Editor’s note: The following comprises Chapter 16 of Children of Yesterday, by Jan Valtin (published 1946).

(Continued from Chapter 15: Dragon Red)

____________________________________________________________________________

“Most of this fighting is in inconspicuous little actions which nobody hears about — mopping up.

In Europe when we advance we really capture something. Out here we just capture another island, important though it may be, that looks much like all other islands. As one doughboy remarked after we had cleaned out a small objective — ‘Well, there’s another half million coconuts.'”

Major General R. B. Woodruff, Division Commander

____________________________________________________________________________

“Where in the name of hell are the trucks?” Quartermaster Lieutenant Robert E. Willet from Atlanta, Georgia, wanted to know.

Yes, where were the trucks?

A convoy winding upward among the hills had been ambushed. The drivers had jumped off, had pursued the waylaying Japs. When the drivers returned, the trucks were gone.

The trucks were needed to move supplies to troops in battle. But the trucks had vanished.

Bob Willet went to find out. With him went Corporal Dophus Therrien of Manchester, New Hampshire. The two slung carbines, stuck a brace of grenades in their belts, and ventured into Jap-held terrain, through sniper country and over jungle trails. They found the trucks, and a bevy of Japanese encamped around them.

A combat patrol was sent out to retrieve the trucks.

The smallest task force unit is the combat patrol. On tropical mountain paths, in villages wedged between a hill and a swamp, in terrain too forbidding to allow for passage of large bodies of troops, in guerilla-type warfare and in “mopping up,” the combat patrol becomes an indispensable tool.

“If the Jap, when cornered, would surrender he’d be immeasurably easier to fight,” the Division Commander explained to Fred Hampson, the ace front line correspondent of the Associated Press. “But he won’t. Tactically you first lick him, then you have to spend days, sometimes weeks and months rooting him out and killing him. Long, miserable days in the jungles and mountains end by burning a few Nips out of caves with flame throwers that have to be carried twenty miles on the back.”[1]

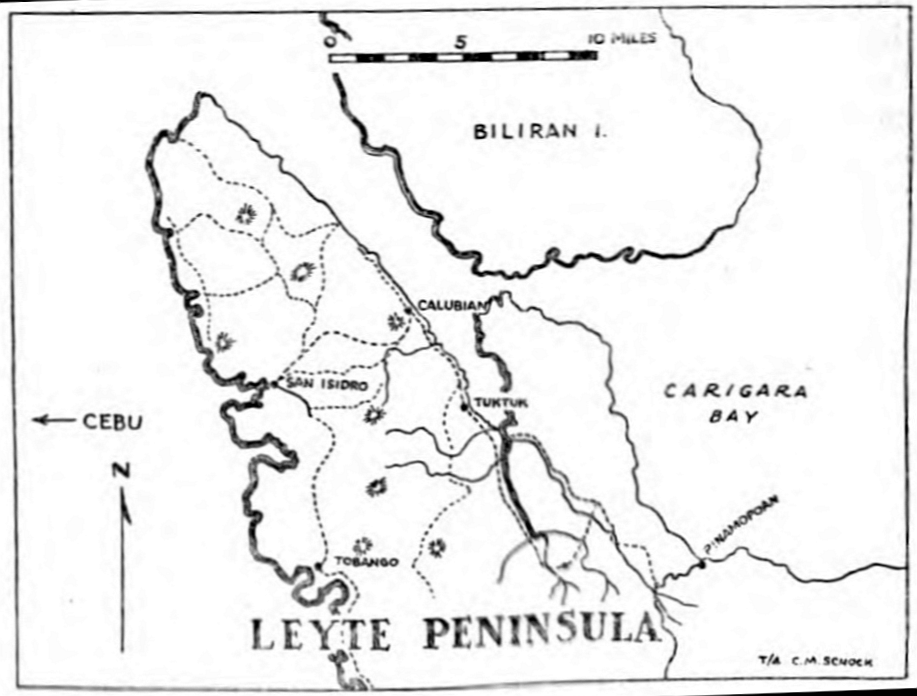

After the Beachhead battles, the sweep across Leyte and the torture in the Ormoc mountains, the Division’s forces were divided to prosecute a number of tasks. The Nineteenth and Twenty-First Regiments staged for invasions of other islands of the Philippines. The Thirty-Fourth remained to secure the coast of Carigara Bay. Later it swept the Leyte Peninsula in the north with iron brooms. In this task combat patrols came into their own. As yet there was no place on all of Leyte where a soldier could safely wander unarmed.

From November 8 until December 2 a patrol of company strength roamed the mountain country around Sinayawan. The force was commanded by Lieutenant Benjamin H. Wahle of Helena, Montana. His men lived on cold rations for twenty-five days in the worst of rainy season weather. During this period scattered Jap detachments made sixteen attacks to eliminate Wahle’s group. All failed.

On November 9 a new type of Japanese plane came down in a crash landing. Its pilot was killed. An air liaison officer, Captain John Dudney from Echo, Louisiana, decided to strip it of its equipment. But snipers got there first. They set the plane afire, then withdrew two hundred yards to guard the craft until it had burned down. When Dudney saw the flames he broke into a fast run. The snipers fired at him, and missed. In weaving and zig-zag motion, Dudney removed two machine guns and two rapid-fire cannons from the wreck. It took him three trips with a combat patrol to carry off the captured weapons.

