Editor’s note: The following comprises Chapter 3 of Chivalry, by F. Warre Cornish (published 1901). Original footnotes are abridged.

(Continued from Part 2)

The education of a knight began at an early age. It appears from authorities of the 14th century that boys of noble birth were commonly left under the charge of their mothers till the age of seven. After that age it was the custom to send them to the care of some nobleman or churchman to receive knightly breeding among the squires and pages who served him.[1]

Personal service was the custom of chivalry, and lay at the foundation of all mediaeval institutions. It was no derogation to the dignity of a Prince Elector to bear the cup or wait at the stirrup of the Emperor; the Emperor himself held the bridle of the Pope. The Seneschal, Marshal, and Constable of the courts of Europe took their titles from acts of personal service, fragments of which continue among ourselves to this day in such observances as the maintenance of a cast of hawks by the Grand Falconer, the challenge of the Champion at the coronation, and till the end of the Stuart period the ceremonious dressing of the king at his levée, a custom which was carried to the extreme of etiquette at the French court. The niceties of court ceremonial did not, for the most part, survive the French Revolution; but they are still in force at Madrid, Berlin and Vienna; and every action of the Pope is regulated by traditional ceremony.

The imperial court of the king of the Franks became the model of other courts; and offices, all originally involving personal service, were multiplied. The lesser lords in their degree followed the custom of the king, not by way of imitation, but because it was natural to do so. The household of a feudal Seigneur was organised in the same manner as the court of a sovereign prince. Similar usages existed also in the religious houses, where the Abbot or Prior was served by the knights and gentlemen who held lands of him by feudal tenure, or were maintained in his service as mercenaries. The Abbot of St. Denys never moved from his Abbey without a Chamberlain and a Marshal, whose offices (as well as that of the Butler) were held as fiefs, and could, no doubt be transferred and transmitted like any other property.

Personal service was symbolical of the obligation to serve in war, which was the principal characteristic of feudal land tenure: the vassal was bound to serve his lord in the field, he might also be called upon to serve at home; in return for domestic service the lord gave his dependant board and lodging and the advantage of sharing in his opportunities of military distinction and royal or princely favour. No money wage was needed in a state of society in which all the wants of ordinary life were provided at home; but the attendants of the lord received his largesse, and got their share of his plunder in public or private war. It is not to be supposed that the many landowners who held of an overlord habitually lived at his court; they had their own manor houses and granges to live in, and their own estates to govern; and none but the greatest lords cared to have a number of idle gentlemen hanging about and making trouble with neighbours. Nor did the lord reside at one house only, nor in the principal fortress, except in time of danger. The term ‘castle’ includes country houses great and small. ‘The mediaeval baron removed from one to another of his castles with a train of servants and baggage, his chaplains and accountants, steward and carvers, servers, cupbearers, clerks, squires, yeomen, grooms and pages, chamberlain, treasurer, and even chancellor.’ Till the 17th century, if not later, not only the king, but his principal barons also, lived from house to house, carrying with them not only plate and personal baggage, but also beds, chairs, hangings and bedding. Purveyance and the rights and customs which attended it made the residence of the court burdensome to the neighbourhood, and caused courts to be frequently shifted.

The custom of holding court (tenir cour) extended from the king downwards to all whose wealth or dignity allowed it, and such courts were centres of chivalry wherever they existed. If they were less conspicuous in England than in other countries, it was because the English kings after the Conquest never allowed earldoms to be set up in rivalry to their own power. The feudal system (as Freeman taught us with exaggerated emphasis), was never established in England so completely as in France and Germany. Technically, all land was held by military tenure, and all law was subject to the King’s law. But the military service did not represent the whole value of the land: much land was undervalued by ‘beneficial hidation,'[2] much was held by ancient English usage; and the customs attaching to it were respected by the King’s judges, who preferred common law to royal ordinance; and in fact hampered legislation in the interest of custom. The freeholder was obscured but not abolished by feudal usages or fictions. English life was founded on a state of peace, not of war.

