Editor’s note: The following is extracted from True Heroism and Other Sermons, by R. N. Sledd (published 1899).

“I am a Pharisee, the son of a Pharisee.” — Acts xxiii, 6.

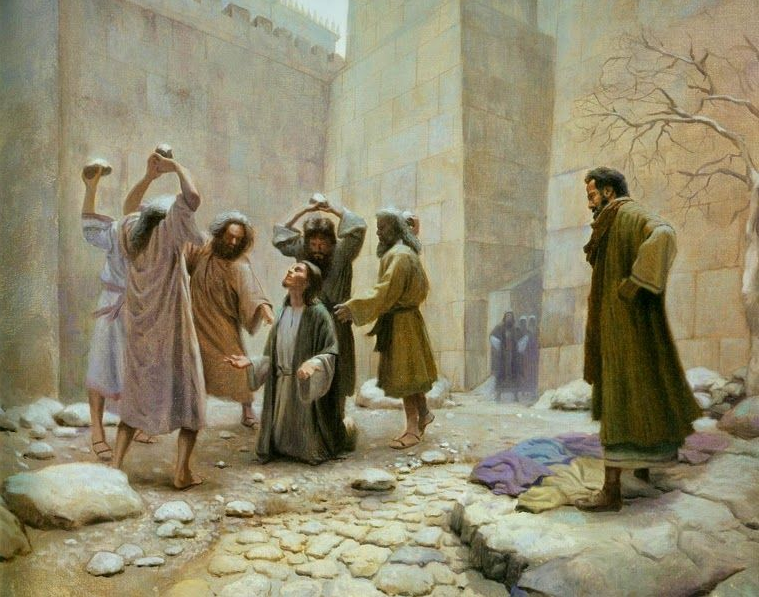

Saul first appears in gospel history in connection with the martyrdom of Stephen. He was a willing and approving spectator of his death. He was then a young man, probably between twenty-five and thirty years of age. But his character was well matured; his opinions were formed; and his convictions were deeply rooted in his intellectual and moral being. He was a fully developed Pharisee, both in theory and in life. He says of himself: “After the most straitest sect I lived a Pharisee.” According to the Pharisees’ interpretation of the law, and of tradition, which with them had all the authority of law, he was blameless. He had all the scrupulousness of his sect with respect to religious observances, all their self-righteousness and intolerance, together with the fiery zeal of an ardent, impulsive nature.

But his religious character was not a spontaneous growth; nor was it entirely or even chiefly the result of his own studies. He had freedom of will, it is true, and might have been a Sadducee, an Essene or an idolatrous apostate. But all the influences that operated on him from the cradle to maturity tended to make him just what he was; and scarcely anything less than such a miracle as occurred while he was on his way to Damascus could have made him anything else.

He was a native of Tarsus, the capital city of Cilicia, a fertile and densely populated province of the Roman Empire in Asia Minor. The population of Tarsus was composed of Cilicians and other Asiatics, Romans, Greeks and Jews. The commerce of the city was very extensive. It was wealthy, luxurious, licentious, and like Athens, with the exception of its Hebrew population, was wholly given to idolatry. It was renowned also for its literary culture. Its schools rivaled those of Athens and Alexandria. Augustus made it a free city. Either by virtue of this act of grace on the part of the Emperor, or as a reward for some special service, Saul’s father enjoyed the immunity of a Roman citizen. Hence said he, “I was free born.”

How far these surroundings of his childhood affected his subsequent life it is impossible for us to determine. It is plain that he saw nothing in the corruption and excesses of the Gentiles to attract him; they tended rather to awaken in him a disgust for the pagan civilization and to intensify his love for the religion of his fathers. The seductions that attract and destroy some men are profoundly repugnant to others. They recoil from them, and by their recoil become more firmly established in virtuous principles. Thus the very wickedness of Tarsus, so flagrant and unblushing, may have contributed to the quickening of virtuous emotions and the unfolding of religious sentiment and character in the young Hebrew.