On November 10, a group led by Sergeant Thomas Martin of Kai Malino, Hawaii, patrolled a mountain trail three miles south of Capoocan. In the wild fastness around Mount Minoro the patrol came upon a fork in the trail. Sergeant Martin stopped short. He peered and listened. There were only the sounds of falling rain, the breathing of his men, the screech of a cocadoo. A family of monkeys gamboled in the thickets. Martin split his patrol. He himself took the left fork of the trail.

In silence they proceeded among somber barriers of vegetation. They had gone about a thousand yards when a rifle cracked. The scout jumped behind a tree. Other rifle reports joined the first, and then a machine gun hammered.

Martin’s scout dropped to the ground. He tried to find the source of the shooting. Where he lay he could see nothing. In a wriggling crawl he made his way to a grassy knoll. Now he saw. There was an enemy observer crouched at the edge of a clump of wild banana. A little farther a company of Japanese was pushing down the trail. The enemy observer spotted the scout and fired. The American returned the fire with his Tommy gun. Then he withdrew fast, and told Tom Martin what he had seen.

Martin knew that the Japs outnumbered his patrol ten to one. But he also knew that if the Japs were allowed the freedom of the trail they would trap the other half of his patrol.

“Trail block!” he said.

They blocked the trail with all the fire power they could muster. Martin sent a runner to call back the men on the right fork of the trail. Eleven Japs were killed and the patrols retired without losing a man.

Later that day the enemy attacked the Sinawayan base perimeter. He abandoned eighteen corpses after a five-hour fight.

On November 11 another trail patrol was rushed by the same pack of Japs. The patrol’s automatic rifle gunner was wounded and the Japanese were closing in. Private Leo Gomolchak from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, grabbed the B.A.R. Japs in adjoining bushes tossed grenades. Gomolchak stood upright, unleashing bursts of automatic rifle fire. That saved the patrol.

On November 15, terrified natives reported that a gang of Japanese had blocked the Colasian-Ormoc trail north of Mount Minora. The Japs had bayoneted Filipinos who attempted to reach the American coastal zone. The Japs, who were living off the land, forced other natives to procure food. Terror was to prevent their escape to the coast.

A “George” Company patrol investigated. They found a camouflaged trail block. Private Marvin Edge from Rockledge, Georgia, a scout, crawled up a jungle-covered slope. He came within fifty yards of the Jap position. Still he could not pinpoint its exact whereabouts. So he stood up and yelled: “Hey!” Immediate machine gun spurts and grenading were the result. This showed Marvin Edge just where the Japs were dug in. He crawled back to his own lines. A mortar barrage destroyed the trail block.

The impact zone of the mortar blasts yielded twenty-three dead Japanese. But a day later another patrol covering the same trail met vicious fire from the same spot. The lead scout was hit twice. He collapsed on the trail. The patrol leader, Sergeant Galloway from Owensboro, Kentucky, crawled up to the wounded scout and began to drag him away. Again the machine guns clattered, and Galloway, too, was wounded. All the same, he managed to drag himself and his scout into the bushes.

Now “Easy” Company sent out a force to determine the strength of the enemy trail block, and particularly the exact location of its automatic weapons. The scouts were soon caught in the cross fire of machine guns. The patrol leader remained long enough to fix the precise location of the Jap nests. Then he gave the order to withdraw.

All withdrew, except one scout. This scout lay under the eyes of a Japanese machine gunner and he was unable to budge.

Forward again went Private Kenneth Foldoe of Bagley, Minnesota. He worked his way through scorched kunai to a point from which he could bring his B.A.R. to bear on the gunner who was shooting at the scout. Presently the Jap gunner swung his gun around and fired at Foldoe. The Minnesotan engaged the machine gun in a duel long enough to allow the scout to scurry to cover. After that Foldoe took to his heels. The patrol brought back the intelligence that the Japs had four machine guns and seventy-five men dug in astride the trail.

On November 18, “Easy” Company set out to liquidate the block for the second time. On the way a soldier died by snipers’ bullets. It was found that the wily Japs had shifted the positions of their machine guns overnight. A new reconnaissance was necessary. It was made by Private Kelcie Odom of Gunnison, Colorado.

Odom crawled into the immediate vicinity of the Japs. Then he stood up to draw their fire. When the first shots cracked, he threw himself on the ground and noted the direction from which the bursts came. The Japanese did not like it. They dispatched a sniper to kill Odom. Scout Odom saw the Jap. He watched him until the Jap stopped crawling. “Good-by, Nip,” said Odom, and shot him dead.

“Easy” Company attacked the trail block from three sides. It was carried in a hard, uphill fight. The price was a number of American lives. But the majority of the Japs were killed and the survivors dispersed into the jungle.

At one point in the fighting a lone soldier rushed a pillbox and was quickly shot down. Sergeant William Dittsworth of Clover, Pennsylvania, and a comrade crawled almost to the mouth of the pillbox. They slowly pulled the wounded soldier into a thicket. Then they climbed atop the pillbox with grenades.

That same day a band of Japanese popping apparently from nowhere pushed down a half-forgotten mountain path known as the Antipopo Trail. Undetected they reached the vicinity of Colasian.

