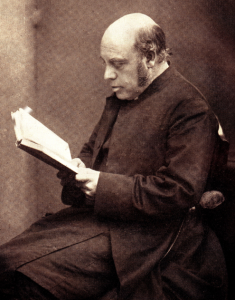

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Leaders in the Northern Church: Sermons Preached in the Diocese of Durham by the late Joseph Barber Lightfoot, Lord Bishop of Durham (published 1907). This sermon was preached at the Millenary Festival of the Parish Church of Chester-le-Street on July 18, 1883.

A thousand years in thy sight are but as yesterday.

Psalm xc. 4.

A thousand years! What a crowd of associations are suggested by these words. What thronging memories of the past, what solemn reflexions on the present, what anxious hopes and fears for the future. A thousand years! What changes have taken place in this long lapse of time. How many nations have risen and fallen; how many dynasties have flourished and decayed; how many tongues have died out; how many once famous names have been forgotten.

A thousand years ago! We cannot by any effort of our imagination realise the condition of England at this remote period. Without a literature, without a parliament, without any of those developments, social, political, and intellectual, which make her what she is. A thousand years ago! When the pirate ancestors of the Conqueror had not yet left their Scandinavian home to settle on the shores of France, and the invasion of England by Norman William was still an event of the remote and unforeseen future. A thousand years ago! When the half-legendary hero of our childhood, the great and wise Alfred, poet, scholar, warrior, legislator, was ruling as king over this land – the one man who deserves to be regarded as the founder of our English literature, the unifier of our English territory, the chief author of our English greatness.

Is it not a striking thought that the opening of the millennium, which we this day commemorate, should have synchronized with the reign of a sovereign who more than any other in the long roll of our history combined in himself, in the fullest measure and in perfect harmony, all those features which are truest and best in the English character? Yes, as we give thanks to God this day for His manifold goodness to ourselves, to this parish, to the Church of this land, let us not forget to mingle with these our thanksgivings the gratitude due to His signal mercy, who in the hour of England’s sorest need, when the land was invaded by foreign foes, and darkness – spiritual, intellectual, and social – was gathering fast and thick upon it, raised up this great deliverer, as great as he was wise, as pious and devout as he was great, the noblest type of Englishman who has ever trod this soil. Who can say what would have become of England if Alfred had never been?

A thousand years to man is everything, and more than everything – far transcending the reach of his aims, eluding even the grasp of his imagination. It is, we might almost say, a representation of eternity to him. But to God it is nothing at all. A single day from sunrise to sunset, a night watch come and gone instantaneously for the unconscious slumberer, a fleeting cloud, an arrow’s flight, a twinkling of an eye – these images are powerless to describe the nothingness of all measures of time to Him for whom is no before or after, before whose eyes the infinite past and the infinite future are spread as a map, to whom there is one eternal Now.

This contrast, which engages the Psalmist’s thoughts in the text, will be impressed upon our minds by the festival of today, the contrast between the infinite and the finite, between the eternal mind, the abiding purpose of God, and the fleeting aims, the varying moods, the ever-changing fortunes and vicissitudes of man. For today we stand face to face both with the transitory and with the abiding. With the transitory; for as we review this thousand years of history we are reminded how all things human come and go like the shadow of a dream. With the abiding; because through all these changes of civil, of intellectual, of social life, one constant thread of a Divine purpose runs. One institution has survived the wrecks of ages. The Church of Christ is older than the English monarchy, than the English nation, than English law or English literature. The Church of Christ is the same in its essential character now as ever, will be the same to the end of time. It is subject to vicissitudes many and various; it has its triumphs and its defeats; it has its seasons of error and sloth and incapacity and degradation, as well as its seasons of high enterprise and deep spirituality and energetic zeal; for it is administered by human agents. But throughout there has been a sustaining power not of earth; a life-germ which no antagonism of foe, and no recklessness of friend, could extinguish – ever reviving, ever asserting itself, ever breaking out in fresh developments. This power is called in Holy Scripture “the Word of God.” “The voice said, Cry; and he said, What shall I cry? All flesh is grass, and all the goodliness thereof is as the flower of the field. The grass withereth; the flower fadeth; but the Word of our God shall stand for ever.”

We recall the story of the Book of the Gospels, Cuthbert’s own book, which the monks of Lindisfarne carried with them in those wanderings that led them at length to the very spot where this day we worship. They set sail for Ireland; a storm arose; the book fell overboard and was lost; they were driven back to the English coast; disconsolate they went in quest of the precious volume; for a long time they searched in vain; but at length (so says the story) a miraculous revelation was vouchsafed to them, and following its directions they found the book on the sands, far above high-water mark, uninjured by the waves nay, even more beautiful for the disaster.