It is very probable that much of his classic culture is due to his residence in Tarsus. He shows in his epistles an acquaintance with several of the Greek poets of minor fame, and with the philosophy, mythology, and social habits of the Gentiles.

It was there also that he learned the trade of a tent-maker. There was the good custom among the Jews of requiring all boys, whatever the position and circumstances of their parents, to learn some useful trade. All useful trades are honorable. That of tent-maker was both honorable and profitable. The material for the cloth was supplied by the goats of Cilicia, and a ready market was found both at home and abroad. This trade served him a good turn in his after life on more occasions than one. It enabled him to say to the churches, “I was chargeable to none of you, but labored with mine own hands.”

If we look into his immediate family and home life, we shall find that, from his infancy, there were powerful Judaic influences operating upon him, and all helping to make him what he became in his manhood.

The Jews at this time were divided into Arameans and Hellenists, so-called from the languages which they spoke. The former comprised the Jews of Palestine and the countries east and north. These spoke the Chaldaic and Syriac languages, which were dialects of the Aramaic. The latter comprised the Jews of the west and south, who spoke the Greek or some one of its dialects. The former used the Scriptures of their fathers; the latter the Septuagint, a Greek translation, which was made and published at Alexandria, in Egypt, in the third century before Christ. The former were true to Jerusalem, its temple and worship, and scrupulously observed the sacred festivals. The latter built a temple and for a short time offered their ceremonial worship at Alexandria. The former held to the law and to the traditions of the elders as its only admissible but authoritative commentary. So jealous were they of the introduction of foreign ideas that they pronounced a curse on any one who taught his sons the learning of the Greeks. The latter were more liberal in spirit; with the Greek language they imbibed much of the Grecian spirit, yielded to the charm of its culture, adopted many of its habits of thought, and to a large extent incorporated its philosophy with their religion. The Judaism of the Hellenists was a combination of Mosaism and Platonism.

Saul’s father, though living in what might be called a Greek city, was an Aramean. His language was the Hebrew. All his religious thinking and prejudices were deeply averse to the free thought of the Hellenists. The ancestral faith and worship and the peculiar and exclusive privileges of his people were the foundation and capstone of his moral life. Like his son he was a Hebrew of the Hebrews.

But his own section of the people — the Aramean — was divided into different parties of different tenets and shades of belief. There were the Zealots, who were political and religious fanatics, whose religion consisted chiefly in hatred of the Roman power and zeal for the liberation of Israel; and the Herodians, who saw in the power of the family of Herod the pledge of the preservation of their national existence and the fulfillment of their Messianic hopes; and the Essenes, who retired from the great centers of religious, political and commercial life and occupied themselves with the dreams of mysticism and the austerities of asceticism; and the Sadducees, who rejected the doctrines of the resurrection and the existence of angels and spirits — who adhered to the moral precepts of the law, but opposed tradition and formalism. They were the rationalists of the age.

But the most numerous and powerful of all their sects were the Pharisees. Though excluded by Herod from high official positions, their influence with the masses of the people was almost unlimited. They were the inheritors of that exalted type of Judaism by which religion was reformed and restored on the return from captivity. But had the reformers, Ezra and Nehemiah, returned at the time of which we speak, they would not have recognized the inheritance. Dry and scenic observances, vestments and attitudes had supplanted the life and power of godliness. There were no doubt upright, though mistaken, souls among them; but as a party they were given up to forms and ceremonies — not only such as their law enjoined, but all that tradition imposed or the ingenuity of their elders could invent. The spirit and principle of these observances was essentially interested and mercenary. By this means they thought to create merit for themselves before God. There was merit in tithing mint, and anise, and cumin. Merit in alms, in repentance, fasting, faith and prayer. The greater their exactness with respect to the traditional minutiae of religion, the more frequent their fasts and the longer their prayers, the greater their merit and the surer their title to heaven. It is not surprising that an arrogant self-righteousness should have been the result of this belief. The Pharisee was nothing more than consistent when he said to others: “Stand thou by thyself: come not near me, for I am holier than thou.” We may learn something of their idea of their worth in God’s estimation from these words of one of their sages: “Each Hebrew is worth more before God than all the people who have been or shall be.” Surely spiritual pride and self-sufficiency could not go beyond this!

