Editor’s note: The following is extracted from General George S. Patton, Jr.: Man Under Mars, by war correspondent James Wellard (published 1946).

Earlier posts in this series:

The Gethsemane of the Hedgerows, Part 1

The Gethsemane of the Hedgerows, Part 2

Suddenly the war became fun. It became exciting, carnivalesque, tremendous. It became victorious and even safe. We awoke on the morning of Sunday, the 30th of July, with the feeling that the war was won — in spirit, if not in fact.

Patton and the Third Army were away.

Those were indeed tremendous and even delirious days. You would walk into Corps Headquarters to find the G2s (Intelligence Officers) wiping out entire dispositions on their celluloid-covered war maps. All the little red squares and circles representing German positions on the Cotentin peninsula and all the little blue ones representing Allied dis positions were being rubbed off with big sponges, and bald- headed sergeants, with pockets full of draftsmen’s pencils were re-disposing the entire war fronts.

At the 8th Corps, which held the western sector of the Normandy front, the G2 colonel said: “We’ve lost contact with the enemy.”

Patton gave us his last press conference in his apple orchard headquarters. He was the same as ever, resplendent in khaki and medals, with his smooth womanish face, small mouth, colorless eyes, and quiet manner. This day, however, his white bull terrier, Willy Patton, Jr., tended to steal the limelight from his master. During the conference, the white eyed hound stood in front of the respectful war correspondents, chose a lap, and climbed on.

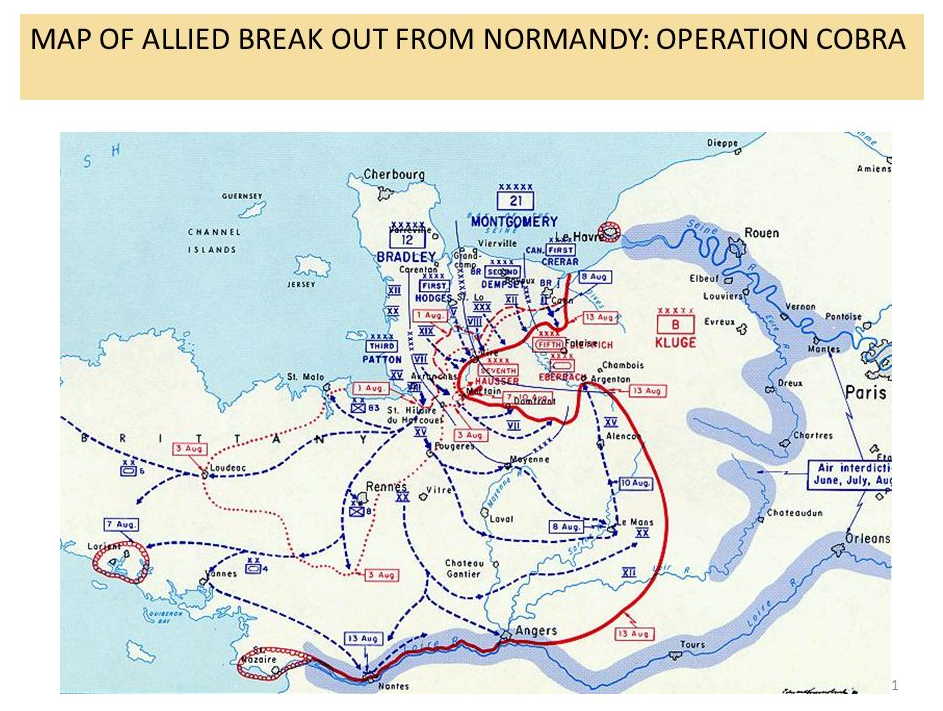

Patton announced that he was ready to go. The 4th Armored Division was already moving down the Lessay-Coutances road.

My jeep party, consisting of Norman Clark of the London News Chronicle and Cornelius Ryan of the London Daily Telegraph, decided to move on with it. We packed our belongings in the trailer attached to our jeep, and said good-by to the press camp in the apple orchard for the last time. We had no destination, because the war was suddenly moving so fast, nobody could say exactly where our advanced units were. Everything in the Third Army was now roaring south through the Lessay gap, and down the coast highway through Coutances and Avranches. Avranches marked the shoulder of the Brittany peninsula, and it was the gateway to the interior of all of France.

