumbling and black. The Japs had converted them into a prison full of dirty, tiny, suffocating cells. And there was also Kiochiro Kusumi, an aged Japanese, who had once been a cook for a unit of United States Marines. He had lived in the hills for many months, a fugitive from his compatriots.

“I lived in Olongapo thirty years,” he said. “I no like de Japs.”

Olongapo smoldered for many days.

On January 31, the riflemen secured the approaches to Zig-Zag Pass. “Able” Company set out to block the junction of a lesser road with Highway 7 in the rear of enemy outpost positions.

Where the highway crossed looping reaches of the Kalaklan River, two bridges had been demolished. Engineers had built emergency bridges during the night, and bulldozers had scooped out fords for the heavier traffic and paved them with gravel taken from an old railroad bed. Some distance to the east the Japanese provided illumination for the engineers by setting fire to an oil dump. The enemy attempted to disturb the construction. Guards opened fire in the darkness.

The mountains through which Zig-Zag Pass is cut rise abruptly from the Olongapo Valley. A roaring vegetation flanks the road and the river. A narrow gauge railway has been hewn out of the rocky slope above the road. To the south high ground ended in a twin-peaked ridge.

One “Able” Company force seized the twin-peaked ridge. An other moved forward astride Highway 7. The assault teams found well-built fortifications — unoccupied by Japs. But from high grass along the abandoned railroad bed to the right of the road lanced rifle fire, machine gun sprays and grenades. An officer and a soldier of the advance party collapsed. The others hurried off the road and into cover.

Counter fire was ineffective. The Japs were entrenched in strength, on high terrain, but not a Jap could be seen. The vanguard fell back. Phosphorus shells lobbed from American mortars set the grass along the railroad bed afire.

“Able” Company’s commander decided to by-pass the resistance. Scouts found a trail which circled the twin-peaked hill. The company swung around the enemy block, forded the 300- foot-wide Kalaklan River and seized its objective, the road junction. On its way it passed two Japanese machine gun installations unobserved. The enemy gunners were watching the highway to Manila…

A patrol set out to explore the surrounding terrain. It skirted a ravine, unaware that the ravine was alive with Japanese. The Japs allowed the leading scout to pass. They raked the body of the patrol with mortar shells and machine guns. Simultaneously a sniper shot at the scout.

The scout was Private Ben Guzman of Centerville, California. The first bullet pierced his leg. Guzman rolled behind a tree. He tried to locate the sniper. Underbrush obscured his view. He crawled away from the tree toward another tree which stood on higher ground. Again the sniper’s rifle cracked. Ben Guzman was shot through the shoulder. He was faint from loss of blood, but he was furious. Also, he knew that if he remained where he was the sniper would shoot him again.

He could hear two Japs shouting to one another in the thickets. Ben Guzman crawled to a third tree, still searching for his sniper. He could not see him. But again the sniper’s rifle cracked. Guzman winced. A third bullet had hit him; in the leg, inches from the first. He groaned with pain and frustration. Then he heard the sniper laugh.

The laughter came from a clump of grass on a small rise twelve yards away. Ben Guzman rolled into a bush. He dragged himself forward on one hand and one knee and circled the sniper. He reached the fringe of the clump of grass. He tossed a grenade. He sprang to his feet, lurched toward the Jap. The sniper was stunned from the concussion. Guzman pumped him full of bullets — and collapsed atop his dead assailant.

Across the highway three soldiers advanced to rescue their scout. They tangled with other snipers in the thickets. They found Ben Guzman and guarded him until a corpsman could arrive.

“Able” Company’s road block held. Infantry battalions and tank platoons passed through on their way to Zig-Zag Pass. Long stretches of Highway 7 were now under continuous enemy machine gun and mortar fire. The sparring was at an end. The foe gave battle.

While “Able” held the road, “Easy” Company occupied Olongapo Harbor. “King” and “Love” Companies crossed the harbor slough to seize a promontory named Maritan Point. They came to a river mouth too deep to be forded. The riflemen commandeered all native canoes in the neighborhood and crossed the river. ‘Love” Company — in the style of the Indian wars — attacked Maritan Point in a fleet of canoes.