Saul’s father was of this sect. His Aramaic prejudices led him to reject everything that savored of the liberalism of the Hellenists, while his Phariseeism constrained him to observe both what was written in the law and what had been handed down from one generation of their elders to another, with the ever accumulating exactions of a hard and lifeless formalism.

In this atmosphere Saul was born, and from the moment his mind and heart began to unfold and receive impressions from his mother’s songs or his father’s eye and mien, or the surroundings and conduct of their home life, he began to be a Pharisee. His father’s broad phylacteries, long prayers, frequent fastings, and multiform observances, could not fail to exert a profound influence upon him. More over, as physical defects or excellencies are often hereditary, so may be a religious bias and intellectual peculiarities. It was said of a certain man that “he was born a Covenanter.” When we think of the long line of Saul’s ancestry, all characterized by the same modes of thought and the same prepossessions, and the same exalted conceptions of their exclusive privileges and dignity, it is not too much to say that he was born a Pharisee. When to his inbred proclivities we add the example and counsel of the father, we scarcely see how the current of his life could have taken any other direction.

It was a saying of the Talmud that “At five years of age the sacred studies should be commenced; at ten the youth should devote himself to tradition; at thirteen he should know and fulfill the commandments of the Lord; at fifteen he should perfect his studies.” Beginning such a rigorous course of instruction and discipline at such a tender age one of two results must follow — either aversion and disgust or interest and proficiency. The latter was the result with Saul. He not only entered with zeal on these studies but became eminently proficient and so thoroughly indoctrinated as to win, while yet a young man, the admiration and confidence of so grave a body as the Sanhedrim.

While yet a boy he was sent to Jerusalem to complete his education. He was placed in the school of Gamaliel, the most celebrated Rabbi of his age. A famous precept of the Rabbins was, “Set a hedge about the law and make many disciples;” that is, preserve the national institutions by a rigorous tradition and teach the traditions in numerous schools. These schools succeeded the ancient schools of the prophets. There were several of them in Jerusalem. That of Gamaliel was the most thoroughly orthodox and the most popular. He appears to have been the most skillful of all the doctors of the law. There are indications that he was less in bondage to the spirit of a narrow literalism than many others; yet he did not go beyond the standpoint of a pure legalism. He was not a man to delude the conscience, but was honest and sincere in his beliefs and outspoken in their expression and defence. But his evident candor only increased his power and gave to his Phariseeism a deeper and stronger hold on his pupils.

Saul embraced his teaching with all the moral earnestness and ardor and infused into it all the passionate vehemence of his nature. Gifted with a strong and keen intellect, in a few years he acquired all the learning of his master.

His education is now complete. The process begun in his father’s house and finished under Gamaliel could scarcely have had a different issue. He comes forth from the feet of his teacher with his mind filled with the most exalted and exaggerated views of the prerogatives of his people, their ancient dignity and coming glory, and his spirit thoroughly imbued with love for his religion and zeal for its advancement. In the completeness of his devotion he could see no excellence in, and had no toleration for, anything else. He is a full-grown Pharisee.

We now lose sight of him for a season. But great religious events were taking place in Jerusalem. Jesus has died, arisen from the dead, and ascended to heaven. Pentecost has come. The inspiration of the Galilean fishermen, and their works and preaching, is shaking the ancient hierarchy to its foundation. The holy city and the surrounding country are in commotion. A mighty revolution is taking place. Every day it gathers strength and momentum. The scribes and doctors, the priests and elders of the people see themselves about to be set at nought, their power broken and their sanctity and wisdom despised. A man with Saul’s intense religious feeling and strong convictions could not be quiet at such a time. Nor could he see the people becoming obedient to the faith and following such guides as Peter, James, John and Stephen, without having his soul as deeply stirred within him as when he afterwards looked on the idolatry of Athens. His pride, his self-righteousness, his devotion to the law, his love of ritualism, every element of his Phariseeism was shocked and insulted by the new faith. He seemed at length to regard the preaching, praying and miracle working of the disciples, and the believing of the people as an affront personal to himself. His deepest hatred was awakened. From a spectator on the occasion of Stephen’s death we find him next entering private houses and arresting men and women and committing them to prison, and by every means in his power distressing and making havoc of the church.

