Editor’s note: The following is extracted from General George S. Patton, Jr.: Man Under Mars, by war correspondent James Wellard (published 1946).

One could see immediately on landing how crowded was the Norman countryside with the tremendous forces the Allies had already put onto the continent. The stretches of landing beaches were packed with vehicles, which rolled in sand and dust clouds onto the roads, and were parked in hundreds of fields. The feeling was that we were really winning. You could travel without fear of German planes or long-range guns. It was very different from North Africa, Sicily, and Italy.

Patton established his headquarters in a country of apple orchards around the Norman villages of Nehou and Saint Sauveur le Vicomte. The headquarters spread over a wide area, and part of it was the G6, or Psychological and Press Department. Here thirty correspondents had their own camp in their own apple orchard and there foregathered some old hands at war reporting and some on their first big assignment: Ernest Hemingway, Ira Wolfert, Jack Belden, Joe Driscoll of the New York Herald Tribune, Tom Treanor, who died in France, Tom Wolfe, Duke Shoop (or Dook the Shoop as we called him), Richard Stokes, and Norman Clark, and John Prince of the English Press were among those present. We set up house in three large tents, under the “command” of a lieutenant-colonel, who was not, most of us felt, either a sympathetic or efficient public relations officer. But public relations officers were a curious offshoot of this war, and their job of controlling large groups of war correspondents who were civilians and individualists, antipathetic to regimentation in conduct or dress, was not an easy one. I met very few public relations officers who were universally liked and respected, and I consider the American army handled this branch of the war clumsily and ineffectually. The British, with more experience and wisdom, handled it extremely well.

General Patton, acutely conscious, since Sicily, of the power of the press, soon visited this unmilitary establishment which was set down in the midst of his professionally military headquarters. He came into our apple orchard the day after we settled in, and was greeted by the permeating stink of many boxes of Camembert cheese which provident journalists had stored away under their camp beds. He was also greeted by men in helmets, men without helmets or any headgear at all, and some in caps of varying hues and shapes. His orders were for all military personnel to wear their helmets on pain of court-martial, but many of us managed to follow the Third Army from Normandy to Czechoslovakia in service caps. The military policemen used to stop us in the beginning, but hearing we were correspondents, they assumed we were beyond disciplining, which was roughly the case.

Patton shamed us in his appearance. He was resplendent. His helmet was lacquered and shone with paint and three stars. His tunic, cut on the cadet model, carried three rows of ribbons on his left breast. His beloved pistols were strapped at his waist, and he carried a riding crop. He was upright, soldierly, and amiable, and gave me — as he man aged to give most civilians — the impression that I was an intruder in a warlike world.

To me, Patton’s appearance and manner were always astonishing. There is nothing of the swashbuckler about him on the surface. He is a quiet man, even with well-con trolled signs of nervousness. His voice is high and thin. He speaks for long periods without manifesting in outbursts the extreme emotionalism of his nature. He can, if he wishes, speak without profanity, which he does not use as most soldiers use it to distinguish them from civilians. His use of language is, in fact, rather Elizabethan. It is lusty, and he likes words. I noted that he pronounced French names correctly, which only one out of ten thousand American soldiers did. I noted, too, that he is a man who by his fine stature and strong personality elicits sycophancy from other men. Our group around Patton that afternoon under the apple trees flattered and indulged him, partly from awe, partly from a desire to exploit him.

The approach was successful, and Patton did give us a detailed account of his forthcoming battle plans. He said we would first make a hole in the German lines, probably in the western or Lessay sector, and through this hole he would hurl his armor, fanning it out in two great spear heads, one of which was to go west to Brest and cut off the Brittany peninsula; the other to go east and encircle the German Seventh Army. He said he would be ready to go within two weeks.

He had bet the war would be won by November 11.

While waiting for Patton to make his break-through, we wandered about the front, through Bradley’s First Army and Montgomery’s Second Army sectors. I was able to orient myself again to the martial life, renewing my acquaintance with divisions I had known in the Mediterranean, and above all, readjusting my senses to the sights and sounds of war.

I could see from my wanderings along the front that the Germans were much weaker here in France than they had been in Italy. We never saw a Nazi plane, and we were seldom shelled by Nazi guns. The absence of German air force and artillery was significant. It enabled us to dispose our forces without interference. It prevented the Germans from anticipating our moves, and though their agents reported the whereabouts of Patton, they could not discover the size or mission of his army. The fact was, Patton actually had no army at this time. The army was formed at the last minute from newly arrived divisions and from First Army units, which were transferred from Bradley’s to Patton’s command.