Anti-Tank Company teams dug mines from the captured portions of the Manila Highway. Cannon Company defended Subic Bay. Guerilla detachments roamed on spying missions. Neil Wood, from Bogalusa, Louisiana, and Frank Weeks, from Oklahoma City, led carrier trains with food, water and ammunition to the front lines. Though half the men in their parties succumbed to heat fatigue, they again and again hiked through the firing zones to consummate their job. On their return trips they transported the wounded and the dead.

By the end of the day the American command knew that there were some 5,000 Japanese in Zig-Zag Pass. The Japs were malaria-ridden, but well equipped. They had plenty of artillery and their morale was high…

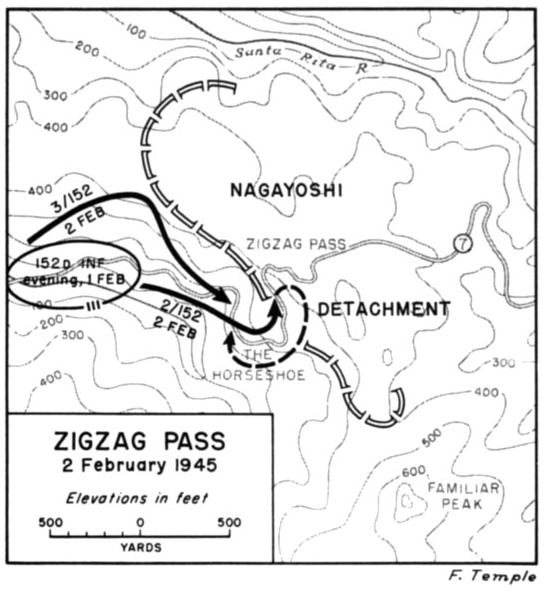

The regiments of the 38th Infantry Division pounded into the maw of Zig-Zag pass.[3] The tide of battle surged uncertainly up and down the savage slopes. Ambulances churned in relays between the field hospitals and the front. Truckloads of dead rolled back for military burial. The Thirty-Fourth Regiment, meanwhile, was held in reserve.

To be “in reserve” does not mean to be at rest. During the night of February 1, enemy artillery shells struck the perimeters. There was intermittent sniping on all positions.

Two Japs approached Kalaklan River bridge in a canoe full of explosives. Guards killed one. The other jumped into the river and disappeared.

In the dead of night a suicide detail of four Japs rushed into the “Baker” Company bivouac and hurled explosives. Three escaped in the confusion. One was shot to death.

Again, at noon, February 1, a mountain outpost encountered a lone Jap armed only with a knife. The Jap insisted on storming the outpost. He was killed.

At Maritan Point “Love” Company’s riflemen boarded their canoes and adventured down the coast. They found a camouflaged radio station operated by a grinning guerilla. He informed the Americans that native patriots had cut off the heads of the Japanese garrison. The Americans were satisfied; more so when they heard that their random excursion had made them the first American troops to return to the peninsula of Bataan.

New orders arrived in the small hours of February 3: the regiment was to relieve the 38th Division in the storming of the Pass.