We could see, as we rode along in the clear, white sun light of that morning, July 30, that the “Gethsemane of the Hedgerows” was over. No more banked hedges, ditches, and flanking poplars. South of Lessay the country rolled and heaved in a sweeping landscape. The roads were wide and fast to travel over. Down these roads, on this July morning, was rolling the 4th Armored Division, as though there was nothing now to stop it between the Normandy beaches and the German frontier. This was the feeling we had that morning, and the feeling proved to be almost the fact of the matter.

The 4th Armored, now in action for the first time, was largely responsible for this impression of urgency. It had been trained with the power and speed of a panther. It took to tank warfare as a trained swimmer to a pool of blue water. Its tank crews and armored infantrymen were uncannily fearless and skilful. It began its battle career in this way, and eventually raced across France and across Germany and into Czechoslovakia as cleanly and swiftly as a bullet. It was an altogether incredible battle unit, and Patton invariably used it to spearhead all his major drives.

It was the 4th Armored we followed that morning; and we found, as we were always to find whenever this division “took off,” that our rear echelons had lost contact with them. The lead tanks had “just gone.” Gradually, as we went south of Coutances, we found the countryside becoming emptier of troops and we had that disagreeable feeling of being between our own advanced elements and our own rear. In this war, No Man’s Land lay not between our forward units and the enemy, but behind our most advanced tanks. In this zone, pockets of the enemy had been by-passed. The infantry came along later and cleaned them out of woods, trenches, and houses. Along the lonely stretches of road friendly vehicles raced as fast as they could, anxiously scanning the fields and woods on either side.

This was how we were riding, when we came across a little group of jeeps at a crossroads south of Coutances called Trelly. One of the jeeps bore the two-star insignia of a major-general. This was General Wood, commander of the 4th Armored. He was a hard-faced, leather-booted cavalryman, and was concerned at the moment with keeping his tanks rolling. I asked him where he wanted them to go. He said, “It doesn’t matter, so long as they keep rolling.” He did not yet know whether, once through the Avranches bottleneck, he would swing west and cut across the Brittany peninsula or whether he would turn east be hind the German Seventh Army. I said, “What happens, General, if the Germans cut you off by driving through to the coast behind you?” The General said:

“Let ’em. That’s what we want ’em to do.”

This, then, was now the spirit of the war. This was not the mechanics, the ballistics of invasion. It was not aerial or artillery bombardments, saturation bombing, frontal assaults, hedgerow war, war of attrition. It was not the Bradley or Montgomery strategy. It was pure Patton. A whole armored division was being hurled through a narrow bottle neck, and ordered to keep rolling as far and as fast as it could. It was brilliant, dangerous, and unpredictable. It was the piratical technique applied to modern war.

What had already happened to the 4th Armored was what had to happen. Some of their lead tanks had been ambushed and knocked out. Others had gone so far ahead, they had lost contact with the main force. Others were behind the Germans, without either side knowing how or where. Tanks had begun that cutting and slicing technique which was Patton’s favorite and most brilliant tactic. In the darkness and the confusion, they had bumped head-on into powerful German units, and battles of annihilation had been fought all night.

General Wood himself directed us to a place down a side road from the Trelly crossroads where the Third Army’s first big battle had been fought. “Go take a look at that road,” he said. “You’ll see something unusual.” Then he climbed aboard his jeep, and his little column roared away. I thought they were more like Indian fighters on little white horses than modern soldiers in jeeps.

The spectacle General Wood was referring to was one of the most awesome I had seen in four years of war. It was a column of seventy German vehicles which had been ambushed by a single American medium tank, and the whole seventy, tanks, field guns, half-tracks, ambulances, trucks, private cars, the General’s caravan — in fact, the entire headquarters column of an SS Panzer division — had been methodically knocked out.

