John N. Edwards’ Noted Guerrillas (1877)

Part of a series of history books that belong in every American’s library. Recommendations welcome.

The difficulty with Edwards’s Noted Guerrillas is not that the story it tells is untrue, but that it is almost true. From the Tate House Fight where William Clarke Quantrill’s career was nearly strangled in its cradle to his seemingly-miraculous flight following the Lawrence Massacre, events spring to life from Edwards’ pages in a detail that betrays their origin in eyewitness testimony.

The deeds of Quantrill, of Jesse and Frank James, of Jim and Cole Younger, of Bloody Bill Anderson and of George Todd all reinforce what we know of the violence that created such terror on the Kansas-Missouri border in those years. And yet the very name Edwards attaches to the guerrilla captain itself is wrong. Edwards calls him throughout the book “Charles William Quantrell,” mixing the alias of the man with his true name as he mixes the fantastic deeds of Quantrill’s men with their true ones.

John Newman Edwards was, from birth to death, a Southern man. Born in Virginia, he moved to Lexington, Missouri, right in the center of Quantrill’s later stomping grounds, at the age of fourteen. When the war broke out, Edwards joined Joseph O. Shelby’s Confederate Missourians, serving him as adjutant and finally as a major during Price’s 1864 raid through Missouri, which his book describes in detail.

Following the war, he followed Shelby to Mexico, authoring two books there that recount the exploits of the unrepentant rebel general and his Iron Brigade. Edwards returned to his adopted state in 1867 where he founded or edited a handful of Missouri newspapers including the Kansas City Herald. These papers he used to call other unreconstucted men back into politics, and to spread the fame and myth of Quantrill, the James Gang, and the Younger Brothers nationwide. Noted Guerrillas, written in 1877 and which pursues those same ends, grew up as an extension of Edwards’s day job.

After two brief chapters which differentiate the American guerrilla from his Spanish and Italian counterparts, Edwards jumps immediately into the tale of Quantrill’s conversion from innocent into martyr for the South’s honor. In this tale, Quantrill and his older brother, passing through Kansas on their way west, are beset by Jayhawkers. The older brother is murdered, while “Charles,” left for dead, lies near his corpse, retaining barely enough strength to drag himself down a nearby riverbank to quench his thirst and back up to continue his lonely vigil. Rescued by a kindly Indian four days later, Quantrill convalesces at the man’s home for nearly a year.

Once recovered, Quantrill enters Lawrence under the alias “Charley Hart,” joins the Jayhawkers under Senator Jim Lane, then rises in their ranks through martial excellence while quietly killing off 30 of the 33 men who murdered his brother. Quantrill, through an elaborate ruse, entices the final three abolitionists into a clandestine mission to free slaves from the home of Morgan Walker, a wealthy Missouri farmer. Warning Walker of the coming “attack,” Quantrill leads his own men to a well-deserved death at the hands of noble Missourians protecting their property. Thus did Quantrill prove his undying loyalty to Missourians and all that they stood for.

The tale is not only of Quantrill, but it is Quantrill’s own tale, the one he made up to ingratiate himself with Missourians when he took over the leadership of a small band of fighters that would grow into the scourge of the Kansas border and the western half of Missouri. His boasts, like the dry bones of Ezekiel’s biblical vision, joined together and grew flesh as that leadership and his reputation grew. Eventually they rose to life, a fully-formed myth of the living man.

The utter falsehood of Quantrill’s biography is illustrated in William Elsey Connelley’s Quantrill and the Border Wars. Meticulously footnoted – possibly because Edwards’s book lacks footnotes utterly – the latter account picks Quantrill’s tale apart statement by statement. Connelley describes Edwards’s version of Quantrill’s early life thusly: “Major Edwards believed what he wrote, for he was an honest man.” Edwards’s story of Quantrill and his men is a tale told by an honest man and a good writer who very much wished it to be true, but perhaps did not look very far to see where it was not.

In full accord with his purpose, Edwards’s generic guerrilla held Quantrill’s attributes, while his Jayhawking nemesis displayed different qualities:

[The Jayhawker] would fight when he had to fight, but he would not stand in the last ditch and shoot away his last cartridge. Born to nothing, and eternally out at elbows, what else could he do but laugh and be glad when chance kicked a country into war and gave purple and fine linen to a whole lot of bummers and beggars?

The Missouri guerrilla, the epitome of the characteristics the Kansas man lacked, fought to the last man, asked no quarter, and willingly faced long odds wearing a smile that usually masked the pain of a personal loss to the Jayhawkers.

Even “Bloody” Bill Anderson can be understood in this model, for he probably would have “pursued his placid ways in peace” had not Union soldiers arrested his sisters and thrown them into a makeshift jail. To add injury to insult, those soldiers then allegedly undermined the building, causing it to collapse and kill one of the women while maiming another. Left out is the fact that Anderson’s sisters had been arrested precisely because they were Anderson’s sisters, caught aiding and abetting a famous guerrilla.

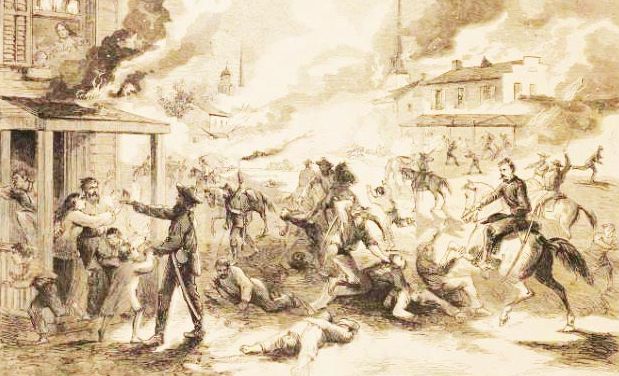

The undermined building is one example of how Edwards’s book is at its heart a morality tale, one that found a willing audience in the South while building the careers of gangsters and bank robbers. Even those bank robbers, like one man who liberated $8,000 in greenbacks from a Lawrence bank during the famous raid, brought their trophies to Missouri only “for distribution among the widows and orphans of war”. Like the Dukes of Hazzard, Missouri Partisan Rangers were “just good old boys, never meanin’ no harm.”