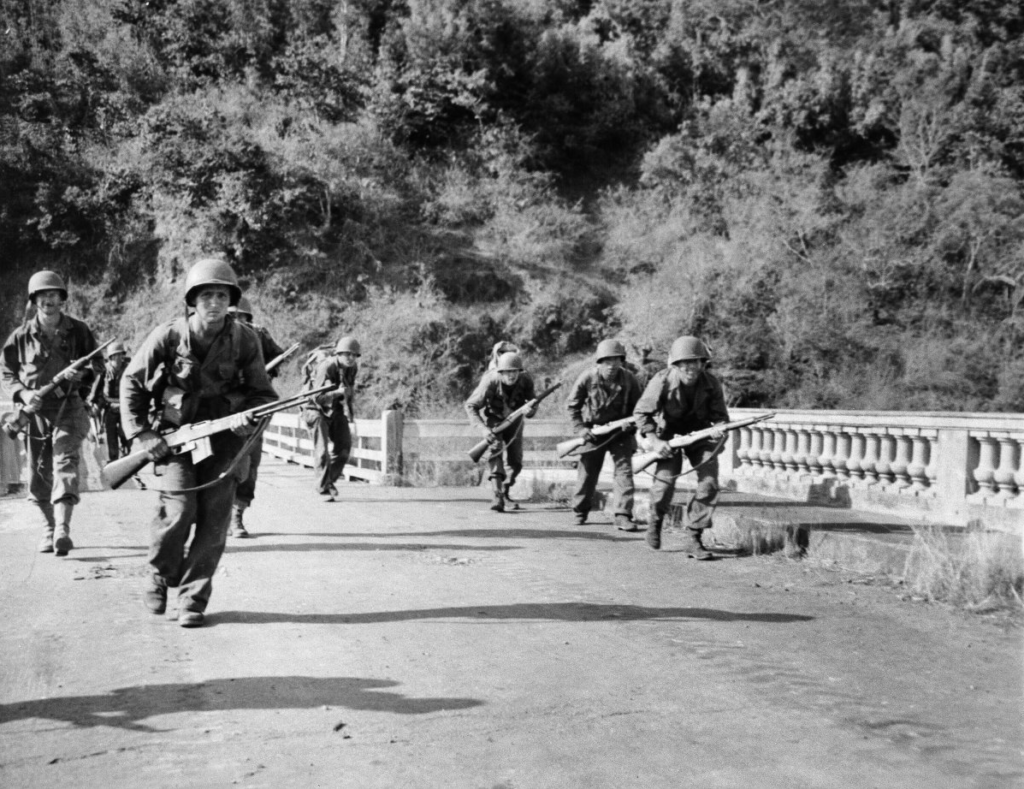

The regiment advanced into Zig-Zag Pass in a column of battalions. They crossed the Santa Rita River. They passed wooded mountainsides and remnants of abandoned logging camps. Zig-Zag Pass swung south in a great loop. This “mother” loop was sinuous with eleven minor loops, each of which changed the direction of Highway 7. Each loop of the road provided the Japs with an almost perfect defensive position. On the left a hill mass towered over the highway in five nearly perpendicular noses. On the right the ground careened into deep gullies. The heights and the precipices were covered with jungle. Toward the end of the “mother” loop, Highway 7 dropped down a sweeping gorge. Jap strong points burrowed deep into the heights commanded every yard of the way.

At 10 A.M., “Baker” Company, striking across jungle between two loops of the road, radioed that it had entered a zone of hostile mortar fire. Japanese machine guns firing from natural bulwarks stemmed the advance. Lieutenant Tom Rhem, the company commander, was shot through the hip, but remained to direct his troops in the fight until nightfall.

Other companies reported hostile artillery concentrations. The whole American end of Zig-Zag Pass was rocked by the explosions. There had been no warning, no sensing to find the range. The enemy field guns were zeroed on the loops. The bursts were sudden and accurate. Trucks were destroyed by direct hits.

The advance stopped. Counter-batteries thundered.

The vanguard companies left the highway in an attempt to circle the impact zone of the barrage. “Charlie” Company climbed over one of the “noses” and knifed into enemy entrenchments on the slope beyond. Its first thrust was repulsed by interlocking bands of machine gun fire. Some wounded men were left lying between the Jap holes. Private Bernard Schneller, from Carlton, Oregon, moved up and down the killing line and helped away the wounded. In his platoon every third soldier had been hit. Sergeant George Parsons from Charleston, West Virginia, stayed inside the Japanese lines to guard the wounded who could not be carried out.

Jap gunners in a pillbox had singled out Parsons as their target. Parsons’ alternatives were to run for his life, or to lose it staying with the wounded. He stayed — and lived. To the rescue came Private Ed Gonzales, who called the deserts of New Mexico his home.