Now, Colasian was well within the American held coastal zone. A section of the Division’s howitzers was passing westward along the coast road. At 7:30 P.M., under cover of darkness, the Japs attacked the artillery team. In the first volley two artillery men slumped off their moving mounts.

“Keep moving, keep moving, don’t stop,” yelled Sergeant Bill Hammock of East Tallahassee, Alabama.

Hammock was the leader of the howitzer section. Instinctively he preferred to risk his own life to risking the destruction of his howitzers. He kept the howitzers moving. He himself leaped from his mount and fought for the life of his two wounded comrades until help arrived.

The swamp-bound coastal road from Carigara to Pinamopoan proved as vulnerable to flanking attacks from the mountains to the south as it was to the continuous rains. Across this narrow coastal “corridor” moved the bulk of supplies supporting the Ormoc Valley offensive. With combat patrols in action over many miles of wilderness, only one understrength battalion remained to guard this lifeline against enemy attack. The regimental commander pressed the men of his Anti-Tank Company to duty as riflemen and told them to drive the Japs from the Antipopo Trail. The tank-fighters borrowed carbines and machine guns and went patrolling.

(Called the “Knee Mortar” by U.S. troops)

They pushed a thousand yards up the trail and attacked the Japs’ bivouac. Fire from rifles, machine guns and knee mortars drove the anti-tank gunners back. A second assault was also repulsed. The anti-tank men then lugged mortars up the hillside and put down a mortar barrage. After that they stormed the position. This time not a shot was fired. They found a jumble of Japanese cadavers, sixteen spider-holes, some shallow graves and nine pools of blood.

On the following day the anti-tank gunners moved against the next ridge to the south. Mortar fire drove the enemy from the crest. But the instant the barrage lifted, both sides raced for the top of the ridge. The Japs got there first, but were routed in an all-day fight. For good measure, the anti-tank gunners then occupied a third ridge still farther to the south. However, in the inky, rain-drenched night the Japanese infiltrated through jungle ravines back to the coastal road. There was no way to stop them except to corner them, one by one, and to kill them.

This is the unsung “mopping up” — bitterly fought little actions of which outsiders hear nothing. Meanwhile, at home, dark suited individuals with telegrams rang door bells in a sorrowful finale.

The Jap fighter was a tricky fellow. He may have been a “bush leaguer” in the use of artillery. He may have been an amateur of tank tactics. His teamwork was raw. But he was a brave man, not afraid of death. The compulsions of technical inferiority made him a master of night crawling, of digging holes in impossible places, of doing the unanticipated, of wrinkles as dangerous as a copperhead in a flower bed.

Any first Jap attack on a perimeter may be only a diversionary attack. Infiltrating Japs were sometimes dressed to look like women. At other times they might be wearing uniforms stripped from American dead. Japs in ambush loved to let trucks go by, then mined the track over which the trucks were likely to return. The scattered shooting of a few Jap snipers often kept a whole battalion perimeter awake from dusk to 3 A.M. — and then fell silent; but an hour before dawn a suicidal charge would strike the position in the hope that the wearied defenders had dropped off to sleep.

Snipers liked to climb tall trees growing from ravines. Such a perch gave them a good silhouette of troops moving over adjoining higher ground. Other Japs dug their foxholes to face the “wrong” direction; they allowed American detachments to pass, then mowed them down from the rear. Or a sniper would dig a good hole near a mountain trail, bury in it a mine, and then with draw a little way into the jungle. Soldiers suddenly fired on by the sniper were likely to dive into the convenient foxhole — to be blown sky-high.

There were Japs who left innocent looking sandal tracks in the mud. A patrol following these tracks in the hope of finding one Jap suddenly ran into gun blasts.

There were Japs who started little cooking fires to make Americans believe that there were Japs off guard, eating rice. A patrol intent on surprising the eating enemy blundered into an ambush instead.

There were Japs who squatted a few yards away from American wounded. The Japs shouted “Medic! Medic!” To the corpsman rushing up to help — that was unfailing death.

There was a lone Jap sniper who fired a single shot down a trail to reveal his position. But the patrol lured forward to destroy the sniper was clamped between machine gun fire from both flanks. That happened to a “Fox” Company combat patrol on November 19, near Capoocan. The patrol was saved by Private John Lomko, of Chicago, who had insisted on lugging along a light machine gun. The patrol fell back while he fired. Then he with drew, dragging his gun. Every few yards he stopped, turned around, and gave the Japs another burst of fire. John Lomko was killed in action.

On November 20, near Calubian, on the east side of the Leyte Peninsula, a patrol lead by Sergeant Jack Wheat of Fountain Run, Kentucky, was waylaid by Japs firing from emplacements which “faced the wrong way.” Two soldiers of the patrol crumpled under the hail. The remainder was nailed to the ground. The Japs then made a typical “tactical” mistake. They climbed out of their holes and launched a bayonet charge. Sergeant Wheat’s accurate shooting held them off long enough to allow the patrol to fall back into tall kunai.

On the same day, in the same manner, another patrol was ambushed in the vicinity of Capoocan. Here it was a “George” Company scout, Private Roy Soden from Shrewsbury, New Jersey, who saved the patrol with twenty-four aimed shots from his Garand.

