Editor’s Note: The following comprises the twentieth chapter of Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1896). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER XX

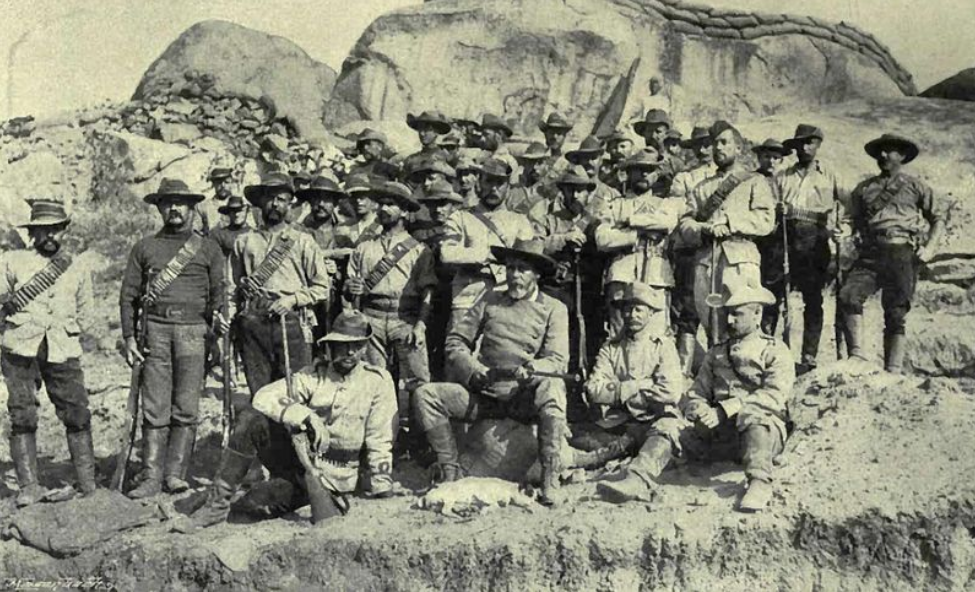

On our arrival in town we heard that the wire was down or had been cut by the natives between Bulawayo and Fig Tree Fort. A patrol was therefore at once organised to proceed along the telegraph line, repair the break, and then go on to Fig Tree in order to act as an escort back to town for a coach now due containing a large and valuable consignment of rifles. This patrol was under the command of Captain Mainwaring, and consisted of thirty-five men of his own troop of the Bulawayo Police Force, and twenty-two men of the Matabele Mounted Police under Inspector Southey.

Being due at Mabukitwani on Thursday evening, I left town early on the morning of that day, and joining Captain Mainwaring travelled with him down the telegraph line. We found the wire broken about three and a half miles from Bulawayo. One of the poles had been chopped down evidently with small-bladed native axes, whilst the wire itself had been cut and the insulator broken.

After the wire had been repaired we continued our journey, and reached the Khami river at about 2 P.M., where we remained till about seven o’clock. Then, both horses and men being rested and refreshed, we saddled-up and rode on to Mr. Dawe’s store, which is about half a mile from the old kraal of Mabukitwani. Here I heard that Lieutenant Grenfell had arrived with my troop from Matoli the same evening, and was encamped near the mule stable on the further side of the stream; so bidding good-bye to Captain Mainwaring, who decided to camp near the store, I at once rejoined my own men.

On the following morning Captain Mainwaring proceeded to Fig Tree, where he had not to wait long for the coach which he had come to meet, as he got back to my camp with it on Saturday evening. There were 123 rifles on board from which the locks and pins had been taken—each man of the escort carrying three of each—in order that, in the event of the coach being captured by an overwhelming force of Matabele, the rifles should be useless to them. However, both coach and escort reached Bulawayo safely, no rebels having been met with.

