Editor’s Note: The following comprises the ninth chapter of Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1896). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER IX

When on the afternoon of Thursday, 26th March, we got back to my homestead with the recaptured cattle, both men and horses were tired out, as the heat had been intense, and the former had had no food since early dawn. However, the cart carrying provisions having arrived, the men were soon able to get a good meal, whilst the horses were turned into a twenty-five acre patch of maize, which, although it had been sadly destroyed as a crop by the locusts, still afforded an abundance of sweet succulent food for stock. In order to allow the horses time to recover from the effects of their hard day’s work in the hills, I resolved to let them feed and rest until the cool of the afternoon of the following day, and then make a night march over to Mr. Jackson’s police station at Makupikupeni, where I hoped to be able to get some news as to the whereabouts of Colonel Spreckley’s patrol, with which I was anxious to effect a junction. I should have sent the recaptured cattle at once in to Bulawayo, had it not been for the rinderpest scourge which would have rendered such a course worse than useless, since every one of them would have died within a week. The only other plan open to me was to commit them to the care of the natives living immediately round my homestead, who, at this time at any rate, did not seem at all inclined to take part in the rebellion.

As there were now at least 500 head of cattle collected together in a small area, I fully recognised the danger there would be lest so rich a bait should attract a Matabele raiding party as soon as it became known that there was no one left to defend them. However, no other course was open to me, so the cattle were left on the off chance that they would not fall into the hands of the rebels.

Some ten days later the not unexpected came to pass. Inxnozan, an old Matabele warrior, whom I knew well, and whose manly independent bearing I had always admired, descended upon my homestead with a following of some 300 men, burnt down my house and stables and all adjoining storehouses and huts, and either carried off or destroyed everything they contained. Then they collected all the cattle in the neighbourhood, all of which belonged to my Company by right of purchase or capture, and went off. All the Kafirs who up to this time had been living quietly in their kraals looking after my cattle went away into the hills after Inxnozan’s visit, and as they have never sent me any message, I do not know whether they have joined the rebels or have only taken refuge in the hills until the war is over. At any rate I shall do all I can to protect them, as they must have been placed in a very difficult position—fearing the enmity of the rebels on the one hand, if they refused to join them, and the vengeance of the white man on the other for suspected complicity in some of the outrages that had taken place in the district if they remained at their kraals.

On the Friday afternoon we made a start for Mr. Jackson’s police station, passing the remains of the once large military kraal of Intuntini, and still the largest in the district. Such as it was, we set it alight, and as it was situated on the shoulder of a hill the burning huts must have been plainly visible to the people who had so lately deserted it, from almost any point in the Malungwani range, to which they had probably retired.

Shortly after midnight we reached the police station, which we found entirely deserted, though all the huts were still standing. A closer inspection showed that these huts had been very hastily evacuated by the native police to whom they had belonged, as they were still full of their personal effects, such as coats, hats, blankets, etc. In one of the huts we found a broken Winchester rifle, and in one of the coats a purse containing a few shillings in silver, about the last thing a Kafir would willingly leave behind him. We afterwards learned that Colonel Spreckley’s patrol had reached the police station—which was situated on the main road to the Filibusi district from Bulawayo—late at night on the previous Wednesday. At this time there were seven native policemen with a sergeant in the huts. These men, hearing the horsemen approaching, immediately fled, taking nothing with them but their arms and ammunition, and went over to the rebels. That they must have previously made up their minds to desert, is, I think, certain, otherwise there was no reason why they should have left the station of which they were in charge on the approach of the white men. In one of the huts we found several bags of maize, and so were able to give all our horses a good feed.

On the following morning I paid a visit to several kraals in the neighbourhood, the inhabitants of which were in charge of cattle belonging to my Company. These people I found in their villages. They were subsequently attacked by the rebels, who carried off a large proportion of the cattle in their charge. They however escaped with the remainder, which they brought in to Bulawayo, where they very soon all died of rinderpest. These Kafirs are amongst the few who out of the entire nation have stood by the Government and rendered active assistance to the white men during the present crisis. They are Matabele Maholi of Makalaka descent, as I think are all the “friendlies,” with the exception of a small leavening amongst them of “Abenzantsi” or Matabele of pure Zulu blood, and I think I am correct in stating that there is not a single Maholi of any other descent who is not in arms with the pure-blooded Matabele against the Government.

The Makalaka proper, a numerous people living on the western border of Matabeleland, have—except possibly with some individual exceptions—held themselves resolutely aloof from any participation in the present rebellion, just as they took no part in the war of 1893. They are an industrious, peaceable people, and have found the rule of the Chartered Company if not perfect, at any rate a vast improvement on the oppressive tyranny under which they lived in the good old days of Lo Bengula.