In the Mount Minoro wilderness, “Easy” Company tangled with a force of Japanese who had harassed traffic on the coastal road. The Japanese were discovered entrenched on a hill. The company attacked. The attack was repulsed. The company reorganized and attacked again. Again it was repulsed. A third attack bogged down in a sudden, swamping rain storm. A fourth charge, following an artillery barrage, attained the hilltop. “Mopping up”; but it cost eleven American lives.

Not far away, also on November 20, a nineteen-man patrol commanded by Sergeant Thomas Turner of Oakland, California, defended another hill against three wild Banzai assaults.

Shortly after dawn of November 21 a patrol moving through hill country south of Colasian came upon the bodies of three Filipino men, four women and two children. All had been bayoneted in the abdomen. Their belongings, scattered about them in the brush, indicated that the group had been fleeing from Jap-held mountain regions. They also indicated that Japs were prowling nearby.

“Easy” Company patrols were dispatched to find and to destroy the Japs. At 10 A.M. a reconnaissance squad heard them talking in the undergrowth. The squad halted, and its first scout crawled forward. Twenty-five yards from the enemy position the scout met machine gun fire. He took off his helmet and propped it into a bush. He then wriggled hurriedly under a nearby log and lay still. The Jap gunner kept firing at the helmet. The scout spotted the emplacement and brought back the required information. “Easy” Company outflanked the Japs. After the skirmish, four teen dead enemies were found in one spot, eleven at another, and tracks of blood showed that wounded had been dragged into the jungle.

On November 22 another “Easy” Company team went hunting for an enemy artillery observation post. Distant Jap guns had put harassing fire on the coastal road; it was assumed that their observers lurked atop one of the heights bordering the shoreside swamps.

The patrol’s scout, Charles Lindenmuth of North Platte, Nebraska, was first to discover the hostile observers. The post was protected by a machine gun. Lindenmuth crept toward the machine gun with rapidity and skill, and suddenly he opened fire. This kept the machine gun out of action. Meanwhile, the other men of the patrol made short shift of the observers’ party. The shelling of the coastal road stopped.

But the Japs struck back. During the night, suicide detachments filtered through the inscrutable ravines toward the coast. They seized a section of the road and mounted machine guns in the swamps and on a ridge overlooking the beach. The first supply convoy which passed after dawn was ambushed. The Japs fired on the leading truck, wrecked it, and so stopped the whole convoy. Then they tossed mines to the front and the rear of the stalled column. A by-pass was not possible. Men were hit. A fire fight developed.

Corpsmen endeavored to rescue the wounded. But from both east and west the road was blocked. The attempt was then made to evacuate the wounded by boat. But the boat was driven off by gunfire from the ridge which dominated the beach.

Driving along the road in his amphibious truck came Private Lewis W. Nail, of Blue Jacket, Oklahoma. He heard the shooting and jammed on his brakes and grasped his rifle.

“What’s the trouble?” he asked.

“Can’t get the wounded out,” he was told. “We tried a boat. The Nips shot it full of holes.”

*Let me try,” said Nail.

He did, with the help of another soldier named Bill Mostovyk.

Together they maneuvered the amphibious truck off the road, 4cr\x3 the beach and into the water. They swung offshore in a wide circle. Then they churned head on into the trouble spot. The machine gun on the ridge fired angrily. The amphibious truck hit the beach. Its drivers’ guns were blazing. Some of the wounded were loaded into the truck. Still firing, the amphibious Samaritans headed out to sea. The remaining wounded were brought to cover by two other volunteers who drove a weapons carrier straight into the firing zone.

To an “Easy” Company platoon was given the mission of destroying the machine gun nest on the ridge. After five fruitless attacks the machine gun was still in place. It was protected by enemy sharpshooters in a ring of foxholes around it. The ridge approaches were a 70° incline, burned clear of brush. Mortar and machine gun fire from the swamps below took no effect. As long as the Japanese gun remained in place, neither the beach nor the coastal road would be clear to traffic.

On November 24 the ridge-top nest was attacked for the sixth time. The patrol assigned to do the job was one decimated platoon, fourteen men strong. The patrol leader, Staff Sergeant Michael Blucas from Ralphton, Pennsylvania, led his men to the base of the ridge, and then up the steep slope in short, daring rushes. A seasoned rifleman needs from three to five seconds to aim his weapon and to squeeze its trigger. No single forward, uphill rush, therefore, could take more than three seconds. In three seconds a man can run ten yards, or climb two, and then drop to the ground before the bullets aimed at him can strike their mark.

In two to ten yard rushes Sergeant Blucas and his team reached the crest of the slope.

But where, exactly, was the hostile nest? Scrubby brush covered the ridge top. To see more than five yards ahead one had to stand up. And standing up, one drew fire.

Two men stood up to draw the Japanese fire. One was Sergeant Blucas. The other was Private Louis H. Baker of Clinton, Iowa. They stood up and the machine gun fired and revealed its position. The machine gun now fired a continuous series of bursts which swept the whole crest. In order to enable the squad to advance, someone again had to stand up to pin down the hostile gunners with aimed, direct shots.

Louis Baker stood up and fired. With eight shots he killed three Japs. Then Baker clutched his chest and fell.

The machine gun continued its deadly rat-a-tat. It was silenced in the seventh assault.

Michael Blucas, too, was killed in action.