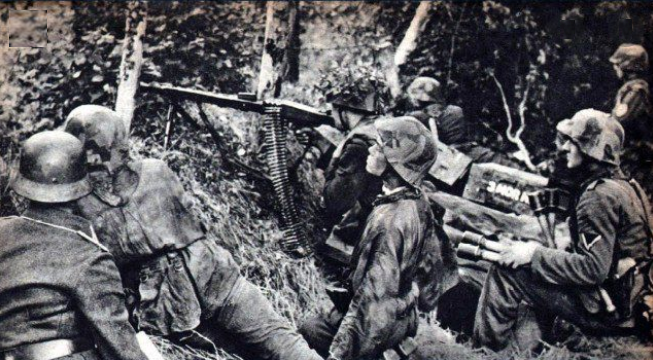

The Germans, though greatly outnumbered and outweighed, were fighting with extraordinary skill and cunning. We had a decisive superiority in men and armaments, but they had the advantages of terrain, camouflage, and subterfuge. We were fighting then in the hedgerow country. Normandy is divided into thousands of little fields, separated by high-banked hedges and flanked by trees. The Germans dug into the rear of these banked hedges which formed natural tank barriers. Our infantry had to pry them out, hedge by hedge. Our losses were heavy. All over the countryside they had built woodland fortresses such as the Japanese used in the jungles of Asia. Camouflaged ladders led up to tree platforms from which snipers could fire, using flashless powder. I examined some of these places. They were made with characteristic Teutonic skill, and the ladders, made out of the same wood as the trees they leaned against, were beautiful examples of German carpentry.

This art of camouflage, which the Germans developed to perfection and which the Americans seemed to make no attempts to develop at all, almost counteracted our tremendous air superiority. Our fighters and bombers were after the German convoys all day, and seldom could find any. Yet the enemy was constantly moving supplies to the front. For a long time our intelligence was puzzled by the complete absence of enemy vehicles on the roads. The answer was that the Germans were cutting long sections out of the hedgerows, and filling them in with their convoy trains, which were netted and painted to resemble the original hedges. The convoy drivers stayed in their vehicles until night, when the train side-slipped onto the road and rolled frontwards again.

Bradley and Montgomery kept battering away frontally at the German lines, and our progress was so slow it looked as though we would be months breaking out of a country which the infantryman now called the “Gethsemane of the Hedgerows.” Our strategy at this time started to resemble the strategy of the last war. We were using weight in a straightforward, pounding way. Mass bombing was tried again and again. On July 24, the major part of the Allied air forces was supposed to blast a hole through the German lines in the St. Lo sector. During the morning we watched a long procession of medium and heavy bombers flying east, but learned at the 19th Corps of the First Army that the attack had had to be postponed on account of the overcast.

The next day the air attack did go in, with 2,215 Fortresses, Liberators, Marauders, and other airplanes, dropping an estimated 4,000 tons of bombs along a narrow sector of the front facing the 7th Corps. Two hundred tons of these bombs, or five per cent of the total, fell on our own forward troops, killing and wounding many of them, including a general, Major-General L. S. McNair, Chief of Air Corps Ground Forces.

Everybody, Americans as well as Germans, was shaken by this earth-rending bombardment. I talked to Germans who survived it, and were taken prisoner in the subsequent American infantry attack. They said the 4,000 tons of bombs had stunned them, but had not killed many, as they knew it was coming. They had watched the abortive air armada the day before, and divined we would try it again as soon as the weather favored. So they had dug their holes in the ground, and survived the storm; but the American infantry was on them before they had time to get out of their holes and reform.