The feudal institutions, as brought into England by William I, and developed in the following century, gave more direct power to the king than was the case on the Continent, where (for instance) the Duke of Normandy was little less than an independent sovereign, owning only a formal allegiance to the King of France, his suzerain, and himself the uneasy lord of turbulent barons. Hence it resulted that great houses in England were courts of lords, not of princes; the bond of lord and vassal was not so close; the great barons were less magnificent; and the colour of English chivalry was of a soberer hue than on the Continent, where peers of France and German barons were constantly engaged in private war, and the chances of military distinction were consequently more frequent; whilst the passage of troubadours from court to court, the greater prominence of tournaments, the excitement of border warfare, and proximity to the great events and personages of the time, gave a splendour and gaiety to chivalry which could be matched in England only by the court of the king himself.

Among the incidents of service, besides the obligation to take the field under the lord’s banner, were various personal duties, rendered as the acknowledgment of land tenure, and covered by the same term, militare, which in mediaeval Latin is equivalent to the English ‘serve’ and ‘service.’ The requirements of the lord did not stop at the obligation of serving in arms for a certain number of days, and the daily offices of his personal attendants. They included also rights connected with the mill, the pigeon house, the culti- vation of the demesne, the administration of justice, and .the supply of the castle with food, firewood, and all that was required for daily use ; and fiefs were held on condition of discharging these services. It is one of the characteristics of mediaeval life that mutual offices were arranged, not accord- ing to the conveniences of the parties, but according to their rights. The history of feudalism, in small and great matters, it is to a large extent a history not of interests but of rights.

We may notice in passing that no feudal lord, from the king downwards, could rid himself of an inconvenient domestic or vassal, so long as he performed his feudal duty. Indeed the idea of free contract according to money payment, apart from all considerations of right or sentiment, is entirely modern. This security of tenure must have caused much inconvenience and trial of temper. We are reminded of Sanch Panza and his physician, without whose leave he might not taste of any of the dishes set before him; of the King of Spain who was roasted to death because the officer who had the right to move the king’s chair was not present; of the Queen of Spain who was dragged by the stirrup because no one dared to touch her sacred person. The lord might whip his fool or pull his coat over his ears, if his jests were inconvenient; but he could not secure himself against the repetition of the offence, and the laugh was always on the fool’s side.

Akin to ceremony, and of a wasteful and vexatious character, was the rule of perquisites. The king’s champion had the cup of gold out of which he pledged the king at his coronation. The robes, chair, cushion and other furniture of a knight of the Garter at his installation were till this century the perquisites of Garter and the Dean and canons of Windsor; and Dugdale gravely records a squabble between himself, as Garter, and the Dean, for the possession of the hassock on which a new knight had knelt. When the Frankish noble visited the Emperor at Constantinople, he dropped his mantle on the Emperor’s coming into the audience chamber, and it became the perquisite of one of the attendants. All the furniture of a death-chamber went to the servants; and the body of Edward III was left with hardly enough to cover it. The horses and armour of knights defeated in the jousts belonged to the victor, and were given to him and his squires.

As fiefs passed by heredity though this was no part of the original institution the offices also became hereditary; and in the decay of feudalism such offices as those of Great Chamberlain, Grand Falconer, Earl Marshal, Champion, were retained as hereditary property in families, apart from the lands to which they had been formerly attached.

Among the officers, great and small, of a lord’s castle was the Seneschal or majordomo (Senescallus, Dapifer). As with the great offices of state, the original meaning of this became obsolete, though the privileges remained. Thus the Elector Palatine was always Seneschal (Truchsess) of the Empire; the Count of Anjou, of France; the Sieur de Joinville, of Champagne; and the office carried with it lands and ‘Franchise’ or legal jurisdiction.

Other officers were the Master of the Horse, or Marshal,[3] the chief huntsman and chief falconer, besides the inferior domestics, such as butler, pantler, manciple, clerk of the kitchen, and the menial servants. These services were rendered by nobles at the king’s court, and in the houses of great lords, lay and clerical, they were places of more or less dignity. The household of a noble was self-supporting and independent of external help to a degree which it is difficult to conceive in days of easy supplies and rapid communication. A Roman noble’s villa with its array of slaves was managed in somewhat the same way; but the idea of noble service was unknown to the ancients.