Colonel Clifford and one hundred men of the force which had fought on Kilay Ridge were in Calubian when intelligence arrived that three thousand Japanese troops had landed at San Isidro, on the west coast of the Leyte Peninsula. San Isidro lies five miles due west of the village of Calubian. Apparently the purpose of this “counter invasion” was to occupy the peninsula for a last ditch stand on Leyte Island. Native refugees told Clifford that the Japs were looting and murdering civilians.

The mud of Kilay Ridge still clung to Clifford’s boots. He summoned his officers, including two leaders of a guerilla regiment, a Major Nazarino and a Captain Alejandre.[2] The guerilla officers assured him that a force of guerillas was on its way to Calubian. This was the crack Ninety-Fifth Guerilla Regiment. But it would take them several days to assemble their men into a striking unit. However, the barrio people of the Leyte Peninsula were a militant crew. Colonel Clifford armed local volunteers with captured Japanese rifles. He dispatched an eight-man patrol to block the road from San Isidro. The patrol was ordered to live with the natives, to report all developments, and to fight delaying actions when attacked by superior forces. The situation was perilous.

There existed on Leyte previous to the American landings a guerilla organization of about four thousand armed men. Their mission had been primarily one of intelligence and of harassment. They were of slight help in the Division’s battles on Red Beach, the Leyte Valley and on Breakneck Ridge. However, in the sweeping of the Leyte Peninsula, the guerilla units were much in evidence. They patrolled aggressively and brought much information on enemy strength and dispositions. They disrupted enemy communications, killed stragglers, and forewarned civilians of impending operations in given districts and villages.

The native village capitans used native “trotters” to inform Clifford of every move made by the Japanese. The “trotters” were barefooted boys, armed only with curved bolo knives. They could trot an average of five miles in an hour. The village capitans sent their intelligence in relays from barrio to barrio. When a messenger became exhausted, another native boy grasped the message and trotted on. A typical message was: ‘To Colonel Clifford. Japs here. Hurry.” On one occasion a message was lost when the “trotter” found a sleeping Japanese, cut his throat with a bolo, looted his pockets, and after that went off on a tangent, looking for more.

It was Clifford’s plan to induce the Japs to scatter their San Isidro forces, then to prevent them from re-uniting their strength. Their separate detachments could then be defeated one after another. The doings of guerilla patrols soon caused the Japs to occupy the villages of Hubay, Daha, Tabong, Tuk-Tuk and Boho. Signs of unrest caused the enemy to send “security groups” in all directions. In Calubian, Clifford traced all these movements on his battle map.

The first eight-man American patrol to penetrate the peninsula was led by Lieutenant Thomas J. McCorlew of Cleveland, Texas. It boldly entered the outskirts of San Isidro at dawn, December 8, climbed a hill at the rim of the town and there lay in observation for two full days. The Japanese commanders were unaware that a young man from Texas, armed with high-powered binoculars, was gazing steadily through the windows of their headquarters.

The patrol reported on December 9 that five hundred Japs, armed to the teeth, were marching on Calubian.

Clifford bound every man in his force to service as a rifleman. They set out to meet the Japs. Civilians from Calubian were evacuated to Biliran Island, across two-mile-wide Biliran Strait.

Soon a native runner bore word that guerillas were locked in battle with three hundred Japanese at Tobango, five miles south of San Isidro. Clifford called for reinforcements.

Reinforcements arrived at midnight. There were two com panies of riflemen, two sections of machine guns and mortars, and two field cannon. The American force on the peninsula now totaled nineteen officers and three hundred and sixty-eight enlisted men.

At 10 P.M. an advance patrol of seventeen men dug in on a grassy knoll near the barrio of Tagharigui. The patrol leader, Lieutenant Oakley W. Storey, from Los Angeles, had a feeling that the grass around him was ”lousy with Nips.” At that time all was quiet. A pale moon shone through ragged cloud flags, and a light night wind stirred the grass in silvery waves.

Exactly at midnight a piercing “Banzai!” rang out. In an instant the patrol perimeter was in a fiendish uproar: flares, fiery stabs, bursts of gunfire and howls of rage. More than one hundred Japanese charged the knoll with fixed bayonets. Through grass and moonlight they had crawled to within fifty yards of the patrol before the Banzai rush began.

The Japs plunged head-on into the fire of the B.A.R.’s. When a score of Japanese rush an automatic weapon they seem content when sixteen die and four get through. It is as if they embarked on a mad gamble that the automatic rifles would jam. The B.A.R.’s did not jam. Lieutenant Storey, wounded four times, spotted a Japanese captain who yelled, “Banzai! Banzai!” The Jap swung a Samurai saber. The Californian met him with a pistol. And the pistol jammed! The Jap officer lashed out with his sword. Storey ducked; he rammed his head into his foe’s stomach. He seized the Jap’s wrist and twisted until it snapped. Then he seized the Samurai sword. The Jap captain fell, beheaded by his own weapon.

The Japs continued to press their attack after daylight. Standing in the middle of the San Isidro trail a B.A.R. gunner named Orville Schuler from Wathena, Kansas, killed four Japs and wounded seven. Squatting in a foxhole not far from Gunner Schuler was a rifleman named Onnie Johnson from McNinnville, Oregon. Johnson heard the yelling of the Japs who attacked Schuler. But from his foxhole he could not see the attackers. Out he jumped, to a tree at the edge of the trail. That was better. He could see the Japs now. He brought up his Garand and killed three more.

