Editor’s note: The following is extracted from History, by Bernadotte Perrin (published 1912).

It was the attempt of the Oriental Persian Empire to conquer the Aegean basin which engaged the Homeric genius of Herodotus; Thucydides depicts the struggle of Athens to maintain her empire of this Aegean basin, and he does it as a contemporary and participant. An imperial democracy was a new thing in the world’s experience, as was also the historical treatment of contemporary events. Current events had been chronicled in time-relations merely by Hellanicus, but Thucydides was the first to apply to them the laws of cause and effect, and, whatever his excellences or defects, he was the founder of historical science as we now understand it, the creator of historical criticism, the discoverer of its laws, and the first teacher of the art of writing history. He whom many hold to be the greatest modern historian of antiquity, Eduard Meyer, calls him the incomparable and unequaled teacher of this art, but there are strong voices of dissent from such high praise. Those who dissent often fail to consider sufficiently the exceedingly narrow limits which Thucydides imposed upon himself; and those who agree with and echo the praise are often blind to the inadequacies of Thucydides, even within his self-imposed limits. Professor Bury, in his Harvard Lectures, seems to draw the lines with dignity and justice.

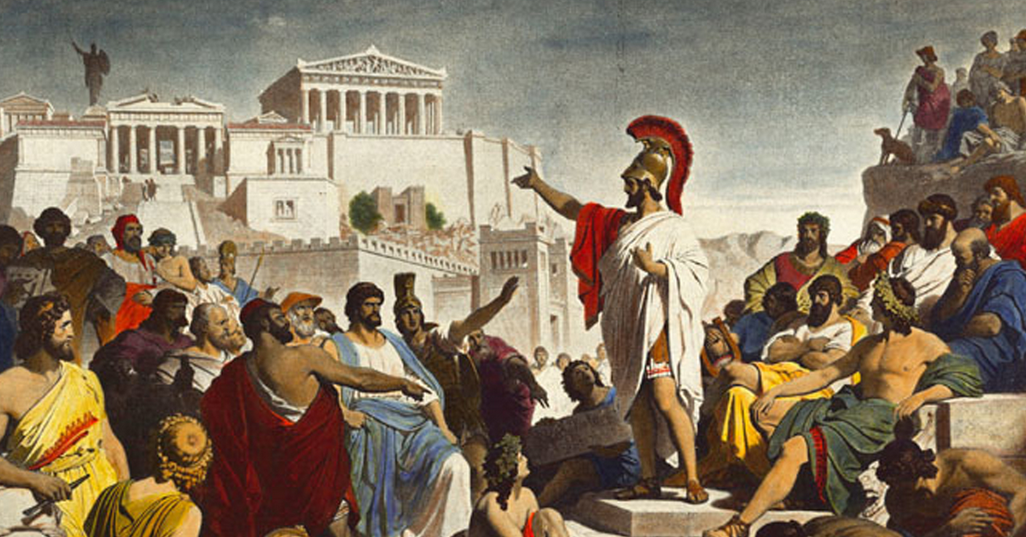

“Thucydides, an Athenian,” so begins the work, “wrote the history of the war in which the Peloponnesians and Athenians fought against one another. He began to write when they first took up arms, believing that it would be great and memorable above any previous war. For he argued that both states were then at the full height of their military power, and he saw the rest of the Hellenes either siding or intending to side with one or the other of them. No movement ever stirred Hellas more deeply than this; it was shared by many of the barbarians, and might be said even to affect the world at large.” He began to write, that is, when it broke out, the history of a great war, not a history of Athens or of the Peloponnesian states; not a history of Hellenic culture or of Athenian democracy; not a description of unknown countries, except as absolutely necessary, or of unknown peoples and customs; not personal descriptions or anecdotes of private life – Ion of Chios or Stesimbrotus of Thasos could do that – but a war-history. And even in writing a war-history his aim would not be to please and entertain, as Herodotus did, but to instruct. “If he who desires to have before his eyes a true picture of the events which have happened, and of the like events which may be expected to happen hereafter in the order of human things, shall pronounce what I have written to be useful, then I shall be satisfied. My history is an everlasting possession, not a prize composition which is heard and forgotten.”

