Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Heroes of the Indian Empire, by Ernest Foster (published 1886).

Eighteen hundred and fifty seven will always be memorable in the annals of the East. In that year the great Sepoy Mutiny broke out, and over India swept the fiercest storm by which that land was ever shaken. For months and months the flag of rebellion was flaunted; for months and months fire and sword vied in deadly work; and at no period of its history had the Empire known darker days.

Without attempting to sketch more than a brief outline of this awful crisis, it is proposed to tell here of some of its more striking events, and particularly to speak of a few of the illustrious leaders who at this time of peril defended India from its foes.

First let us see how it was that in the midst of apparent content, and after nearly a century of British rule, the safety of the Empire came to be suddenly endangered. The real causes of the outbreak are not easy to state; but various reasons are assigned. To begin with, there can be no doubt that the rapid extension of British dominion—which in 1856 had culminated in the annexation of the great province of Oude—caused the natives to fear that ere long the Hindoo and Mahometan religion would be eventually abolished, and Christianity forcibly instituted; indeed, so deep did the conviction become, that they lent a willing ear to every rumour that appeared to confirm it. Then, evil-minded men took advantage of this credulity to spread abroad all kinds of false statements as to the intentions of the English. Among these was one to the effect that with the new Enfield rifles, about to be distributed to the army, cartridges greased with the fat of cows and pigs were to be used. It being necessary for the cartridge tops to be bitten off before they could be fired, the express object of their introduction, it was declared, was to cause the Sepoys to lose caste—the cow being sacred to the Hindoo[1] and the flesh of the swine forbidden to the Mahometan. As early as January, 1857, this report had gained currency. In that month, it is said that while a Sepoy of Brahmin (or the highest) caste, who was one of the rank and file of a Bengal infantry regiment, was at his meals, a Hindoo of low caste, passing by, asked him for a drink of water out of the vessel he had been using.

“I have just scoured it,” was his reply, adding, “and you would defile it by your touch.”

“You think much of your caste,” was the rejoinder, “but wait a little. The ‘Sahib logue’ (that is, the gentleman strangers, meaning the Indian officials) will make you bite cartridges steeped in cow and pork fat; then where will your caste be?”

About the same time a prediction made by astrologers was fully believed in, that in 1857 the Company’s raj, or rule, in India was to end. “The English had been the conquerors at the battle of Plassy a century before; but their doom was sealed by fate, and now there was no chance for them—they must lick the dust!” The Sepoys, too, had now realised their worth, and having begun to believe that to their valour the British owed their victories and conquests, and knowing, too, that the European forces in India had become much smaller, they thought that they held the destiny of the Empire in their own hands. Besides all this, discontent of another kind reigned in the newly-annexed province of Oude, owing to the unpopularity of Mr. Jackson, the British Chief Commissioner; while in Delhi, where the descendant of the old Mogul sovereigns was still permitted to reside, a strong feeling of animosity had been aroused by the threat of the Government to remove the so-called king to another part of India.