A great house had its own cornlands and pasture, its stacks of corn and hay, granaries and storehouses of all kinds, mills, cattle byres, slaughter-houses and salting-sheds; if the cloth which the household wore was not woven at home, at least the sheep were shorn there, and the wool went to be sold or exchanged for cloth at the nearest staple town. Wool was carded and spun, cloth woven.

A remnant of this custom may be seen in the great number of places which were given away or sold at court, down to the time when they were abolished by Burke’s bill of 1782. The same thing may be observed in foreign courts; the smallest German prince maintained scores of useless retainers, body guards, masters of the ceremonies and their deputies, chamberlains, ushers, lacqueys, cooks, running footmen, huntsmen, musicians. All this was in the spirit of the Middle Ages. We read of Valez trenchans (carvers), valez servans de vin, servans de l’escuelle, valets de porte, etc., some of them boys and youths serving their apprenticeship for chivalry as wards of their lord, or sent by their parents to be trained with companions of their own age and condition.

The whole society of masters and servants dined and supped in the hall, and slept within the walls. Whatever was not of home manufacture was conveyed from the wood, the quarry, or the town by pack-horses and barges, or bought from itinerant chapmen, or at the fairs held at every large market town yearly or oftener, to some of which foreign merchants repaired from the Hanse towns, the Netherlands, Germany, France and Italy. Here were bought spices, iron goods, salt, silks, and furs, Flemish cloth, Spanish and French wine, and any other goods which could not be manufactured on the spot or bought in the towns of England.

It appears from the accounts kept in household books, many of which have been preserved, that the everyday life led in mediaeval castles, monasteries, and manor houses, was organised in a multitude of departments, each presided over by its own officers and worked by its own staff; the buttery, the kitchen, the napery, the pantry, the chandlery, and so forth. According to the scale of the house, some of these officers would be gentlemen, some servants. The master of the meals in King Arthur’s hall was Sir Kay or Keus, one of the knights of the Round Table. This is fable, but in agreement with fact. No kind of service was ignoble in itself; but the service of the hall, the armoury, the tilt-yard, the stable, the park and all that concerned hunting and hawking was eminently noble.

Enough has been said to show that a wealthy nobleman had within the walls of his own dwelling as much of the comforts and luxuries of life, as they were then understood, as would make it a desirable place of sojourn for those who by birth or choice were his dependents.

Apart from the providing of things of daily use, the lord’s house was also a place of leisure and amusement. All that concerned the sports of the field, the stable and the tilt-yard, was a matter of closer interest to knights and squires, and in some degree to ladies also, than the provision of material necessaries, food, drink, clothing, and marketable goods.

It was the custom in the Middle Ages, as in Imperial Rome, to multiply services and servants in order to enhance the dignity of their master. At a time when intercourse with foreign countries was difficult, and the taste for spending did not find easy satisfaction, whilst at the same time much wealth, the produce of agriculture and grazing, was often accumulated in a single hand, rich men did not know what to do with their substance. They amassed great store of gold and silver plate, jewels, furs and precious raiment. Sir John Arundel, who was drowned in 1380, lost ‘not only his life but all his apparel to his body,’ fifty-two suits of gold. The Black Prince left an immense treasure of gold and silver, plate and jewels, besides rich beds and their furniture, cloth of arras embroidered with ‘mermyns de mer,’ swans, eagles, and griffins; ‘grand tresor, draps, chivalx, argent et or’: the household stuff of Piers Gaveston is on a like scale and mediaeval wills, of which a large number are extant, resemble in their degree that of the Black Prince.