Does not this story well symbolize the power of the Eternal Gospel working in the Church? Through the carelessness of man it may disappear amidst the confusion of the storms; the waves may close over it and hide it from human sight. But lost – lost for ever – it cannot be. It must re-assert itself, and its glory will be the greater for the temporary eclipse which it has undergone. Yes, the fate of this Lindisfarne volume of the Gospels is a true type of the undying Word of God, of which it is the written expression.

We celebrate today the millenary festival of the foundation of this church. But we must go two centuries farther back still, if we would trace its history to the true source. We place ourselves in imagination twelve centuries ago. We are in a lonely, barren, storm-lashed island off the Northumbrian coast. Cuthbert, the saintly ascetic, has retired thither to his solitary cell retired, as the event proved, to die. He is there alone with the sea-birds, his cherished companions. For five days the storm prevents all communication with him. Then he is visited by a small company of his monks from Lindisfarne. The end is now at hand. Herefrid, the abbot, is admitted alone. He receives the last instructions of the saint. It is somewhere about midnight, the hour of prayer. The departing saint is strengthened for his long journey with the Communion of the body and blood of Christ. Then raising his hands to heaven “he sped forth his spirit” – these are Herefrid’s own words – “into the joys of the heavenly kingdom.” Herefrid announced his departure to the brethren outside. They were singing the psalm which has justly taken such a prominent place in our service today – the psalm, as it so happened, which was appointed in due order for the service of that night, Deus, repulisti nos, “O God, Thou hast cast us out and scattered us abroad, O turn Thee unto us again: O be Thou our help in trouble; for vain is the help of man.” One of the monks mounted the high ground above the cell and held up two lighted torches – one in either hand – the preconcerted signal; and the brothers in far-off Lindisfarne knew that their spiritual father was gone. They too at this very time were chanting the same psalm, Deus, repulisti nos. Thus the wail of the Israelites of old was flung across this lonely sea to and fro from island to island – the unpremeditated but fit funeral dirge for him whose destiny in death was stranger than his destiny in life.

The story is recorded by Bede, who heard it from Herefrid himself. Herefrid added that the prophetic import of these words was fulfilled shortly after, when several monks were driven forth from Lindisfarne by some perils which assailed them, but God soon built up His Jerusalem again, and restored their scattered remnants. Yet neither Herefrid nor Bede could have foreseen the far stranger fulfilment which was in store long after they were laid in their graves. We may well imagine that the monks of Lindisfarne, as centuries later they wandered to and fro – from north to south, and from sea to sea – bearing the body of S. Cuthbert, knowing not from night to night where they might lay their heads, recalled again and again the Psalmist’s wail which had wafted the saint’s spirit to the skies, Deus, repulisti nos; and when at length they settled in your Chester-le-Street, they would remember Bede’s narrative, and, again in the words of the Psalmist, break out into thanksgiving, “The Lord doth build up Jerusalem, and gather together the outcasts of Israel.”

I have spoken of a thousand years, and again of twelve hundred years; and I have asked you to throw yourselves back in imagination through these long periods, that you may trace the train of events which, in God’s providence, has led to the festival of today.

But why should you stop here? God’s purposes in the chain of cause and consequence are not limited to ten or twelve centuries. I am reminded by the very name of this parish that long before Aidan preached, or Cuthbert was born, God in His far-reaching providence was laying the foundations on which the future Church of Christ in this place should be built. Christ came in the fulness of time came when all things were prepared for His coming. Not the least important instruments in this preparation were the Romans. Is it not a significant fact that the Evangelist commences his narrative of Christ’s human birth and life with the mention of Caesar Augustus? If we were required to state briefly the services rendered by the Romans as preparing the way for the Gospel, we should say that they were twofold, order and intercommunication. The Romans reduced the nations to order; they consolidated the civilised world; they united it under one rule; they gave it a settled government; they placed it under the administration of justice; they enforced obedience to the laws. This discipline of the world they exercised as a great military power. Again, they provided means of communication between provinces far and wide; they were the greatest road-makers that mankind has ever seen; thus they opened out the known world to travellers. What inestimable benefits these two results of Roman civilisation were to the Apostles and first preachers of the Gospel I need not say. But these very functions are embodied in the name of this place. Chester, Castra, the military camp, with its regularity and its discipline, represents the one characteristic, the principle of order. The second part of the name, the Street, the Roman road which ran through this place, embodies the other, the benefit of intercommunication. So, then, in the name of your parish, you have a speaking lesson of God’s far-seeing designs; and it will give fulness to your thanksgiving today if you remember, not only what God has done for you since Christianity was first preached in these parts, but also how, long centuries before, the soil was prepared to receive the seed from the hand of the Divine husbandman.

From the thronging historic memories which this festival more directly recalls, we may single out two great lessons – the influence of a great personality and the discipline of a great public disaster.

1. What was it that won for Cuthbert the ascendancy and fame which no Churchman north of the Humber has surpassed or even rivalled? He was not a great writer like Bede. He was not a first preacher like Aidan. He founded no famous institution; he erected no magnificent building. He was not martyred for his faith or for his Church. His episcopate was exceptionally short, and undistinguished by any event of signal importance. Whence then this transcendent position which he long occupied, and still to a certain extent maintains?