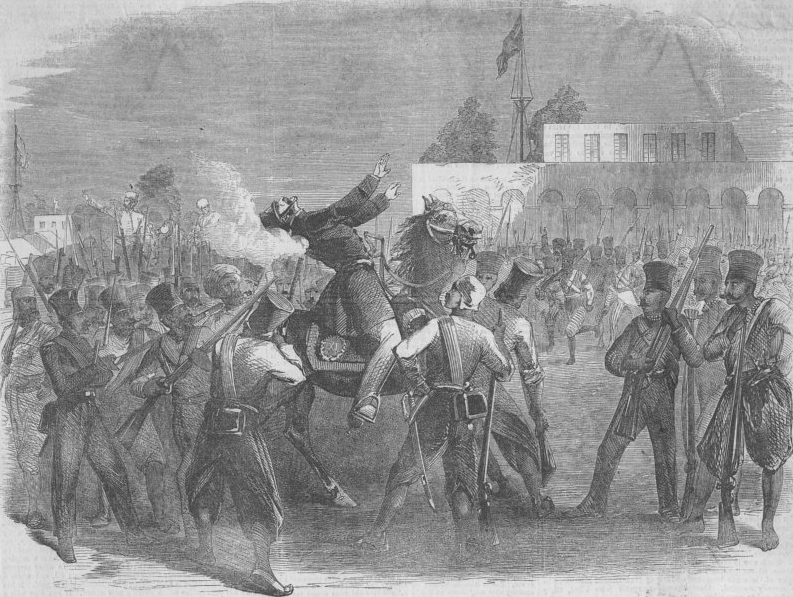

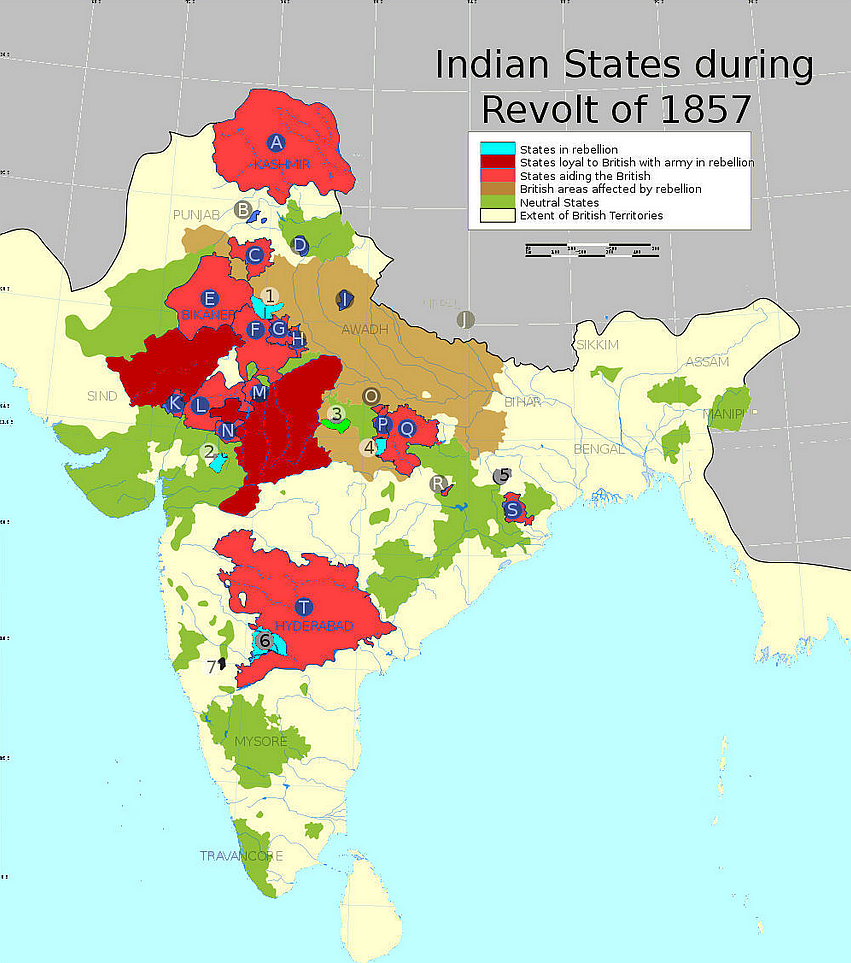

Such were a few of the causes of the revolt; and such was the condition of affairs at the beginning of 1857. Nor was it long before the blow was struck. Commencing with incendiary fires at Barrackpore in January—in spite of official assurances that there was no ground for alarm, that the stories about the greased cartridges, the designs on the native religion, and other rumours were utterly false— regiment after regiment of Sepoys in different parts of India speedily became disaffected; and by May the mutiny burst into furious flame. On the evening of Sunday, the 10th of that month, the first serious outbreak occurred at Meerut, where the Sepoys rose, shot their officers, and then after attacking every defenceless European they could find — irrespective of sex or of age—marched off to Delhi, forty miles distant. On their arrival there, all the Sepoys belonging to the garrison joined them, and then the terrible work of destruction and murder went on there too. Save a few who made their escape, the Europeans, including many ladies and children, were ruthlessly shot down; and the mutineers having taken possession of the city, proceeded to proclaim Bahadur Shah, the descendant of the Moguls, Sovereign of India. Meanwhile the insurrection, accompanied by similar atrocities, spread in every direction; and ere long thousands and thousands of Sepoys had deserted their colours and turned their arms against the British.

It was soon evident that Delhi would be the focus of the rebellion, and thither all eyes were now turned. The recovery of that city was vital to the safety of the Empire, for so long as such an important post remained in the possession of the mutineers no confidence in the British power could be restored, and India would be at the mercy of the enemy. But how was the task to be accomplished? Even with many thousands of men the recapture of this most formidable stronghold—whose walled defences measured seven miles in circumference—would be a gigantic undertaking; but at this juncture there were comparatively few European troops in India, and for these every day was bringing fresh calls from different parts of the Empire.