When about four miles from town they discovered the bodies of two white men lying on the roadside about 150 yards from their waggon. They had evidently been surprised by the rebels, and had made a bolt for life towards the road. The bodies had been terribly mutilated and hacked about, and seemed to have been lying where they were found for at least forty-eight hours. They were examined by Captain Mainwaring and Inspector Southey, as was also the waggon, but nothing was discovered by which to identify the murdered men except a branding iron. It was, however, subsequently ascertained that they were two Dutch transport riders named Potgieter and Fourie.

Strangely enough, these are the only white men who have been murdered on the main road from Bulawayo to Mafeking during the present insurrection, and it is noteworthy that they were not travelling along the road, but had been living for some time in their waggon some little distance away from it. I have no doubt that they were murdered by the party of rebels by whom the telegraph wire was cut on Wednesday, 22nd April. These men probably discovered their whereabouts the same evening, and were thus able to surprise and murder them during the night, or more probably at daylight on the following morning. The murderers were followers of Babian, one of the two envoys who visited England with Mr. E. A. Maund in 1899. The second envoy, Umsheti, is dead, or he, too, would be found in the ranks of the insurgents.

On Friday morning Lieutenant Grenfell and Mr. Norton rode into Bulawayo on business, and on the following day the former gentleman took part in the memorable fight with the Matabele on the Umguza, when for the first time the rebels were driven from their position in the immediate vicinity of the town, near Government House, which they have never since reoccupied.

During Mr. Grenfell’s absence, Messrs. Blöcker, Marquand, and myself chose a site for a fort on a kopje near the site of the old kraal of Mabukitwani, from the top of which a magnificent view of the surrounding country was obtainable, whilst with a certain amount of work the kopje itself could be turned into an impregnable fortress. Now that work has been accomplished, and Fort Marquand will long remain as a memento of the present struggle in Matabeleland. I christened it Fort Marquand, after my lieutenant of that name, whom, he being an architect by profession, I put in charge of the working parties, so that the fort was built entirely under his direction and superintendence, and whosoever may care to examine it will see for himself that it is a very good fort, built with great care and sagacity.

On Monday evening Lieutenant Grenfell and Mr. Norton returned to Mabukitwani, in company with a detachment of the Africander Corps which had been sent down under Commandant Barnard to meet Earl Grey, who was expected by the next coach. From Lieutenant Grenfell and Commandant Barnard and his men I heard all about the fight on the previous day at the Umguza, as they had all taken part in it. All agreed that the Kafirs had suffered very heavy loss, and been most signally discomfited, and Lieutenant Grenfell was kind enough to write for me the following account of the engagement:—

“On Friday, 24th of April, it was not difficult to discern that a determined move against the Kafirs on the Umguza was in contemplation. The situation was getting unbearable, the town being surrounded by the Matabele, and the operations against them with a view to clearing the country round Bulawayo not having hitherto been at all successful. In fact, an uncomfortable feeling was prevalent that we were in process of being closed in upon every side.