The most obvious and the least invidious form of expenditure was in keeping house. Hospitality was set high among social virtues, as it is in all rude societies. There is much talk of eating and drinking in fabliaux and romans. An English lord kept open house all the year round; as the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of Durham did within the memory of man. The feasts of kings and great prelates were incredibly extravagant. Richard Earl of Cornwall is said to have entertained 30,000 guests at his marriage; if we divide the number by ten, it is still large. Variety of fare was afforded by the wide tracts of moorland, forest, and fen, in which game of every kind was plentiful, from red deer and wild swine to coneys, from cranes and swans to larks. Droves of oxen, sheep and swine, thousands of wild fowl, deer, and roebuck, salmon, pike and carp, were slaughtered for these festivities, conduits ran with wine, and innumerable hogsheads of beer were broached.

Among the chief glories of a rich man was to be able to shew a great number of retainers wearing his coats and living at his expense; and thus the castle swarmed with idle hangers-on, Will Wimbles and Caleb Balderstones, glad to earn their keep by performing light duties about the stable and the armoury. The abuse of ‘livery'[4] had to be met by legislation, and was only put down by the despotic rule of Edward IV and Henry VII. ‘The baron could not reign as king in his castle, but he could make his castle as strong and splendid as he chose; he could not demand the military services of his vassals for private war, but he could, if he chose to pay for it, support a vast household of men armed and liveried as servants, a retinue of pomp and splendour, but ready for any opportunity of disturbance.’

Here came in the personal service of the knights, squires, and pages who ate at the lord’s table. It is not to be supposed that knights attended to their own arms and horses; it was enough for them to see that their accoutrements and those of their lords were kept in good trim by the squires and the army of grooms and helpers employed in the castle.

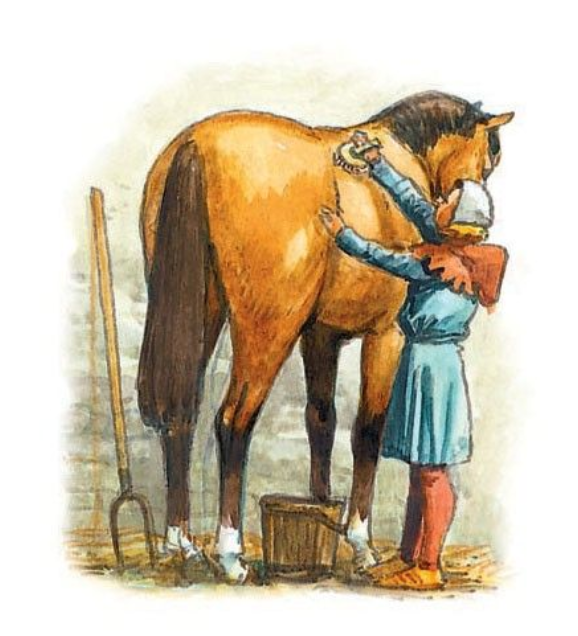

The son of a knight or gentleman who was thus sent to school was during his apprenticeship known as a page[5] or henchman,[6] and was under the orders of a squire called the Master of the henchmen. The apprenticeship began at an early age, so soon the boy was removed from the care of ‘nourrices et gouvernantes,’ perhaps at the age of seven, and lasted seven years, during which time he lived much with the ladies, but was also learning the business of a squire in the stable, the armoury, the kennels and hawk-pens, and the hall. At the age of 14 the boy was old enough to wear a collar of SS and be entitled squire.

Pages waited at table, as choristers nowadays wait in the Halls at Winchester, Oxford and Cambridge. The institution of fagging in our public schools is a relic of mediaeval service: and till some thirty years ago junior scholars under the title of ‘servitor’ waited on their seniors in Hall at Eton and took their own dinner in true mediaeval fashion when their masters had done. Philip the Hardy, son of John the Good, King of France, waited on his father during his captivity. Joinville, being a great lord, carved for the King of Navarre in the hall of Lewis IX as a squire, ‘for I had not yet put on the hauberk,’ i.e. had not received the honour of knighthood; and he tells how he himself took in the son of a poor crusader, and brought him up in his own house.

