Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Our Soldiers, by W. H. G. Kingston (published 1863). All spelling in the original.

The Outbreak of the Crimean War

The settled resolve of the Russian Government to crush the power of the Turks, and to take possession of Constantinople, was the cause of the declaration of war by England and France against Russia.

The war became at once popular among the British people when the news was spread that a Russian fleet, consisting of six men-of-war and several smaller vessels, had darted out of Sebastopol, and, taking advantage of a dense fog, had entered the harbour of Sinope, where they found a Turkish squadron of eight frigates, two schooners, and three transports, totally unprepared for battle. Admiral Nachimoff, the Russian commander, fiercely attacked them, and though the Turks fought bravely, so great was their disadvantage, that in a few hours 5000 men were massacred, and every ship, with the exception of two, was destroyed. To prevent the recurrence of such an event, the allied fleets of England and France entered the Black Sea on the 3rd of January 1854. War was not officially declared against Russia till the 28th of March. The Guards and other regiments had, however, embarked early in February; first to rendezvous at Malta, and subsequently at Varna, on the Turkish shore of the Black Sea. The British troops, under Lord Raglan, amounted to 26,800 men of all arms; that of the French, under Marshal Saint Arnaud, to nearly the same number, 26,526; and there were also 7000 Turks, under Selim Pasha; making in all 60,300 men, and 132 guns, 65 of which were British.

On the morning of the 14th September, the fleet conveying this magnificent army anchored off the coast, near Old Fort, distant about eighteen miles south of Eupatoria. The first British troops which landed in the Crimea were the men of Number 1 company of the 23rd Welsh Fusiliers, under Major Lystons and Lieutenant Drewe. The landing continued during the whole day, without any casualties. The first night on shore the rain fell in torrents, and the troops, who had landed without tents or shelter of any sort, were drenched to the skin. On the following morning the sun shone forth, and the disembarkation continued. No enemy was encountered till the 19th, when two or three Russian guns opened fire, and a body of Cossacks were seen hovering in the distance. The Earl of Cardigan instantly charged them, and they retreated till the British cavalry were led within range of the fire of their guns, when four dragoons were killed and six wounded,—the first of the many thousands who fell during the war.

The evening of the 19th closed with rain.

Battle of the Alma

Wet and weary the allied troops rose on the morning of the 20th September of 1854, to march forward to the field of battle. On their right was the sea, on which floated the British fleet; before them was the river Alma, down to which the ground sloped, with villages, orchards, and gardens spread out along its banks. “On the other side of the river, the ground at once rose suddenly and precipitously to the height of three or four hundred feet, with tableland at the top. This range of heights, which, particularly near the sea, was so steep as to be almost inaccessible, continued for about two miles along the south bank, and then broke away from the river (making a deep curve round an amphitheatre, as it were, about a mile wide), and then returned to the stream again, but with gentler slopes, and features of a much less abrupt character.” The road crossed the river by a wooden bridge, and ran through the centre of the valley or amphitheatre. Prince Menschikoff had posted the right of his army on the gentler slopes last described, and as it was the key of his position, great preparations had been made for its defence. About half-way down the slope a large earthen battery had been thrown up, with twelve heavy guns of position; and higher up, on its right rear, was another of four guns, sweeping the ground in that direction. Dense columns of infantry were massed on the slopes, with large reserves on the heights above. A lower ridge of hills ran across the amphitheatre, and at various points batteries of field-artillery were posted, commanding the passage of the river and its approaches. In front of this part of the position, and on the British side of the river, was the village of Borutiuk.

On their left, close to the sea, the acclivities were so abrupt that the Russians considered themselves safe from attack. The river, which ran along the whole front, was fordable in most places, but the banks were so steep, that only at certain points could artillery be got across. A numerous body of Russian riflemen were scattered among the villages, gardens, and vineyards spread along the banks. The Russian right was protected by large bodies of cavalry, which constantly threatened the British left, though held in check by the cavalry under Lord Lucan. The right of the allies rested on the sea, where, as close in shore as they could come, were a fleet of steamers throwing shot and shell on to the heights occupied by the Russian left.