Who is it that speaks with this new note of self-repression and utilitarian purpose? A man who, at the time of which he speaks, was about thirty-five years old, a citizen of Athens, who belonged by descent to a princely family of Thrace, as Cimon had, and still possessed rich estates in that country. He was highly educated after the manner of the best Sophists, and doubtless found Anaxagoras an intellectual father, as Pericles did. He was emancipated from the undue authority of tradition and custom, and given to logical analysis and criticism. His intellectual processes, that is, were distinctly modern. That he took active part in public life before the year 424 B.C., may be safely inferred from the fact that in that year he was made one of the ten Strategi, whose office was the highest under the Empire. Assigned to command on the coast of Thrace, he failed to prevent Brasidas from capturing Amphipolis, the northern jewel of the Empire, and was in consequence banished on pain of death. His purpose to write a history of the war, however, was not thwarted by this misfortune. Indeed, it may rather be inferred that he had now the leisure, as he had always had the means and the disposition, to continue the history which he had begun at the outbreak of hostilities in 431. “The same Thucydides of Athens,” he writes in V, 26, “continued the history up to the destruction of the Athenian Empire. For twenty years I was banished from my country after I held the command at Amphipolis, and associating with both sides, with the Peloponnesians quite as much as with the Athenians, because of my exile, I was thus enabled to watch quietly the course of events, and I took great pains to make out the exact truth.” It is safe inference that this banished Athenian spent much time on his estates in Thrace, and that he traveled much, where it was allowed him to travel, in the prosecution of his inquiries. He returned to Athens in 404, after the war was over, and began to put his material into final form. Eight years, perhaps, were employed in this task, when death overtook him, before its completion. His work, unlike that of Herodotus, is therefore a fragment. Seven of the twenty-seven years during which the Athenian Empire was fighting to maintain itself find no record in what has come down to us from Thucydides, and the last of the eight books into which the extant material has been judiciously divided by ancient critics plainly lacks the author’s final revision. But three distinct manners are plainly to be seen in what we have of the work – a philosophic manner, as in the first book; an annalistic manner, as in books two, three, four, and five (resumed again in the incomplete eighth book); and an episodic manner, as in the story of the campaign at Pylos and Sphacteria, of the siege of Plataea, or the major story of the Sicilian expedition. All three manners are alike characterized by a dramatic method which projects events and persons as it were upon a stage, and leaves them to act out there the Fall of the Athenian Empire. Apparently, but only in appearance, the author pronounces few judgments on men and events, leaving them for the judgment of his readers. His detachment, in all three manners, has certainly never been surpassed. An oligarch in political convictions, to whom an extreme democracy was “manifest folly,” he yet gives us a sympathetic and spirited picture of the Athenian democracy under Pericles, in which inherent weaknesses are not suffered to obscure pure and lofty ideals. An Athenian to the core, he never belittles Spartan nobility and greatness, but gives us in his portrait of Brasidas a character hardly second to that of Pericles. An admirer of the Athenian Empire, a participant in its honors, and stimulated to literary activity by its splendor, as Herodotus had been by that of the Persian Empire, he uncovers with relentless hand the greed and cruelty which marked its growth, culmination, and decline. In historical philosophy our best modern historians may well surpass him, especially as the appreciation of economic laws is a modern acquisition. But in episodic power, and, above all, in personal detachment from the characters and events of his story, it is no exaggeration to say that he remains unsurpassed.

The philosophic manner of Thucydides may be best illustrated by a brief outline of the general introduction to his narrative of the war formed by his first book, which was clearly written after the war was over, i.e. after 404 B.C.

A brief prooemium emphasizes the greatness of his theme. The empire of the Hellenic world was at stake. The earlier history of this Hellenic world is rapidly reviewed in the clear light of reason, which uncovers the falsity of legend and romantic oral tradition, and a new standard is set for the treatment of ancient and recent history. Coming to the treatment of contemporary and current history – a new art entirely – he says: “Of the events of the war I have not ventured to speak from any chance information, nor according to any notion of my own; I have described nothing but what I either saw myself, or learned from others of whom I made the most particular inquiry” (i, 22, 2). He catches oral tradition, therefore, in the making, and not, as Herodotus did, after a generation or two of romantic expansion or partisan distortion. The war which he is to describe had a deep, underlying general cause – the growth of the Athenian Empire into formidable dimensions; and also immediate and special occasions, such as the Athenian alliance with Corcyra and the siege of Potidaea. Both the immediate occasions and the general cause are treated at length, and then more briefly the various diplomatic steps which preceded the actual declaration of war by Sparta and her Peloponnesian confederacy. This is a philosophical method, and, though new in the world then, it can hardly be improved upon now. Various economic relations may be brought into prominence in setting forth the general underlying cause of the war, as Mr. Cornford has lately so well done, but, remembering that economic science is a development of the nineteenth century, historical students may well rest satisfied with the elaborate introduction of Thucydides. Contrast the semi-playful tone with which Herodotus introduces his story of the Persian Wars. Some Phoenicians carried off Io from Argos, and in retaliation some Greeks carried off Europa from Phoenicia. “Bearing these things in mind,” Alexander the son of Priam carried off Helen, and the Greeks were fools enough, according to the Persian view, to make a fuss about it and lead an army into Asia. Hence the enmity of the Persians. It is true that as regards the initial outrage of the series the Phoenicians claim that Io was no better than she should have been, and followed them of her own free will. “Which of these two accounts is true,” says Herodotus (I, 5, Rawlinson’s translation), “I shall not trouble to decide. I shall proceed at once to point out the person who first within my knowledge commenced aggressions on the Greeks, after which a shall go forward with my history.” The difference between the artistic story-teller and the philosophical historian could not be made plainer.

