Editor’s note: The following is extracted from One-Man Air Force, by Captain Don S. Gentile as told to Ira Wolfert (published 1944).

Looking back now from my vantage point after some hundreds of scraps with the Germans — of bouncing them and of being bounced and of the bangs and prangs and clobberings and of being clobbered — I would say now that in those ancient days of 1942 and 1943 the confidence I had in my ability to kill the Nazis and to keep them from killing our men was misplaced.

I know now how much remained for me to learn before I could handle myself in the rough, fast, big-time company they have operating over Europe. But in those days I didn’t even know how little I knew.

After I had a few fights under my belt and made a few scores I became again what I had been before the war — a kid full of beans, who, when he sits in an airplane, feels there is nothing in the world that can master him. Fortunately for me, our side of the war was up against a situation in those years that prevented me from acting on my belief in myself. Otherwise, I probably would have had my beans cooked in some gasoline fire long before I learned how much there is to know besides flying about this business of fighting.

We were on the defensive then. When we first started going on the offensive with Flying Fortresses and Liberators our fighter planes remained on the defensive, their job being to provide a close escort for the heavy artillery and not to mix it with the Germans but just to break off their attacks.

During most of this period Captain Carl (Spike) Miley, a Toledo, Ohio, boy whose savvy I have only now begun to appreciate, was my flight leader and he kept a tight check on me to hold me in the formation. I wanted to make the touchdowns. He wanted to keep the team together, running the interference for the touchdown-scoring bombers. We didn’t quarrel, but I became restless under his control. And the more restless I got, the firmer did Spike pull the reins. When he finished his tour of operations last September and was ordered home, Spike recommended me for his place as flight commander. After I got the promotion he took me aside.

“All right,” he said to me, “you’re red hot and it’s natural you should want to be a firecracker over here. But you’ve got boys following you now who have things to learn before they get red hot. They’re going to follow you wherever you take them. Remember that when you take them anywhere. It’s not only your brains that are going to get knocked out, but the brains of the kids who are depending on you.”

That gave me a new slant, and I kept the boys under as tight a rein as Spike had kept me. But the whole thing did not fall into place for me until January 14 of this year when I bounced myself into the bag and I had to use every single thing I had ever learned in combat to get out with the Germans dead and myself alive.

There is a little song Lieut. Jack Raphael of Tacoma, Wash., worked up to commemorate the occasion. It goes to the tune of “Tramp, Tramp, Tramp, the Boys Are Marching.” Here are the words:

“Help, help, help! I’m being clobbered

Down here by the railroad track.

Two 190’s chase me around

And we’re damn near to the ground,

Tell them I got two if I don’t make it back.”

The song is good, but the way the story really went was like this:

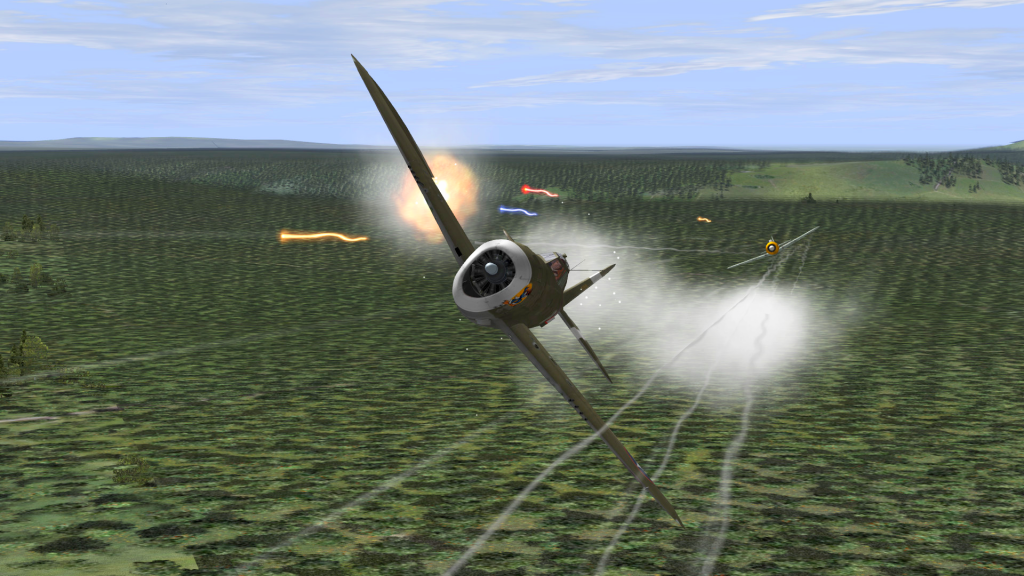

We were on a sweep in the Paris area, and down there somewhere I saw and reported a group of some fifteen or twenty Focke-Wulf 190’s flying east about 5,000 feet below us. We bounced them, and I picked out two stragglers. I yelled to my number two man and he said: “Keep going; I’m with you!”