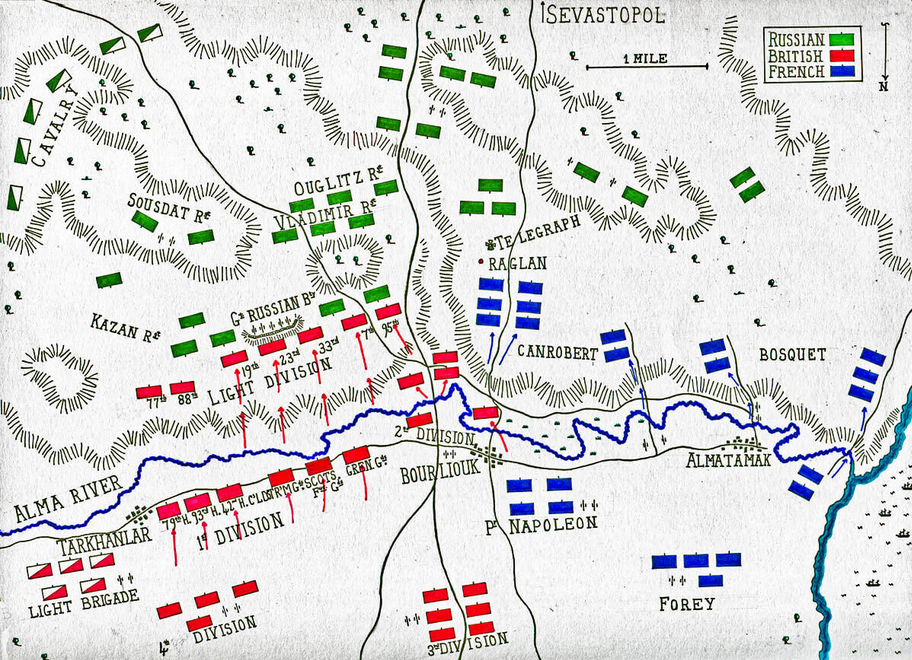

“At about eleven a.m. the allied armies advanced, the whole front covered by a chain of light infantry. On the extreme right, and about 1500 yards in advance of the line, was the division of General Bosquet; next, on his left, was that of General Canrobert; then the Prince Napoleon’s, with General Forey’s in his rear, in reserve. The English then took up the alignment, commencing with the 2nd division (Sir De Lacy Evans), then the light division (Sir G. Brown), and, in rear of them, the 3rd and 1st divisions respectively—the whole in column; Sir G. Cathcart, with the 4th division, being in reserve on the outward flank; the English cavalry, under the Earl of Lucan, considerably farther to the left, also protecting the exposed flank and rear.”

The French advancing, gained the heights, took the enemy somewhat by surprise, and almost turned his left. He then, however, brought forward vast masses of troops against them, and it became necessary for the British more completely to occupy them in front.

The two leading English divisions (the light and 2nd), which had advanced across the plain in alignment with the French columns, on coming within long range of the enemy’s guns deployed into line (two deep), and whilst waiting for the further development of the French attack, were ordered to lie down, so as to present as small a mark as possible. The Russian riflemen now opened fire, and the village burst into flames. Lord Raglan, with his staff, passing the river, perceived the position of the enemy on the heights he was about to storm. He instantly ordered up some guns, which, crossing the river, opened fire, and afterwards moving up the heights, harassed the Russian columns in their retreat.