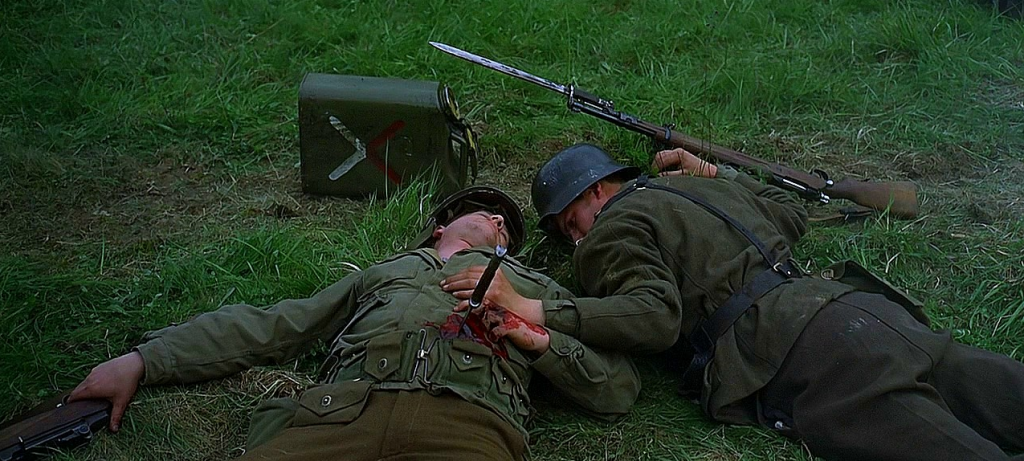

We wandered down the country road along which this dead column lay black between high hedges. Its head was a Mark IV tank, knocked out with the second shot from the American Sherman which lay, also dead, under a tree, a hundred yards further down the road. Next came an enormous mobile cannon. Then came half-tracks, more tanks, three captured American tanks, trucks, private cars, the German General’s caravan. All over these vehicles, on the road, in the ditches, in the fields, lay the SS men. Their corpses were truncated, bisected, mangled, and sometimes unmarked, so that I saw many of them sitting at the wheels of private cars, as though still in the act of driving. In the backs of other cars sat wounded men, with their arms in slings, sitting upright and relaxed, like sleepers.

Some sad-eyed G.I.s were wandering along the road, and they took us to see the officer who had fought this battle. He was a big, quiet captain, and his eyes were bloodshot with fatigue, and he was not elated or impressed by his victory. His name was W. C. Johnson, and he was once a football coach at Lafayette University, Indiana. The captain had commanded the regiment of the armored infantrymen out of the 4th Armored which had completed the ambush of this SS column, and had fought the SS men all through the night. The SS had fought to the last man. They could not go forward, because the Sherman had knocked out their lead tank. They could not turn round, because the road was too narrow. They could not go over the fields because the hedges were too high. They could not go back because the Americans had closed the Trelly crossroads.

Captain Johnson, with his infantrymen, had arrived on the scene at eleven o’clock the previous night. The battle had ended at six o’clock that morning. Hundreds of SS men had died, and scores of Americans had died, too. The adjacent field was full of dead men. Some of them, American and German, lay head to head, because towards morning, said Johnson, the fighting had become hand-to-hand.

The SS headquarters men had brought all their loot with them. Fur coats, women’s silk underwear, musical instruments, giant cheeses, boxes of cigars, bottles of wine, mounds of wool, shoes, shirts, hats, uniforms, lay scattered all over the road. There was enough loot in that column to have stocked a department store.

I believe this was the first time in this war any Allied unit ambushed a German column of this size and importance. It was also the first time Allied armies had broken through and got behind the Germans. What we were now seeing was quite different from what we saw in Africa, Sicily, and Italy. What we were seeing was the beginning of a German rout, which became within the next few weeks the biggest rout of armies in the history of the world.

The signs were all around us. German vehicles and equipment lay littered over the countryside. Their tanks were smoldering beside the roads. Their guns stood abandoned in the fields. In the ditches rested the Nazi dead in gray-blue field uniforms. It became evident, as we went further in the wake of the 4th Armored Division, that a major disaster was beginning to overtake the Reichswehr.

[…] (Continued from Part 1) […]

[…] (Men of the West): Suddenly the war became fun. It became exciting, carnivalesque, tremendous. It became victorious […]

[…] (Men of the West): Suddenly the war became fun. It became exciting, carnivalesque, tremendous. It became victorious […]