This was his Phariseeism in full fruitage. It was the natural product of the education he had received and the beliefs he had adopted. Like exclusiveness and self-righteousness will always produce like re sults. Intolerance is its natural off-spring and when ever occasion may arise, it will not scruple at open violence. This has often been illustrated in the history of the people of God. Romish intolerance and persecution of dissenting believers, and Christian intolerance and persecution of the Jews, are but the outgrowth of the Pharisaic spirit. The Christianity of such bigotry is but a dead formalism, as destitute of the spirit of piety and as offensive to God as the dead carcass is destitute of life and offensive to us.

With respect to Saul’s Phariseeism as thus developed into open hostility to the cause of Christ it must be admitted that it was honest. The Saviour repeatedly characterized the Pharisees as hypocrites, mere pretenders to piety. But while this was true of them as a class, it cannot be doubted that there were sincere and devout individuals among them. Such was Nicodemus, who came to Jesus by night, and who afterwards became his disciple. Such, too, we believe, was Gamaliel, Saul’s instructor. His disinterested intervention in behalf of the church in Jerusalem and his wise counsels mark him as a man of just, upright and elevated spirit. The same was no doubt true of others. With respect to Saul there is not the slightest shadow of an imputation of insincerety or dishonesty resting upon him. The creed of Phariseeism was not with him a merely speculative theory. It was to him the truth of God. His intellect accepted it and endorsed it, his yearning heart received and loved it; his life consistently illustrated it. In the practice of its precepts and the observance of its ritualism, and in pushing it to the extreme of persecuting the fol lowers of Jesus, he verily believed that he was doing God service and would thereby win a place in heaven.

It is not surprising that it was such a vital force within him. Strongly “rooted and grounded” in his intellect, it touched, quickened and energized his moral sensibilities and moved and controlled his will. It leavened the entire man. He was its incarnation. His life was an accurate and comprehensive exposition of its spirit and principles. He tells us that as touching the righteousness of the law he was blameless. There had been no wilful neglect of any duty or demand of the law so far as outward observance was concerned. Every injunction and every prohibition, moral and ceremonial, as he understood it, had been faithfully observed. How potential must have been his faith, and how comprehensive and complete his obedience. Phariseeism had done its utmost; Saul is the highest expression and the best product of its moral and spiritual power.

But the very best that Phariseeism could do falls far short of the soul’s deliverance from sin and ultimate safety. “I say unto you, That except your righteousness shall exceed the righteousness of the Scribes and Pharisees, ye shall in no case enter into the kingdom of heaven.” The most perfect Pharisee is outside the kingdom, and if he never gets beyond Phariseeism he is lost forever.

Sincerity is not salvation. Saul followed the convictions of both judgment and conscience. Yet he afterwards learned that he was terribly wrong. A man may be perfectly sincere in believing a lie. It is truth, not falsehood, that saves. The God of truth could never put such honor on falsehood.

Faith is not salvation. Saul believed a great deal of truth, revealed truth. He believed it heartily and practiced it conscientiously. But it was not saving truth. He had a mighty faith, as his devotion proved. But he refused to believe, and hated and persecuted those who did believe, the only truth that can save the sinner.

Morality is not salvation. “All these (commandments) have I kept from my youth up,” said the young man. “One thing thou lackest,” replied the Master. “Touching the righteousness which is in the law, blameless,” is Saul’s record. No external obedience could be more complete, no life from a legal standpoint could be more irreproachable. Yet as he looks back upon that life in after years, he calls himself the chief of sinners and is filled with wonder at the grace that could forgive and save him. All his morality he counted but loss.

(Continue to: Saul, the Christian Convert)