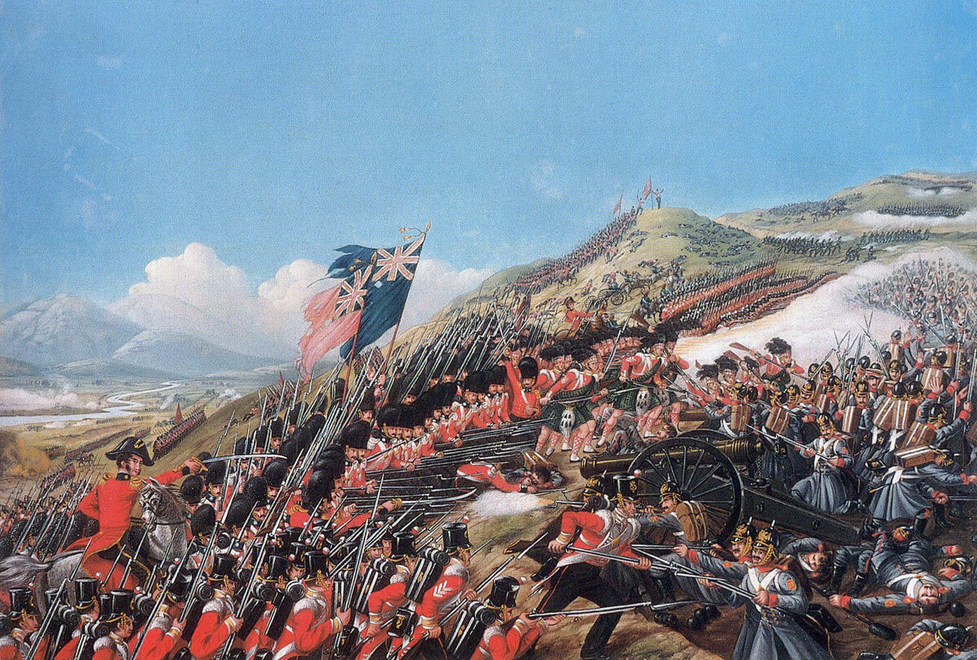

Now, with skirmishers and rifles in advance, the two leading divisions advanced towards the enemy, General Codrington’s brigade leading straight for the Russian intrenched battery. The two brigades of the 2nd division were separated by the burning village. The brigade of General Pennefather moved to the left of the village, close to the Sebastopol road, and found itself in the very focus towards which the Russians were directing their heaviest fire, both of artillery and musketry. Still undaunted, though suffering terrible loss, they pressed the Russians hard, and fully occupied their centre. While other operations were going on, the light division, under Sir George Brown, having moved across the plain in a long thin line, became somewhat broken among the vineyards and inequalities of the ground. As they approached, however, they found some shelter; and at length the word was given to charge. They sprang from their cover, and with a rattling fire rushed at the foe; and General Codrington’s brigade, 33rd and 23rd Regiments, and 7th Fusiliers, with the 19th on their left and the 95th on their right, were now in direct line, and in full view of the great Russian battery. The whole British line now opened a continuous fire—the Russian columns shook—men from the rear were seen to run; then whole columns would turn and fly, halting again and facing about at short intervals; but with artillery marching on their left flank, with Codrington’s brigade streaming upwards, and every moment pouring in their fire nearer and nearer as they rushed up the slope, the enemy’s troops could no longer maintain their ground, but fled disordered up the hill. The Russian batteries, however, still made a fearful havoc in the English ranks; and a wide street of dead and wounded, the whole way from the river upward, showed the terrific nature of the fight.

“Breathless, decimated, and much broken, the men of the centre regiments dashed over the intrenchment and into the great battery in time to capture two guns. But the trials of the light division were not over. The reserves of the enemy now moved down. The English regiments, their ranks in disarray and sorely thinned, were forced gradually to relinquish the point they had gained, and doggedly fell back, followed by the Russian columns. It seemed for a moment as if victory was still doubtful; but succour was close at hand. The three regiments of Guards (having the Highland brigade on their left) were now steadily advancing up the hill, in magnificent order. There was a slight delay until the regiments of Codrington’s brigade had passed through their ranks, during which time the struggle still wavered, and the casualties were very great; but when once their front was clear, the chance of the Russians was at an end, and their whole force retreated in confusion. The several batteries of the different divisions, after crossing at the bridge, moved rapidly to their front, and completed the victory by throwing in a very heavy fire, until the broken columns of the enemy were out of range. And now from rank to rank arose the shout of victory. Comrades shook hands, and warm congratulations passed from mouth to mouth that the day was won, and right nobly won. What recked then those gallant men of the toil, and thirst, and hunger, and wounds they had endured! Those heights on which at early morn the legions of Russia had proudly stood, confident of victory, had been gained, and the foe, broken and damaged, were in rapid retreat.”

In this fight the Royal Welsh Fusiliers especially distinguished themselves by their heroic valour; and no less than 210 officers and men, upwards of a quarter of their number, were killed or wounded during the battle. The brave young Lieutenant Anstruther carried the colours; and when he fell dead under the terrific fire from the chief redoubt, they were picked up by Private Evans, and by him given to Corporal Luby. From him they were claimed by the gallant Sergeant Luke O’Connor, who bore them onwards amid the shower of bullets, when one struck him, and he fell; but quickly recovering himself, and refusing to relinquish them, onward once more he carried them till the day was won, and he received the reward of his bravery, by the praises of his General on the field, and the promise of a commission in his regiment; and a better soldier does not exist than Captain O’Connor of the 23rd.

Captain Bell, of the same regiment, seeing the Russians about to withdraw one of their guns, sprang forward, and putting a pistol to the head of the driver, made him jump off, and springing into the saddle in his stead, galloped away with it to the rear, but was soon again at his post, and, all the officers above him having been killed or wounded, had the honour of bringing the regiment out of action. Colonel Chester and Captain Evans were both killed near the redoubt. Captain Donovan, of the 33rd, captured another gun; but the horses not being harnessed to it, the driver took to flight, and it could not be removed. Nineteen sergeants of that regiment were killed or wounded, chiefly in defence of their colours. The colours of the Scots Fusilier Guards were carried by Lieutenants Lindsay and Thistlethwayte. The staff was broken and the colours riddled, and many sergeants fell dead by their side, yet unharmed they cut their way through the foe, and bore them triumphantly up that path of death to the summit of the heights. The action lasted little more than two hours. In that time 25 British officers were killed, and 81 wounded; and of non-commissioned officers and men, 337 were killed, and 1550 were wounded. But death was not satiated, and many brave officers and men died from cholera even on the field of victory. One name must not be forgotten—that of the good and brave Dr Thompson, who, with his servant, remained on the field to attend to the wants of upwards of 200 Russians who had not been removed.

Lieutenant Lindsay, who carried the colours of the Scots Fusilier Guards, stood firmly by them, when, as they stormed the heights, their line was somewhat disordered, and by his energy greatly contributed to restore order. In this he was assisted by Sergeants Knox and McKechnie, and Private Reynolds. Sergeant Knox obtained a commission in the Rifle Brigade for his courage and coolness on this occasion.

(Continue to next chapter)

What a wasted chance for the Christian nations to ally together to free Constantinople from the Turks. Orthodox and Catholic should have burried the hatchet, turned their gaze south, and spread some freedom.

From a 21st century perspective, most of the 19th and 20th century wars between Occidental nations look like sheer fratricide.