Editor’s Note: The following comprises the seventh chapter of Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1896). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER VII

In spite of their submissive behaviour, it seems probable that all the members of the late king’s family and many of the chief Indunas were only biding their time, and waiting for an opportunity to try the chances of a rebellion against the white man.

This opportunity did not present itself as long as there was a strong police force in the country, but once that police force was removed, I think the malcontents began to act.

That the plague of locusts with which Matabeleland has been afflicted ever since 1890, the first year of the occupation of Mashunaland by Europeans; the partial drought of the last two years; and, finally, the outbreak of the rinderpest, would all be ascribed to the evil influence of the white man, and made use of by the witch-doctors to incite the mass of the people to join the insurgents, is doubtless true; but that the insurrection can be fairly ascribed to the bitterness caused by these visitations alone, I very much doubt, for it is remarkable that throughout the Umzingwani, Filibusi, and Insiza districts, where all the first murders of white men were committed, the rainfall had been plentiful, and the locusts had done but little damage, so that, as I can personally bear witness, the crops throughout these portions of the country were exceptionally good, whilst as the rinderpest had not yet approached this part of Matabeleland, the people living in these districts could have known little or nothing about it. In its inception, the insurrection was, in my opinion, a rebellion against the white man’s rule by the Matabele of Zulu origin alone, and I am convinced that, in the district where I was living at least, the other section of the tribe were at first not in the secret; however, the greater part of these soon joined, some unwillingly and under threats from their former masters, but most of them readily enough, believing, as they did, that with the assistance of the Umlimo they would be able to completely root out the white man, and revel once more in loot and wholesale murder. And a merry time they had of it, if it was but a short one, to be followed by a heavy retribution.

When the first news of the rising reached Bulawayo, Gambo was in the town on a visit to the chief native commissioner, by whom he was very wisely detained as a prisoner. Whether, if he had been at large, he would have joined the rebels or not, it is difficult to say. Since the war, he has lost control over the greater part of the people who formerly composed the Eegapa military division, and many of these have joined the ranks of the insurgents, but all Gambo’s own people, under his head Induna, Marzwe, have remained loyal to the Government. Umjan, once the Induna of the Imbezu regiment, and now quite an old man, has also refrained from taking part in the present hostilities, although he is one of the few whose cattle were shot by order of the Government because they were infected with the rinderpest. He came in to Bulawayo soon after the outbreak of the rebellion with his wives and immediate attendants, and is now living quietly near the town. His sons, however, have joined the rebels, whilst the men whom he formerly commanded—the Imbezu—reformed themselves into a regiment, and have been fighting since the outbreak of the insurrection.

Besides Gambo’s men, a few hundreds of Matabele Maholi (men of Makalaka and Mashuna descent) living on my Company’s property of Essexvale, on Colonel Napier’s land and round the Hope Fountain mission station, have thought it advisable to stand by the Government, and have, therefore, come in to live near Bulawayo for protection. But putting aside these few hundreds of natives who have not joined in the rebellion, the fact remains that at least nine-tenths, I think I might safely say nineteen-twentieths, of the Matabele nation are now in arms against the whites.

And, now, let us see how the colonists were prepared to meet the onset of these hordes of savages. When the rising first broke out, with the exception of the native police, there was no organised force in Matabeleland worth speaking of; and as one-half of the native police at once went over to the enemy, and the remainder had to be disarmed, for fear lest they should follow suit, it may be said that there was no police force at all. Of the old Mounted Police there only remained forty-eight officers, non-commissioned officers, and men, in the whole of Matabeleland, under Inspector Southey. Of these, twenty-two were stationed in Bulawayo, and the rest distributed over the country at the police stations of Gwelo, Selukwe, Belingwe, Inyati, Mangwe, Tuli, Matopos, Umzingwani, and Iron Mine Hill. When the rebellion broke out only twelve of these men were available at Bulawayo for immediate service, and these, under Inspector Southey, accompanied Mr. Gifford to the Insiza. The Rhodesia Horse, a volunteer force which had been raised and equipped the previous year, had also practically ceased to exist as an effective force fit for use at a moment’s notice, for although there were some six hundred men in Matabeleland who had enrolled themselves as members of this corps, they were scattered all over the country at the outbreak of the rebellion. Some of these were murdered, whilst others had to take refuge in the laagers of Belingwe and Gwelo. However, about five hundred were soon mustered in Bulawayo, but the services of the majority could not be utilised except to defend the town, owing to the want of horses, since, so great had been the ravages of the fatal horse-sickness during the rainy season then just coming to an end, that when Colonel Napier, the senior officer of the Rhodesia Horse, called on the Government for seventy horses for immediate use on 23rd March, he could only be supplied with sixty-two.