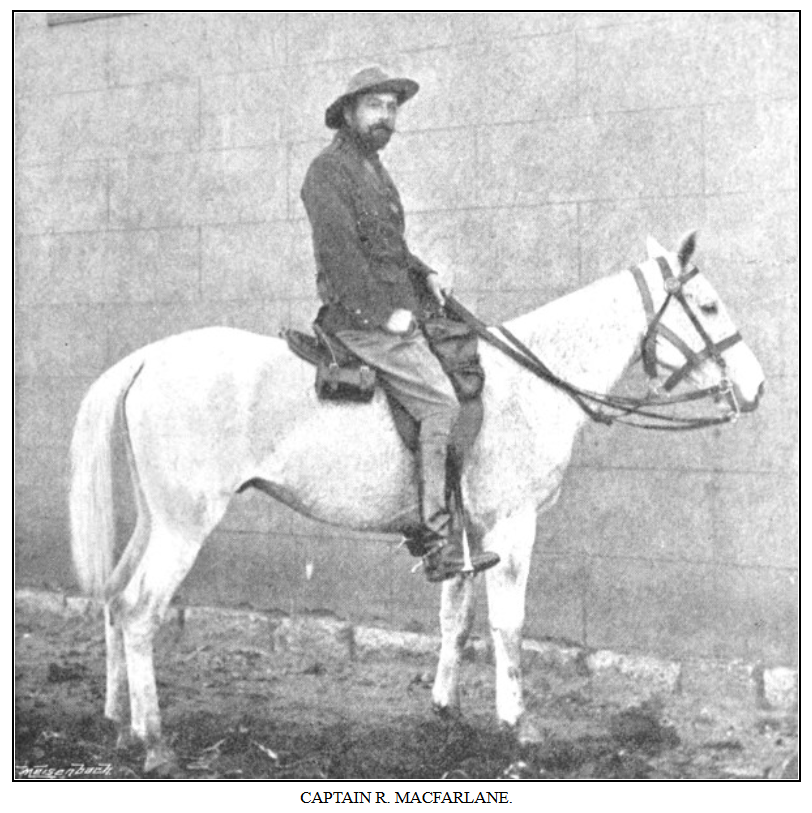

“It was therefore with great satisfaction that we learnt this Friday night that Captain Macfarlane was to be given as many men as could be spared, two guns, and a free hand, and go out in the morning. Great was the scrimmaging for horses among the unattached, unexpectedly sudden the popularity of the remount officer. There is a good deal to be said in favour of fighting when the state of affairs is such that you can go out after morning coffee to a certain find, with every chance of a gallop and a kill, and return to a late breakfast at say 2 P.M. There were rumours, too, that this time we really meant business, and that the natives would be encouraged to surround us on all sides, in order to give every opportunity to the machine guns and rifle fire.

“Such were the directions actually given by Captain Macfarlane to his officers, when on the march, and the tactics proved to be sound enough. The patrol consisted of 35 Grey’s Scouts under Captain Grey; 25 B troop under Captain Fynn; 15 of Captain Dawson’s troop; 35 of the Africander Corps under Commandant Van Rensburg; 100 Colenbrander’s Cape Boys under Captain Cardigan, and 60 to 70 Friendlies under Chief Native Commissioner Taylor; 1 Hotchkiss and 1 Maxim under Captain Rixon, and an ambulance with stretchers under Dr. Vigne; making in all some 120 whites and about 170 Colonial Boys and Friendlies all told, all under the command of Captain Macfarlane. Mr. Duncan, Colonel Spreckley, Captain Nicholson, Town Major Scott, Captain Wrey, and several other unattached officers and scouts, also accompanied the force. It is worth mentioning that Messrs. F. G. Hammond, Stewart, Anderson, Farquhar jr., and two or three more, shouldered their rifles and marched out on foot, in order to participate in the day’s work.

“The patrol left Bulawayo at 7.30 in the morning of the 25th of April, and proceeded in a north-easterly direction, taking the road to the right of the scene of the recent engagements on the Umguza river. The Scouts went on ahead as usual, the Africanders opening out on the left, and Captain Dawson taking command of the right flanking party, the guns bringing up the rear with an ambulance waggon and the Friendlies. This order was kept until a small bare eminence was reached on which stood four old walls, the wreck of a small farmhouse some three miles out of Bulawayo. There was a circuit of bush in front of this position, then the Umguza river, and beyond that rocky ground with thick bush rising from the river, the lines of the native “scherms” showing up black on the heights in the distance.

“Up to now nothing had been seen of the enemy, only some smoke from their fires. The Scouts rode down to the river with orders to draw the enemy on, while the rest of the men took up their places round the two guns. The position was very suitable for both the Maxim and the Hotchkiss; but afforded absolutely no cover for the men. The rebels, several hundred in number, no sooner saw the Scouts than they streamed down to the river, shouting out a loud challenge to come on, which was answered by our side. The Scouts drew back slowly, bringing the Kafirs well on, but were finally driven in on our position with a rush, and the Kafirs pulled up about 200 yards off in the bush, firing very rapidly. Bullets of all sorts came whistling along, from elephant-guns, Martinis, Winchesters, and Lee-Metfords, and for about an hour things were decidedly unpleasant, though up to this time we had only one man killed and one wounded. Our firing was incessant, and the shooting, though mostly at long range, very steady, and as effective probably as our exposed position and the cover afforded our assailants by the bush would allow. After the rebels had made two determined efforts to approach the Maxim, in both of which they were foiled, their fire slackened, and they apparently sent their best marksmen to the front to see what they could do.