The Huns turned into me, and we closed the distance between us at better than 700 miles an hour. At the rate of 700 miles an hour you can eat up all the distance there is in one gulp, but while you’re doing it it seems slow. You can think of a thousand things, and nothing seems to be happening in your life except that the plane is coming slowly toward you and you’re living a lifetime — as if it was a speed-up movie reel — and aging fast and growing old and older and looking suddenly at the end of your life in just about the time it takes to say it.

This moment of closing in on a head-on attack can sometimes decide a whole battle. The question is: “Who will break off the attack first?” The one who turns away first goes on the defensive, and the fellow with the guts to stick it out swings on his tail and has a chance to make the kill.

So I just sat still in the cockpit, with my thumb on the gun teat, cozying it and stroking it, waiting and growing old and older and looking suddenly at the end of my life. Then the Huns broke — and I knew they were mine. They broke together to keep their formation, and I knew they were afraid of me and that I was going to kill them.

The Huns drove straight for the deck. A Focke-Wulf 190 is better on the deck than the kind of Thunderbolt I was flying then. I thought I could make up the advantage their machines gave them by this feeling I had in myself and by the fact that I was sure I had instilled in them that I was their master and was going to kill them.

I had had some experience in instilling this feeling into the Germans. Only a few days before the mere act of diving down to the deck with a Focke-Wulf, and of showing myself confident enough to be thrown to him as if I were a bone being tossed to a dog, had so panicked him, despite his mechanical advantage in a fight, that he had straightened out in a run from which he hadn’t a prayer of a chance of emerging alive.

I was so intent on getting those Huns that I couldn’t think of words to say into my radio to make sure my wing man was still with me. I wanted to make sure, but I couldn’t take my eyes off those Huns for a second or I’d lose them, and besides I just couldn’t think of any words to say into that radio. They wouldn’t come out of my head and they wouldn’t come into my mouth.

What happened to my wing man was that on the way down to the deck we were bounced by some other Jerries and he turned off into them to break up their attack. By the time he had done that we were as good as a million miles away from him — those two Huns, who were racing along the edge of their graves and myself, who was trying to push them in.

We were lost to the sight of anything in the air against the black, hunkered-up green of the forest of Compiègne. I didn’t realize I was without any wing man to protect my tail until after I had got both Huns. One of them crashed in the open country at the edge of the woods and the second one went splintering into the middle of all those trees there.

Compiègne was where Hitler forced his armistice on the French, and it seemed to me a rather nice gesture to throw the bodies of two of his fliers down his throat there.

But in the meantime I was without any wing man. I found this out when, just after I pulled up away from the trees, tracers started shooting past me and I saw two more Focke-Wulfs on my tail, with nothing between me and them except the very thin, very naked air.

When you’re down on the deck trading punches with a Focke-Wulf and spotting him that mechanical advantage, you have to have something to help you, even if it is only the feeling of fear in the enemy’s mind. But these two new boys were not afraid of me. Oh, no! They came barreling right in, red hot for the kill. They hadn’t even seen me shoot down those other two guys and quite likely they thought I was just some rabbit who had come down to the deck to get out of a fight going on upstairs. Psychology wasn’t going to help me with them.

So these two Focke-Wulf 190’s came barreling in on me, red hot and sure of themselves and of a kill — so sure that they held their fire until they were right on top of me. The lead Hun was close enough to me when he started to fire for me to hear the ripped-out chugging of his machine guns and the soft poom-poom-poom of his cannon.

There was this sound, and at the same time tracers were going by me and my plane was starting to splinter around me. As I turned my head in a “what in the name of damnation is going on here” attitude, I saw a 20-millimeter shell go into my wing and saw the metal of the wing flower and open like a torn mouth and saw my tail quaking and shuddering with animal movements under the blows of more cannon shells. And I stared right into the millstream of bullets behind which sat the number one Hun looking like a doll there — looking inanimate and stolid and mechanical with his mask on.

I held my eyes into this millstream of bullets for what seemed a long time to me. I guess my eyes must have been pretty wide open, too. Then I threw my plane around and right into him, thinking, if I ram him I’ll take the bastard with me and if I don’t try it will be me going alone.