The pages, henchmen or damoiseaux (domiselli) also called varlets (valeti or vallecti, vasseletti, young vassals) were chiefly boys of noble or knightly birth, brought to the castle to learn ‘courtesy’ (curialitas) i.e. the breeding learnt at the court (curia) of a prince or noble. ‘Exemplar morum domibus procedit eorum,’ says Walter Map (1150). From the highest ranks to the lowest degrees of gentry this was the custom. Innumerable instances might be given, both historical and from the notices in literature. To take a few — Stephen of Blois, afterwards King of England, was nurtured by his uncle Henry I. Malcolm King of Scots was brought up at the court of Henry II. Henry II himself lived at Bristol in the house of his uncle Robert Earl of Gloucester, who appointed a clerk, Master Matthew, as his governor. Henry VI was put under the care of Richard Beauchamp Earl of Warwick, and the heirs of baronies in the crown’s wardship were brought up with him (as was the common practice in the king’s court); so that his court became ‘an academy (gymnasium) for the young nobility.’ Fulk Fitz Warren was brought up at the court of Henry II to be companion to his boys. We are not surprised to hear that John quarrelled with him, and when Fulk kicked the prince in the chest (‘en my le pys’) made complaint to his father; who (we are glad to learn) ‘apela son mestre e ly fest batre fyrement e bien pur sa pleynte’; for which John hated him ever after, and took away his lands. Thereupon Fulk ‘s’en parti de la court e vynt à son hostel,’ taking to the woods afterwards, and making free with the king’s men and merchants who did business with them.

The same practice was followed by the owners of castles and great houses spiritual and secular, both in England and in other countries. Jean de Saintre was brought up at the Hotel of the Seigneur de Preuilli, and passed thence to the court of King John the Good. Montaigne (iii. 175) says ‘ C’est un bel usage de notre nation, qu’aus bonnes maisons nos enfans soient regeus pour y etre nourris et élevés pages comme en une eschole de noblesse.’ Froissart gives a lively picture ot the Court of the Count of Foix. ‘On veoit en la salle, en la chambre, en la cour, chevaliers et escuyers d’honneur, aller et marcher, et les oyoit-on parler d’armes et d’amour; tout honneur étoit là-dedans trouvé: toute novelle, de quelque pays ne de quelque pays ne de quelque royaulme que ce fust, là-dedans on y aprenoit; car de tout pays, pour la vaillance du seigneur, elles y venoient.’

Bishops and abbots were served in the same way by noble youths sent to them by their parents or guardians, as well as by the young clerks whom they brought up to become chaplains, scholars and churchmen. Fitz Stephen, the biographer of St. Thomas of Canterbury, says, ‘the nobles of the realm of England and of neighbouring kingdoms used to send their sons to serve the Chancellor (Thomas), whom he trained with honourable bringing up and learning; and when they had received the knight’s belt,[7] sent them back with honour to their fathers.’ Thomas himself had been educated in the palace of Archbishop Theobald. Roger of Hoveden (writing about 1180) tells us that William Longchamps, Bishop of Ely, was served by the sons of nobles (filios nobilium procerum regni… secum habuit domisellos [damoiseaux]). Robert Grosteste Bishop of Lincoln (circ. 1220) said that he himself, though of humble birth, had learnt courtesy ‘in domo seu hospitio majorum regum quam sit rex Angliae,’ meaning thereby David and Solomon. Among those whom Grosteste himself nurtured were Henry and Almeric de Montfort, the sons of Earl Simon. Richard, the son of Henry I was festive nutritus by Robert Bloett, Bishop of Lincoln (1094-1123).