“At this juncture, however, Captain Macfarlane ordered the Africanders to charge those on our left, and the brilliant manner in which this was carried out will not soon be forgotten by those who witnessed it. The enemy had cover here behind some rocky ridges, but the Africanders rode them out of this ground in the cheeriest way possible—they use rather more “noise” fighting than the Britishers do—and sent them flying over the river, killing no fewer than seventy-four at the crossing, and completely breaking up that wing of the enemy’s line. The Hotchkiss planted several shells very well among the flying natives; whilst on our side only one horse was lost in the charge.

“About this time the Scouts were ordered to drive off the rebels to our front, and in this they succeeded admirably, but owing to the bad ground they had three men wounded. Lovett was shot here, and subsequently died from the effects of his wound, whilst John Grootboom, a very plucky colonial native, well known in Rhodesia, was also hit in two places while trying to drive some natives out of a donga.

“Meanwhile Captain Dawson with his men on the right had been holding his own under a galling fire in open ground, unable to have a good shot at the enemy who were in the bush. They were having a very warm time of it, and had lost two men killed and one wounded, when Burnham was ordered to clear the bush with 100 of the Taylor’s Friendlies, wearing red capes and carrying assegais. The charge was successful, and, backed up by Captain Taylor and Colenbrander’s Cape Boys armed with rifles, the Friendlies cleared the bush and relieved Dawson from the hidden enemy.

“About this time a message arrived from Captain Colenbrander that a fresh impi from the west meant to attack us, and sure enough they turned up very soon after, but seeing how the others had fared they kept fully half a mile off, sending a number of shots after the Africanders, whom they tried to cut off. The Maxim and Hotchkiss, however, kept them from coming nearer. The main body of the enemy having now partially reformed, the Africanders went to assist the Scouts, and the enemy were driven off fully two miles, one of our men and one horse being wounded in the sortie.

“Captain Macfarlane thought it was now time to get home, as the wounded would take some time to see to, and there was a chance of his having to fight his way back to town; so orders were given for the ambulance to prepare to return to Bulawayo, and the whole column marched back in good order, having had by far the most successful day since the commencement of the rebellion. Our loss was four white men killed and four wounded, two Cape Boys and one Friendly wounded, one horse and one mule killed. It is very difficult to estimate the number of natives engaged, but there were probably at least as many as 2000 in all opposed to us. How many were killed it is difficult to say, but from the bodies which were counted, and from the reports of the wounded brought in by Captain Colenbrander and his boys, who were over the ground in the afternoon, the enemy’s loss must have been considerable. A vidette party of four mounted men, who were sent out to Government House in the morning, allowed themselves to be surprised and surrounded by the rebels, and one, unfortunately, got killed, namely Trooper B. Parsons of D troop, the other three just escaping with their lives.

“After the return of the column in the afternoon from the Umguza, a small patrol under Lieutenant Boggie, consisting of thirty dismounted men of C troop, fifty of Colenbrander’s Cape Boys, and ten of Grey’s Scouts mounted, with one Maxim gun, went out in the direction of Sauer’s house, and turning to the left, past Government House and Gifford’s house, picked up Trooper Parsons’ body, and returned to town via the Brickfields, not having seen any of the enemy. A seven-pounder was placed in position on the rise at the back of Williams’ buildings, trained ready on to the ridge at the left of Government House, in order to shell the position if necessary. After the return of the patrol the Observatory reported the appearance of a large body of the rebels, who came over the ridge to the east of Government House down as far as the spruit. Trooper Edward Appleyard, seriously wounded on the Umguza in the morning, died on Saturday night, and at 11.30 on Sunday morning his body, together with those of Troopers Whitehouse, Gordon, and Parsons, was accorded a military funeral.”