All onsets were repulsed. Clifford’s men counter-attacked behind a rolling mortar barrage. Five times they were thrown back. The sixth thrust ended in hand-to-hand fighting. There were seventy-eight Japanese cadavers littering the grass, and much discarded equipment. The equipment was new, and the cadavers appeared to have been fresh and well-fed Japs. A count of noses showed six American dead and ten American wounded.

About three hundred and seventy Americans now held a “front” twenty thousand yards long and five thousand yards deep.

“As numerous small and scattered fights developed on the Leyte Peninsula, new methods of operation were developed. The terrain of the peninsula is composed of low, grassy ridges behind a fringe of high hills along the coast. The grass is not deep, and observation from the highest knolls is effective for miles.

“It was thus impossible to conduct any daylight movements without discovery by the Japanese. We had, however, the advantage of Filipino Scouts who knew every inch of the territory. Hence, night movements became common. Detachments would move out early enough to reach objectives just before daylight, attack in the dawn and men rest the remainder of the day, maintaining observation from vantage points.

“This technique threw the Japanese completely off stride and resulted in the inflicting of many casualties upon the enemy with only small loss to us. Japs were being killed every day.”

(from a Field Report)

A one-time accountant from Seaside Park, New Jersey, led a band of guerillas in one of the most adventurous actions on the peninsula. The ex-accountant was Major George D. Willets. The slim, handsome young officer had joined Clifford’s battalion only a few days before the opening days of the campaign. The colonel had made the newcomer his executive officer. The job of a battalion executive officer is administration. What Major Willets wanted was action.

He started out at 4 A.M. in a tropical night rain at the head of a patrol of Americans and fifty guerillas. His mission was to isolate a series of hills near Taglawan, which were known to be occupied by the Japanese. In the rain-drenched dawn the little task force reached its objective and set up its machine guns. The Japs were unaware of its presence. The former accountant decided to give the Japs the surprise of their lives.

He jumped up and led the charge of his mixed host.

“Hear, all guerillas,” he shouted. “Follow me! Long live the Philippines! Long live the guerillas! Long live Rizal, Quezon, Osmena!”

Protected by cross fire from machine guns the guerillas charged, Willets out in front. They reached the crest of the first Japanese-held ridge. Willets’ shouting spurred his warriors into a joyous kind of ferocity. The guerillas saw the major hurl hand grenades into enemy foxholes. They saw three Japs die under their commander’s grenades. There was a melee of shooting, shouting, throat-cutting, of fleet bare legs, bobbing straw hats and curved bolos in tawny fists. Terror stricken, the surviving defenders sprinted downhill.

Willets ordered the machine guns forward to provide another curtain of protective five. The guerillas charged the second Jap-held ridge. Again they drove the Japanese down the slope in a close quarters fracas.

Not far away, in a shallow ravine, were two abandoned Japanese machine guns. Midway between the guns a dead Jap lay, face down and arms thrown wide. Willets ordered a squad of guerillas to go down and to secure the guns. The guerillas consulted, then shook their heads. They pointed at another hill beyond the ravine.

“Maybe Japs on that hill,” they said. “The Japs will shoot when they see us go get their guns.”

Major Willets shrugged his shoulders. “Watch that hill,” he told them. “When you see Japs, shoot ’em.”

With that the accountant from New Jersey scrambled down the slope toward the abandoned guns. He quickly searched the dead Japanese for documents, but found none. Then he walked to one of the guns, cradled it in his arms, and clambered back to the top of the captured ridge. “You see,” he told the guerillas. “Nothing happened.”

After that, Willets once more descended into the ravine to secure the second machine gun. The machine gun had disappeared. With it had disappeared the Jap “corpse.”

The Japanese then counter-attacked. Four counter-charges were repulsed. A rapid check showed Willets that his guerillas had expended all their ammunition. Whereupon he withdrew his combined force to their original morning positions. On the captured — and jauntily discarded — ridges they left one hundred and twenty-nine enemy dead.

On the night of December 10, Japanese counter patrols assaulted a height known as Guard House Hill, in the vicinity of Calubian. In the surprise sally, carried out in pitch darkness and rain, one American was killed and four were wounded. Before the stab was warded off. Aid Man John Folk of New Kensington, Pennsylvania, dashed across the line of the attacking Japs and hid the wounded. He remained on guard beside his patients for the rest of the night. The Japanese, apparently, took fearless John Folk as one of their own.

One of the wounded soldiers was Private Francis Lockwood from Boyeville, Wisconsin. He had been shot through the leg, but insisted on returning to the fight. He said, “I don’t pull my trigger with my toes.” He recovered his rifle and rolled off into a clump of kunai. From there he fired on Japs dodging past him in the darkness.

The wielders of the iron brooms which swept the Leyte Peninsula worked with rapidity and dash. During the many skirmishes of December 11, Private John Mallon of Bayside, New York, stood upright in the grass to lure the Japs to fire at him and so to disclose their masked positions. He then destroyed three of their nests by walking into them, tossing grenades.

Private Harry Schildt, from Browning, Montana, was wounded by flying shrapnel. He refused first aid and continued to skirmish. His commanding officer then ordered him to go to the rear. After they had bandaged his wound he escaped the corpsmen and rejoined the fight.