Gonzales rushed the pillbox. He fired his submachine gun through the ports of the pillbox until a Jap bullet brought him down.

“Baker” Company cut through rain forests parallel to Highway 7, driving Jap defenders from the roadbed. “Able” Company thrust in a wide flanking movement to the east. They worked through jungle and over mountains, guided by compass. The terrain was confusing. Once a man was more than a few feet away from the road, orientation became a matter of guess. “Able” Company circled cliff s and ravines, and was thrown off its course. Its only contact with the battalion was by a field radio in the hands of Private Zeno Reitmeyer of Madison, Wisconsin. The company remained isolated and surrounded by Japanese for two days. Radioman Reitmeyer was on duty every hour of that time. Meanwhile, on the battle maps, the location of “Able” Company was marked, “Unknown.”

By 4 P.M., both “Baker” and “Charlie” teams were locked in a bitter fire fight. Of the enemy little or nothing could be seen. He fired from caves and tunnels and shrub-masked holes. His artillery thundered from positions more than a thousand yards beyond the far side of the “mother” loop on Zig-Zag Pass.

The Japs had mined Highway 7. The mines were buried in the roadbed. Detonating wires led through underground pipes from the mines to foxholes in the adjoining jungle. Japs waited in the foxholes. At other places the Japanese had felled trees across the road, augmented by nests of dynamite designed to blow up anyone attempting to remove the obstacles. At 5 P.M., guerillas reported that a force of one thousand Japanese reinforcements was moving in over a woodland path known as Telegraph Trail. The attack was stalled. All companies dug in at dusk and held on. Night brought on a counter attack, and over Zig-Zag Pass artillery dueled until dawn.

On the morning of February 4, “Able” Company radioed that it was beleaguered on a mountain slope (“Familiar Peak”) and unable to fight out of the trap.

At 10 A.M., in the wake of a rolling artillery barrage, the battalions resumed their winding, uphill push on Highway 7. “Easy” Company was the vanguard. It rounded a “2″-shaped curve and met machine gun fire. The company was pinned down. To its right, “Baker” Company was also nailed to the ground. Both tried maneuvering to the flanks. But each movement they made drew fire from a different direction. There was intensive sniping from a gully in “Easy” Company’s rear. The terrain was so narrow and the curves so sharp that the following battalions could not deploy to fight. One team of riflemen endeavored to rout the snipers from the gully. It was repulsed by bullets from other snipers lurking on higher ground. The vanguard radioed for shell fire.

The cannoneers worked with precision. The first round landed on the road a few feet beyond the Jap position. Another blasted snipers from a knoll. Then another squarely hit a hostile machine gun emplacement. The shells whistled hazardously close to the treetops under which “Easy” Company held its line.

A colonel and his liaison party were taking cover in a ditch on the left side of the highway. At this moment an artillery shell aimed at the Japanese two hundred yards in front caught a branch of a nearby tree. Seconds of silence followed the shattering roar.

Then there were screams. The colonel raised his head from the dust and quietly remarked, “I got it.”

Major Harry Snavely, battalion commander, led “Fox” and “George” Companies in an enveloping movement to knock out hostile strongpoints from the rear. But again there blazed well-aimed fire from all directions.

At this time, “Charlie” Company made slow but steady progress on the southern flank of the road. The battalion commander slogged with the advance elements. Suddenly rifle fire crackled from ground slightly higher, not many yards away. “Don’t fire, these are our troops,” the commander shouted. Scarcely had he spoken when a grenade thrown at him exploded beside his head. His face was lacerated, his arms and chest pierced in many places.