Undaunted, however, by the strength of the enemy —now daily increasing through the arrival of fresh bands of rebels—it was determined that as many troops as were available should be despatched with all speed to Delhi; and by the 8th of June a little army, consisting at first of only three regiments, which were subsequently joined by another detachment, had fought its way there, and after defeating a division of the enemy, had entrenched itself on the Ridge, a rising ground about two miles from the city. By this time there were some thousands of Sepoys in Delhi, and, although on the first appearance at the city gates of the mutineers from Meerut the great powder magazine had, at the sacrifice of nearly all their lives, been blown up by Lieutenant Willoughby, the officer in charge, and eight of his companions, their supply of arms and military stores from the British arsenal was boundless; and so all that this brave little body of “besiegers” could do was to defend their entrenchments, and await either reinforcements from Calcutta, or fitting opportunity for dealing a blow at the enemy.

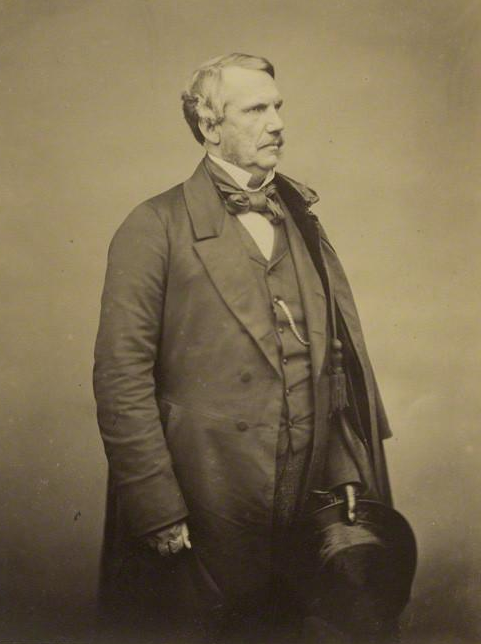

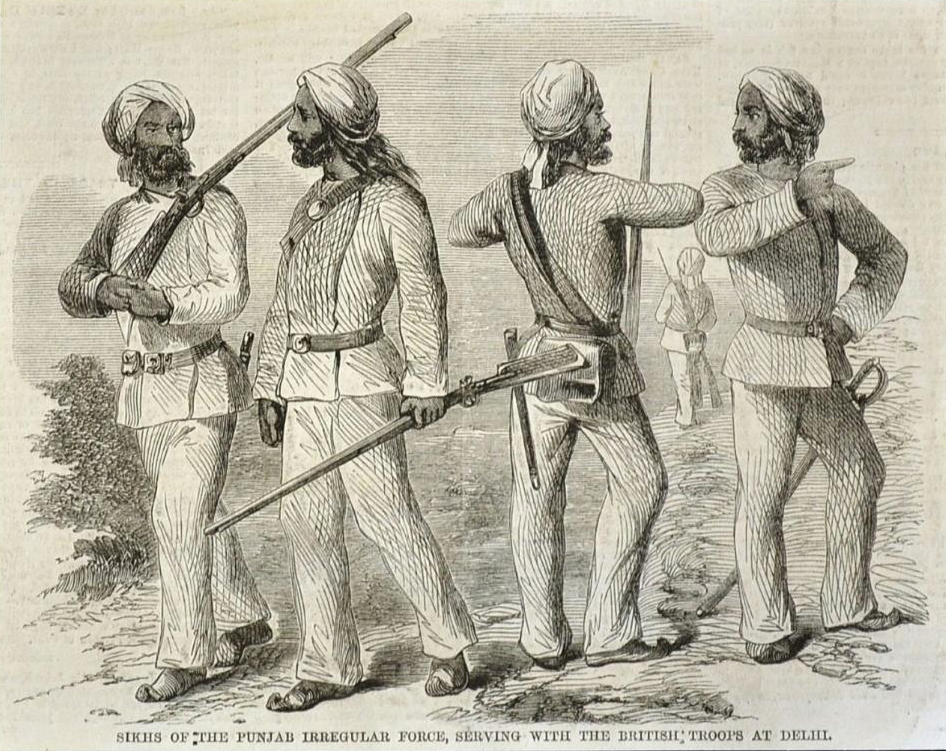

It was while they were thus stubbornly holding their ground that aid was being actively prepared in a quarter from which they could hardly have expected it. Governing the Punjab–the great province which it will be remembered had been annexed in 1849—was a man of commanding genius, Sir John Lawrence; and from the time that the news was flashed to him that Delhi had been captured, he had not only realised the full gravity of the situation, but had felt himself called upon to work with all his might to help in recovering the city. How Sir John was enabled to carry out his purpose—how he caused the Sikhs (or Punjabees), formerly the danger of India, to be the means of saving it, we shall more clearly understand by briefly glancing at his previous career.