During the same day, Lieutenant Robert Caldwell from Turtle Creek, Pennsylvania, conducted his rifle platoon in a hunting trip across many streams, over ridges and through valleys. By evening their day’s bag was thirty-nine dead Japs.

Private Santo Magazzi of Bethel, Connecticut, led his squad across an open valley and knocked out a hostile machine gun nest. On the way one of his men sagged in enemy fire. Magazzi returned in broad daylight, peppered by snipers, to rescue his comrade. But he found that the soldier was dead. Magazzi also died in action.

After the capture of a hilltop, Private Dana Wallace from Dunbar, West Virginia, saw a lone Japanese leap out of the ground and charge an officer with a bayonet. The officer was oblivious of the danger. Wallace riddled the Jap. The bullets struck within arm’s reach of his startled commander.

Private Paul Garland of Ingalls, North Carolina, a scout, crept up to a Japanese machine gun nest, sprang into the emplacement with Indian war whoops, seized the machine gun and slew its gunners with bullets made in Nippon.

Another machine gun roost had pinned down a whole squad on an exposed slope. The slant-eyed gunners were sure of their kill. For the Division’s men it was a situation in which one must give his life to save the whole team from destruction. Private Eugene K. Tupponce of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, armed with a submachine gun, worked himself up the grass-covered slope. And suddenly he stood upright. The others heard the wood pecker rippling of his Tommy gun. They rushed the Jap roost and destroyed it. Gene Tupponce lay dead, and there seemed almost a smile on his young face.

On December 14, a patrol on a night march became marooned in darkness and rain near the village of Gustosan. Sheets of rain blinded the patrol. Men could not see the rifles they carried in their hands. Gullies between the ridges filled with water. The patrol sat in a huddle, waiting for the deluge to pass. It was near midnight.

At 1 A.M., December 15, a guard of the patrol heard a hoarse grunt in the darkness. He also heard the squishing of boots approaching through the downpour.

“Japs!” he yelled.

The raiders were upon them before any man in the patrol could fire a shot. Their screeching and the absence of firing made the encounter eerie beyond words. It was as if a bunch of werewolves had abruptly popped out of the mushy earth. The Japs had dots of luminous paint on their helmets so that they could recognize one another in the dark. These dots, uncovered when they launched their assault, glowed like darting, unblinking eyes. They also were the Japs’ undoing. One man’s experience in this Jap-fight was the experience of all. Take Private First Class Eugene E. Madden of Studley, Kansas.

Madden had sat drowsily in the rain, wishing that it would stop. He had fingered in his pocket for a wallet which contained the picture of his girl and a picture of his parents. The wallet had soaked through and the pictures had turned to pulp, and they were mixed with a box of matches and some cigarettes which had dissolved in Madden’s sweat and Leyte’s rain. Madden felt miserable. Suddenly a screeching Jap jumped on top of him.

Madden rolled over. A Japanese hand clutched his throat, and Madden grasped a wrist and felt that the Jap’s fist clutched a dagger. He gave a great heave. He kicked his assailant in the face with both feet. The Jap grunted and thrashed. Madden stood up and kicked at the thrashing Jap. At this point a bayonet sliced into Madden’s back.

Madden lunged forward. He felt the bayonet withdrawn with a brutal jerk. Behind him a voice snarled an outlandish word. Madden rolled a few feet. He felt his blood, warm and sticky in the rain. The blood was running between his buttocks and down his thighs. But he felt no pain. He felt stronger than he ever before had felt in his life. His hands found a rifle. He grasped the rifle and lunged in the direction of the alien snarl. He brought up his rifle in a vertical butt stroke. It caught the Jap under the chin, then ripped upward across his mouth, his nose and his eyes. It also knocked off his helmet.

The Jap reeled. There was an outcry of pain. An instant later he charged. Madden felt the bayonet pass inches from his neck. He smashed his rifle butt into the Jap’s face. He followed that up with a kick to the Jap’s groin. Then he sprang on top of the Jap and both of them rolled in the rain. The Jap had sunk his teeth into Madden’s leg. Madden finished him with a trench knife.

All around him his comrades and the Japs were fighting tooth and claw. Madden pitched in. Suddenly there was a shrill whistle. As if by some magic the Japs disengaged. They found and picked up their wounded. Seconds later they had vanished in the night. They left three battered corpses.

After dawn another patrol probed for the Japanese nests. In this probing a scout named Charles C. Puglisi, from Pittsburg, California, found a Jap position hidden on the reverse slope of a ridge. On the way back to his patrol Puglisi was critically wounded by a sniper. But he crawled on and brought back the intelligence he had gleaned. He died before he could receive his Bronze Star Medal, which was sent to his widow, Anna Puglisi.

On December 17, near the barrio of Fortuna, Private Donald Ritter of Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, was a member of a combat patrol which had been lured into an ambush by a false report given by a pro-Japanese native. Donald Ritter pushed a machine gun forward and fired into the ambush to enable his patrol to wriggle out of the trap. Donald Ritter was killed in action.

On the morning of December 21, a two-man patrol near the headwaters of the Nipa River, spotted a column of several hundred Japanese moving toward a village named Tuk-Tuk. The two scouts were Private Noel Ellsberry of Perkinston, Mississippi, and Technician Robert Pridemore of Dema, Kentucky. They decided to scale nearby Mount Banao which would give them better observation of the Japanese column. They did not know then that a six-man enemy patrol was scaling the other side of the same mountain.

