Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Heroes of the Indian Empire, by Ernest Foster (published 1886).

Turning to another quarter of the Empire, let us now see what part in this gigantic struggle had meanwhile been played by Sir Henry Lawrence.

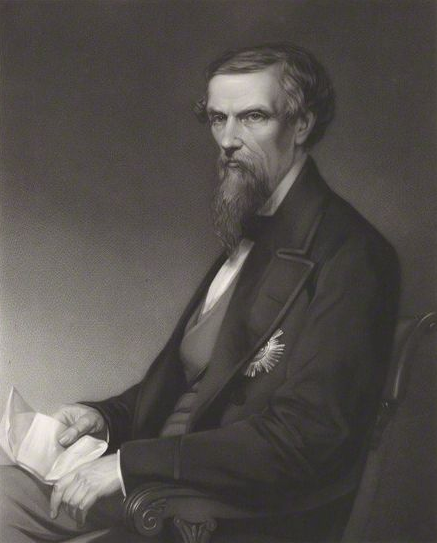

At the moment when the Mutiny was on the point of breaking out—in March—Sir Henry had been appointed to succeed Mr. Jackson as Chief Commissioner of Oude. The Governor-General had come to realise that affairs in that province were rapidly drifting from bad to worse; and for the task of removing the discontent and difficulties which were accumulating there, he selected a man peculiarly fitted to undertake it. For Sir Henry Lawrence, an elder brother of Sir John, was one of the most distinguished officers in the Indian service. As a boy of sixteen, when, in 1823, he became an artillery cadet in the Company’s army, he won golden opinions from those in authority over him; as he grew older he rapidly acquired reputation alike for ability, intelligence, and high-mindedness; and after serving his country in various ways, first in Burmah, afterwards in Afghanistan, and next in a civil capacity in the Sikh War, he was appointed to the important position of British Resident at Lahore. This post he filled for two years with great distinction, when ill health compelled him to visit England. Returning in 1849 he again resumed his duties in Lahore, though not as Resident, for the Punjab had recently become British territory, and its affairs were to be administered by a new Board, of which he was to be the President. We have already seen what wonders were performed in the newly annexed province during the few years that Sir Henry and his brother John laboured together there; and it was at the end of this period, when the latter was made Chief Commissioner, that Sir Henry parted from him to become the British representative in the States of Rajpootana. Here he laboured for four years more; and he was on the point of again embarking for Europe on account of his health, when, at the pressing request of the Governor-General, he proceeded to Lucknow, the capital, to assume the Chief Commissionership of Oude.

As events soon proved, however, this appointment was made too late. Sir Henry’s predecessor, instead of having conciliated the people of Oude, had alienated them; when the new Commissioner reached Lucknow he found, says Sir John Kaye, “that almost everything that ought not to have been done had been done, and that what ought to have been first done had not been done at all, and that the seeds of rebellion had been sown broadcast over the land;” while to crown all, the city was filled with thousands of starving soldiers and retainers of the deposed king.

Sir Henry at once perceived that a crisis was at hand; and he lost no time in coping with the difficulty. Directly after his arrival he set to work to repair the errors of the past, by redressing grievances, by paying delayed pensions, and by showing every courtesy to the native princes and nobles.

But as day by day passed, signs of coming revolt grew more ominous; and it was soon plain that all his efforts to restore confidence would be unavailing. While keeping up an appearance of unconcern, Sir Henry therefore began to make preparations for the siege which seemed to be inevitable; and having turned the Residency into an extemporised fort, well stored with provisions and ammunition, he awaited the storm.