By the road, twenty minutes to the rear, sat the crews of several tanks, waiting for a mission. The tanks were called forward. At 4 P.M., they assaulted the strongpoints blocking Highway 7. The leading tank lumbered around a bend and sprayed the hillside with machine gun slugs. But the Japs refused to fire on the tank. They fired on the riflemen beyond. Searching through his periscope the tank commander was unable to spot the enemy position. A tank “buttoned down” for battle has only a small field of vision. The tank commander selected a promising knoll, swung his turret into line, and dispatched a 75 millimeter shell. It was a true hit. A hidden pillbox blew up in death and ruin.

It was as if the tank’s gun had been a match held to an immense reservoir of TNT. Out of the blue sky an avalanche of mortar and artillery shells descended on the American troops in Zig-Zag Pass.

Gun after gun spat steel and high explosive with resolute accuracy all along the curving road — and into every position American troops held or had held during the day. The barrage continued far into the night. The Japanese were not guessing. They knew.

Under the blightening horror of the barrage the assault team gave way. The many dead on the highway were torn to bits by a succession of explosions. The wounded lay writhing with jagged holes in their chests or bellies, with an arm or leg shattered, or with broken bones. The day’s thousand-yard advance was made for naught

Nearest to the Japanese position lay a squad of riflemen under the command of a private, Jack Davies from White Plains, New York. The squad leader had been hit and Davies had taken over. In the agonized withdrawal he kept his squad in line and fighting until the last cartridge on hand had gone its way.

In another unit Sergeant Eric Erickson of Blairstown, New Jersey, saw his platoon leader and two aides blown to pieces in the hellish descent. Half of the other men in the platoon were wounded. Erickson grasped command of the demoralized platoon. He organized the fit survivors into litter teams and quietly covered the evacuation of the dying and the wounded.

Private Harry Potter, a scout, remained calm when panic seized his group. He had spotted a nest of Japs. He killed one and continued to fire at the others until his gun jammed in his hands.

Sergeant Layton Ernst of Eyota, Minnesota, lugged smashed-up mortarmen to safety.

Sergeant Edward Benik of Moquah, Wisconsin, saw six members of his machine gun section cut down by fragments. He put the survivors to fashioning litters from rifles and ponchos and led the transport of the wounded to the rear.

“Fox” Company, on a roadside hilltop, was dispersed by the barrage. The men fell back wildly, alone or in scattered groups. But four riflemen remained on the hilltop through the night to guard the wounded. (Their names are on their regiment’s honor roll for all time to come: Sergeant Jere Kuehn of Parkdale, Arkansas; Private First Class Howard Herman of Seattle, Washington; Private First Class Mariano Chavez of Los Lunas, New Mexico; and Private First Class John Lynch of Clarksburg, West Virginia.)

Driving a six-wheel truck loaded with rations was Private Lome E. Curtis, from Eldred, Pennsylvania. He had left Olongapo at 4 P.M. and he was driving toward Zig-Zag Pass. Except for a scattering of snipers the road seemed clear. Curtis eased his truck around mines, shell holes, fallen trees and occasional corpses, and everything was fine. Suddenly there was a snarl in the air, followed by an explosion and a cloud of black smoke on the road ahead. More shells followed the first. Curtis maneuvered the truck into a ditch. He jumped out of the truck and ducked in the ditch.

But Lorne Curtis was bothered by the knowledge that his comrades up front had not eaten since early morning. It was his mission to bring them their rations. He climbed out of the ditch and back into his truck. He started the motor. He whispered a prayer and then he eased in the clutch. His truck rumbled on through the artillery barrage.

He reached the furthermost battalion command post and delivered his two tons of rations. The thunder of bursting shells was near and continuous. Curtis heard the whirr of fragments crashing through vegetation. The battalion adjutant leaned over and shouted into the truck driver’s ear.

“Up front the wounded are piling up. We can’t get them out by hand.”

Curtis dumped the rations from his truck and headed to the firing lines. He backed his truck through a series of mines and then he had to stop because the road was littered with bleeding men. He loaded sixteen wounded soldiers into the truck and drove back down the blasted road to Olongapo where a field hospital had been established.