On the summit they came face to face. The two scouts fired. One Jap fell dead, two bobbed away, wounded. The others ran downhill. But an enemy machine gun opened fire from across a ravine. The scouts were pinned down, but they still were able to pursue the survivors of the hostile patrol with well-aimed shots. When the machine gun jammed they crawled away. Keeping to the ridges they followed the enemy column into its bivouac area. Then they returned and told their officers what they had seen.

That night, combat patrols and guerillas led by Major Willets were dispatched to surround the bivouac and attack it at dawn. Heavy mortars were loaded aboard four amphibious tanks which nosed up the shallow Nipa River toward Tuk-Tuk. At dawn the bivouac was surrounded. The “Alligators” opened point blank fire. Machine guns clattered on the heights overlooking the town. The majority of the Jap force had been caught cooking their breakfast rice. The patrols then charged downhill, led by the indefatigable Thomas McCorlew. Well over a hundred Japanese were killed. The survivors took to the brush and were caught and cut down by other patrols waiting for them on the twisting trails.

Perusal of abandoned enemy equipment showed that the enemy had looted everywhere. Soldiers’ sacks were crammed with table linen, silverware, jewelry and other items, including women’s brassieres. One dead Jap had even a baby’s high chair tied on the top of his field pack.

Another combat patrol reinforced by sixty guerillas pushed brazenly to the coast of San Isidro Bay, the camping ground of more than a thousand Japs. The mission of this patrol was to split the bulk of the enemy into separate lesser forces. This they accomplished by impudently pricking the main force. There followed a series of forced march maneuvers which drew Japanese pursuit parties to widely divergent points. In their David-Goliath assault the patrol had slain twenty-five Japanese. But one soldier and the patrol leader, Lieutenant Charles T. Dyer of Montgomery, West Virginia, had been killed in action.

Sergeant Bernard L. Purdy of Killbuck, Ohio, now took charge.

“How are we going to get out of here?” he asked himself.

The Japanese were strong in the north, south and east of the patrol. There remained only the sea in the west. This sea, Purdy knew, was not a friendly sea. It was patrolled by Japanese gun boats.

Purdy contacted some native boatmen. They refused to put to sea at night. Not for all the chewing gum and cigarettes in the pockets of the patrol.

Purdy decided to commandeer a ship.

Scouts roamed the shoreline. They found a sailing banca lying high and dry on a beach. Purdy posted guards on both ends of the beach. The rest of his force brought the ship to water after much tugging and heaving. They were helped by a dozen native women who said that they were fugitives from Cebu. All hands then crowded into the leaking craft, Americans and guerillas. The refugee women clamored to be taken along.

“Climb in,” growled Purdy. “Only keep quiet.”

There were neither paddles nor a sail. Emergency sails were rigged from ponchos. The night was dark. Cloud banks cut off the light of the moon. A brisk wind blew. After two hours’ sailing, the silhouette of a patrol craft pushed over the horizon. Purdy doused his sails. No one spoke. No one smoked a cigarette. The patrol boat slunk past them and out of sight.

An hour later a second patrol craft churned by, nearer than the first. Americans and guerillas alike lay flat atop of one another. The native women did the sailing.

Abruptly a brilliant burst of light showered the banco. It was a mortar flare, floating from a paper parachute. The women chattered in fearful confusion. The soldiers quietly cocked their guns.

“Boat ahoy,” a voice rang over the water. “Who are you?”

It was an American voice.

Purdy shouted back: “United States Infantry — take it easy.”

Aboard the P.T. boat the voice rumbled, “Well, I’ll be a son of a bitch.”

The Leyte Peninsula was finally swept clear of Japanese by a battalion[3] commanded by Major L. Snavely of Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

An artillery barrage cornered and destroyed three hundred not far from Tuk-Tuk. A hundred more were killed near Taglawan. Others were destroyed at Baha, Tobango and on the shores of Arevele Bay. Sergeant Gordon Bailey from Washington, West Virginia, and Private William Daly from Boston, marched into San Isidro and killed sixteen Japs in a house-to-house search. Only one enemy surrendered alive.

In a last gesture of defiance a swarm of Japanese charged with bayonets tied to the ends of bamboo poles. Many others climbed into a tidal cave. In a protest against circumstances over which they had lost control they blew out their innards with grenades.

It was Christmas, 1944.

(Continue to Chapter 17: Island Raiders)

________________________________________________

[1] Major General R. B. Woodruff, who previously commanded troops in Europe, assumed command of the Twenty-Fourth Infantry Division on November 18, 1944. Major General F. A. Irving, former commander, took over the command of Eighth Army garrison forces.

[2] In a report on the activities of Guerilla Captain Benigno Alejandre of San Isidro, Leyte, Colonel W. W. Jenna, commanding the 34th Infantry Regiment, stated: “Captain Alejandre has been an invaluable addition to our forces and has contributed materially to the success of this campaign. His intimate knowledge of the area and of the operations of the guerilla and civilian forces since the days of Bataan, combined with a keen insight of Japanese characteristics, has been of inestimable value and has saved many American lives.”

[3] Second Battalion, Thirty-Fourth Infantry Regiment.