At Makupikupeni we heard a rumour, which happily proved to be entirely false, though at the time it disturbed my peace of mind very much, to the effect that the ninety native police who had accompanied Mr. Jackson and his companions into the Matopo Hills, on the trail of Umzobo and Umfondisi, had mutinied and murdered their officers, Mr. Jackson having been bound to a tree, and then having had his throat cut. We also heard that Colonel Spreckley had buried the white men who were murdered at Edkins’ store, and then crossed over to the Tuli road and returned to Bulawayo.

This being so, I determined to make for Spiro’s store, situated just on the edge of the Matopo Hills on the main road from Bulawayo to the Transvaal, and about twelve miles distant from the Makupikupeni police station, as I was in hopes of there hearing something authentic concerning the fate of my friend Mr. Jackson and his companions. I knew the way across country to the store well enough myself, but had I not done so, I had a good guide with me in the person of one Mazhlabanyan, a Matabele—not of Zulu blood, but of Makalaka descent—who had joined me that morning. This man had known me in former years when he was an elephant-hunter in the employ of the late Mr. Thomas, and on hearing that I was residing on Essexvale, had come with his wives and family to live near me, and I had given him a nice little herd of cattle—amongst them some good milk cows—to look after for our Company, for which he was very grateful. He fought in the war of 1893 against the whites and was with the Imbezu at the battle of the Impembisi, on which occasion he was the recipient of a bullet through the shoulder.

During the present troubles, however, he has stood by the Government, and joined the rest of the “friendlies.” Shortly before sundown we reached Spiro’s store, which we found had been deserted by its occupants not many hours prior to our arrival. The colonial boys in charge of the coach mules were still at their post, and reported everything quiet in the district as far as they knew, nor could they give any information concerning Mr. Jackson.

Since mid-day the weather, which had been intensely dry and hot for some time past, had changed suddenly, the sky became overcast and a light rain commenced to fall. Luckily, however, there proved to be sufficient accommodation in the out-buildings and beneath the broad verandah which surrounded the store for all my men, and we were thus spared the disagreeable necessity of sleeping out on the wet ground and beneath a rainy sky.

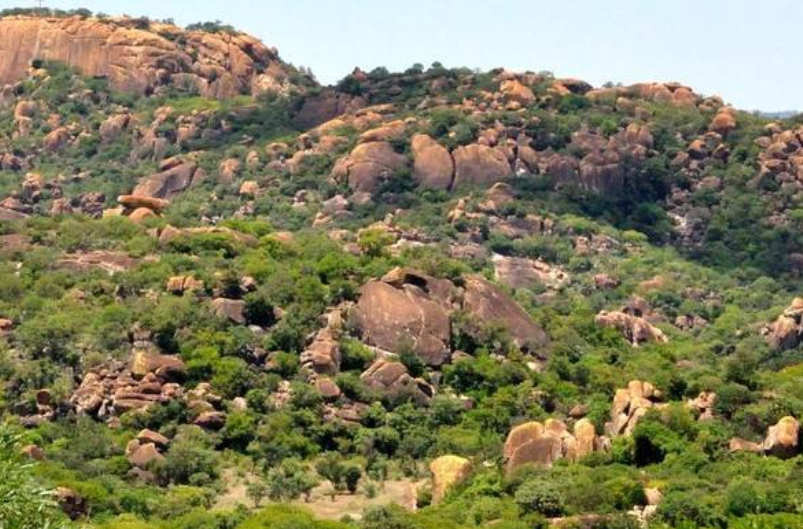

The next day—Sunday, 29th March—broke fine, but cool and cloudy, a very pleasant change after the excessive heat we had recently experienced. The question now arose as to whether any other course was open to me but to return at once to Bulawayo by the Tuli road. To my left lay the rugged mass of broken granite hills called the Matopos, within whose recesses it was believed by many people at Bulawayo that the Matabele had already massed in large numbers. Now I fully realised that had this been the case, it would have been madness to take so small a force as that at my disposal into so difficult a country. As, however, I had very good reasons for believing that as yet no large number of Matabele had assembled in this part of the country, I was anxious to make a reconnaissance through them in order to see what the difficulties of the country really were.

Before starting I paraded my men and told them what I wished to do, stating that in my opinion, although we should have some very rough country to get over, and should have to walk and lead our horses most of the way, we should not meet any large force of hostile Kafirs, or indeed be likely to fire a shot at all unless we met some of the revolted police who had murdered Jackson—for at this time I believed that he had really been murdered. However, I told them that I did not wish any one to go with me who did not care to do so, which was unnecessary, as no one was willing to be left behind.