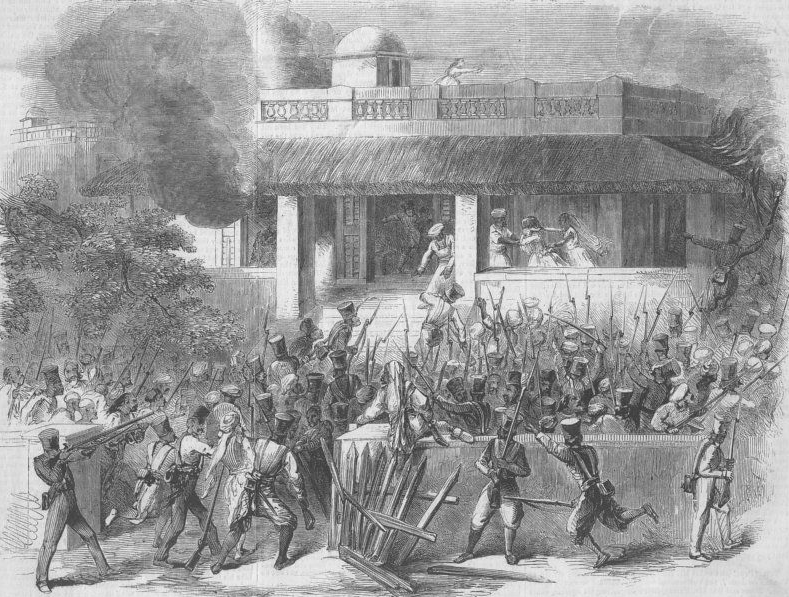

Nor had he long to wait. When on the 3rd of May the first attempt at mutiny occurred, he suppressed it in a masterly manner; but by the 30th five of the Sepoy regiments in the garrison had broken out, and the firing by them of the cantonments, accompanied by the murder of the officers, was the signal for a general rising. Then followed scenes of bloodshed and massacre in different parts of Oude; and before the end of June, not only the capital, but the whole province, was in open rebellion.

Up to this time Sir Henry had maintained his hold on Lucknow and the neighbourhood; but the 30th of June was the last day on which he was able to do so. For on that morning, in attempting to carry out a bold venture, most disastrous consequences ensued. But to better understand the situation, and so that light may be thrown upon other events, to be referred to hereafter, let us glance for a moment at Cawnpore—a military station between Lucknow and Allahabad, and regarded as the “key of Oude”— which had just been the scene of terrible doings.

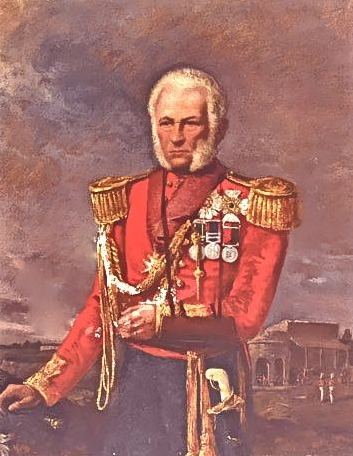

On the breaking out of the Mutiny, Cawnpore was garrisoned by 3,800 men, consisting of four regiments of Sepoys and a battery of British artillery; but, in all, General Sir Hugh Wheeler, the commandant, had only 200 European soldiers with him; while under his charge were both the European residents, and the families of the 32nd Regiment, then stationed at Lucknow. When in the month of May Sir Hugh perceived a rebellious spirit growing up around him he entrenched a spot about 200 yards square; and having stored this with provisions for a month, he prepared to withdraw into it, if necessary, with the Europeans who were about him. On the 5th of June the rising took place, when one after another the native regiments mutinied; and after plundering £170,000 from the treasury, taking with them horses, arms, and ammunition, opening the gaols, and firing the bungalows, they prepared to march to Delhi. But they did not proceed thither. Instead, they were induced to put themselves under the leadership of Nana Sahib, a miscreant who had been foremost among the conspirators against the British. This man, the son of a Brahmin, had been adopted by Bajee Rao, the Ex-Peshwa, or nominal head of the Mahrattas; and the chief reason of his hatred of the British was the refusal of the Indian Government to continue to him the pension of eight lacs of rupees (£80,000), which had been paid to Bajee Rao; though he was permitted to have a retinue of 200 soldiers, and a fortified palace at Bithoor, ten miles from Cawnpore. He had recently been journeying from station to station in the North-west Provinces, fomenting the spirit of rebellion among the Sepoy regiments; and it was when the mutinous troops were marching off to Delhi that he, for the first time, took open command. Then it was that he persuaded the Sepoys to return to Cawnpore, in order to attack the small British garrison there; and on their consenting he raised the Mahratta standard and hastened to the deadly work.