The son of an officer, who had himself fought in the wars against Tippoo Sahib, John Lawrence— whose own wish to become a soldier like his three elder brothers had been overruled—at the age of eighteen entered the Company’s service as a “writer” (in 1829). His early years in India were spent in magisterial and revenue duties in the North-West Provinces, where he laid the foundation of that deep insight into the character and condition of the native peoples which was to stand him in such good stead in later years. Working on steadily in different parts of the Empire, he rapidly gained both the praise of superiors, and the admiration of subordinates; and it was at the close of the first Sikh war in 1846 that, as a reward for the masterly manner in which he had sent up supplies from Delhi, which enabled Sir Hugh Gough to win the decisive battle of Sobraon, that he was selected by the Governor General as the Commissioner for the newly-acquired Sikh district of Jullundur. So well did he then discharge his duties—introducing reforms of every kind, including a new system of justice, and constructing roads, bridges, and other public works— that ere long the conquered tribes were reduced to content, while the name of “ ‘Jan Larans Sahib’ became a household word among the people whom he had been so opportunely sent to govern.”

Then came a change. The second Sikh war broke out, and at first there was doubt lest the work he had begun would be destroyed; but in the end, when the whole of the Punjab was annexed, enlarged scope was afforded to his abilities. The province was now to be ruled by a Board of Administration, of which he and his brother, Sir Henry (who was to be the President of it), were two of the three members. Within a little over three years, mainly through the energies of the two brothers, the condition of the Punjab was entirely changed; and in place of chaos, order reigned through out the province. In 1852 the brothers disagreed on certain points of policy; and it was then, on both resigning, that the Board was dissolved; and the Governor-General, having determined that hence forth there should be one Chief Commissioner of the Punjab instead of three joint administrators, appointed John Lawrence to the post. From this time John Lawrence devoted himself with greater ardour than ever to organising the newly-acquired territory, and under his sway, says Captain Trotter, “the Punjab became, in truth, a model province. Crimes of violence grew rarer and rarer. The native officials in each district proved most useful and trustworthy helpmates to their English chiefs. The trade of the country flourished more and more…. The public at large were prosperous and contented.” In other words, by the year in which the mutiny broke out, Sir John Lawrence—who had been made a Knight Commander of the Bath in 1856—had, by his personal influence and ascendency, aided, be it said, by the able civil and military officers, by whom he had surrounded himself,[2] so gained the respect and affections of the Sikh chiefs and people, that these very men, who only a few years previously had fought the British so desperately, were now their faithful friends.

And what did Sir John Lawrence do when the news of the outbreak reached the Punjab? At the time when the telegram arrived he was at some distance from Lahore, the capital, recruiting his health; and the first measures necessary to be taken, namely, those which provided for the security of the Punjab itself, were carried out by the officer whom he had left at the head of affairs, Mr. (afterwards Sir) Robert Montgomery. In the province there were no fewer than 36,000 Sepoys “all ripe for revolt,” while the number of European troops was only about 11,000, and of Irregular Sikhs, 14,000; and in Lahore itself “there were three regiments of native infantry and one of cavalry waiting only for a post to bring them information of the hostile movements at Meerut to follow the example.” So there was no time to be lost if the atrocities at Meerut and Delhi were not to be imitated. As a first step, it was resolved to immediately disband the native regiments in the capital. Accordingly, on the next morning a general parade was ordered; all the Sepoys there, 3,000 in number, were drawn up as usual; and then, quietly surrounded by 600 British troops, whose twelve cannon were suddenly fixed in a commanding position, they were ordered to lay down their arms. Nor dared they refuse, seeing that the artillery and infantry were ready to open fire. And thus Lahore was saved. Then followed the disarming of other regiments in the Punjab, though all were not so successfully dealt with as those just referred to; and his own province being, by these prompt measures, rendered secure for the time, Sir John Lawrence was enabled to turn his attention to the pressing needs of Delhi.