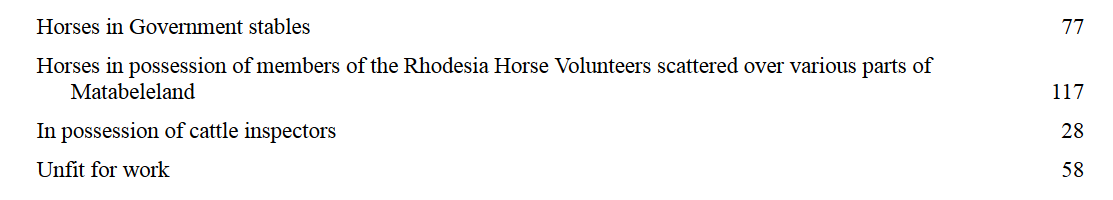

The actual number of horses in the possession of the Government throughout Matabeleland on the day when the first tidings of the outbreak of the insurrection reached Bulawayo is as follows:—

Of the 117 horses that had been issued to Volunteers, a good many never returned to Bulawayo, as they either died of horse-sickness or were taken to Gwelo or Belingwe, so that in the first days of the rebellion the Government could not command the services of more than 100 horses; but no expense was spared to procure more, and very soon all the private horses in Bulawayo were bought up, whilst others were sent up from the Transvaal, so that by the end of April there were nearly 450 horses in the Government stables, the large majority of which were fit for active service.

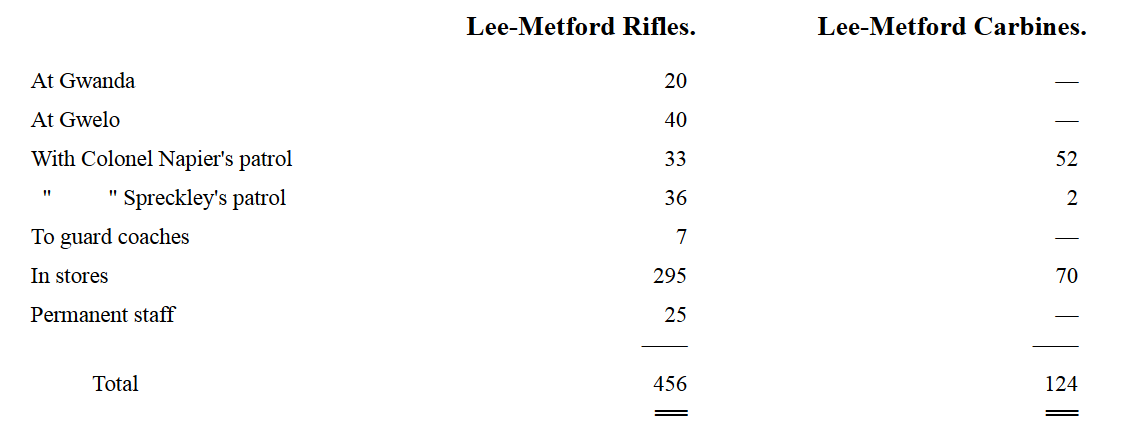

The number of rifles belonging to the Government throughout the country on 25th March was as follows:—

Making a total of 580 rifles all told.

Besides these, however, there were about eighty old Martini-Henry rifles in the Government stores, but these were nearly all unserviceable at the outbreak of the rebellion, though the armourer has since been able to get most of them into working order. Of ammunition there was a good supply, viz. 1,500,000 rounds.

In the way of artillery there was in Bulawayo when the insurrection broke out one 303 Maxim gun in good order, and a second so much out of repair as to be useless; two 2.5 screw guns in good order, but with only seventeen rounds of ammunition for the two; one Hotchkiss gun and limber, one Gatling, one Gardner, one Nordenfeldt—all in good order—and one seven-pounder, useless except at Bulawayo owing to carriage having been destroyed by white ants. In addition to this ordnance there arrived in Bulawayo from Macloutsie, on the very day on which Mr. Maddocks was murdered, two old Maxims and two seven-pounders. These, however, were unserviceable at the time, one of the seven-pounders being without a carriage and the two Maxims being also out of repair. The armourer here has now, however, I believe, put them all in working order.

Taking these figures as correct—and they are absolutely beyond question—it cannot, I think, be said that the colonists in Matabeleland were very well prepared to cope with a sudden and unexpected rising of at least 10,000 natives, about one-fifth of whom were armed with breech-loading rifles and well supplied with ammunition, whilst many more were in possession of muzzle-loading guns; and when it is remembered that at the time of the outbreak the food supply was very low in Bulawayo, owing to the ravages of the rinderpest, it must be acknowledged that the position was at one time a very serious one, which a little more intelligence on the part of the Matabele might have rendered absolutely disastrous.

But all through they have behaved in an incomprehensible manner, their leaders apparently never having arranged any settled plan of campaign, the consequence being that there has never been any understanding or community of action between the various hordes into which the nation is now divided. All through there appears to have been a general belief amongst them that they would receive supernatural aid from the “Umlimo,” or god, but this belief must be getting a little thin now, and they would have done far better had they worked together under one intelligent general.