The story of the Tate House Fight is one example of almost truth – Edwards describes it taking place on February 20, 1862, when in fact it occurred in late March. Edwards has also Colonel Charles R. “Doc” Jennison leading the companies who surrounded Quantrill’s men inside the farmhouse, though the Kansas Seventh and their commander slept that night in Leavenworth, Kansas, dreaming about the orders they expected would shortly send them off to New Mexico. Edwards also informs us that, “not a man of Quantrell’s[sic] command was touched” in the fight, while the Union Blue lost 18 men killed and suffered almost 30 injured. In reality, while the guerrillas sustained a mere one man killed, they failed to kill a single Union soldier.

Edwards’ numbers consistently slant that way – the guerrillas lose a man or two while carrying home bullet wounds and Union uniforms by the dozen. They kill 29 of 32 soldiers here, 8 of 10 there. Quantrill even kills a large number of “Jennison’s Men” in Harrisonville, Missouri, in the fall of 1862 – though Jennison was out of the service at the time and his former command was serving under General Ulysses S. Grant in Mississippi. Quantrill fights the men of Jennison’s Fifteenth Cavalry in 1861, though that regiment will not be established until 1863, after Quantrill’s hoorrible, masterful raid on Lawrence. Still, there is no doubt that Quantrill and his followers killed a lot of Union men: just ask General James Blunt’s regimental band. And Edwards’s account of those killings is almost true.

Almost true as well are Edwards’s revisionist descriptions of the relations of black Missourians with the partisans. In one tale, Cole Younger is hidden and rescued from soldiers by “a former slave, but more a confidant than a slave”. This old woman bravely faced down “the gaping muzzles of a dozen guns” held to her head by Union soldiers in order to save Younger’s hide. The old matron is then continually persecuted by men in blue until she finally dies at their hands, “true to her people and her cause”.

In the episode of the massacre of passengers aboard the steamer Sam Gaty near Lexington, all the blacks aboard are shot (or shot at), not because they were contrabands escaping to Kansas as eyewitnesses aboard the boat claimed, but because they were “in Federal uniform”.

But the fact that a story is almost true does not make it false. Even with its inaccuracies it may be more “true” than contemporary accounts. One such instance is the reason I chose this book. Noted Guerrillas contains an account of the killing of Phillip Bucher by Union officer George Hoyt which I had seen repeated in a number of other pro-South accounts, including one written in the past decade.

In describing the period leading up to the August 1863 raid on Lawrence, Edwards informs us that “the strife in Jackson County had been particularly savage of late”. Tucked into a virtual laundry list of recent crimes that had to be avenged through the spilling of abolitionist blood was this one: “Capt. Hoyt, another Kansas officer, rode into Westport one day, took Phillip Bucher from his wife and children, marched him out on the commons, made him kneel down, and shot him”.

There are some true facts here. In August 1863, Hoyt was a captain, and was leading raids into Jackson County, Missouri, on a regular basis under the auspices of the Kansas Red Legs. But a small problem, like in the other almost-true stories, is that while then-second lieutenant Hoyt killed Bucher, he did so in December of 1861, not in the summer of the Lawrence raid.

Edwards’s account is not the only account of this killing. Shortly after Hoyt killed Bucher, an anonymous soldier sent a letter to an Ohio newspaper describing the encounter. In that letter, published by the paper under the title “The Killing of a Rebel,” Bucher is described as a ‘notorious’ Confederate fleeing from Hoyt’s men, who were loading a wagon. As Bucher darted out of a nearby house, Hoyt shot him through the heart to prevent his escape. The story also notes that Hoyt shot while he sat atop Bucher’s own horse, which Hoyt had captured during a prior encounter and for which act Bucher had threatened Hoyt’s life. The Union version is, in every detail, almost the opposite of Edwards’s.

And yet buried in the bowels of the Kansas Historical Society archives lies a hand-written, five page biography of a murdered Free State man named Major David Starr Hoyt, composed around 1870 for a genealogical work on the Hoyt family. In the final paragraph of this biography, a paragraph which did not make the publication, its author reveals that the 1856 death of Major Hoyt was avenged in Westport by a “near relative” and that the guilty man died with a description of that murder on his lips.

The man fingered as the murderer is Phillip Bucher. The man who penned the biography is George Hoyt. If Bucher truly died making such a confession, it is certain that Edwards’s description of events is closer to the historical truth than the one published in the papers. Rather than being the hero of a random violent encounter, Hoyt went to Westport, his soldiers in tow, to kill Phil Bucher. Missourians, not knowing why, understandably credited that act to the account on which they hoped to collect, with interest, in Lawrence.

To the person who already knows the history of William Clarke Quantrill and his Partisan Rangers, Edwards’s Noted Guerrillas provides valuable insight into the men of Quantrill’s command, as well as their motives and methods. It describes their hopes, or at least describes them as they hoped to be remembered.

As a compass is most valuable when one can find his position on an accurate map, Edwards’s almost-truths can help us find our way to a good number of the real ones. But if relied upon alone as a history of the people and times, it is a very poor history, just as the same compass can be of limited utility – and even misleading – to one who is utterly lost.

4