Relying on their loyalty—the loyalty which, as we have seen, was solely the result of his strong, just, and merciful government—he now boldly called upon the Sikh chiefs for aid; and not only did they respond to the call with alacrity, but ere long, in addition to the 14,000 Punjabees already bearing arms, who remained staunch, a force of many thousand others was raised. Then as fast as these could be organised and drilled they were despatched to Delhi, a few being also sent to other places.

As illustrating Sir John’s method of procedure, as well as the foresight he showed in thus seeking help from the Sikhs, it is related that on one occasion “he sent for a former Sikh aide-de-camp of his own, and with him made out lists of the leading chiefs who had suffered from the rebellion of 1848. Then he wrote to each urging them to show their loyalty by coming to him with a picked force of retainers. The chieftains came in with their followers, and were promptly despatched to Delhi. The measure had a double effect. The beleaguering force was most sensibly strengthened; while the Punjab was denuded of so many rallying points for disaffection. Envoys from the mutineers came to tamper with these very men, only to find they had left their territories to serve under the English.

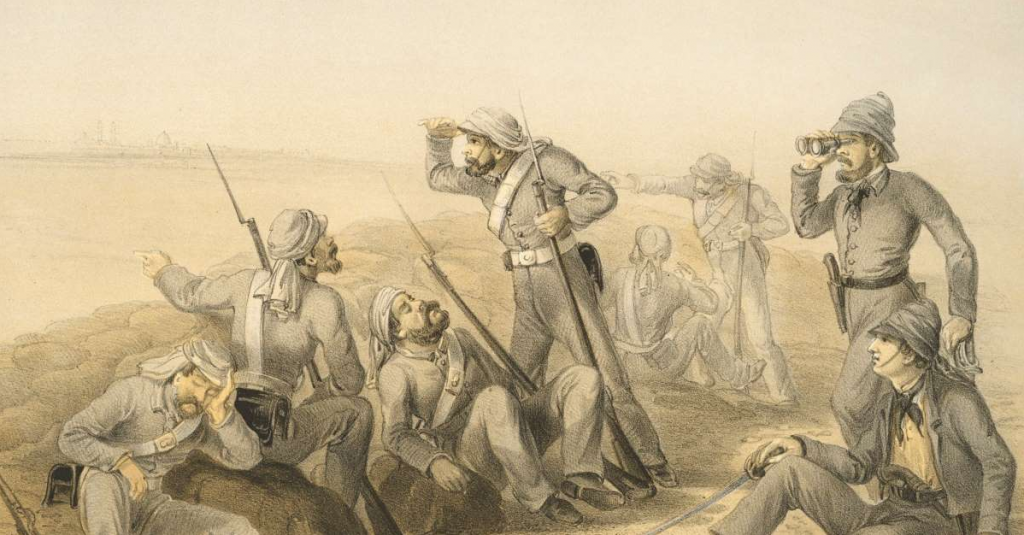

Thus some weeks passed by; and now nearer and nearer came the day when Sir John Lawrence’s exertions were to bear fruit. On the Ridge outside Delhi, the British had been gallantly holding their own, in spite of being furiously assailed both by the guns of the city and by attacks made by the enemy in their sorties; and though, thus far, the capture of Delhi had not been accomplished, yet by the continued relays of men, horses, guns, and other necessaries, which Sir John had sent to the camp, their position had been most effectually strengthened.

And now arrived from the Punjab the “grandest contribution” of all. Among the distinguished officers by whom Sir John Lawrence was served was Brigadier Nicholson; and at the time when the disbanding of the Sepoy regiments had been carried out in the Punjab, he had been put in command of a Movable Column, 2,000 strong, which had been organised so as to be always available for immediate service, if required. When, towards the end of July, he found that Delhi was still in the hands of the mutineers, and that each week was adding to the numbers of his garrison, owing to the fresh bands who poured in from various quarters, Sir John, feeling that the Column could be dispensed with in the Punjab, determined that Nicholson should march down to Delhi with it, and then and there urge the general in command not to wait any longer, but to attack the city at once.

This course was taken, and we are told that when, on the 8th of August, the Brigadier, who rode into the camp a week ahead of his men, to consult with the General, appeared, “the mere sight of his tall, stately figure and sternly handsome face gave new heart to the war-worn defenders of the Ridge; and the subsequent arrival of his column, headed by the noble leader himself, was hailed by all men as a sure precursor of the victory yet to come.”