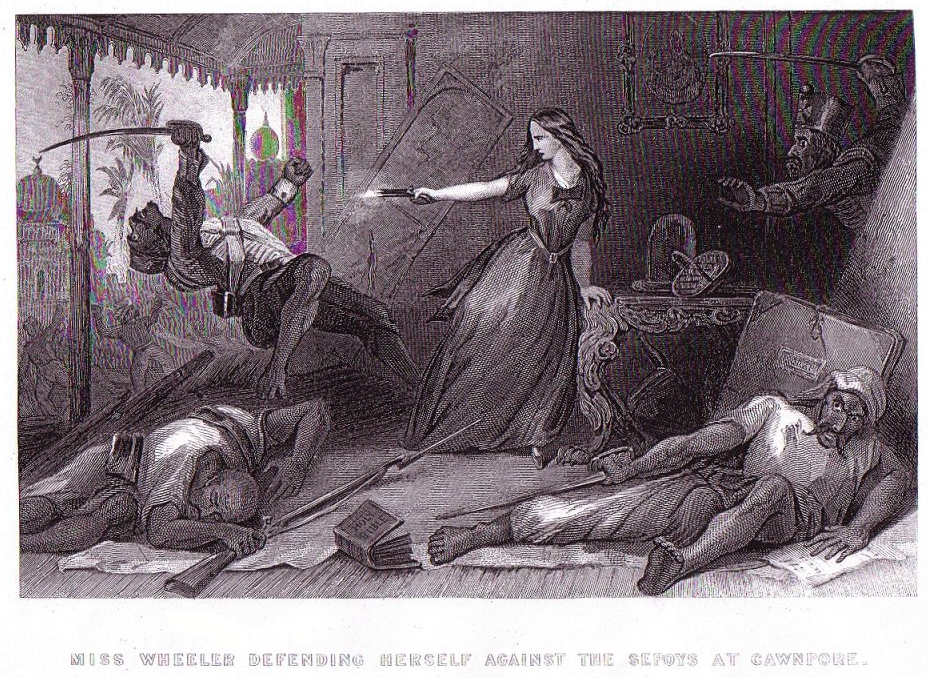

Sir Hugh Wheeler had by this time taken refuge in his fortified enclosure, and with him were about 900 Europeans, of whom more than two-thirds were women, children, and other non-combatants. Around this slender entrenchment the wild rebels now closed, and Nana Sahib’s force, increased hourly by the arrival of mutineers from Allahabad and other places, was soon at least ten times stronger than the garrison. The siege began on the 7th of June; and for three weeks, while shot and shell were incessantly poured into the fortification, and the hapless defenders suffered untold horrors and privations, it went on in all its fury.

But gallant though the defence, and nobly though all—not only men, but even gently nurtured ladies —laboured, it was of no avail; and when, on the 26th, Nana Sahib offered to allow Sir Hugh and his companions to proceed by the river to Allahabad, if they would surrender, the General, for the sake of the women and children, felt compelled to agree to the terms.

So on the faith of an oath taken by Nana Sahib upon the Ganges—the most solemn oath of a Hindoo —the capitulation was effected.

For the first time for twenty-one days the din of cannon, and of mortars, and of musketry now ceased; but little dreamed Sir Hugh and his noble comrades that the monster in whom they were trusting had three weeks before murdered in cold blood no fewer than 130 fugitives—men, women, and children —who had escaped from the mutineers at Futtygurh, and landed at Cawnpore; little, too, dreamed the brave women and the helpless children of what the morrow was to bring forth! On that terrible morning there was perpetrated one of the foulest deeds of treachery ever known.