Why, when the rebellion first broke out, they never attempted to block the main road to Mangwe will ever remain a mystery. No one doubts that they might have done so, nor that, if they had placed a couple of thousand men in the Shashani Pass, we could not have raised a sufficient force on this side to dislodge them and open the road; for it must be remembered that as there were over six hundred women and children in Bulawayo a large force was always necessary to protect them. Possibly there is some truth in the report that the road to Mangwe has been purposely left open by command of the Umlimo in order to give the white men the opportunity of escaping from the country. That this was an error of judgment, if it is a fact, is very clear, as in the critical time but few men left the country, and such as did could be well spared, as they were of no use as defenders of the women and children, and were only consuming valuable food. On the other hand, owing to the road having been left open, stores of arms and food and horses were constantly being brought in.

It certainly seems very strange that no attempt has ever been made to stop waggons and coaches on this road, when it is remembered that at one time Government House—which is less than three miles from the centre of Bulawayo—was practically in the hands of the rebels, sometimes in the daytime and always at nights for a period of about ten days, their impis during that time lying in a semicircle to the west and north of the town, and being sometimes within two miles of it.

Yet although two Dutchmen, living in their waggon standing near the boundary of the town commonage, about four and a half miles along the road from Bulawayo, were murdered, no waggon or coach moving along the road was ever interfered with, nor was the Government House burnt, the reason for this being, it is said, because the Umlimo told the people that when Bulawayo had been destroyed, and all the white men in the country killed, they would find Lo Bengula sitting there, ready to rule them once more; for, be it said, Government House has been built in the centre of the old kraal of Bulawayo, just where the king’s house once stood.

For over a month, an impi, supposed to be at least a thousand strong, was camped just within the Matopo Hills, not ten miles from the nearest point on the road to Mangwe, and no one doubts that at any moment a portion of this impi might have moved over to the road by night, and, by shooting a mule or two, have had a coachload of white men at its mercy; and God help the unfortunate white man who has nothing else to trust to but the mercy of the Matabele!

Of course there were forts along the road, and patrols rode daily between the forts, but even so I maintain that much damage might have been done if the natives had determined at any moment to block the road. Now, however, that the impi of which I have been speaking has been driven from its position by the forces under Major-General Sir Frederick Carrington, it is not likely that the safety of the road will ever again be threatened.

And, now, let me hark back to the early days of the rebellion. I think I have shown by figures that on the outbreak of the insurrection the country was not over well supplied with either horses or arms, nor was there any superfluity of men, and the smallness of the number will, I think, astonish some critics of the present campaign in England. Turning to the Matabele Times of 6th April last, I find it stated under the heading “The Native Rising up to Date,” “A census was taken of all those who had been in the laager on Friday night as they made their exit on Saturday morning, or remained on the waggons. The count was carefully made, and showed that the refugees numbered 632 women and children, and 915 men, making a total of 1547″; and further on we read—”A general parade was held yesterday of the men now in town who have enrolled themselves in the Bulawayo Field Force. They fell in at ten o’clock, the scouts, under Captain Grey, in front making a splendid display of the class of men whom the hostile natives will not seek to tackle twice. The men on foot looked like business, and went through their movements with sufficient precision. The Africander Corps now consists of three companies, numbering 76, 64, and 73, with 6 on the staff. The total number on parade was over 500, of whom about 300 were fully armed, and about 100 were engineers and artillerymen. To this number have to be added the 169 out under the Hon. M. Gifford and Captain Dawson, and the 100 men gone down to Gwanda under Captain Brand and Captain Van Niekerk. The total efficient force now available for the reconquest of Matabeleland may be put down at 700, nearer 800.”

From these figures it will be seen that at the outbreak of the rebellion there were under 1000 men in Bulawayo, some 200 of whom were unfit for active service. The remainder of the male population of the country were shut up in the laagers at Gwelo, Belingwe, and Mangwe, and therefore unavailable for offensive operations against the Matabele; whilst of the 800 fighting men in Bulawayo, it was necessary to have at least 400 always in town to protect the women and children, and 130 were drafted off to man the forts on the Mangwe road, leaving less than 300 available for active operations against the enemy. This force was, however, augmented by about 150 Cape boys, chiefly Amaxosa Kafirs and Zulus. These boys were got together and formed into a regiment by Mr. Johan Colenbrander, and they have done most excellent service during the present campaign, being man for man both braver and better armed than the Matabele.

Thus, all things considered, I do not think the colonists have done so badly. With small patrols they first succeeded in bringing in many scattered whites from the outlying districts, and then after a series of engagements, always fought on ground of the enemy’s own choosing, succeeded in driving them from the immediate neighbourhood of Bulawayo, and forcing them to take refuge in the forests and hills, from which they will be finally driven by the forces now in the country under the command of Major-General Sir Frederick Carrington.

It is worthy of remark that whilst in the first war the Matabele attacked strong positions defended by artillery and Maxim guns, thereby suffering very heavy loss themselves but killing very few white men, in the present war all the fighting has been amongst broken ground, and in country more or less covered with bush, and all the killing has been done with rifles; for in the first war the natives learnt the futility of attacking fortified positions, and now only fight in the bush in skirmishing order, giving but little opportunity for the effective use of machine guns; so that, although a good many rounds have been fired from Maxims at long ranges, only a very small amount of execution has been done by them.