At length, after the arrival of the great siege-train, and the last detachment of men, from the Punjab, the assault on Delhi, before which the British force had held their position for three and a half months, was begun.

It was on the 13th of September, after an incessant stream of shot and shell had been poured into the city for nearly a week, that a breach in the formidable walls was reported; and then came a most deadly struggle.

Early on the morning of the 14th, the storming columns—the leading one of which was headed by the gallant Nicholson, who, alas! was one of the first to fall—dashed through the breaches; and then, the famous Cashmere Gate having been blown up—a feat performed by a noble band of sixteen Engineers, of whom, save four, all perished in accomplishing the task, the city was entered by the whole force. For six days after this the fighting was carried on in the streets, during which both the besiegers and the rebels fought with terrible fury; nor was quarter given on either side.

It was on the 20th that the city was captured, though after a loss in killed and wounded of no fewer than 3,537; and by this brilliant triumph, which, be it remembered, was achieved before the arrival of reinforcements from other parts of the Empire or from home, the rebellion received a blow from which it never recovered. “With the fall of Delhi,” says Mr. Bosworth Smith, the biographer of Lord Lawrence, “fell the hopes of the mutineers. The extremity of the peril was over, for the rebellion was crushed at its centre, at its heart. The fortifications which we had ourselves erected or repaired, the arms and ammunition which we had ourselves collected, the historic prestige and the inherent strength of the resuscitated capital of the Moguls, had all failed to withstand our onslaught; and how could any other city, or any other force, hope to be more successful? The struggle, indeed, was to be protracted, for many a long month to come, in the North-west and in the Central Provinces; but on the part of the mutineers it was no longer a struggle for empire, but for bare life. Instead of boldly taking the offensive—with the one exception of the force at Lucknow—they appeared before us only to vanish away; and our chief difficulty henceforward was to hunt them down, not to beat them when we had found them.”

And now followed a memorable episode. On the day after the capture of the city, Captain Hodson, the daring leader of some irregular cavalry known as Hodson’s Horse, whose exploits brought him into much prominence during the siege, went forth with fifty troopers to arrest Bahadur Shah, who, as we have seen, had been proclaimed Sovereign of India. He had escaped to the tomb of Humayoon, a huge building a few miles from the city; and it was from this place that, after two hours’ bargaining for his own life and that of his queen and favourite son, he was dragged out, and, having been taken back in a bullock-cart, handed over to the authorities. On the next morning Hodson captured two of Bahadur Shah’s sons; and it was while they were on their way to Delhi that—fearing, as he afterwards said, lest a rescue would be attempted by the crowd—he shot them dead with his own hand.

In the following January, in the palace of his own capital city, Bahadur Shah was tried as a traitor to the State for proclaiming himself Sovereign of India, for encouraging and aiding the mutineers, and for the murder of forty-nine British officers, women, and children, at Delhi. He was found guilty, but his life was spared; and it was with the sentence of banishment for life to Rangoon, in Burmah, which was soon after passed upon this its last representative, that the dynasty of the Great Moguls was finally extinguished.

To one man—to John Lawrence”[3]—belongs the undying glory of having been mainly instrumental in causing the splendid victory at Delhi to be achieved. But for his unwearying exertions in pouring in aid from the Punjab, it seems probable that not only would the mutineers, gathering new courage day by day, have overwhelmed the little force on the Ridge, not only would the rebellion have spread more and more, but that even the Empire itself would have been lost.

Truly the name of “The Saviour of India” was not unearned by him!

______________________________________

Footnotes

[1] According to their religious laws, the Hindoos are divided into castes or classes. By breaking such laws they lose caste; and, thus forfeiting the privileges of their respective orders, they become pariahs, or persons of no caste.

[2] As showing the high regard in which those who worked under him held their chief, the following extract from a letter, written by an old comrade of Sir John Lawrence, is of interest: “He had nothing mean in his nature; no spite or malice…. He was the biggest man I have ever known. We used to call him ‘King John’ on the frontier, and it is as such that I still love to think of him.”

[3] For his services Sir John Lawrence received the Grand Cross of the Bath in 1857, followed, in 1859, by a baronetcy and a pension of £2,000 a year; and when, in 1864, Lord Elgin died, he was appointed to succeed him as Viceroy and Governor-General of India. On his return to England in 1869—ten years before his death—he was created a peer with the title of Baron Lawrence of the Punjab and Grately.