He had to pull up and over me. I stayed in a port turn because the Hun’s wing man, number two, was still coming in. This number two guy ran out of guts and broke away. Right quick I threw my Thunderbolt into a starboard swing and let loose a burst at the guy, but didn’t hit him. My nerves at the time were not conducive to accurate gunnery. I was starting to close on him and to give him another burst when I found out I had used up the last of my ammunition.

In the meantime the lead Hun who brushed over my head when I had swung in on him had pulled up and positioned himself for another attack. He made it while I still was in my starboard turn and just as I was discovering I had no more bullets left.

He had about a 30-degree deflection shot, but was giving it too much, and I could see his tracers hitting in front of my nose, maybe 30 or 40 feet in front. I kept watching his tracers walk toward me slowly as he corrected his aim, and it was one of the hardest things I had ever had to do. I had to keep along the line he was taking until the last minute. If I changed too soon he would anticipate it and I would lose my chance of surprising him off my tail. So I just kept still and watched the stream of tracers inch slowly, like a flooded river, lapping toward my cockpit and didn’t think of anything, but just told myself in just these words: “Don, hold on to yourself; keep yourself steady and you’ll get out of this all right. Don’t panic, Don!” Like that, over and over again.

When the tracers got up to the edge of my cockpit I threw the airplane to port as hard as I could, giving it the maximum on the rudder and stick that you can without going into a spin. The whole plane shook — I could feel it shaking. That poor, old torn out tail of mine was like a horse trembling, and I could feel the spine of the plane just bending. And I could feel that spine in my teeth, as if my gums were grinding under my teeth, but I held it there and held it and held it until I couldn’t any more.

I was on the edge of a spin when I pulled out, and the tracers were still coming at me. I don’t know who this Hun was, but he was a wise, old cookie all right — no kid at all, but a hard man who knew the tricks of the trade and knew he had a plane that could turn inside of mine and felt sure he was going to get me.

The best I could do with my turns was to keep him part-way off my tail and give him deflection shots at me, that is, keep my line of flight at an angle to his so that he would have to shoot ahead of me to try to hit me, which is the hardest kind of shooting to do.

I am not sure exactly how many times I sat still in the cockpit, just watching the tracers walk to ward me and telling myself, “Don, hold on to your brains!” But I think it was three or four times.

Then, suddenly, in a turn, my plane flicked over on its back, and I was right over the trees of the forest of Compiègne. The whole fight had been from 50 to 100 feet above the trees. Now the trees reached up for me, and I had my head stuck down toward them, but I didn’t panic. I just concentrated on remembering where that Hun was, and when I made my move to roll out of that flick I rolled in the direction where, if I came out at all, I would be alongside him and he would be off my tail at last.

It worked. I rolled out of my upside-down position, although I was that close to the trees that the whole air inside my cockpit seemed green with them. And when I came out right-side up again, there I was where I figured I would be — alongside the Hun and out of the angle of fire of his guns.

I found words for the radio transmitter then. “Help!” I screamed. “Help! I’m being clobbered!” I wasn’t fooling. I really screamed. I heard some of the boys call down: “Where are you?” to me, but I couldn’t take time to look and they never found me.

That Hun and I kept our eyes on each other. I had to wait for him to make an attack, and I think he suspected it. I think he knew I was out of “ammo” and that it was up to him to make the play.

A lot of things he did told me I wasn’t bluffing him — not that crafty old cookie, not him. But when he turned to attack I turned in on him and charged him head-on. That gave him hardly any time at all to shoot. The best shooting range lasts less than 300 yards all told, and airplanes closing that distance at a combined speed of 700 miles an hour go those 3oo yards in less than one second.

But this German wouldn’t break off the attack before he had passed me. He was too smart and had too much guts for that. He knew he’d lose me if he did that. So the best I could do was to turn as he passed me and come alongside of him again. We did that for about fifteen minutes, reversing turns from head-on attacks. I couldn’t outguess him and he couldn’t outguess me.

We were at a stalemate in this duel of ours. For every thrust there was a parry, but I knew that all I had to do now was to stick with him until he ran out of ammunition, and that’s what happened. He used up his last bullets and then he went home, and I climbed with a great surge into the sky, feeling I would like to find a cloud and get out and dance on it.

That fight was, perhaps, the most critical I have ever fought. I have had bigger triumphs, easier ones, but this one taxed every last bit of me. It showed me what I had learned and it taught me what I was. After it I felt there was no German alive anywhere who could keep me from killing him when I had an even break in the fight; or if the breaks went against me and he got them all, I felt I could keep him from killing me.

I had felt this way several times before, but now for the first time I knew the reasons. It was a handy feeling to have, for about a month after that the picture changed for the American fighter planes. They were taken off the defensive and put on the offensive and told to go out and clobber down every German that showed his face.