The annalistic manner of Thucydides is often dry and tedious. But it is certain that even this manner is an advance upon its greatest exponent hitherto, namely Hellanicus; and the fact that Thucydides was obliged to establish his own system of chronology makes us charitable. It is easy for us, with our perfected calendar, to fix with precision the temporal relations of events. It was not easy for Thucydides to do so. Lists of archons, or other official personages, were used in different cities of Hellas to mark the time of past events, and Hellanicus had finally catalogued his events according to Athenian archons, a good standard certainly throughout the Athenian Empire. But, Thucydides objects (v, 20, 2), “whether an event occurred in the beginning, or in the middle, or whatever might be the exact point, of a magistrate’s term of office, is left uncertain by such a mode of reckoning.” He therefore measured time by summers and winters, counting each summer and winter as a half-year, and established with infinite precision his initial year and event. In the fifteenth year of the peace which was concluded after the recovery of Euboea, the forty-eighth year of Chrysis the high-priestess of Argos, “Aenesias being ephor at Sparta, and at Athens Pythodorus having two months of his archonship to run, in the sixth month after the engagement at Potidaea, and at the beginning of spring, about the first watch of the night an armed force of Thebans entered Plataea,” and the war was on. This impresses us as a large apparatus for small resultant precision, since we can glibly say that at half-past four o’clock on the morning of the 12th of April, 1861 A.D., the first shot of our Civil War was fired. But since Thucydides had devised a system of chronology far superior to anything in use before him, it is small wonder that he makes much of it, and so becomes wearisome to us moderns, especially if the events which he chronicles seem to us, as many of them do, trivial. In relation to his theme, the behavior of the Athenian Empire under stress and strain of war, they can rarely be called trivial.

Of the third manner of Thucydides, which I have called the episodic, i.e. the manner in which he narrates the great episodes of the war, surely little need be said here, when so good a judge of narrative as Macaulay has pronounced his story of the Sicilian Expedition the “ne plus ultra of human art.” And time would fail to speak sufficiently here of his digressions, few in number, always logically connected with the main story, and always peculiarly telling from the fact that they seem a condescension on the part of one whose aim is far higher than merely to entertain. In Herodotus, the entertaining digression rises almost to the dignity of a main object; in Thucydides, it is a rare jewel in a severe setting. And yet how graceful and fanciful and altogether charming Thucydides can be, in spite of his scorn for the historical charmer, is to be seen in the digression which depicts the career of Themistocles after his ostracism (i, 135-138). Threading his way through the maze of legend which had accumulated about the figure of Themistocles after his departure from the better known parts of Hellas, Thucydides has not the heart to eliminate from his story certain most romantic features, and shows us in the scene at the palace of Admetus, King of the Molossians, an ability to follow and develop Homeric suggestions fully equal to that of Herodotus. It is like a smile upon a stern face.

On the speeches also in Thucydides the whole time now at our disposal might profitably be spent. A purely ornamental literary device in Homer and Herodotus has been lifted by him into a means for securing that personal detachment from the events and characters of his story which is the despair of all who come after him, and an apparent objectivity of presentation which is seen only in the best drama. These speeches range all the way from the brief hortatory appeal of a commander to his soldiers just before a battle, through the lengthy addresses of embassies to parliamentary assemblies, up to the matchless speech put into the mouth of Pericles ostensibly to commemorate the citizens of Athens fallen in battle during an uneventful year of the war, but really to set forth the historian’s broad conception of the imperial democracy of Athens, now fallen, and of the high ideals of that democracy’s first ruler and guide. “I have put into the mouth of each speaker,” says Thucydides (i, 22, 1), “the sentiments proper to the occasion, expressed as I thought he would be likely to express them, while at the same time I endeavored, as nearly as I could, to give the general purport of what was actually said.” As to Professor Bury’s interesting suggestion that the speeches composed in his more obscure manner contain more of what Thucydides thought was “proper to the occasion,” and those composed in his simpler manner more of “what was actually said,” we may be somewhat skeptical. And summing the matter up, we may say that in Thucydides, as in Herodotus, for all their deficiencies, there are certain high qualities, and more in Thucydides and higher than in Herodotus, which have never been surpassed by writers of history. How potent still is the influence of Thucydides may be clearly seen by those who know him in the pages of Mr. Rhodes’s great and now standard history of our Civil War.

(Continue to next chapter)