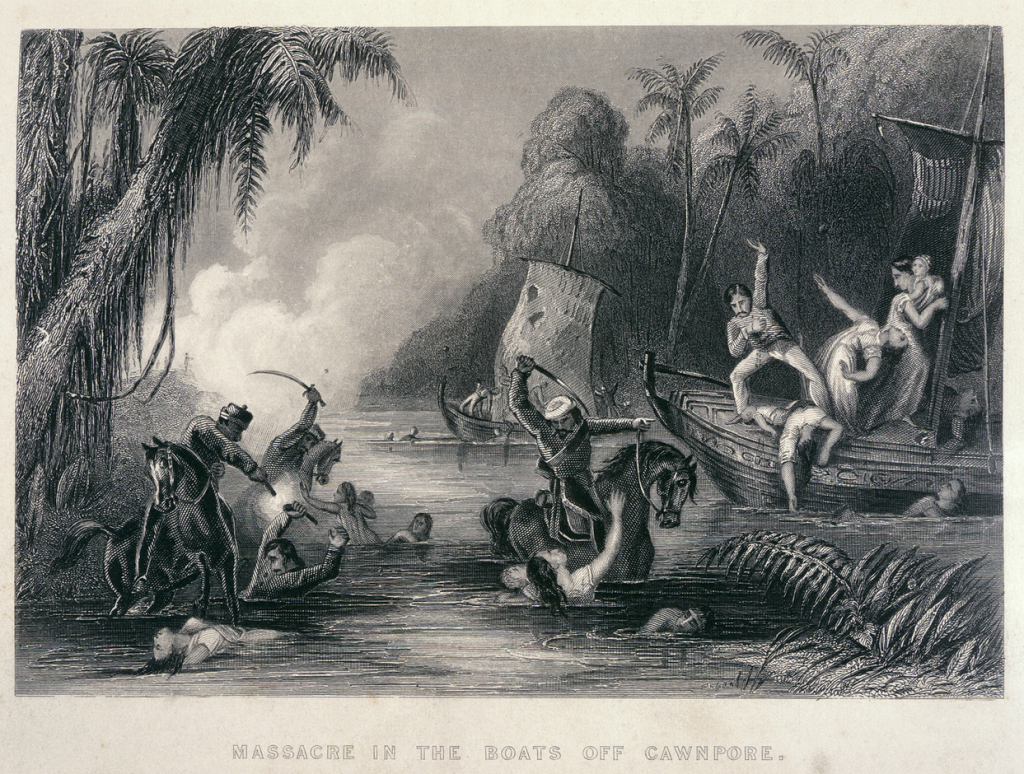

The surviving Europeans—many of them wounded and exhausted—had reached the riverside at about eight o’clock, and were permitted without molestation to enter the boats which they believed were to convey them to Allahabad. But no sooner had they embarked, than at a pre-arranged signal two cannon, which had been hidden, were immediately opened upon them; and then a murderous fire was showered down by the ferocious Sepoys, who lined both banks of the river. Thereupon we are told “the native boatmen deserted them at once, but a few of the boats escaped to the opposite bank. They were met there by Sepoys and by Oude cavalry, and all except One boat-load were seized. The men were either drowned, or shot in the river, or carried back before Nana Sahib, and massacred by these savages in his presence; while the women and the children (about 200 in number) were shut up for the present in one building. The boat that escaped struck upon a sand bank on the 28th. Sepoys, who had followed its course, constantly fired upon the passengers. Fourteen officers and soldiers fought them desperately, and got clean away; but they lost their road, and were obliged to take refuge in a temple. From their shelter they were smoked out. They then again fought the Sepoys, and five of them escaped to the Ganges. By hard swimming with the current four left their pursuers behind them, and at a distance of seven miles from the spot where they had taken the water they were rescued by the servants of a friendly rajah, and finally saved.” On the day after this ghastly massacre Nana Sahib caused himself, amid great ceremony, to be proclaimed Peshwa; and thus terminated the first—though alas! not the greatest— of the diabolical crimes with which the villain’s name is inseparably linked.