At the 18th Portable Field Hospital the wounded arrived in loads. The trucks and jeeps and ambulances dripped blood. Six doctors, on the verge of exhaustion, toiled like titans through forty-eight hours. Shells make uglier wounds than bullets. Captain Alan Tigert patched up one man whose heart pulsed uncovered in his split-open chest. And out at the half-abandoned front, under shellfire, in a caldron of dirt and sweat and noise and tattered flesh, toiled the battalion surgeon, Captain George E. Morrissey of Davenport, Iowa; hands steady, and a strangle hold upon his jangled nerves.

The punished remnants dug in for the night. Men drugged with fatigue cleaned their weapons. Here and there a rifle blurted into the gloom beneath the stars. Sleep was fitful; wakefulness poisoned with bleak fear.

A field report sent back at dawn, said, “No activity, night of February 4-5.”

The cooks were awake and at work before sunrise February 5. They lit their field stoves in defiance of snipers. At dawn the men of the assault teams rolled out of their foxholes. They shook themselves awake and mopped faces and necks with a few ounces of water from their canteens and cursed the war and the Philippines. They drank hot coffee and ate a fat mess of dehydrated eggs; after that they were ready.

Their advance crossed bitterly familiar ground.

The Third Battalion pushed to the ridge from which they had been driven the previous day by the barrage. Patrols forged to the crest. In the final climb the scouts pulled themselves up with the aid of roots and vines. Japs held the crest. They opened fire at a range of ten feet and chased the spearhead back to the lower slope. Then flame throwers and bazookas were brought into play. Documents taken from enemy dead identified them as members of the Osaka Infantry Regiment.

Offensive movement was resumed on Highway 7. The Thirty Fourth Regiment held the center. Other elements of the task force advanced to the right and left of the road. They rounded a bend and the shoulder of a mountain. The sun hurled flamboyant javelins. Japanese mortar shells plummeted from the brassy sky.

On the roadside a company commander and two sergeants discussed a shortage of equipment. A mortar burst ended the discussion. There was a flash, a roar, and blood tinting the dust. The company commander was critically hurt. The supply sergeant, Leo Heck of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, was hit in his left arm and in both legs. The second sergeant, Lewis Downey of Muskegon, Michigan, had gone off to pee and was unhurt. Downey carried his fallen commander to the rear, followed by Heck who dragged himself through the dust.

By 9:30 that morning the dragon of Nippon again whipped his tail in fury. He caught the Yankee Dragon Regiment squarely in the face. It was pinpointed, unendurably concentrated artillery fire. It was machine gun fire from the flanks and sniper fire from the rear.

Friendly field artillery replied. Shells from both directions cut the morning air to ribbons. “Charlie” Company’s commander was wounded for the second time in two days. His first sergeant was knocked senseless by concussion. Fifty men and all officers but one were killed or wounded. Riflemen clawed into the hard earth of Zig-Zag Pass. Major Snavely, reorganizing his command, urged them to hold on.

Joseph O’Malley, a mortarman from Newark, New Jersey, had a bead on a Jap machine gun. He mounted his mortar in a shallow shell hole and silenced the gun. There were friendly machine guns hammering nearby, and the hammering suddenly ceased. O’Malley discovered that every member of the friendly gun squad had been hit by shrapnel. “Hey Joe,” he said, “take over.” He turned his mortar over to his assistant gunner. He crawled across the road to the silenced machine gun emplacement. He rolled the disabled machine gunners into the shelter of a shell hole and then he manned the machine gun himself. The gun hammered until another Jap shell blew O’Malley into the road.

Direct artillery hits roared into a ravine where a detachment had taken cover. The ravine echoed the cries of the dying. Technician Dallas Johnson of Windom, Minnesota, had his knee smashed by shrapnel. A few feet away a corpsman was working over a soldier who was hurt worse; compound fractures. Johnson cursed his knee and crept over to help the corpsman carry the other wounded to an ambulance on the road.