This practice continued throughout the Middle ages. Robert Whiting, the last abbot of Glastonbury, Cardinal Morton (among whose pages was Sir Thomas More) kept it up, and there was ‘a mess of the young lords’ at Wolsey’s table; among them the eldest son of the Earl of Northumberland. The Duke of Norfolk and the Earl of Northampton at the same date were both ‘bred as pages with bishops.’ The chevalier Bayard was page to his uncle the Bishop of Grenoble, and served as his cupbearer when he dined with the Duke of Savoy. Some boys were brought up at home; Ordericus Vitalis (circ. 1100) for instance, whose master was Siward, a noble priest. Gaston de Foix served his father with all the meats, tasting each first himself. Chaucer’s squire was

‘curteys… lowly and servisable,

And carf before his fadur at the table.'[8]

Besides the schools attached to cathedrals, religious houses and the palaces of bishops and abbots, literature was not wholly neglected by the secular lords who received boys into their houses. To read and write, to play the harp and sing were part of a knight’s accomplishment, and there were unbeneficed clerks and needy troubadours who were glad to get some teaching to do. The ladies of the castle also took interest in the boys who came to be instructed, teaching them letters, the games of chess and tables, the rules of good manners, and the rudiments of gallantry.

We may set against Scott’s

Thanks to St. Bolhan, son of mine,

Save Gawain, ne’er could pen a line [9]

another couplet;—

Mon filz si est bien letrez,

et en touz livres bien lisanz.

Robert I of France was ‘very learned in humane letters.’ Henry Beauclerc, according to Freeman, knew Greek.[10] Galbert tells us that Charles the Good, Count of Flanders, was reading his prayers in church when he was murdered (1124). Though Du Guesclin would not learn to read and write, it was not for want of opportunities. Garin le Loherain in the romance could read (‘de letres sot’.)

It is not to be supposed that the kings and ecclesiastics who made their mark on a piece of parchment were always illiterate. The seal was what gave a document validity; the mark was evidence of the personal presence of the witnesses (signando affuerunt.)[11] Lords and ladies, and particularly the latter, could read and write. Those who had no learning could do without it, in a time when the chief part of every kind of business was discharged by word of mouth.

The knight in the romance says—

Bele, nous nous entramions

Quant à l’escole aprenions;

L’uns à l’autre son bon disoit

En Latin, nus ne l’entendoit. [12]

If Latin was little studied except by clerks, French was for some centuries after the Conquest the language of the court, or at least was the common language of the court, and was a subject of teaching. The stock of books in a great house was very small. Humphrey Duke of Gloucester, the founder of the University Library at Oxford, and a great lover of books, had some 200.[13] Books were rare and expensive; but the growth of a manuscript literature of a popular kind is some proof of a reading public. School teaching was oral, and the only book possessed by the scholar was his copy of the lesson written by his own hand. Learning by heart formed a principal part of education; poetry, manuals of history, grammar and heraldry were committed to memory. The common manual of good manners which all young people studied was a Latin treatise called ‘Stans puer ad mensam‘ ascribed to Robert Grosteste Bishop of Lincoln, which was translated into French and English.

The principal part of a boy’s education, however, was carried on out of doors. All kinds of exercises and games were practised, such as wrestling, boxing, running, riding, tilting at the ring and the quintain; and such amusements as bull and bear-baiting. The squires who had charge of the pages or henchmen were required to ‘lerne them to ryde clenely and surely, to draw them also to justes, to lerne them were their harness, to have all curtesy in wordes, dedes and degrees… moreover to teche them sondry languages and other lerninges vertuous, to harping, to pipe, sing, dance… with corrections in their chambers.’ These ‘corrections’ were an important part of the training, and the life of a scholar was full of hardship. In Henry VI’s deed of appointment of his nurse Dame Alice Butler is a proviso that she is to have power ‘to chastise us reasonably from time to time.’

The name of squire, (scutarius, escuyer, armiger) was given both to gentlemen attendant on a knight who aimed at no higher grade of chivalry, and to youths, the sons of knights and to be knights in their turn, who came to learn the business of arms and courtesy from their seniors. The chief part of the service was discharged by the squires, old and young, and pages; who had under them grooms, huntsmen, and domestic menials. The squires (as we have seen) carved in Hall; they also handed vessels of plate and served wine, followed by the varlets or pages bearing the dishes. They gave water for the guests’ hands after dinner:—

Apres le manger laverent;

Escuier de l’eve (eau) donerent;

they made the beds for their lords,

Les lits firent li escuier;

Si coucha chacuns son seignor;

helped them to dress;

Si e dozel (damoiseaux) l’ainderain gen à vestir;

groomed the horses and saw to the armour. The Squire brought his lord the sleeping draught (vin de coucher) of piment or clairet; slept in his chamber if he desired it, or at the door; a custom which continued as late as the times of the Stuarts.