Leaving Nana Sahib for a brief time in triumphant possession of Cawnpore—holding in captivity the women and children whom he had carried off from the boats—let us return to Lucknow; after which we shall see how the infamies of which their countrymen had been the victims were avenged at the hands of Havelock, Outram, and Colin Campbell.

By their successes at Cawnpore, the mutineers were not only much encouraged, but numbers of them had now moved off in the direction of Lucknow; and it was on receiving news that bodies of rebels were marching upon the city that Sir Henry Lawrence determined, on the 30th of June, to present a bold front. He therefore led out a force to attack them; but unfortunately he did so without having accurate knowledge of their numbers. These proved to be several thousands, while his own men mustered only about 700, of whom half were Europeans, the rest faithful natives; and to add to his difficulties the native artillerymen, in whose loyalty he had trusted, having proved treacherous, cut the traces of their horses, threw the guns in a ditch, and rode away to join the mutineers. The gallant leader was therefore obliged to retreat, and it was with the loss of one-sixth of his men, as well as of “the reputation which had hitherto held the city in awe,” that he and his followers returned to Lucknow.

The rebels now advanced in thousands towards the city, to which they immediately laid siege; and it was on the same afternoon that Sir Henry and his garrison, numbering 1,692 (Europeans and loyal natives), besides about 350 Europeans, including women and children, shut themselves within the Residency, to begin a defence lasting four long months, which forms one of the most striking episodes of the Mutiny.

Sad to say, however, though it was solely to Sir Henry’s foresight that every preparation had been made to meet the worst emergencies—though it was by following his plan of operations that the besiegers, who scarcely ceased their assaults day or night, were kept at bay—it was not ordained that he should share in the triumph in which the defence at length culminated—the deliverance of the garrison at the hands of Havelock, Outram, and Colin Campbell. For on the second morning after the siege began, while in an exposed room of the Residency, where he was giving some instructions to a subordinate, a shell burst beside him, which shattered his thigh.

From this he never rallied, and after two days of intense suffering, during which he tried to forget his pain, so as to give directions for securing the safety of those who were around him, the gallant soldier breathed his last.

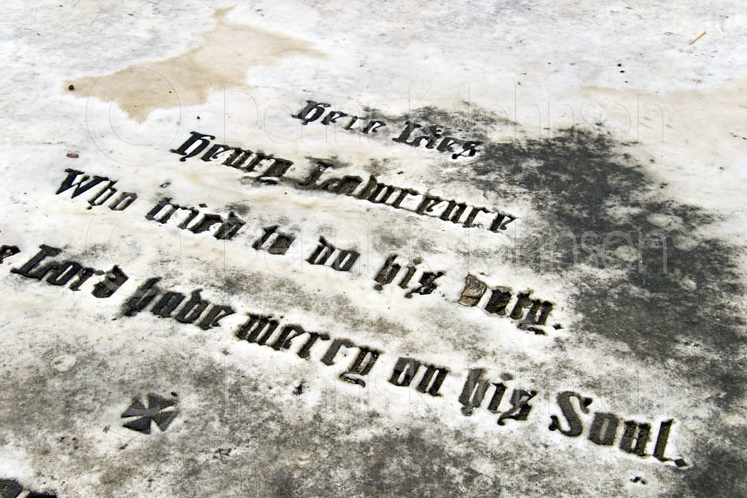

“Here lies Henry Lawrence, who tried to do his duty,” was the simple inscription which he himself wrote for his tomb. How he more than acted up to it during the whole of his career, his life and his death alike abundantly testify.

While the beleaguered garrison — mourning their dead chief, and keeping in remembrance one of his last injunctions, “Never give in!” — were repelling with unflinching courage the fearful storm of fire that now raged round them from day to day, and were cheerfully enduring inconceivable hardships, an Army of Relief was already marching towards Cawnpore and Lucknow; and to the story of its famous leaders and their achievements we will now turn.