Amidst the desolation of high explosive and shattered lives Chaplain James J. Moran, from Shaker Heights, Ohio, administered the last rites to the dead. In the enormous thunder of the detonations his voice was austere and calm. “O Lord, let Thy mercy be upon us: As our trust is in Thee… Hear my prayer. O Lord…”

With a solemn “Rest in peace, comrades” he turned away. And then James Moran laid hand on the litters and helped to transport wounded men to ambulances on the road.

A little way off another battalion chaplain, Captain Kingsley W. Hawthorne of Belmont, Massachusetts, spat into his hands and pitched in. In the hard clamor of mortar and machine gun fire he took command of the evacuation of casualties. He directed men in the task of dressing wounds. He administered morphine to men screaming with pain. He gave sulfa, he carried litters, he spoke words soothing and confident and firm. He did not leave the death-raked highway until the last of the wounded had been carried to shelter.

Toward noon a flight of high explosive shells howled over the hills and landed in the center of a battalion command post. The shells struck the trunks of trees directly over the foxholes. The sergeant major, the operations sergeant, staff officers, radiomen, telephones, battle maps and weapons flew to the four winds.

Threading a course through shell craters and wreckage was a jeep and a trailer driven by Private James McFee of Parkersburg, West Virginia. Jeep and trailer were loaded with mortar ammunition. McFee saw the wounded covering the roadside. He stopped. Around him shells whined and burst. McFee jumped from the jeep and helped the fallen. But abruptly he was in the grip of an awful fear; what if a shell should strike his jeep and trailer? The ammunition would blow sky-high. More men would die in the explosion. He sprang back into the jeep. The jeep was parked in a deep rut. McFee coaxed and worked for ten minutes before he extricated it from the trap. Then he drove out of the shelling. Minutes later a 90 millimeter mortar shell burst where jeep and trailer had been…

At the height of the artillery slaughter there was such a shortage of aid men that Sergeant Ernest Dillingham, from Elmore City, Oklahoma, hastening from hole to hole, pressed riflemen into service as corpsmen. When medical supplies were exhausted he led a party to the destroyed command post to look for more. The earth in front of him erupted. Ernest Dillingham sagged to his knees. Both hands clutched his abdomen.

It was as if the mountains of Bataan reveled in brutal laughter at the Americans’ plight. The Jap cannoneers did not have to test the range. There was neither bracketing nor registration. Their shells sped straight to the target, multiple bolts from the blue. There was no room for evasion or maneuver. From their observation posts on the high mountains enemy observers had a perfect field of vision of every loop of Highway 7. They sat there “looking down the throats” of the men of the Thirty-Fourth, counting the rifles and trucks, watching and waiting for the Americans to enter prepared fields of fire, then cutting loose and watching what happened and correcting the errors and starting in somewhere else. Of the Japs and their mountain batteries nothing could be seen from the bottom of Zig-Zag Pass.

The battalions fell back and dug in again and the enemy barrage dogged their retreat and thundered over the perimeters all night. Men dug their foxholes deeper and huddled low. Calls for aid men were like whimpers in a hurricane.

Sergeant Leroy Johnson of Orange, Texas, went forward with a captured knee mortar and a sack full of shells to ward off a band of snipers.

Technician Kenneth Seitner of Dayton, Ohio, shouldered into the shell bursts to drag out the wounded. A shell found him. He died quickly.

An outpost on a ridge above the perimeter dissolved in a direct hit. A soldier came running downhill, terror on his face. His comrade up there, he said, was bleeding to death. Without a question or a second’s preparation a surgeon, John Kernodle of Durham, North Carolina, aided by two volunteers, crawled out into the murder night. They crawled three hundred yards up a black mountain trail overgrown with vegetation. They found the wounded sentinel and saved his life. They also found the ridge acrawl with snipers. They remained on the ridge until daylight. They lay on top of the ground because the sounds of digging would have signaled their location to the snipers.[4]

Dawn came.