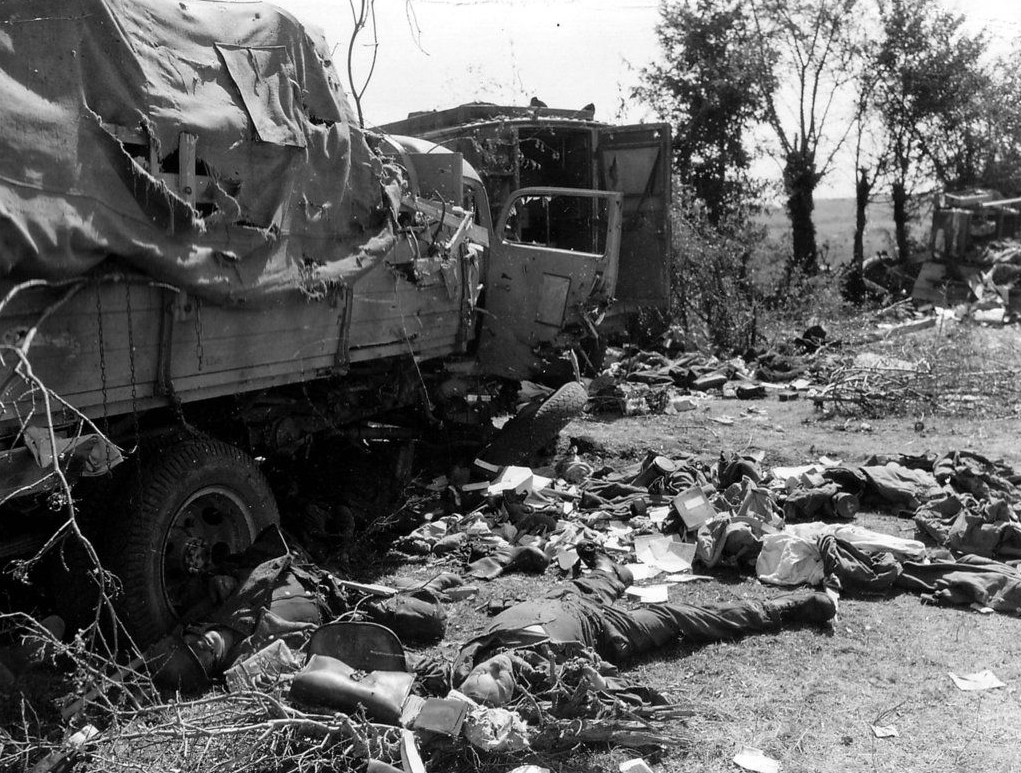

By July 26, Bradley had broken the German’s Normandy line. Using the 1st, 5th, and 9th Infantry divisions, veterans of Africa and Sicily, he was shoving the whole German Seventh Army back. The signs of a break-through were now increasing. Our tanks had begun to break loose. We began to see the litter of wrecked or abandoned German equipment; burning tanks, swollen corpses, bloated cattle, lay all over the countryside, stinking in the hot sun. Bradley started by-passing German strong points, like Marigny, which was held for a few hours by fanatical Nazi rear guards. There was still no German rout, but they were breaking.

By July 28, Patton was ready to go. He had the hole in the German lines which he wanted. It was in the desired place, on the west side of the Normandy peninsula, with the sea on his right flank.

On the 28th, I went to the “hole” where Patton had said he would pass through. It was at the little town of Lessay, on the Ay River. The river had been a natural defensive position in the Germans’ east-west defense line across the Cotentin peninsula, which rises into the Atlantic in the shape of a cat’s head, with Cherbourg at the top. The Nazis had abandoned Lessay without a fight, when Bradley broke their line in the center and outflanked it. Now it was a ghost town. I remember walking in with a company of American combat engineers, each of us walking in the footsteps of the man ahead. We knew the town would be heavily mined and booby-trapped. On such occasions, every man is silent. He watches the ground, and the silent shoes of the man ahead. You wonder then in whose footsteps the first man is walking. Our entry into Lessay was silent and uneventful, though we were expecting snipers. The combat engineers who were these first men in, have to expect something of everything in their job. They may have to lift mines under artillery fire, repair bridges under machine gun fire, or tape out safe roads while being sniped at. But all we met in Lessay was death and the stink of German corpses. The town had been hammered into piles of rubble by our artillery. It was empty, and no faces showed behind the fluttering shreds of curtains. No one was sitting in the local cinema, which had the roof blown off, though the rows of wooden seats remained. The place was typified in a fully clad German infantryman lying on his back by the roadside. He was very dead. His face had swollen and blackened until it resembled a gas mask. And from his pack, which contained the “souvenirs” so beloved by Americans, ran a fine wire. The German corpse, like everything else in Lessay, was booby-trapped.