The Squire was to serve his knight in everything; to arm him for the tourney or the battle, and to see that all his arms and accoutrements were in perfect condition; to be up early and late, and never consider his own convenience. In the tournament the squire had to provide his ‘master’ with fresh lances, and to hold the horses and keep them for fighting, and to take part in the mêlée. In battle the two squires who attended a knight fought at his side and supplied him at need with fresh arms or horses.[14]

Among the services required of damoiseaux and squires was that of waiting on the ladies in the castle; and this service was no less honourable than that rendered to their lords. They played chess in the ladies’ bowers, walked with them in the garden, rode hunting and hawking with them; and scandal was not unfrequently caused, justly or unjustly, by the freedom of intercourse which mediaeval manners allowed.

When the page had passed to the condition of squire, and had there learnt all knightly duties — no easy education, for squires were hard upon pages, and knights upon squires — he might aspire to the dignity of knighthood, if he could approve himself worthy. Squires were as eager as their lords for opportunities of distinction in tournaments or in war, and it was not every squire that could hope to take up knighthood. Knighthood indeed was a costly burden, and the poor gentleman had to content himself with the lower grade of chivalry. This fact is recognised in our institutions by the computation of a knight’s fee at twenty pounds a year in landed property. Many squires, therefore, though of noble blood and in other respects fit to take up knighthood, were content with the lower condition, and never assumed the honours and responsibilities of knighthood.

(Continue to Part 4)

______________________________________________________________

[1] The origin of this custom may probably be traced to a time when the suzerain took possession of the sons of his vassals as hostages for their fathers’ fidelity. Martin, Hist. de France, iii. 336.

Me fist avoir en ostage,

Ij vallez de noble lignage.

Roman de Rou.

[2] i.e., rated below its value.

[3] Mar-schalk = horse-servant.

[4] Livery (liberatura) properly means ‘allowance.’ A certain amount of cloth was served out anually to each member of the household in his degree. Within the present century (for instance) the Provost, fellows, scholars and servants of Eton College had their ‘livery’ measured, cut and delivered to them every year by the Bursar; 20 yards for the Provost, 10 for each fellow, and so on. There were similar ‘allowances’ of beer, bread, ‘bavin and billet’ for firing, etc.

[5] Page from paedagogium, a training-school: pagii, paedagogarii (Ducange.)

[6] Henchman. Henchman = haunch-man.

[7] i.e. gone through the stages of page and squire. See Furnivall. “Forewords” E.E.T.S., 1867).

[8] Canterbury Tales: Prologue.

[9] Marmion, vi. 15.

[10] This surprising statement rests upon the authority of Marie de France, who (according to one reading of the text) speaks of “li rois Henris” as having translated Aesop into English. She probably means Henry III, who was her contemporary, and who, though there is no reason to suppose that he knew Greek, had men about him who did, such as Grosteste and his protégé John of Basingstoke, the pupil of Roger Bacon, Freeman. Wm. Rufus Vol. IV., Appx. EE.

[11] It is hardly worth mentioning that the expression ‘to sign’ is properly ‘to seal’. In the library of Eton College is a deed signed by William II with a cross, and sealed with the Great Seal ‘Rex Guillelmus Regis Guillelmi filius coram baronibus suis sigillo suo firmavit.’ The crosses of the barons and prelates follow that of the king; the names are added by the clerk.

[12] This must have been like Lucentio’s wooing in the Taming of the Shrew.

[13] Duke Humphrey gave 129 books to Oxford, three of which are now in the Bodleian, and some few more in various colleges, the British Museum, and at Paris.

[14] destrier (dextrarius) is the warhorse led by the squire on his right.