A message sent by the commander of the Thirty-Fourth Regiment to higher headquarters read:

“I AM CONVINCED THAT THE JAP POSITION CANNOT BE CRACKED UNLESS THERE IS A WITHDRAWAL TO A POINT WHERE ENTIRE CORPS ARTILLERY AND ALL AVAILABLE AIR WORKS IT OVER WITH EVERY POSSIBLE MEANS FOR AT LEAST FORTY-EIGHT HOURS. MY FIRST AND SECOND BATTALIONS HAVE SUFFERED TERRIFIC CASUALTIES, AND IT IS BECOMING QUESTIONABLE HOW LONG THEY CAN HOLD UNDER THE POUNDING.”

The troops — and the pounding — both held. So did the wisdom of the recommendation.[5]

(Continue to Chapter 19: We Storm Corregidor)

________________________________________________

[1] This task force consisted of the 38th Infantry Division and the 34th Regiment of the 24th Infantry Division. Since this volume deals with the battle record of one infantry division, the narrative will be limited to the activities of the 14th Infantry Division teams in the battle for Zig-Zag Pass.

[2] Landing ships bearing trucks were detoured and finally landed their vehicles near San Miguel.

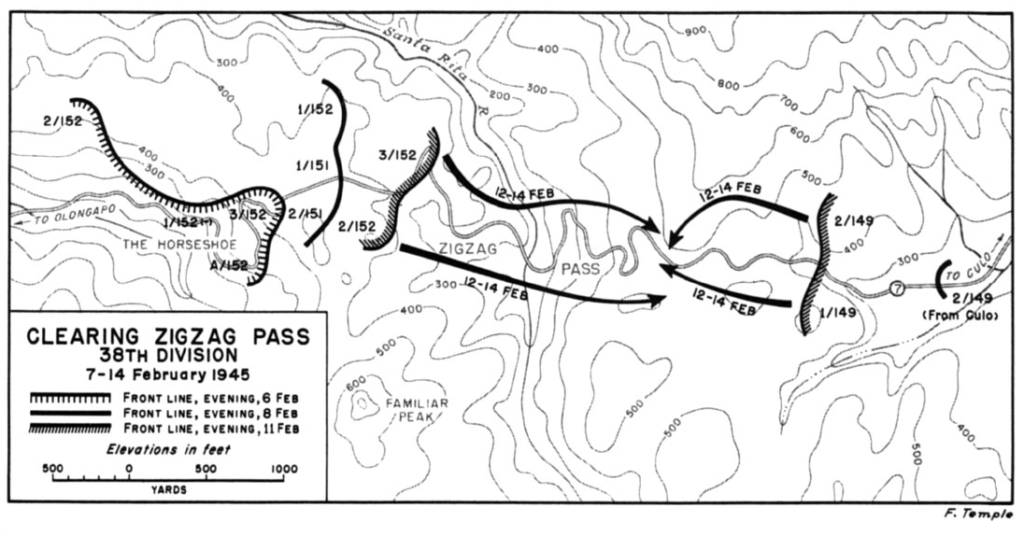

[3] The regiments of the 38th Infantry Division which made the initial, costly assaults on Zig-Zag Pass were the I5and and 149th Infantry Regiments.

[4] First Lieutenant John R. Kernodle’s helpers were Staff Sergeant Willard R. Harp of Durhamville, New York, and Technician James R. Carter of Ennenton, South Carolina.

[5] On February 6 the Thirty-Fourth Regiment was relieved on Zig-Zag Pass by the 151st Regiment of the 38th Infantry Division. On February 7, Japanese positions on Zig-Zag Pass were bombarded with 4,000 demolition bombs and 1,320 gallons of Napalm. The process was repeated on February 8th, 9th, and 10th. Zig-Zag Pass was then stormed by the regiments of the 38th Infantry Division. After fourteen days of fighting the whole length of Zig-Zag Pass was in American hands. Thus, Japanese armies fighting in the north were denied a retreat into Bataan Peninsula. Soon thereafter a message was received which read: “…JAPS WERE OBSERVED WITHDRAWING FROM BATAAN TO CORREGIDOR VIA SMALL NAVAL CRAFT.”