He owed something doubtless to what men call accident. He was on the winning side in the controversy between the Roman and English observances of Easter. Moreover, the strange vicissitudes which attended his dead body, served to emphasize the man in a remarkable way.

But these are only buttresses of a great reputation. The foundation of the reverence entertained for Cuthbert must be sought elsewhere. Shall we not say that the secret of his influence was this? The “I” and the “not I” of S. Paul’s great antithesis were strongly marked in him. There was an earnest, deeply sympathetic nature in the man himself, and this strong personality was purified, was heightened, was sanctified by the communion with, the indwelling of, Christ. His deeply sympathetic spirit breathes through all the notices of him. It was this which attracted men to him; it was this which unlocked men’s hearts to him. We are told that he had a wonderful power of adapting his instructions to the special needs of the persons addressed. He always knew what to say, to whom, when, and how to say it.

This faculty of reading men’s hearts sympathy alone can give. And Cuthbert’s sympathy overflowed even to dumb animals. The sea fowl, which bear his name, were his special favourites. There is a pleasant story told likewise, how on one occasion, being hungry and having no food at hand, he descried an eagle and bade his companion follow it. The attendant returned with a large fish which the eagle had caught in a river. He rebuked his companion, bade him cut the fish in two, and take half back, that God’s kindly messenger, the eagle, might not be without a dinner. Other tales too are told – perhaps not altogether legendary – which testify to his sympathy with, and his power over, the lower creation. We are reminded by these traits of other saintly persons of deeply sympathetic nature, of Hugh of Lincoln followed by his tame swan, of Anselm protecting the leveret, of Francis of Assisi conversing familiarly with the fowls of the air and the beasts of the field as with brothers and sisters.

But if the “I” was thus strong and deep, the “not I” was not less marked – “Not I, but Christ liveth in me.” His fervour at the celebration of the Holy Sacrament manifested itself even to tears. “He imitated,” says Bede, “the Lord’s Passion which he commemorated, by offering himself a sacrifice to God in contrition of heart.” He died with Christ, that he might live with Christ. We may see many faults in this saint – faults more of the age than of the man. Our reverence for him does not require us to approve the religious ideal which drove him to many years of solitary seclusion, or the religious temper which branded as the worst of heretics those who observed Easter as their forefathers had observed it. But these errors may well be condoned in one, of whom it can be truly said that “his life was hidden with Christ in God.” As we read Bede’s life of him, amidst much credulous superstition we are struck with the entire absence of that taint of Mariolatry which poisoned the well-springs of a later theology. God in Christ, Christ in God – this is all in all to him.

2. But let me turn for a few moments to the other great lesson which the memories of today suggest, – the discipline of a period of disaster. The Israelite sojourn in the desert – the wanderings to and fro, the privations, the trials, the defeats – this is the prototype of many a chapter in the history of churches, when God has led His people into the wilderness – not to crush them, not to annihilate them, but in the prophet’s words, “to speak comfortably” to them, to chastise with a fatherly chastisement,to amend, to purify, to strengthen, to train for a greater future. So it was with these Lindisfarne monks. We may smile at their credulity. We may contemn their ignorance. We may scout their old-world superstitions. But for those who have eyes to see and ears to hear, there is a sublimity of heroism in the faith, the constancy, the unfailing courage of these outcast wanderers, carrying about the body of their spiritual ancestor, “perplexed but not in despair, persecuted but not forsaken, cast down but not destroyed,” reaching at length their goal and finding in Durham a greater Lindisfarne – a sublimity of Christian heroism which no superficial errors can hide.

We meet together today with no common feelings of joy and gratitude. We pour out our hearts in thanksgiving to God for His manifold and great mercies to the Church in this place during the thousand years past. We beseech Him to accept this fabric, renovated and adorned, as a feeble offering of His grateful servants. We supplicate Him to look favourably upon us in the years to come. The future is hidden from our eyes. We know not – we cannot know – what the next millennium, the next century, even the next decade, will bring forth. We look forward with the brightest hopes indeed, but not without many grave anxieties also. It may be that in some form or other He will try us again, will lead us once more into the wilderness, will renew once more the discipline of the Lindisfarne wanderers. If such a trial should await us, then may we, with our higher enlightenment and our larger knowledge, not fall short of their patience and courage and hope. May our faith find expression once more in the old familiar words of the Psalmist, full of power and of pathos, which in successive generations have touched and solaced the hearts of mourners over the open grave: “Lord, Thou hast been our refuge from one generation to another,” “Thou art God from everlasting and world without end;” “A thousand years in Thy sight are but as yesterday;” “When Thou art angry, all our days are gone;” “Turn Thee again, O Lord, at the last; and be gracious unto Thy servants,” “Deus, repulisti,” “Domine, refugium.”

5